Regulation Impact Statement: Limited Merits Review of Decision

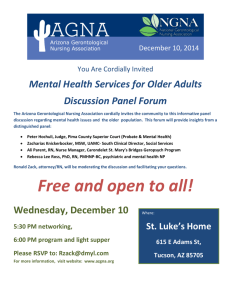

advertisement