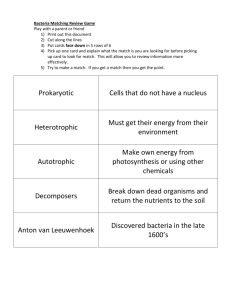

أعلى النموذج (1)Classification of Bacteria Definitions Classification

advertisement

(1)Classification of Bacteria Definitions Classification, nomenclature, and identification are the three separate but interrelated areas of taxonomy. Classification can be defined as the arrangement of organisms into taxonomic groups (taxa) on the basis of similarities or relationships. Classification of prokaryotic organisms such as bacteria requires a knowledge obtained by experimental as well as observational techniques, because biochemical, physiologic, genetic, and morphologic properties are often necessary for an adequate description of a taxon. Nomenclature is naming an organism by international rules according to its characteristics. Identification refers to the practical use of a classification scheme: (1) to isolate and distinguish desirable organisms from undesirable ones; (2) to verify the authenticity or special properties of a culture; or, in a clinical setting, (3) to isolate and identify the causative agent of a disease. The latter may permit the selection of pharmacologic treatment specifically directed toward their eradication. Identification schemes are not classification schemes, though there may be a superficial similarity. An identification scheme for a group of organisms can be devised only after that group has first been classified, ie, recognized as being different from other organisms. Criteria for Classification of Bacteria Suitable criteria for purposes of bacterial classification include many of the properties that were described in the preceding chapter. Valuable information can be obtained microscopically by observing cell shape and the presence or absence of specialized structures such as spores or flagella. Staining procedures such as the Gram stain can provide reliable assessment of the nature of cell surfaces. Some bacteria produce characteristic pigments, and others can be differentiated on the basis of their complement of extracellular enzymes; the activity of these proteins often can be detected as zones of clearing surrounding colonies grown in the presence of insoluble substrates (eg, zones of hemolysis in agar medium containing red blood cells). The use of specific antibodies can give a rapid indication of similar surface structures carried by independently isolated bacteria. Tests such as the oxidase test, which uses an artificial electron acceptor, can be used to distinguish organisms on the basis of the presence of a respiratory enzyme, cytochrome c. Simple biochemical tests can ascertain the presence of characteristic metabolic functions. Criteria leading to successful grouping of some related organisms include measurement of their sensitivity to antibiotics. The value of a taxonomic criterion depends upon the biologic group being compared. Traits shared by all or none of the members of a group cannot be used to distinguish its members, but they may define a group (eg, all staphylococci produce the enzyme catalase). In addition, genetic instability can cause some traits to be highly variable within a biologic group or even within a single cell line. For example, antibiotic resistance genes or genes encoding enzymes (lactose utilization, etc) may be carried on plasmids, extrachromosomal genetic elements that may be transferred among unrelated bacteria or that may be lost from a subset of bacterial strains identical in all other respects. 1 Identification & Classification Systems Keys Keys organize bacterial traits in a manner that permits efficient identification of organisms. The ideal system should contain the minimum number of features required for a correct identification. Groups are split into smaller subgroups on the basis of the presence (+) or absence (–) of a diagnostic character. Continuation of the process with different characters guides the investigator to the smallest defined subgroup containing the analyzed organism. In the early stages of this process, organisms may be assigned to subgroups on the basis of characteristics that do not reflect genetic relatedness. It would be perfectly reasonable, for example, for a key to bacteria to include a group such as "bacteria forming red pigments" even though this would include such unrelated forms as Serratia marcescens and purple photosynthetic bacteria. These two bacterial assemblages occupy distinct niches and depend upon entirely different forms of energy metabolism. Nevertheless, preliminary grouping of the assemblages would be useful because it would immediately make it possible for an investigator having to identify a red-pigmented culture to narrow the range of possibilities to relatively few types. Numerical Taxonomy Numerical taxonomy (also called computer taxonomy, phenetics, or taxometrics) became widely used in the 1960s. Numerical classification schemes use a large number (frequently 100 or more) of unweighted taxonomically useful characteristics. The computer clusters different strains at selected levels of overall similarity (usually > 80% at the species level) on the basis of the frequency with which they share traits. In addition, numerical classification provides percentage frequencies of positive character states for all strains within each cluster. Such data provide a basis for the construction of a frequency matrix for identification of unknown strains against the defined taxa. Computerized databases have been used to develop diagnostic tests that identify clinically relevant isolates through numerical codes or probabilistic systems. Phylogenetic Classifications: Toward an Understanding of Evolutionary Relationships among Bacteria Phylogenetic classifications are measures of the genetic divergence of different phyla (biologic divisions). Close phylogenetic relatedness of two organisms implies that they share a recent ancestor, and the fossil record has made such inferences relatively easy to draw for most representatives of plants and animals. No such record exists for bacteria, and in the absence of molecular evidence, the distinction between convergent and divergentevolution for bacterial traits can be difficult to establish. . 