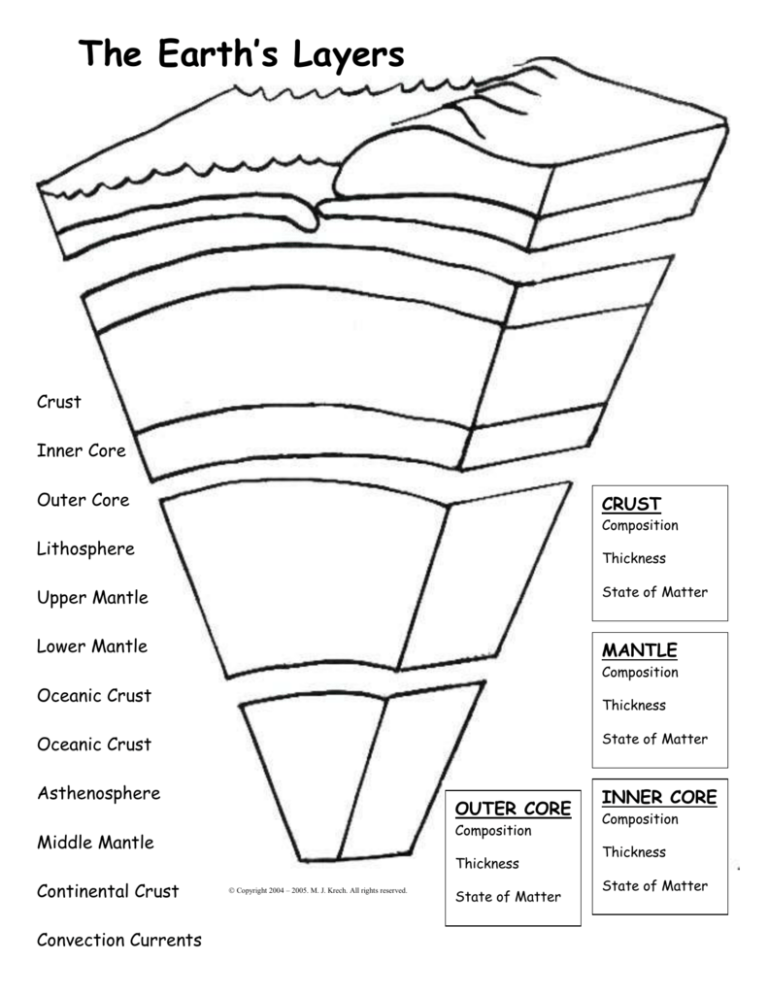

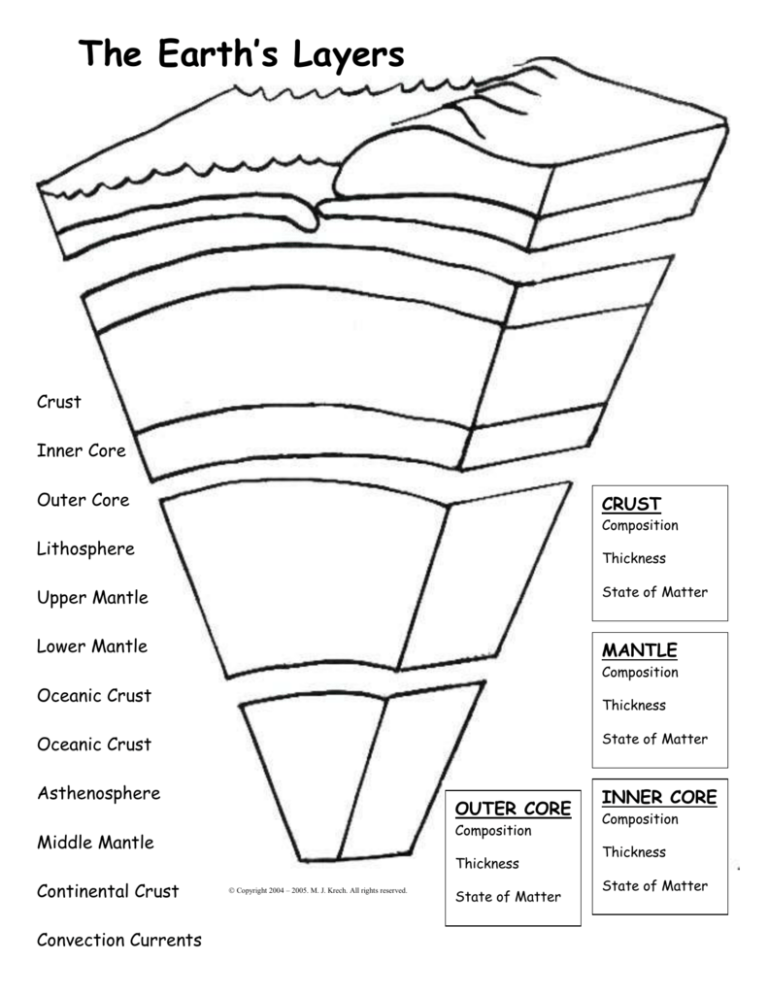

The Earth’s Layers

Crust

Inner Core

Outer Core

CRUST

Composition

Lithosphere

Thickness

Upper Mantle

State of Matter

Lower Mantle

MANTLE

Composition

Oceanic Crust

Thickness

State of Matter

Oceanic Crust

Asthenosphere

OUTER CORE

Composition

Middle Mantle

Continental Crust

Convection Currents

Thickness

Copyright 2004 – 2005. M. J. Krech. All rights reserved.

State of Matter

INNER CORE

Composition

Thickness

State of Matter

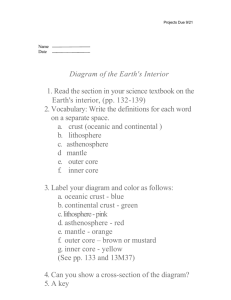

Make an Earth’s Layers FOLDABLE

NOTE: Please follow the directions carefully!

1. Color the four layers using this guide:

Inner Core – red

Outer Core – red-orange

Lower Mantle – orange

Middle Mantle – light orange

Upper Mantle – yellow

Oceanic Crust – dark brown

Continental Crust – light brown

Ocean – blue

Convection Currents – Black Marker (lines)

2. Fill out the small squares with the information for each of the main layers of the Earth.

3. Now you may cut out the layers! Also cut out the four squares, the 12 labels and the

title.

4. Set one piece of purple paper in front of you. Closely trim the title. Past “The Earth’s

Layers” title in the top left corner of the paper.

5. Paste the “Crust” right below the title, centered on the page.

6. Set the second piece of paper on top of the first, close to the bottom of the “Crust”.

7. Paste the “Mantle” on the second piece of paper near the top.

8. Carefully fold up the bottom of both papers to about ¼ inch below the bottom of the

“Mantle”, lining up the sides of the purple papers

9. Staple the fold with two staples very close to the edge.

10. Past the “Outer Core” on the next flap down.

11. Paste the “Inner Core” on the bottom flap. Paste the inner core information square to

the left of the “Inner Core”

12. Paste the three other information squares inside the flaps, next to the corresponding

layers.

13. Cut out any of the purple flaps that show.

14. Using a black pen or marker, add brackets ( } ) to indicate where the Lithosphere is

located.

Copyright 2004 – 2005. M. J. Krech. All rights reserved.

