liu-chinese-char - Virginia Review of Asian Studies

advertisement

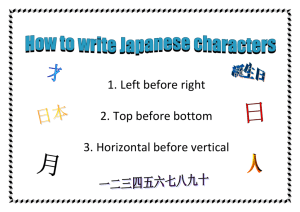

160 CHINESE CHARACTERS THROUGH SIMPLIFICATION AS A JAPANESE STRATEGY XUEXIN LIU SPELMAN COLLEGE Introduction: Beyond linguistic borrowing1 ‘Linguistic borrowing’ is generally defined as transference of linguistic elements from one language into another, and it has been recognized as a universal linguistic phenomenon. Whenever a speech community incorporates some linguistic element into its contemporary language, linguistic borrowing occurs. Such a phenomenon has been long studied by scholars in various fields of linguistics, such as sociolinguistics, contact linguistics, anthropological linguistics and historical linguistics (e.g., Haugen 1972; Weinreich 1979; Poplack, Sankoff & Miller 1988). As most frequently observed in all studies of linguistic borrowing, linguistic transferences are most common in the realm of vocabulary, and this type of borrowing is specifically referred to as ‘lexical borrowing’.2 As the term suggests, the borrowing language may incorporate some cultural item or idea and the name with it from some external source, that is, from some other language, to meet its lexical-conceptual needs. As a linguistic principle, when lexical items are borrowed, they are generally made to conform to the existing structural configurations of the borrowing language, including phonological structure, morphological structure, syntactic structure, and semantic structure. In addition to sociolinguistic and sociocultural motivations for lexical borrowing, one of the most significant findings of the previous studies is that lexical borrowing is one of the primary forces behind changes in the lexicon of many languages (cf. Romaine 1995; Myers-Scotton 2002). Although there have been numerous studies of lexical borrowing involving various borrowing languages and source languages, there have been few studies which have investigated and explored the idiosyncratic nature of Japanese3 in relation to its borrowing of Chinese characters. This paper specifically describes and explains the effects of Chinese characters borrowed into Japanese through some necessary morphological change (i.e., change in word form) and semantic shift or modification (i.e., change in word meaning). In order to do so, it introduces a comparative study of simplification of Chinese characters in Japan and China with a focus on the Japanese linguistic and sociolinguistic motivations for such a particular linguistic strategy.4 Accordingly, this paper discusses several specific questions: What makes Japanese lexical borrowing of Chinese characters different from the traditional notion of lexical borrowing? What are the particular motivations for simplifying Chinese characters in Japan and China? What are the orthographic effects of simplified traditional Chinese characters in contemporary Japanese? What are the most important implications of the Japanese simplification of Chinese characters for understanding linguistic borrowing in general and lexical borrowing in particular? To answer these questions, some representative orthographic records are cited as 161 linguistic evidence, the findings and assumptions through the comparative study will be presented, and some tentative implications will be offered. As also observed, some Chinese characters once borrowed into the Japanese language (i.e., Japanese kanji) show some semantic shift or semantic change (i.e., certain borrowed Chinese characters no longer contain their original lexical content as in Chinese but carry different meaning).5 This becomes an issue of the relationship between lexical borrowing and semantic shift or semantic change. In addition, a few wasei kanji/kokuji, such as 峠、働、榊、 畑、and 辻, though they look like Chinese characters, were actually made in Japan. Furthermore, since Meiji period, many Japanese kango were created through word combination, such as 衛星、 科学、銀行、弁当、寿司、人気、写真、and 物語 or through translation of Western documents to fit its culture and modernization needs, and such newly formulated phrases now appear in Chinese as its recently borrowed lexical items (cf. Chen 1999; Zhou 2003). Such linguistic phenomena involving lexical borrowing, lexical shift or creation, and new word formation need to be explored and described systematically; however, these topics are beyond the scope of the main interest and focus of this paper. Kanji as a component of the Japanese linguistic system Different from most languages in the world, Japanese has its own peculiar componential linguistic system, and different from most types of and motivations for linguistic borrowing, Japanese borrows linguistic elements from other languages for its special reasons. All this is determined by the componential nature of the Japanese language itself. Japanese consists of three distinctive but related components: hiragana, katakana, and kanji, each of which plays its special role in the Japanese linguistic system (cf. Kindaichi 1978; Nakama 2000; Yokoso 1998). Let us take a brief look at each of these components and its role in structuring the Japanese language. Hiragana is a Japanese syllabary, one of the components of the Japanese writing system. Along with the other two components, katakana and kanji, hiragana has its own particular forms and functions. Hiragana are used for words for which there are no kanji, including particles such as kara ‘from’ and suffixes such as ~san ‘Mr., Mrs., Miss, Ms.’ Hiragana are also used for Japanese inflectional morphology, such as verb and adjective inflections. For example, in tabemashita (食べました‘ate’), BE MA SHI TA (called okurigana) are written in hiragana. In this case, part of the root is also written in hiragana. In addition, hiragana are used in words for which their kanji form is not known to the writer, is not expected to be known to the reader or is too formal for the writing purpose. Furthermore, hiragana are used to give the pronunciation of kanji in a reading aid called furigana. For example, 日本語 ‘Japanese language’ is given ‘にほ んご’ as the reading aid (cf. Makino, Hasata & Hasata 1998; Tohsaku 1994). Katakana is also a Japanese syllabary, another component of the Japanese writing system along with hiragana and kanji, and in some cases the Latin alphabet. The word ‘katakana’ means ‘fragmentary kana’, as they are derived from components of more complex kanji. In modern Japanese, katakana are most often used for transcription of borrowed lexical items from foreign languages, called gairaigo (cf. Makino, Hasata & Hasata 1998; Tohsaku 1994). For example, 162 ‘television’ is written テレビ. In a similar way, katakana are usually used in writing country names, foreign places, and personal names. For example, ‘Canada’ is written カナダ, ‘Atlanta’ is アトランタ, and ‘John’ is written ジョン. In addition, katakana are used for technical and scientific terms, proper names, loanwords, and so on. Katakana are also used instead of hiragana to give the pronunciation of a word written in Roman characters, or for a foreign word, which is written as kanji for the meaning, but intended to be pronounced as the original. It is very common to write words with difficult-to-read kanji in katakana in modern Japanese. To put it simple, katakana are used mainly for all such transcription purposes. Kanji,6 which literally means ‘Han characters’, are the Chinese characters that are used in the modern Japanese logographic writing system along with hiragana, katakana, and the Arabic numerals. Unlike the most commonly observed phenomena of lexical borrowing, Chinese characters were actually ‘introduced’ to Japan. Classical Chinese characters first came to Japan on articles imported from China. One instance of such an import was a gold seal given by the emperor of the Eastern Han Dynasty in 57 AD. At the time the Japanese language itself had no written form. It has not been documented when Japanese people started to command Classical Chinese by themselves. What is known is that approximately from the 6th century onwards, Chinese documents written in Japan tended to show interferences from Japanese. This suggests the wide acceptance of Chinese characters in Japan (cf. Makino, Hasata & Hasata 1998; Tohsaku 1994). In modern Japanese, kanji has become a significant component of the Japanese linguistic system. While kanji are essentially Chinese hanzi used to write Japanese, they have gone through some significant Japanese local developments, including difference between kanji and hanzi, the use of characters created in Japan, characters that have been given different meanings in Japanese, and post World War II simplifications of the kanji.7 It should be clear that the three components of the Japanese language are distinctive but related, each of which plays its designated role in the Japanese writing system. While hiragana are used to write inflected verb and adjective endings, particles, native Japanese words, and words where the kanji is too difficult to read or remember; katakana are used for most if not all foreign loanwords; kanji are used to write parts of the language such as nouns, adjective stems and verb stems. Different from the traditional notion of lexical borrowing, Chinese characters ‘borrowed’ into Japanese are not simply for the so-called lexical-conceptual purpose but for the linguistic needs of the Japanese language itself. In other words, Chinese characters, whether they have gone through Japanese local developments or not, have become a fundamental component of the language (Seeley 1995). Motivations for simplifying Chinese characters in Japan and China Any language reform in any society is driven by particular motivations of a speech community, and such motivations may be linguistic, social, cultural or educational. There must be various factors involved in any language reform. One of the most important factors must be the government’s language policy and planning. It is in this sense that we say all language reforms are intentional, well planned, and highly regulated in order for the society to establish a 163 relatively standard and stable linguistic system. For particular purposes and needs, language reform in a particular society can be gradual or drastic.8 Both Japan and China have witnessed some significant language reforms for some similar but not same purposes. The simplification of traditional Chinese characters (often also called ‘classical’, ‘complex’ or ‘non-simplified’ Chinese characters) in Japan and China, to whatever extent it may be (i.e., partial or complete), can be recognized as a typical example of highly motivated and drastic language reforms. This paper assumes that the effects of any language reform are the outcomes caused by particular motivations. Below is a brief review of motivations for simplifying Chinese characters in Japan and China. Their respective effects are introduced in the next section. Let us first take a look at the complexity of Chinese characters. Most Chinese characters during the initial phase are logographic signs, indicating both the sound and meaning of the morphemes they represent. In the literature of traditional Chinese philology, these characters fall into three major groups according to the principles underlying their graphic structure: ‘pictographic’ (xiàngxíng), ‘ideographic’ (zhĭshì), and ‘compound indicative’ (huìyì). Pictographic characters bear a physical resemblance to the objects they indicate. For example, characters like 日 rì ‘sun’, 月 yuè ‘moon’, 山 shān ‘hill’ and 水 shuĭ ‘water’ are pictographic. Supplementary to pictographic characters are idiographic ones, for which a more diagrammatic method is used to represent more abstract concepts. For example, 上 shàng ‘up’ and 下 xià ‘down’ are such idiographic characters. To make characters more complicated are compound indicative ones, which combine graphs of pictographic and ideographic characters based on their semantics to create new characters that imply a combination of the meanings of the component parts. For example, 从 cóng ‘follow’ is made of two 人 rén ‘person, with one after the other (Norman 1988; Chen 1999). As introduced in the preceding section, kanji, since its introduction to Japan, has become one of the indispensible components of the Japanese language, playing its designated role together with the other two components in the Japanese writing system. Different from hiragana and katakana, kanji writing contains a very complex orthographic system. The complexity of kanji writing is obviously created by the peculiar nature of Chinese scripts, especially traditional classical Chinese scripts. Chinese characters (kanji) introduced to the Japanese language turned out to be too difficult to read and write or remember. In order to read and write anything more than the simplest and most basic text, one needed sufficient knowledge of many thousands of Chinese characters. In order to make the writing system of kanji less complicated in Japanese everyday life, especially in popular education, publication, and documentation, in 1946, following World War II, the Japanese government instituted a series of orthographic reforms, which were carried out in several targeted areas. First, the Chinese characters in Japanese were selectively given simplified glyphs (i.e., orthographic simplification), called 新字体 shinjitai (new character form) (cf. Kobayashi 1989; Takebe 1979).9 Second, the number of characters in circulation was reduced, and formal lists of characters to be learned during each grade of school were established. Third, many variant forms of characters and obscure alternatives for common characters were officially discouraged. All this was done with the goal of facilitating learning for children and simplifying kanji use in literature and periodicals. Compared to Chinese, the Japanese reform was more directed, affecting only a few hundred characters and replacing them with simplified forms, most of which were already in use in Japanese cursive script. What should 164 be noticed is that the 当用漢字 Tōyōkanji were officially declared by the Japanese Ministry of Education in 1946, and the list of 1850 characters were published in 1949, including approximately 500 simplified characters, among which some were adopted directly from the Chinese simplified characters, and others were selectively simplified in Japan. However, according to a slightly modified version of the 当用漢字 Tōyōkanji, 95 so-called new forms of characters were added and included in 常用漢字 Jōyōkanji in 1981. Thus, the total number of 1945 official 常用漢字 Jōyōkanji, also called ‘Daily-use kanji’ or ‘Educational kanji’ and shinjitai simplifications, were established by the Japanese government in 1981 to replace the 当 用漢字 Tōyōkanji (cf. Kindaichi 1978; Kaiser 1991; Seeley 1995; Mitamura 1997; Yoshida 1981). Although most of the simplified Chinese characters in use today are the result of the large scale language reform movement launched by the government of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in the 1950s and 1960s, character simplification predates the founding of the PRC in 1949. Towards the end of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) and early Republican era of China’s history, there was push towards modernization and language reform. Discussions on character simplification took place within the Nationalist Government (i.e., the Kuomintang Government) in the 1930s and 1940s, and a large number of Chinese intellectuals and writers long maintained that character simplification would help boost literacy in China. In 1935, the Nationalist Government proposed 324 simplified characters