chapter 4: institutional values and perspectives

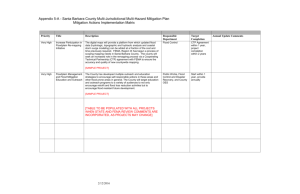

advertisement