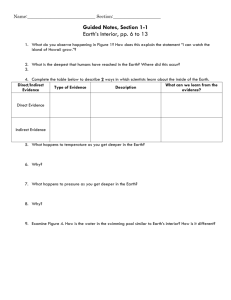

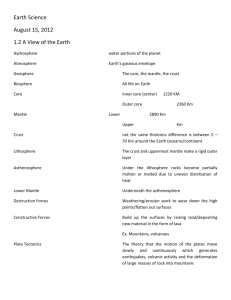

Background Information - Earth’s Layers

The Earth is a very large, very diverse and very dynamic planet. To travel straight through the planet you

would have to travel over 12,000 kilometers or around 7,500 miles! Driving 60 miles per hour, 24 hours a day,

it would take you over 5 days to go that distance! The surface can be freezing cold yet the center is made of

material that should be melted but because it is under such extreme pressure it is a solid ball nearly the

temperature of the surface of the sun. A cross-section of the Earth shows four main regions: the crust,

mantle, outer core and inner core. Read on to find out more about each layer...

The Crust

The crust is the part of the planet that you are most familiar with. You walk along its surface, hike up its faces

and tread lightly on it beneath the waves at the oceans edge. The Earth’s crust is like the thin skin of an apple.

It is many times thinner than any layer contained below, in the Earth’s interior. We divide the crust into two

distinctly different categories: oceanic and continental.

The oceanic crust, as the name implies, lies beneath the Earth’s oceans. This crust is the thinnest part of the

skin and often times, we find, the weakest. The oceanic crust ranges in depth from 4 to 7 miles (6-11 km).

Though this seems like a large distance, don’t forget it’s almost 4,000 miles to the center of the Earth! The

oceanic crust is mainly composed of a dark-colored, small-grained rock known as basalt. This rock is primarily

made up of the elements iron and magnesium. It’s because of the high iron content that geologists have been

able to determine that the magnetic poles have changed directions several times over Earth’s 4.6 billion year

history. The iron particles align themselves in the direction of the poles and from time-to-time, the poles

switch. North is south and south is north, the iron particles then orient themselves in the other direction. The

oceanic crust is more dense than the continental crust and has an average density of 3 g/cm 3.