but due to opposition, they were withdrawn. It was the first time that attention was drawn to the standardization of simplified characters (cf. Norman 1988; Chen 1999; DeFrancis 2006). The Chinese script reform attracted serious attention and gained momentum at the turn of the twentieth century. A process of rebuilding a devastated country after the founding of the PRC in 1949 brought the chance for the nationwide language reform. It was argued that the traditional Chinese script was to a large extent responsible for the country’s high illiteracy rate and stood as an impediment to the process of building a new country. There were several obvious motivations for the New China’s language reform. First, traditional characters were too difficult to learn. In Modern Chinese there is an average of eleven strokes per character, and to differentiate between characters, the configurations of these strokes become necessarily complex. Also, the graphic shape of the characters provides little indication of their pronunciation. Thus, learning to read and write thousands of graphically complex characters becomes a massive mnemonic task. The difficulty was further caused by the graphic structure in which a large number of the graphemes of the xiàngxíng, zhĭshì, and huìyì categories have lost most if not all traces of the iconicity of the original shape, and become mere mnemonic symbols (i.e., symbolic marks). Furthermore, a large number of graphs originally incorporated into xíngshēng characters as phonetic or semantic determinatives were lost (Qiu 1988). Consequently, learners can do little with such symbolic marks beyond rote memorization (Zhou 1979; Wu & Ma 1988; Chen 1988). Second, owing to the complicated nature of the graphic structures, the use of such a large number of characters as basic graphemes makes the Chinese writing system a very clumsy and inconvenient tool for many purposes, such as indexing and retrieving (Chen 1999). Third, without a large scale simplification of characters and their standardization in Modern Chinese, the elimination of illiteracy and promotion of general education to everyone in the socialist China would be too 165 difficult or impossible. In other words, Chinese script reform became a crucial and urgent part of the Chinese government’s language policy and planning.10 Mao Zedong, Chairman of the PRC (1949-59) and of the Chinese Communist Party (1943-76), made three specific directive points: developing a new alphabetic scheme that was “national in form,” promoting Putonghua by using ‘Pinyin’ Roman letters as the exclusive national standard, and placing primary emphasis on simplification of characters. The National Script Reform Congress met in 1955 to discuss specific issues of Chinese language reform with a focus on standardization and simplification of characters. It issued a directive to promote the teaching of Putonghua and to introduce standardized simplified characters. The official announcement of the Chinese Character Simplification Scheme was made in January 1956, and a set of simplified characters was published containing 515 simplified characters (jianti characters 简体字). In 1964, this number was expanded to an approximate total number of 2238 (Lu 2005; Suzuki 1989). As predicted, such a large scale simplification of characters will continue to serve the country’s long-term educational needs and today’s computer technology and worldwide information age (cf. Chen 1999). Orthographic effects of simplified kanji As explained above, the Chinese characters which were borrowed into Japanese are now called ‘kanji’ in the sense that they have become an indispensible component of the Japanese language and play a special role in its lexical structure and writing system. This paper assumes that unlike most phenomena of lexical borrowing as evidenced in most languages, Japanese lexical borrowing took place not merely because of so-called lexical-conceptual gaps between the borrowing or receiving language and the source language but because of the compositional nature of the Japanese language itself. To develop and establish its own writing system, Japanese needs to borrow or ‘import’ certain characters (i.e., lexical items) from China to serve its own linguistic purposes. Also, unlike the traditional notion of ‘adaptation’ of borrowed items to the existing linguistic structure of the borrowing language (i.e., at the levels of syntax, morphology, and phonology), a good number of borrowed Chinese characters went through some orthographic reforms such as simplification to become kanji of their own orthographic features (i.e., lexical forms) (cf. Morohashi, Watanabe, Kamata & Yoneyama 1963; Chūnichidaijiten Hensansho 1988). As introduced in the preceding section, this paper further assumes that such ‘reformed’ lexical forms through simplification are intentional and selective. In addition to making kanji writing and reading easier or more accessible to the general public, the simplification of certain Chinese characters has resulted in particular orthographic effects in Japanese lexical composition. The orthographic effects of some simplified kanji can be categorized as follows in comparison with those of simplified