`Behind the wall` there`s `a mop for every day`

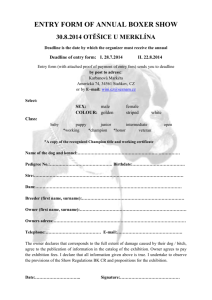

EXHIBITION

> > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > < >

THAT’S ALL FOLKS!

A clash between reason and destiny?

12.12.2009 - 17.01.2009 BRUGES

“Art becomes politically effective only when it is made beyond or outside the art market - in

the context of direct political propaganda.”

(Boris Groys, Art Power)

2009: art & politics ?

The year 2009 seemed almost destined to reflect upon the relationships between arts and politics. We did celebrate for e.g. the fall of the Berlin Wall (9 November 1989), commemorated the start of the Second World

War (1939) and the much debated election of

Barack Obama to the White House. As a result, numerous art projects referred to these events.

In the shadow of these world-famous events there is the remembrance of a local anecdote. Exactly one century ago, the legendary Mexican artist Diego Rivera (1886-

1957) visited the city of Bruges. Rivera’s stay

(November 1909) should be seen in the context of his formation years, during which he visited numerous artists, museums and other collections in Europe.

Rivera is not only the most famous muralist of the 20th century, he is also one of the best examples of politically engaged (read: leftish) artists. In addition, Rivera’s life and oeuvre provide a good summary of engaged artistry within the growing influence of a free market economy.

Enough reasons and issues to set up a contemporary project that dealt with the complex relationships between arts and politics.

Furthermore, the organisation of an exhibition on such a subject in the 21st century has lost nothing of its topicality. On the contrary, this subject has made a stunning comeback in the last two decades, a trend we have scarcely known since the early 70s of the previous century.

Particularly remarkable is the multitude of current arts practices revealing the high political interest and especially the commitment of the artist.

Art and effect?

As during the prime of politically engaged art of the previous century, works of art need to deal ‘with something’ again, need to convey a social and political message and preferably should achieve a tangible result on society at large. In this respect it’s quite remarkable that people did not derive lessons from the relative pedagogic and emancipatory impact of art, dating from the 1960s and 1970s.

Is any form of political art conceivable at all in a market-driven society, especially when we envision some form of ‘political’ result? Or is any work of art in such an environment objectified into a commodity, and its possible political content and effect consequentially neutralised?

Politically neutral art cannot exist. Any human act or product is biased, is some form of political act, but this does not entail that the content of any work is necessarily politically inspired with the intention to achieve a certain objective, a certain social effect.

‘That’s all Folks!’ is a direct, graphical exhibition with an ironic, satiric undertone with expressions of politically incorrect views. Devoid of any pedantic or didactic intentions, the exhibition, in terms of content and staging, especially had to breathe the increased mediatisation and theatralisation of current political life.

Conceived as a television studio or a political forum, the exhibition situates the visitor in the middle of a clash of chaotic images with overt and especially covert messages in a setting that breathes the world of advertisements or spin doctors.

In some of the exhibited works of art, forms of rebellion and provocation resulted in an actual danger to the environment, a disruption of the social order. Artists like Philippe Meste and

Peter Puype go far beyond the distribution of sloganesque posters or banners in the street scene and follow in the footsteps of terror, or even the terrorist.

A second angle within this project was the aesthetic criticism on politically inspired artistic projects, and here the English Art & Language collective played a decisive role.

Other artists opted for a politically incorrect strategy. Widely varying works such as: videos by Yoshua Okon, pictures and sculptures by

Robert Gligorov, the ‘Katmando’ installation by

Olivier Blanckart, the pictures by Steven Brouns, hide their critical content under the cloak of political incorrectness.

Last but not least, the virtually fatalistic works by John Isaacs dealing with the meaninglessness of the human enterprise, play a predominant role in the exhibition.

That’s All Folks?

With the figure of John Isaacs we get to a second stage of this project, namely the renewed contact with curator Jerome Jacobs.

Together with Jacobs, an expert in the field of these artists at European level, we broadened the concept of the actual exhibition. What started originally as just another exhibition dealing with the possible relationships between arts and politics, evolved towards a broader concept where questions are asked about the impact of human enterprise and humandeveloped systems on mankind and its environment.

Our civilizations, the influence of ideologies, religious beliefs and world views and the development of drastic technological innovations resulted in a series of catastrophic human conflicts. Simultaneously they led to a number of irreversible ecological processes, whereby we risk the future of our planet and our own life-form.

The thematic lines of the exhibition, such as the end of great ideologies, the impact of the market economy, the growing importance of infotainment and the development of a new political personality cult, the interwovenness of media and politics, the banalisation of war and violence, the relationships between religion and war, the existence of institutionalised prejudices and intolerance, war as a continuation of politics in a different manner, political activism etc. are set against the background of human desire to civilise and, at the same time, its inability to give a peaceful direction to its own existence, apart from its eventual destruction.

Artists

Carlos Aires, Art & Language, Olivier Blanckart,

Andrey Blokhin & Georgy Kuznetsov,

Delphine Boël, Marco Brambilla, Steven Brouns,

Daniele Buetti, Claire Fontaine, Ronald

Dagonnier, Jimi Dams, Cathy De Monchaux,

Peter Depelchin, Daniël Dewaele, Gabriele Di

Matteo, Ross Downes, Christoph Draeger,

Gardar Eide Einarsson, Fakhri El Ghezal,

Bruna Esposito, Al Farrow, Rainer Ganahl,

Robert Gligorov, Shadi Ghadirian, Bernard

Gigounon, Frances Goodman, Dumitru Gorzo,

Guma Guar, Gottfried Helnwein, Fabian Hesse,

IRWIN, John Isaacs, Thomas Israel, Dennis Kardon,

Nina Katchadourian, Olga Koumoundouros,

Franck Lesieur, Jacques Lizène, Kakudji,

Emilio Lopez-Menchero, Stefano Lupitani,

Marko Mäetamm, Marcel Mariën, Dominic

McGill, Johan Muyle, Hermann Maier Neustadt,

Yoshua Okon, Suzanne Opton, Ronald Ophuis,

Eric Pougeau, Peter Puype, Gionata Gesi Ozmo,

Frank Rannou, Walter Robinson, Samuel

Rousseau, Chéri Samba, Jens Semjan, Andres

Serrano, Stephen j Shanabrook, Bob and

Roberta Smith, Paul M Smith, Tracey Snelling,

André Stas, Mircea Suciu, Bosse Sudenburg,

Cédric Tanguy, Kurt Treeby, Gavin Turk, Guy

Van Bossche, Jan Van Imschoot, Vuk Vidor,

Herbert Weber, Bryan Zanisnik

Curators

Michel Dewilde, Jerome Jacobs

PRACTICAL INFORMATION

> > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > > < >

Hallen - Belfry, Markt 7, 8000 Bruges

December 12, 2009 - January 17, 2010

Opening hours: Tuesday to Sunday, from 1 p.m. to 6 p.m.

Closed on Mondays, December 25 and

January 1.

On December 24 and 31: closed at 4 p.m.

Free entrance

Catalogue available: 6,00 euro www.ccbrugge.be