When you look at the globe, you see that the surface of the earth consists of a lot of water (71%). The other

29% consists of land. You can divide this land into six big pieces, which are called continents. The earth's crust

is the thickest below the continental crust, with an average of about 20 to 25 miles (30 to 40 km) and with a

maximum of 45 miles (70 km). This is nearly seven times as thick as the oceanic crust. The continental crust is

older than the oceanic crust; some rocks are 3.8 billion years old. The continental crust mainly consists of

igneous rocks called granite. Granite is lightly colored and coarsely grained, quite the opposite of the oceanic

basalt. The average density of the continental crust is 2.7g/cm³. It is this density that allows the oceanic crust

to dive beneath the continental crust as they move relative to one another.

The Mantle

The mantle is immense! It traverses the interior of the Earth from the crust all the way to the outer core, a

distance of nearly 1,800 miles (2,900 km). The mantle alone makes up nearly 80 percent of the Earth's total

volume and is over 70 times as thick as the average crust. The mantle is the most diverse of the interior layers

of the Earth. We divide the mantle into three main sections, the upper mantle, the middle mantle and the

lower mantle

We’ll start with the lower mantle as it takes up the largest proportion of the total mantle. It begins around

200 miles deep and goes to the edge of the outer core at around 1,800 miles. The average temperature is

5,400F (3000C). Even at this extreme temperature the rock remains solid because of the super-high

pressures. The inner mantle for the biggest part probably consists of sulphides and oxides of silicon and

magnesium. The density is between 4.3g/cm³ and 5.4g/cm³.

The first 200 miles of the mantle are made of a very strange substance. Have you ever seen the black asphalt

that streets are often made of? Think of those streets on a hot summer afternoon. Sometimes the asphalt

gets so hot that it sticks to your shoes as you walk across a newly paved parking lot. This thick material

behaves similar to the material in the upper and middle mantle; we often call it plastic. The material ranges in

temperature from 2,500F (1400C) and 5,400F (3000C) and the density is between 3.4g/cm³ and 4.3g/cm³.

Nearer the lower regions of the mantle, the asthenosphere is a thick, tough, sludge like liquid with

temperatures around 5,000F. It is in this middle region of the mantle that the greatest difference in

temperature occurs within the Earth. The simple fact that there is nearly a 3,000F change from the top of

the asthenosphere to the bottom causes the formation of convection currents. Convection currents occur in

areas of the asthenosphere where the cooler, more dense mantel material sinks to the lower regions of the

asthenosphere where it is heated up. Once heated, the material becomes less dense and rises up to the lower

regions of the mantle where it cools and...

The upper mantle is referred to as the lithosphere. Though the lithosphere is made up of the same material

as the asthenosphere it is more rigid (more solid) due to the lower temperatures. This layer is associated with

the Earth’s crust and together they make up large pieces called lithospheric plates. These plates move

around, crashing into each other causing earthquakes and volcanoes. The convection currents generated in

the asthenosphere slowly, yet forcefully, interact with the solid, sticky lithospheric plates to move them.

Essentially, the lithospheric plates are gliding around on a sea of churning asthenosphere.

The Outer Core

As you move ever deeper into the center of the Earth, the conditions continue to become more and more

extreme. The outer core begins at around 1,800 miles (2,890 km) deep and continues until it reaches the

inner core at nearly 3,200 miles (5,150 km). With an ever-increasing amount of pressure from the material

above, the outer core’s density is around 11 g/cm³, nearly four times as dense as the granite that makes up

the continental crust miles above. Temperatures here soar as well, ranging from 7,200 – 9,000F (40005000C). The outer core is so hot that the iron and nickel that make up the material there remain in a molten,

liquid state. As in the asthenosphere the difference in temperature from the mantle boundary to the inner

core boundary cause convection currents to form in the outer core.

The Inner Core

By way of contrast, the inner core is under so much more pressure than the outer core that the density of the

iron and nickel material can be as high as 15 g/cm³. At these pressures, even though the temperature reaches

9,000 – 11,000F (5000-6000C), the inner core remains a solid ball. The convection currents in the outer core

rotate the solid inner core and it is that motion that creates

magnetism, which, in turn, creates the occurrence of the north and

south poles. At depths between 3,200 – 4,000 miles (5,150-6,370 km)

below the earth's surface we can only guess what the conditions are

really like. We use the seismic waves generated by earthquakes to

determine the temperatures and densities of the different layers of the

Earth’s interior. Seismic waves travel at different speeds through

different densities of material. A few simple calculations using arrival

times of these seismic waves from an earthquake on the other side of

the planet gives us a pretty good idea about the densities and

temperatures of the different layers.