A Citizens Report on Recycling

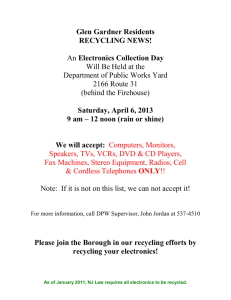

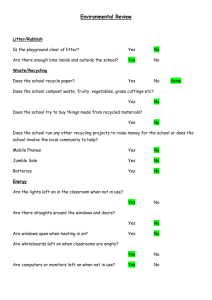

advertisement