2 Table of Taxonomic Ranks. Formal Rank Example Kingdom Prokaryotae Division Gracilicutes Class Scotobacteria Order Eubacteriales Family Enterobacteriaceae Genus Escherichia Species coli Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology The possibility that one might draw inferences about phylogenetic relationships among bacteria is reflected in the organization of the latest edition of Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. First published in 1923, the Manual is an effort to classify known bacteria and to make this information accessible in the form of a key. A companion volume, Bergey's Manual of Determinative Bacteriology, serves as an aid in the identification of those bacteria that have been described and cultured. In 1980, the International Committee on Systematic Bacteriology published an approved list of bacterial names. This list of about 2500 species replaces a former list that had grown to over 30,000 names; since January 1, 1980, only the new list of names has been considered valid. Because it is likely that emerging information concerning phylogenetic relationships will lead to further modifications in the organization of bacterial groups within Bergey's Manual, its designations must be regarded as provisional. Description of the Major Categories & Groups of Bacteria there are two different groups of prokaryotic organisms: eubacteria and archaebacteria. Eubacteria contain the more common bacteria, ie, those with which most people are familiar. Archaebacteria do not produce peptidoglycan, a major difference between them and typical eubacteria. They also differ from eubacteria in that they live in extreme environments (eg, high temperature, high salt, or low pH) and carry out unusual metabolic reactions, such as the formation of methane. A key to the four major categories of bacteria and the groups of bacteria comprising these categories is presented in Table 3–2. The four major categories are based on the character of the cell wall: gram-negative eubacteria that have cell walls, gram-positive eubacteria that have cell walls, eubacteria lacking cell walls, and the archaebacteria. 3 Table 3–2. Major Categories and Groups of Bacteria That Cause Disease in Humans Used As an Identification Scheme in Bergey's Manual of Determinative Bacteriology, 9th Ed. I. Gram-negative eubacteria that have cell walls Group 1: The spirochetes Treponema Borrelia Leptospira Group 2: Aerobic/microaerophilic, motile helical/vibroid gram-negative Campylobacter bacteria Helicobacter Spirillum Group 3: Nonmotile (or rarely motile) curved bacteria None Group 4: Gram-negative aerobic/microaerophilic rods and cocci Alcaligenes Bordetella Brucella Francisella Legionella Moraxella Neisseria Pseudomonas Rochalimaea Bacteroides (some species) Group 5: Facultatively anaerobic gram-negative rods Escherichia bacteria) (and Klebsiella Proteus Providencia Salmonella Shigella Yersinia Vibrio Haemophilus Pasteurella Group 6: Gram-negative, anaerobic, straight, curved, and helical rods Bacteroides Fusobacterium Prevotella Group 7: Dissimilatory sulfate- or sulfur-reducing bacteria None Group 8: Anaerobic gram-negative cocci None 4 related coliform Group 9: The rickettsiae and chlamydiae Rickettsia Coxiella Chlamydia Group 10: Anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria None Group 11: Oxygenic phototrophic bacteria None Group 12: Aerobic chemolithotrophic bacteria and assorted organisms None Group 13: Budding or appendaged bacteria None Group 14: Sheathed bacteria None Group 15: Nonphotosynthetic, nonfruiting gliding bacteria Capnocytophaga Group 16: Fruiting gliding bacteria: the myxobacteria None II. Gram-positive bacteria that have cell walls Group 17: Gram-positive cocci Enterococcus Peptostreptococcus Staphylococcus Streptococcus Group 18: Endospore-forming gram-positive rods and cocci Bacillus Clostridium Group 19: Regular, nonsporing gram-positive rods Erysepelothrix Listeria Group 20: Irregular, nonsporing gram-positive rods Actinomyces Corynebacterium Mobiluncus Group 21: The mycobacteria Mycobacterium Groups 22–29: Actinomycetes Nocardia Streptomyces Rhodococcus III. Cell wall-less eubacteria: The mycoplasmas or mollicutes Group 30: Mycoplasmas Mycoplasma Ureaplasma IV. Archaebacteria Group 31: The methanogens None Group 32: Archaeal sulfate reducers None Group 33: Extremely halophilic archaebacteria None Group 34: Cell wall-less archaebacteria None Group 35: Extremely thermophilic and hyperthermophilic sulfur None metabolizers 5 Gram-Negative Eubacteria that Have Cell Walls This is a heterogeneous group of bacteria that have a complex (gram-negative type) cell envelope consisting of an outer membrane, an inner, thin peptidoglycan layer (which contains muramic acid and is present in all but a few organisms that have lost this portion of the cell envelope), and a cytoplasmic membrane. The cell shape may be spherical, oval, straight or curved rods, helical, or filamentous; some of these forms may be sheathed or encapsulated. Reproduction is by binary fission, but some groups reproduce by budding. Fruiting bodies and myxospores may be formed by the myxobacteria. Motility, if present, occurs by means of flagella or by gliding. Members of this category may be phototrophic or nonphototrophic bacteria and include aerobic, anaerobic, facultatively anaerobic, and microaerophilic species; some members are obligate intracellular parasites. Gram-Positive Eubacteria that Have Cell Walls These bacteria have a cell wall profile of the gram-positive type; cells generally, but not always, stain gram-positive. Cells may be spherical, rods, or filaments the rods and filaments may be nonbranching, or may show true branching. Reproduction is generally by binary fission. Some bacteria in this category produce spores as resting forms (endospores). These organisms are generally chemosynthetic heterotrophs and include aerobic, anaerobic, and facultatively anaerobic species. The groups within this category include simple asporogenous and sporogenous bacteria as well as the structurally complex actinomycetes and their relatives. Eubacteria Lacking Cell Walls These are microorganisms that lack cell walls (commonly called mycoplasmas and comprising the class Mollicutes) and do not synthesize the precursors of peptidoglycan. They are enclosed by a unit membrane, the plasma membrane. They resemble the L forms that can be generated from many species of bacteria (notably gram-positive eubacteria); unlike L forms, however, mycoplasmas never revert to the walled state, and there are no antigenic relationships between mycoplasmas and eubacterial L forms. 6