characters in Modern Chinese. For the current study, the categorization and categories are based on 常用漢字 Jōyōkanji and are intended to be representative rather than exhaustive (cf. Yoshida, Takeuchi & Harisu 1982; Kindanichi, Kindaichi, Kenbō & Shibata 1982; Amanuma & Katō 1982). (Note: The English glosses of the traditional Chinese characters listed below are based on the most commonly recognized meanings of individual words in Modern Chinese, without their 166 combination with other words. Also, these glosses do not indicate the parts of speech of individual words.) A. The simplified Japanese kanji with the same forms as those of the simplified characters in Modern Chinese (Japanese used simplified Chinese characters) Simplified Japanese kanji 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 医 欧 画 学 会 旧 献 恋 声 国 辞 寿 写 尽 台 虫 断 点 党 灯 体 宝 礼 乱 与 ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← Traditional Chinese characters Simplified Chinese characters 醫 歐 畫 學 會 舊 獻 戀 聲 國 辭 壽 寫 盡 臺 蟲 斷 點 黨 燈 體 寶 禮 亂 與 → → → → → → → → → → → → → → → → → → → → → → → → → (medical science/medicine) (Europe) (draw/paint; picture) (study/learn) (meet; meeting) (old) (dedicate) (love) (sound/voice) (country) (diction) (longevity/life) (write) (utmost) (table/desk, platform) (insect) (break/cut off) (spot/dot/point) (political party) (lamp/light) (body/substance/style) (treasure/precious) (courtesy/manners/gift) (in disorder; mix up) (give/offer; and) 医 欧 画 学 会 旧 献 恋 声 国 辞 寿 写 尽 台 虫 断 点 党 灯 体 宝 礼 乱 与 The representative simplified kanji listed under ‘A’ turn out to have the same forms as those of the simplified characters in Modern Chinese. It is possible that Japanese simply adopts them 167 without further simplification or modification for convenience. It becomes obvious that such simplified kanji reduce the complexity of the traditional Chinese characters. B. The simplified Japanese kanji with the different forms from those of the simplified characters in Modern Chinese (Japanese kanji: simplified by Japanese; Chinese hanzi: simplified by Chinese) Simplified Japanese kanji 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 円 応 歓 価 芸 気 剣 薬 剤 渋 従 畳 焼 図 摂 対 歯 発 豊 猟 霊 竜 塁 齢 労 ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← Traditional Chinese characters Simplified Chinese characters 圓 應 歡 價 藝 氣 劍 藥 劑 澁 從 疊 燒 圖 攝 對 齒 發 豐 獵 靈 龍 壘 齡 勞 → → → → → → → → → → → → → → → → → → → → → → → → → (round; Chinese monetary) (agree; answer; should) (happy/pleased; like) (price; value) (skill/craftsmanship; art) (air; smell; spirit) (sword; saber) (medicine/drug) (chemical preparation; dose) (astringent; rough; difficult) (from; follow) (pile up; fold) (burn; cook; fever) (picture; chart; map) (absorb; take a photograph) (answer; correct) (tooth) (hair; send out) (plentiful; bounteous) (hunt) (quick; effective; spirit) (dragon; imperial; dinosaur) (rampart; baseball base) (age/years) (work; hard) 圆 应 欢 价 艺 气 剑 药 剂 涩 从 叠 烧 图 摄 对 齿 发 丰 猎 灵 龙 垒 龄 劳 168 The representative simplified kanji listed under ‘B’ show different forms from those of the simplified characters in Modern Chinese. This indicates that Japanese may simplify some traditional Chinese characters in its own preferred way of writing, resulting in certain special forms of simplified kanji. C. The simplified Japanese kanji with the variant forms of traditional Chinese characters different from those simplified in Modern Chinese (Japanese kanji used Chinese variant forms which most of them abandoned in the classical Chinese, they are not papered in any newly published dictionaries) Simplified Traditional Simplified Japanese kanji Chinese characters Chinese characters 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 9. 10. 11. 13. 14. 15. 囲(異体字) disused 塩(異体字) disused 関(異体字) using 処(異体字) disused 粛(異体字) disused 並(異体字) using 廃(異体字) disused 獣(異体字) disused 荘(異体字) disused 戯(異体字) disused 暁(異体字) disused 覧(異体字) disused ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← 圍 鹽 關 處 肅 竝 廢 獸 莊 戲 曉 覽 (surround/enclose) (salt) (close; turn off; lock up) (get along; deal with; place) (respectful; solemn) (equally; simultaneously) (waste; useless; give up) (beast/wild animal) (village; manor) (drama; play) (dawn/daybreak; know) (look at; display/exhibit) → → → → → → → → → → → → 围 盐 关 处 肃 并 废 兽 庄 戏 晓 览 The representative simplified kanji listed under ‘C’ show some ‘simplification’ but more of the variant forms of some traditional Chinese characters. The purpose of doing so might be to make the forms of certain traditional Chinese character a bit simple but look more like kanji. According to the biggest dictionaries of the Chūnichi daijiten and Hanyu dacidian (cf. Aichi University Chinese-Japanese Dictionary editing/compilation, 1987; the 12 series of the Hanyu Dictionary editing/compilation, 1994), most variant forms are not using in modern Chinese even do not appear in recently published Chinese dictionaries. A few variant forms are used in classical Chinese literature or in Taiwan but most of them are disused. D. The simplified Japanese kanji with partially created forms or partially variant forms of traditional Chinese characters Simplified Japanese kanji Traditional Chinese characters 169 (Partially created forms by Japanese) 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 圧 壱 仮 恵 黒 剰 巣 粋 蔵 兎 稲 拝 仏 払 氷 戻 ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← ← 压 (press; push; control) 壹 (one) 假 (false/fake; supposing) 惠 (kind; benevolent; benefit) 黑 (black) 剩 (be left; remain) 巢 (nest; lair) 粹 (pure/unadulterated) 藏 (hide/conceal; store) 兔 (rabbit/hare) 稻 (paddy/rice) 拜 (do obeisance; salute) 佛 (Buddha/Buddhism) 拂 (stroke; touch lightly; whisk) 冰 (ice; feel cold) 戾 (tear/teardrop) (Partially variant forms 異体字) 17. 