In Re: Hingham Public Schools BSEA #11-3762

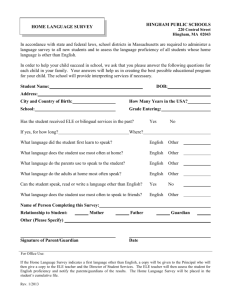

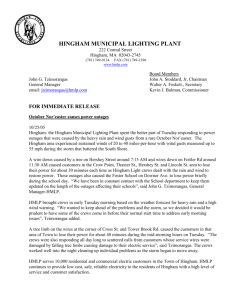

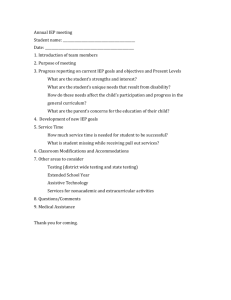

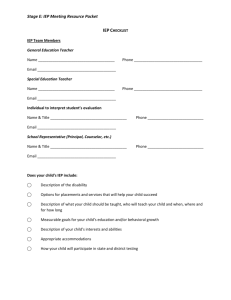

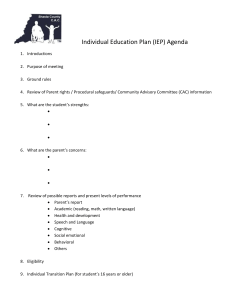

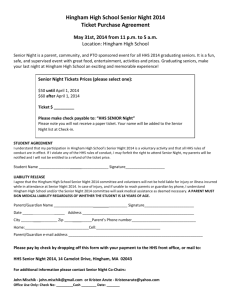

advertisement