hbr_gaming_17dec

advertisement

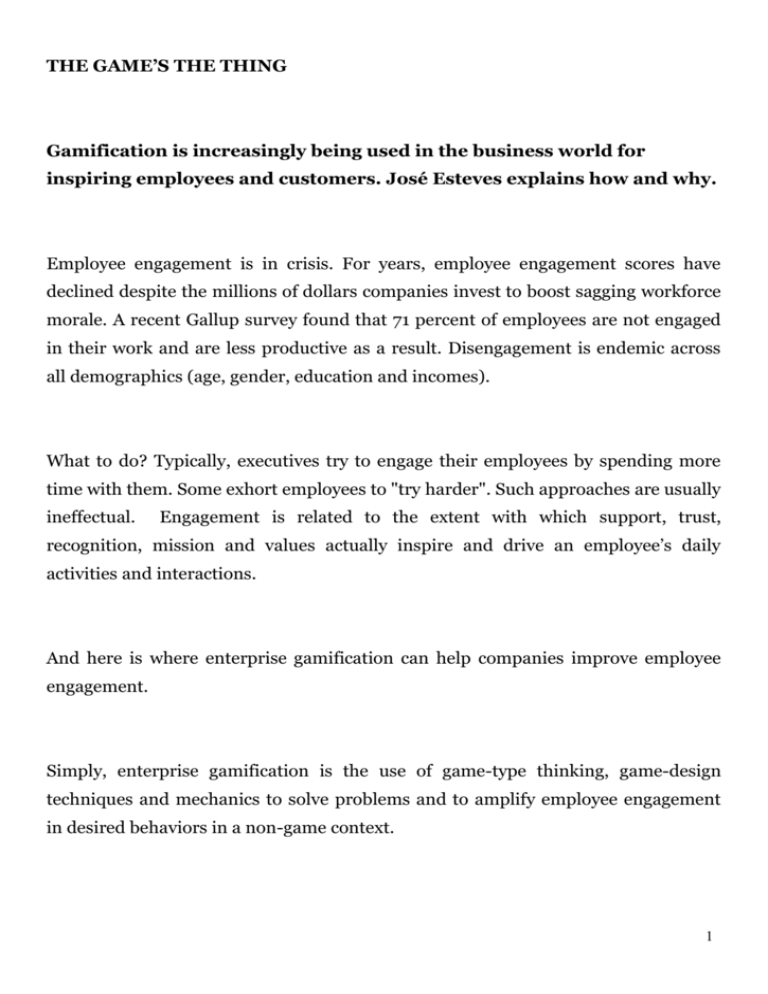

THE GAME’S THE THING Gamification is increasingly being used in the business world for inspiring employees and customers. José Esteves explains how and why. Employee engagement is in crisis. For years, employee engagement scores have declined despite the millions of dollars companies invest to boost sagging workforce morale. A recent Gallup survey found that 71 percent of employees are not engaged in their work and are less productive as a result. Disengagement is endemic across all demographics (age, gender, education and incomes). What to do? Typically, executives try to engage their employees by spending more time with them. Some exhort employees to "try harder". Such approaches are usually ineffectual. Engagement is related to the extent with which support, trust, recognition, mission and values actually inspire and drive an employee’s daily activities and interactions. And here is where enterprise gamification can help companies improve employee engagement. Simply, enterprise gamification is the use of game-type thinking, game-design techniques and mechanics to solve problems and to amplify employee engagement in desired behaviors in a non-game context. 1 Playing the Game For some the very thought of social gaming is anathema to a working environment. But, there is an important difference between “playing” and “gaming”: while playing is mainly an entertaining activity which relates simply to having fun, gaming attempts to achieve a set of goals. Thus, games should not be play; yet don’t let that imply they do not require play. For executive skeptics, it is worth noting that game dynamics have long been used to inspire performance and engagement among employees, salespeople, as well as among customer service representatives, partners and suppliers. In reality the workplace is already filled with games and game elements (levelling up, badges, leaderboards): think of employee of the month, selling compensation mechanisms, annual bonuses or career development plans. But most of these examples are merely incentive systems based on extrinsic rewards that work very well for a short period. In contrast, gamification focuses on intrinsic motivations, which arise from within – doing something because you want to. With new technologies such as social media, mobile technology and geolocation, gamification can be designed in a way to be more interactive, more collaborative, more real-time and dynamic. And it works. Firms like IBM are getting a return on their investment by gamifying some of their business activities. In order to reduce the costs of internal projects, IBM’s Social Laboratory gamified its documentation translation process by awarding points to employees who helped translate documents. The best employees used points to earn money for their charities. The results were improved accuracy, reduced internal project time and reduced costs – IBM saved millions in translation 2 costs. But through this process, IBM did much more: it made employees better motivated and happier from their successful performance. Good Gaming Practice So, what is good practice for using games? And how can we best design the games we play in the workplace? Our research analyzed how 21 firms used gamification. We found that gamification has moved from simply promoting competition, using rewards and compensation management, to become a much more sophisticated and subtle tool implemented to influence and change the behavior of employees. Here are three ways in which firms can learn from the gamification activities of successful companies: 1. Expanding Symbolic Capital Monetary rewards are easy to implement but they are far less meaningful or memorable. Instead, enterprise gamification focuses on non-monetary rewards and it is framed as a process delivering status symbolic prizes for the employees. Status and recognition are important motivators to invigorate employee engagement. The French sociologist, Pierre Bourdieu defined these status symbols as symbolic capital, the way a person is known and recognized and the embodiment of: standing, good name, honour, fame, prestige and reputation. But status is only rewarding when others are aware of it. Thus, it is important to use gaming techniques that create opportunities for status conveyance. 3 SAP decided to build a contributor recognition program within the SAP community network (SCN), an online social network of over 2.5 million SAP professionals. The aim was to encourage a spirit of collaboration, knowledge sharing and networking. SCN is a pure example of symbolic capital implementation in a business context by using some game mechanics (points, status levels, badges and leaderboards). The contributor recognition program allows users to earn community points for every contribution they make, which then becomes an indicator of status in the SCN community. Different types of contributions (answer questions, blog posts, wiki contributions, e-learning videos) receive different number of points. Additional points are received when community members recognize the value of contributions by using “Like,” “Rate,” and “Share” features. These feedback points attempt to motivate contributors to provide content that is useful for the community. SCN uses different badges that indicate the different levels of Active Contributors (Bronze, Silver, Gold, and Platinum). Users only need 250 points to reach the initial level of Bronze