ECOLOGICAL PHILOSOPHIES

advertisement

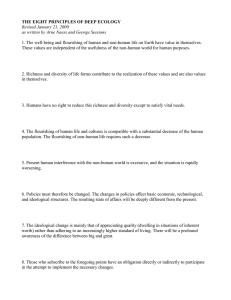

ECOLOGICAL PHILOSOPHIES Gathered from various sources by Alfred Snider Pick an environmental philosophy that seems to make sense to you and stick with it for issue identification and consistency. Anthropocentrism A term from environmental political philosophy denoting a human-centered ethical system, usually contrasted with ecocentrism. The question of the distribution of value across human and non-human nature has been one of the central preoccupations of environmental ethics over the last 30 years. The anthropocentric belief is that human beings are the sole bearers of intrinsic value or possess greater intrinsic value than nonhuman nature. It is therefore acceptable to employ the resources of the natural world for only human ends—a view that has come in for sustained criticism from ecocentric philosophers, who argue that it amounts to little more than a species bias, or ‘human racism’. Recent ecological defenses of anthropocentrism claim that an anthropocentric ethics is adequate to the task of grounding care for the natural environment. A sufficiently complex or enlightened understanding of human well being will acknowledge the value of the non-human world to humans in more than merely economic-instrumental terms. If the existence of a non-anthropogenic environment is taken as essential to human wellbeing, then demands for environmental protection can be anthropocentric in origin but no more contingent than ecocentrism claims to be; the advantage of anthropocentrism being that it allows these demands to be made within a familiar moral framework. Propertarian Private property ownership is good for saving the environment. When no one owns parts of the environment, you get the tragedy of the commons. G. Hardin (1968) described an increase in the use of common land by a number of grazers, with each grazer continually adding to his stock of animals for as long as the marginal return from each animal is positive, even though the average return for each animal is falling, and even though the quality of the grazing deteriorates. Hardin used this metaphor to describe any situation where the interests of the individual do not coincide with the interests of the community, and where no organization has the power to regulate individual behavior. Ownership increases your incentive to get the most out of your property, including longterm use. Owners want to get benefits from property without destroying it. Thus, a property owner would avoid contaminating the property with pollution. This has been seen in examples of Scottish wild areas privately owned as well as in fisheries that are privately owned not be over harvested. The reason that the ecology is damaged now is that lots and lots of it is not owned by anyone, so those parts (air, sea, downstream river) get damaged because there is no incentive to protect it. Arguments against this approach include: Focus is on human value, not value to the ecosystem, so damage is still likely to be done. Humans have a short-term focus in decision making about property, thus they will focus on what makes profit now, not what is best for the ecosystem. Human managerial skills are less than perfect, so even when they try to do the right thing they might very well do the wrong thing for the ecosystem and themselves. Environmentalism Humans must live in the environment. Thus, the large changes that occur in the environment due to human activities are accepted but damage to the environment must be corrected in the interests of first humans and second the environment. When there is environmental damage that threatens human health it must be cleaned up as well as prevented in the future. This is the paradigm accepted by most current governments – when there is an environmental problem and public opinion rises to do something about it, then there should be action. The focus is almost always on dealing with environmental problems after they arise. Arguments against this approach include: Neglects the value of prevention Much environmental damage cannot be cleaned up. Not everything is reversible. Actions are taken when human interests are at stake, not for the interests of the ecosystem. Environmental effects that do not concern humans (habitat loss, loss of genetic diversity, etc.) are not considered. Action tends not to be taken for multinational effects, where pollution that flows away from you is not seen as being a serious problem. Shallow Ecology The focus here is individual responsibility and changing lifestyles. Consumers are encouraged to “go green” by recycling, using eco-friendly products, driving less, etc. Educating consumers and citizens is key to changing society as people change their lifestyles. Arguments against this approach include: Many eco-friendly products are only slightly so or not really. Marketing with “eco” themes is full of over claims. Industrial and productive processes are hidden in this approach; yet continue to create vast environmental problems. A small action by consumers demobilizes them for more serious ecological action as they think they have done enough. There is no sense of correcting previous ecological harms, but only on changing future behaviors. Allows people to continue with a consumerist mindset that still has them using too many products and resources; it is just that they have a green label. Real need is to live on less. Deep Ecology THE EIGHT TENETS OF DEEP ECOLOGY (As established by Norwegian Philosopher Arne Naess and George Sessions in 1986) 1) The well being and flourishing of human and non-human life on Earth have value in themselves (synonyms: intrinsic value, inherent worth.) These values are independent of the usefulness of the non-human world for human purposes. 2) Richness and diversity of life forms contribute to the realization of these values and are also values in themselves. 3) Humans have no right to reduce this richness and diversity except to satisfy vital needs. 4) The flourishing of human life and cultures is compatible with a substantially smaller human population. The flourishing of non-human life requires a smaller human population. 5) Present human interference with the non-human world is excessive, and the situation is rapidly worsening. 6) Policies must therefore be changed. These policies effect basic economic, technological, and ideological structures. The resulting state of affairs will be deeply different from the present. 7) The ideological change will be mainly that of appreciating life quality (dwelling in situations of inherent value) rather than adhering to an increasingly higher (economic) standard of living. There will be a profound awareness of the difference between bigness and greatness. 8) Those who subscribe to the foregoing points have an obligation (ethical imperative*) directly or indirectly to try to implement the necessary changes. (I would also agree with Arnae Naess that adherence to any of the above must come from the heart and not out of obligation.*) Arguments against this approach include: It is entirely natural for humans to put their values first. Changing that will be virtually impossible. Many creatures change the environment and their part of it, so humans do what animals already do. This approach requires vast declines in population, and that can only happen with serious mass killings or massive deprivations of liberties. This sounds great for those already well off, but for the poor of the earth this call for frugality on the part of citizens of Europe, for example, seems very selfcentered. This approach tends to romanticize primitive lifestyles from earlier centuries, and “things never were as good as they used to be.” It seems to ignore the important role that technology will play in any human future. Is technology always anti-ecology? Defensive Deep Ecology Humans are a virus that infests planet Earth. The only way to cure that is to get rid of humans. Then, the world can heal and move on to become something better. Human extinction would be good and, in fact, is the only way to save the earth.