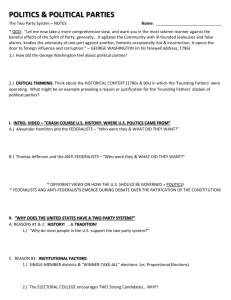

Full Text (Final Version , 523kb)

advertisement