Active Contributor, but then they need to work hard to gain recognition as a Top Contributor in their field of expertise. The ultimate goal is to get a high reputation and prestige on the SCN site increasing contributor’s community visibility which can positively impact contributor’s career. For example, recruiters and hiring managers are looking for SCN points on resumes, to screen applicants and interviewing those candidates first. SCN scores are also tallied by field of expertise. Anyone who has played competitive sport will recognize the power of local leaderboards. Having local league tables gives you a chance to shine against your immediate competition. If contributors are part of their company’s team then, their individual points are aggregated into the company score, and SAP publishes a leaderboard of top 4 companies participating on SCN to drive competition between companies. SAP customers and partners looking for SAP experts use individual and company rankings on SCN to determine who they should talk to. This SCN score impact had a sided effect on employee evaluation systems. Some companies to engage their employees on SCN are adding SCN points to employee’s performance evaluation. SCN gamification also promotes advocacy engagement enhancing participants’ knowledge and skills through active sharing of ideas and experiences, and improving users writing ability. SAP measures SCN success by monitoring the member’s level of engagement and the quality of that engagement. SCN has more than 1,2 million unique visitors per month, 3,000 discussion posts per day and 375 different topic categories. Reinforcement - Badges are another way to improve symbolic capital. Creating a badge lets people creatively recognize successes in their own words. Badges then have a shared meaning, creating trusted indicators of achievement which increase employee’s symbolic capital. Some studies show that a combination of highprobability small rewards, with a low-probability large rewards satisfy both the skeptical and optimistic sides of the brain. You get frequent periodic reinforcement coupled with the lottery-like chance of big winnings. Ford’s Profession Performance Program (P2P) is a very good example of reinforcement elements. The overall theme for the game mechanics was the Ford Cup, a race to the finish and the score was measured in racing performance measurements. Participants actually competed with learning. Each “garage” had a “trophy case” where participants could show off the badges they earned. Employees earned a badge for performing a variety of actions: watch an e-learning material, watch a video, participate in a discussion 5 forum. Badges were aligned to specific business goals. The success of the program has resulted in increased behaviour to engage in informal learning. The game is continuously evolving: as business goals change, so do badges. By modifying the game over time, a culture of continuous engagement is created which keeps the game sustainable, fresh and new Different levels, different engagement – on many occasions, the prizes, gift cards and badges are simply not enough. Sometimes players just want to participate, learn and improve some skills. Game levels therefore establish a sense of progress. By accepting that players will be at varying stages at any given time, a company can show the depth of mastery people have achieved pertaining to a certain skill or a process. Playing games that are too difficult is not fun. But playing games that are too easy is not fun either. The key aspect here is to design different levels that provide achievable goals and lead the player to engage in more activities so he or she can eventually move on to the next level. Also we can consider two levels of engagement: the individual level, which usual entails self-exploration and selfexpression, and the social interaction level which fosters collaboration and cooperation. Sometimes gaming processes combine both. Many companies are still struggling to develop effective intranets that engage employees. One solution may be gamifying their intranets by using Jive, a social intranet platform which combines social interaction and gamification features, such as role-based missions, team-based goals and competitions, status levels and badges, real-time feedback and rewards, and integration with collaboration tools. Jive allows the tracking dozens of employee actions including document creation and editing, content sharing, search capabilities, recommendations and control levels for security, privacy, permissions and compliance. Employees can collaborate at every level: team, departmental and cross-organizational. Jive offers quick and easy 6 onboarding challenges for new community members and then the opportunity to design different game levels for encouraging Jive usage and mastery. Feedback/Juiciness - Feedback is an elemental and constant mechanism in gamification. It is what informs players that they have done the right thing and/or provides information that helps them thoroughly learn the content. By using realtime feedback, companies can ensure that a player knows his or her progress toward the goal, the amount of life or energy left, location, time remaining, stuff collected and even how other players are doing. Also, the game can be programmed to provide alerts regarding the possible impact of their next actions. An excellent way to increase symbolic capital is by amplifying positive behaviors that already exist by using