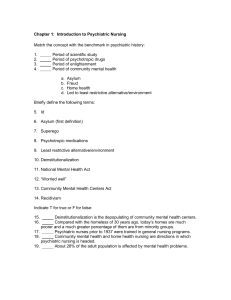

Long Term Intensive Psychiatric Treatment:

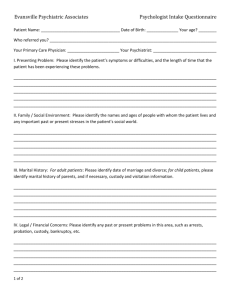

advertisement