Patterns of Innovation in the Okanagan Wine

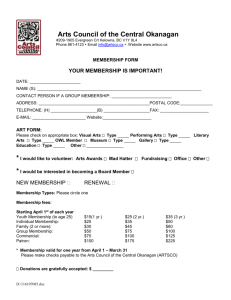

advertisement