収 (異体字) using 18. 19. 20. 乗(異体字) disused 酔(異体字) using 妬(異体字) using ← ← ← ← 收 (receive; accept) 乘 (ride; take advantage of) 醉 (drunk/tipsy) 妒 (jealous; envy) The representative simplified kanji listed under ‘D’ are partially created forms or partially variant forms of certain traditional Chinese characters which are not simplified in Modern Chinese. It seems obvious that Japanese may create certain forms or exploit some existing variant forms during the process of selectively simplifying the traditional Chinese characters. E. The simplified Japanese kanji with only the right side components simplified like those simplified in Modern Chinese (some left redial are also simplified in Chinese but no redial change in Japanese) Simplified Japanese kanji 1. 2. 絵 駆 Traditional Chinese characters ← ← 繪 (paint/draw) 驅 (drive; expel; run) Simplified Chinese characters → → 绘 驱 170 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 継 証 称 鉄 独 ← ← ← ← ← 繼 證 稱 鐵 獨 → (prove; testify; evidence)→ (call; say) → (iron) → (alone; in solitude; only) → (continue; follow) 继 证 称 铁 独 The representative simplified kanji listed under ‘E’ show that some particular left side components of traditional Chinese characters remain the same, but the right side components of these characters are simplified like those in Modern Chinese. F. The simplified Japanese kanji with only the right side components simplified but different from those simplified in Modern Chinese (some left redial are also simplified in Chinese but no redial change in Japanese) Simplified Japanese kanji 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 駅 犠 拡 験 軽 譲 読 Traditional Chinese characters ← ← ← ← ← ← ← 驛 犧 擴 驗 輕 讓 讀 → (sacrificial animal) → (expand/enlarge; extend) → (examine/test; check) → (light; easy) → (yield; allow) → (read) → (post; courier station) Simplified Chinese characters 驿 牺 扩 验 轻 让 读 The representative simplified kanji listed under ‘F’ again show that some particular left side components of traditional Chinese characters remain the same, but the right side components of these characters are simplified differently from those in Modern Chinese. The above categories of Japanese simplified kanji provide some interesting evidence that Japanese simplification of traditional Chinese characters has produced various forms. In addition to the same simplified forms as those in Modern Chinese, a good number of simplified traditional Chinese characters in the Japanese language contain their particular forms, either different simplified forms, partially simplified forms, partially variant forms or a combination of simplified components with those traditional ones. All this may indicate that the traditional Chinese characters borrowed into the Japanese language have become a significant component of the Japanese writing system, whether such borrowed items have gone through simplification in various ways or not. That is, the borrowed Chinese characters now become the Japanese kanji to serve the purpose of the Japanese language itself.11 171 Conclusion: Implications of Japanese simplification of Chinese characters As a conclusion of this study, the above categorization of some typical orthographic effects of some most commonly observed simplified Chinese characters in Japanese offers the following important implications for understanding the nature and process of Japanese simplification of Chinese characters and the notion of lexical borrowing from a different perspective: First, unlike most phenomena of lexical borrowing caused by lexical-conceptual gaps, Japanese borrowed Chinese characters mainly to develop its own writing system. As explained earlier, as one of the components of the Japanese language, kanji plays its special and independent role in the Japanese writing system, and its role differs from that of hiragana or katakana. In other words, the linguistic motivation of Japanese lexical borrowing from Chinese is fundamentally different from that of lexical borrowing as observed in other languages. Second, unlike the established linguistic principle of ‘adaptation’ which governs the structural configurations of borrowed items in the borrowing language (i.e., borrowed items must be adapted to the syntactic, morphological, phonological, and semantic structure of the borrowing language), some Chinese characters borrowed into Japanese were orthographically reformed by means of simplification or creation to make borrowed Chinese characters into Japanese ‘kanji’ as part of the Japanese lexicon. Third, all language reforms must be driven by particular motivations in a particular society, whether such motivations are sociopolitical, socioeconomic, linguistic or educational. The orthographic