juicy feedback mechanisms. A “juicy feedback” occurs when a small action produces a surprisingly large reaction. Simple things like giving others thanks for meaningful achievements, help, etc. are efficient ways to increase recognition and thus increase motivation. A business problem that enterprise gamification can improve is employee performance management. High-performing companies such as Facebook, Spotify, Linkedin and GLT Group are using Salesforce Rypple, a web-based social performance platform that allows employees to create and compete in challenges, receive real-time feedback and recognition from co-workers, see what others are working on, and find where needed skills may exist within an organization. Rypple is not a game, but it was developed with several game design principles in mind to foster intrinsic motivations 2. Focusing on Intrinsic Motivations The sense of fun in gaming is the fuel for intrinsic motivations – experiences of 7 competence, self-efficacy, mastery, recognition and social status rather than monetary reward. This is what drives profound commitment and sense of ownership needed for a truly engaged and innovative workforce. Lack of motivation is one of the main reasons for the failure in adopting some business tools like CRM. Although the adoption of CRM applications has been shown to dramatically enhance sales performance and increase company revenue, sales people still frequently resist incorporating these tools into their everyday work tasks. Bunchball, a leading provider of gamification tools, has created Nitro Flamethrower which can be used with the CRM system, salesforce.com. Nitro is embedded in the sales force automation system. It improves data quality and speeds-up data entry -- very often a source of conflict between sales representatives and their managers. For example, Nitro can be set up so that every closed sale awards a salesperson 500 points. The salesperson can then examine their points total and the rewards others have received. Regional or workgroup competitions between teams can also be used. Nitro helps to improve the sense of meaningfulness to work outcomes, sense of competence, and relatedness (feeling connected with others and having a sense of belonging at both the individual and the community level) to build strong intrinsic motivations and to engage employees. 3. Enhancing Eudaimonia Enterprise gamification helps employees accomplishing aspirational goals which keeps people motivated and focused. Aspirational goals also promote Eudaimonia, a Greek word describing a state in which an individual experiences happiness by successfully performing their moral duties. IBM document translation gamification 8 is a good example of promoting eudaimonia. Elsewhere, based on an eudaimonic model, SAP employees play a game that encourages carpooling. Employees gain points by entering information that matches carpooling partners. The benefits are multiple - the game takes cars off the road while building employee social ties, and SAP saves money since many of the vehicles are firm cars. Looking at the Dark Side Enterprise gamification may seem like employee engagement wonderland but there are drawbacks. Besides the typical issues of time involvement, gamification can be perceived as a new form of control and pressure which is known as exploitationware. For example, leader boards are an efficient way to foster recognition but, depending on the context, leader boards can be viewed as another form of control and pressure because they can impact employee reputation, popularity, and credibility. The usage of leader boards might in fact hinder sales people not because of the engagement of the game but because of social pressure to continuing playing the game – there is pressure because the employee knows that if he or she stops playing the game, it will impact their reputation. Leader boards and other game mechanics that are associated with the pressure to “show off” symbols, is simply the need for preserving one’s status quo which can have a negative effect on employee behavior. Some game dynamics cause a huge pressure on users to continuously accept requests or involve them in a set of activities which demand a lot of time and dedication. Thus, a poorly designed gamification strategy can unfortunately entangle users in a web of social obligations, creating social pressure which is another form of symbolic violence with an unnoticed sense of domination. The other problem is that gamified applications “pointsification” aren’t necessarily fun. Some of them are simple processes that aren’t necessarily reinforcing behavioral improvements. On the contrary, they may promote cheating to earn points easily. It 9 is important not to fall into the trap of rewarding employees too easily or excessively without a meaningful reason. Finally, it is important that enterprise gamification solutions must be scaled along a time frame -- games must be kept fresh or engagement will drop. José Esteves (jose.esteves@ie.edu) is Professor of Information Systems at IE business school, Madrid, where he has been based since 2004. He received his Ph.D. in Information Systems from the Universidad Politécnica de Catalunya, Barcelona, and degrees in Information Systems from Universidade do Minho, Portugal, and a Diploma in Business Administration from Instituto Superior de Tecnología Empresarial, Porto, Portugal. He is one of Europe’s foremost experts on the impact of technology on organizations. ends 10