Glaciers, from A to Z (2 million years ago to present)

advertisement

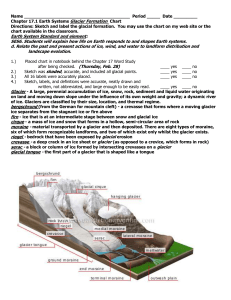

Minnesota Glaciers (2 million years ago to present) From: MN DNR For more reading on Lake Agassiz…Child of Ice… www.und.edu/instruct/eng/fkarner/pages/agassiz.htm#character The current landscape results largely from glacial activity during the Quaternary Period (2 million years ago to the present). Minnesota's present climate, with its cyclic warm and cold seasons, became established during this time. Glaciers "warehoused" huge quantities of the earth's water supplies, lowering ocean levels and expanding continental boundaries. Plant and animal communities migrated, adapted selectively, or became extinct with the changing climate. Minnesota saw the advance and retreat of several major, successive periods of continental ice sheets. Glacial advances All Read The gigantic Laurentian Ice Sheet, centered in what is now the Hudson Bay, grew and retreated with climatic changes throughout the Ice Age. During colder periods, it extended southward across the upper Midwest in what are called glaciations, each named for a geographic area: Nebraskan, Kansan, Illinoian, and Wisconsin. The Wisconsin glacial event, the most recent, had `the last word' as it created the surface features we live with today. Beginning about 75,000 years ago, it, too, experienced periodic growth and decay with changing conditions. Its advances produced tongues of ice called lobes, each named for a specific geographic area: Wadena, Rainy, Superior, and Des Moines. Each lobe also experienced periodic growth and decay. The Wadena Lobe advanced from the north several times. Its last advance deposited the Alexandria moraine (which was later reglaciated), the Itasca moraine, and the drumlin fields spanning Otter Tail, Wadena, and Todd counties. The Rainy and Superior Lobes came out of the northeast and advanced, sometimes with and sometimes independently of the Wadena. Its last advance left a coarsetextured till of basalts, gabbro, granite, iron formation, red sandstone, slate, and greenstone strewn across the northeastern half of Minnesota and as far south as the Twin Cities. The Des Moines Lobe originated in the northwest and advanced in a southeasterly direction across Minnesota and into Iowa. Its fine-textured till consisted of limestone, shale, and granite fragments, from which developed the fine prairie (now agricultural) soils found in these areas. Earlier lobes and glaciations also left their marks, though their effects are generally buried beneath more recent glacial drift. We occasionally glimpse the underlying till that is distinctive of their origin, or the striations on bedrock outcrops that indicate their direction of travel. They echo much earlier times. A Glacier defined Because glaciation is so significant to understanding today's landforms, it warrants a closer look. A glacier is a large body of ice moving slowly across a land surface. It forms when snow accumulates faster than it melts over a long period of time. Under the weight of the ice mass, a sole of ice melts at the bottom and allows the glacier to move. A glacier also moves by internal, plastic flow. The ice mass shrinks or expands yearly, reflecting the net effect of the year's weather. B Glacial erosion Glaciers sculpt the surface of the earth as they expand, cutting through relatively soft materials, picking up occasional pieces of rock or debris along the way, and depositing them further on. As the base picks up various sizes of debris, it acquires texture and abrasive power that varies much like grades of sandpaper. On some bedrock outcrops today, parallel lines scar the surface, indicating that a rock frozen into the glacier's sole passed here long ago. These markings are called striations, while wider, deeper markings are known as grooves. Finely textured particles in the sole produced highly polished rock surfaces, much like fine sandpaper. Striations and grooves are helpful in identifying the direction of the glacial flow that took place on a given site. C Glacial deposits The glacier deposits its collection of rocks and debris in a variety of ways. Glacial deposits, generally, are called drift. However, other terms are more descriptive of the materials and their formation. A collection of debris, unsorted by size or substance, is known as till. Single rocks deposited far from their source are known as erratics. A thin blanket of low hills and lowlands laid down while the glacier is moving is called ground moraine. Ground moraine that has been molded into streamlined hills with its long axes parallel to the direction of ice flow is called a drumlin field. An end moraine is an irregular, hilly deposit of till at the ice margin or toe of the ice sheet; The Alexandria area is a fine example. Figure 1.4. Glacial formations. D Often a huge chunk of ice, buried by debris, becomes isolated from the glacier. It then slowly melts, and leaves a collapsed pit of debris. This is called a kettle or ice-block, which often becomes a kettle lake when conditions are right. In the prairie, these are called potholes. Most of the lakes in the Alex area can trace their origins to this beginning. Along the margins of the glacier, wet sediment collects, then settles and slumps, forming hummocks and uneven terrain. A chain of lakes often forms along these glacial margins. E Stagnant ice sometimes forms a melt out depression that fills with outwash deposits when the rest of the ice melts. This leaves a conical hill called a kame. Seven Sisters Hill on Lake Christina is a great example of this. Recurrent melting within the glacier creates streams of meltwater that tunnel through the ice mass. These streams carry debris, which may actually plug a tunnel, resulting in the formation of a new tunnel. Later, when the glacier melts away, this plug is left on the land in a long, molded ridge of sand and gravel called an esker. Ripley Esker SNA, just north of Little Falls, protects a fine example of such a plug. If the stream carries the debris outside the glacier, it may be deposited as outwash, or sorted sand and gravel sediment deposited along the stream bed. The area just south of I-94 and Alex constitute an outwash plain. The tundra-like climate of the Ice Ages produced wind that also moved glacial debris; it could pick up the finely textured silt and deposit it downwind in what is called loess. The soils across western and southern Minnesota contain loess, a constituent of prairie soils. Glacial lakes and rivers F Glacial lakes are another great legacy of the glaciers. All were dammed on one side by the ice sheet and many approached the scale of a sea. Glacial Lake Agassiz was the largest. Fluctuating in size and depth, it left behind a series of beaches that now outline the broad, flat Red River Valley. Others include Glacial Lakes Benson, Aitkin, and Duluth. From time to time these glacial lakes overflowed, and cut huge river channels. At its highest level, Glacial Lake Agassiz crested a moraine at Brown's Valley and spilled over to become the Glacial River Warren. Its bed continues to drain the surrounding uplands, though the water volume of today's Minnesota River is a fraction of the original flow. Consequently, the broad river valley and high stream terraces, remnants from long ago, dwarf today's river. This is also true for today's St. Croix and Mississippi River valleys. Visit the high terrace on Bonanza Prairie SNA near Big Stone Lake to get a sense of the magnitude of the ancient river as you look across this broad lake to the bluffs in North Dakota. H G Figure 1.5. Minnesota's glacial lakes and rivers.