reform of Chinese characters in Japan is no exception. Like the simplification of traditional Chinese characters in China, simplifying Chinese characters in Japan was to reduce the complexity and difficulty of Chinese characters in order to make reading, writing, and learning easier and more accessible to the general public. Unlike the large scale and nationwide language reforms in China, especially after the founding of the PRC in 1949, the language reform (i.e., orthographic reform) in Japan was selectively conducted. Only those which seem to be too difficult were simplified. This paper has explored the nature of the Japanese borrowing of Chinese characters into its peculiar writing system, and it has also described and explained the Japanese simplification of Chinese characters as driven by Japan’s social and educational motivations. Lexical borrowing together with highly motivated and well planned language reforms as evidenced in the Japanese language provides a new window into not only the phenomenon of linguistic borrowing itself but also the nature of a particular language. References Aichi University Chinese-Japanese Dictionary editing/compilation (1987). Chūnichi daijiten (Second edition). Tokyo, Japan: Daishūkan. Amanuma, Yasushi, and Katō, Akihiko (1982). Yoji yogo shinhyōki jiten (New edition). Tokyo, Japan: Daiichi Hoki. Chen, Ping (1999). Modern Chinese: History and sociolinguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Chen, Weizhan (1988). Wŏ duì Hànzì qiántú de yixiē kànfă. In Seminar, 39-49. DeFrancis, John (2006). The prospects for Chinese writing reform. http://www.sino-platonic.org 172 Hanyu Dictionary editing/compilation, (1994). Hanyu Dacidian (Series:1-12). Shanghai, China: Hanyu dacidian Publishing. Haugen, Einar Ingvald (1972). The ecology of language. Standford University Press. Kaiser, Stephen (1991). Introduction to the Japanese writing system. In Kodansha’s Compact Kanji Guide. Tokyo, Japan: Kondansha International. Kindaichi, Haruhiko (1978). The Japanese language (Translated and annotated by Umeyo Hirano). Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle Company, Inc. Kindaichi, Kyōsuke, Kindaichi, Haruhiko, Kenbō, Hidetoshi, and Shibata, Takeshi (1982). Sanseido kokugo jiten (Third edition). Tokyo, Japan: Sanseido Press. Kobayashi, Kazuhito (1989). Kōzanihongo to nihongo kyōiku. Vol.8, 63-96. Tokyo, Japan: Meijishoin. Lu, Gusun (2005). The English-Chinese dictionary (Unabridged). Shanghai, China: Shanghai Translation Publishing House. Makino, Seiichi, Hatasa, Yukiko Abe, and Hatasa, Kazumi (1998). Nakama I: Japanese communication, culture, context. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company. Mitamura, Joyce Yumi, and Mitamura, Yasuko Kosaka (1997). Let’s learn kanji. Tokyo, Japan: Kondansha International. Morohashi, Tetsuji, Watanabe, Suego, Kamata, Tadashi, and Yoneyama, Toratarō (1963). Shinkanwa jiten (Revised edition). Tokyo, Japan: Daishukan Shoten. Myers-Scotton, Carol (2002). Contact linguistics: Bilingual encounters and grammatical outcomes. New York: Oxford University Press. Norman, Jerry (1988). Chinese. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Poplack, Shana., Sankoff, David., and Miller, Christopher (1988). The social correlates and linguistic processes of lexical borrowing and assimilation. Linguistics, 26, 47-104. Qiu, Xigui (1988). Wénzìxué gàiyào. Beijing, China: Shangwu Yingshuquan. Romaine, Suzanne (1995). Bilingualism. Oxford: Blackwell Seeley, Christopher (1995). The 20th century Japanese writing system: Reform and change. Journal of the Simplified Spelling Society, J19, 1995/2, 27-29. Suzuki, Yoshiaki (1989). Kōzanihongo to nihongo kyōiku. Vol.6, 140-168. Tokyo, Japan: Meijishoin. Takebe, Yoshiaki (1979). Nihongo no hyōki. Tokyo, Japan: Kadokawa shoten. Tohsaku, Yasu-hiko (1994). Yookoso!: An invitation to contemporary Japanese. New York: McGrae-Hill. Weinreich Uriel (1979). Languages in contact: Findings and problems. New York: Mouton Publishers. (Originally published in 1953 as No. 1 in the series “Publications of the Linguistic Circle of New York.”) Wu, Zhankun, and Ma, Guofan (1988). Hànzì hé hànzì găigé shĭ. Changsha, China: Húnán Rénmín Chūbănshè. Yoshida, Seiichi, Takeuchi, Hitoshi, and Harisu, J. B. (1982). Shinsōgō kokugo jiten. Tokyo, Japan: Obunsha. Zhou, Hongbo (2003). Xinhua Xinciyu Cidian. Beijing, China: Shangwu Yinshuguan Publishing. Zhou, Youguang (1979). Hànzì găigé gàilùn. Third Edition. Beijing, China: Wénzì Găigé Chūbănshè. NOTES: 173 1 The study of Japanese ‘linguistic borrowing’ presented in this paper differs from most previous studies which only focused on what lexical items tend to be borrowed to meet the receiving language’s linguistic needs and how such borrowed items are adapted to the borrowing language’s existing linguistic structure at several levels, such as phonological level, morphological level, and syntactic level. This study investigates some formal and functional peculiarities of Chinese characters borrowed in Japanese through some necessary simplification or transformation ‘beyond’ linguistic borrowing as traditionally defined and described. It focuses on some specific motivations for simplifying certain borrowed Chinese characters and their orthographic effects on so-called ‘kanji’. 2 The term ‘linguistic borrowing’ is broad enough for the phenomenon of incorporation of some linguistic elements from one language into another language. Since such linguistic borrowing is most commonly observed in borrowed lexical items, the term ‘lexical borrowing’ is narrow enough for the descriptive purpose. 3 Different from the traditional notion of lexical borrowing, the borrowing of Chinese characters into Japanese is ‘idiosyncratic’ in the sense that such a type of lexical borrowing becomes peculiar to or distinctive of the nature of the Japanese language itself. In other words, kanji (i.e., Chinese characters as borrowed) becomes an indispensible component of the Japanese language beyond its lexical needs themselves. 4 In addition to the general purpose of simplifying Chinese characters in both China and Japan, the simplification of certain Chinese characters in Japan is motivated for other particular linguistic and sociolinguistic purposes. Thus, different from the traditional notion of lexical borrowing, Chinese characters once borrowed into Japanese become ‘kanji’ through some necessary transformation. Simplification is regarded as one of Japanese linguistic strategies. 5 Different from the traditional notion of lexical borrowing, certain Chinese characters borrowed into Japanese no longer keep their original meanings. This is because certain borrowed lexical items are not for their conceptual or referential content but are used for other semantic purposes. Thus, it is reasonable to state that such Chinese characters are not simply ‘borrowed’ but also created or ‘made in Japan’. 6 ‘Kanji’ is a system of Japanese writing using Chinese-derived characters. That is, borrowed Chinese characters (i.e., kanji) are used in the Japanese language for its own linguistic purposes. For example, in the late 19th century and early 20th century Japanese used Chinese characters to translate some European words. Such translated words by means of Chinese characters are called ‘wasei-kango’ (和製漢語), meaning such Chinese characters are actually made in Japan. According to the 25th report of the Japanese National Language Research Institute (1964), the number of kanji occupies approximately 41.3% of the linguistic sources of the Japanese language. 7 The distinction between ‘kanji’ and ‘hanzi’ becomes necessary and important. The term ‘kanji’ is reserved for the Japanese use of Chinese characters for its own linguistic purposes, such as in writing and in translating certain European words. Kanji, which may differ in their semantic content from those originally borrowed from Chinese. The term ‘hanzi’ is reserved for the original Chinese characters with their original lexical content. 8 As observed in linguistic and sociolinguistic literature, language reform or change tends to be ‘gradual’ in the sense that it may take centuries or generations for the reform or change to become stabilized or established. However, language reform or change in a particular society may become ‘drastic’ in the sense that a particular government may initiate and launch a nation-wide language reform movement in a relatively short period of time, as observed in the PRC after its founding in 1949, to achieve the objectives as specified in the government’s language policy and planning. Language reform or change can be ‘drastic’ also in the sense that the reform or change becomes a large scale (i.e., extensive) linguistic movement, rather than superficial or limited modification. 9 The term ‘新字体’ (shinjitai) differs from ‘简体字’ (jianti characters). Japanese ‘新字体’ includes not only all simplified or reformed Chinese characters but also all adopted Chinese characters to cover all commonly used kanji. The purpose is to standardize the writing system. However, Chinese ‘简体字’ only refers to the simplified form of 174 any Chinese characters. The purpose is to standardize all simplified forms and to make the reading and writing of such simplified forms easy. 10 The main purpose of the Chinese large scale script reform after the founding of the socialist China in 1949 was to create equal educational opportunities for all by making reading and writing Chinese characters easier and more accessible than before. Another purpose was to establish and standardize the new writing system as part of the government’s language policy and planning. In the case of Japanese simplification of the borrowed Chinese characters, the purpose was beyond making reading and writing easier. 11 Different from the traditional notion of lexical borrowing, the Chinese characters borrowed into the Japanese language are not simply for the so-called lexical-conceptual gaps but for the linguistic needs of the Japanese language. As one of the indispensible components of the Japanese language, the borrowed Chinese characters become kanji through certain necessary script modifications or changes to serve particular linguistic purposes of the Japanese language itself. In other words, kanji are closely related to original Chinese characters in terms of their script forms, but they obtain their own semantic features in the Japanese language.