Position statement example - University of East London

advertisement

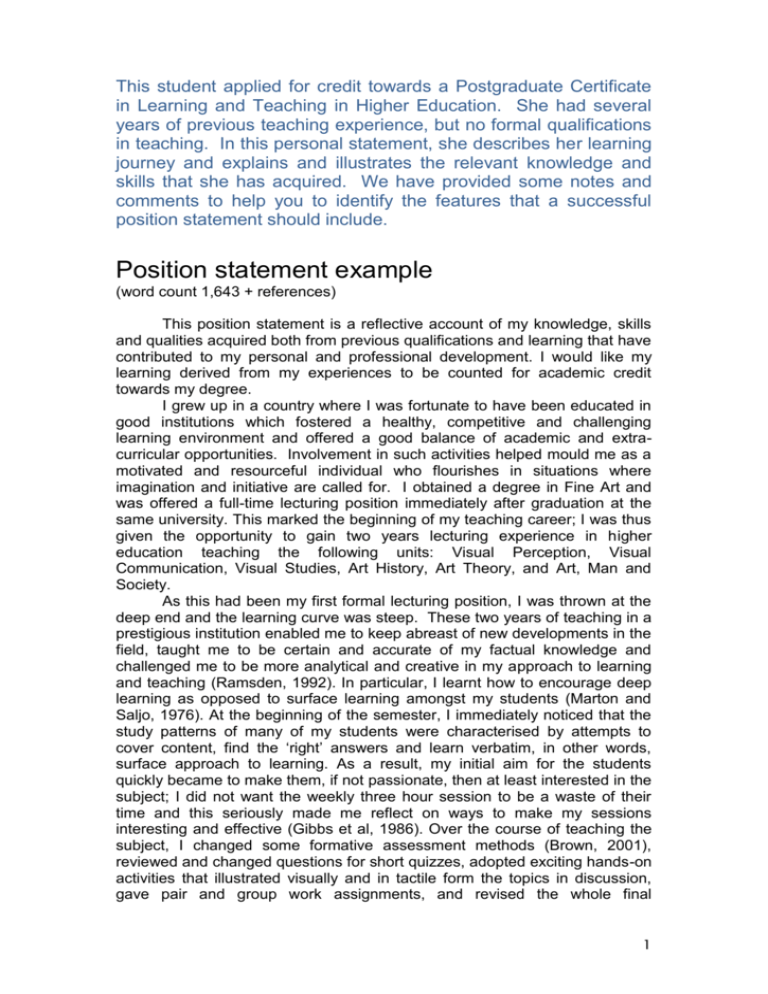

This student applied for credit towards a Postgraduate Certificate in Learning and Teaching in Higher Education. She had several years of previous teaching experience, but no formal qualifications in teaching. In this personal statement, she describes her learning journey and explains and illustrates the relevant knowledge and skills that she has acquired. We have provided some notes and comments to help you to identify the features that a successful position statement should include. Position statement example (word count 1,643 + references) This position statement is a reflective account of my knowledge, skills and qualities acquired both from previous qualifications and learning that have contributed to my personal and professional development. I would like my learning derived from my experiences to be counted for academic credit towards my degree. I grew up in a country where I was fortunate to have been educated in good institutions which fostered a healthy, competitive and challenging learning environment and offered a good balance of academic and extracurricular opportunities. Involvement in such activities helped mould me as a motivated and resourceful individual who flourishes in situations where imagination and initiative are called for. I obtained a degree in Fine Art and was offered a full-time lecturing position immediately after graduation at the same university. This marked the beginning of my teaching career; I was thus given the opportunity to gain two years lecturing experience in higher education teaching the following units: Visual Perception, Visual Communication, Visual Studies, Art History, Art Theory, and Art, Man and Society. As this had been my first formal lecturing position, I was thrown at the deep end and the learning curve was steep. These two years of teaching in a prestigious institution enabled me to keep abreast of new developments in the field, taught me to be certain and accurate of my factual knowledge and challenged me to be more analytical and creative in my approach to learning and teaching (Ramsden, 1992). In particular, I learnt how to encourage deep learning as opposed to surface learning amongst my students (Marton and Saljo, 1976). At the beginning of the semester, I immediately noticed that the study patterns of many of my students were characterised by attempts to cover content, find the ‘right’ answers and learn verbatim, in other words, surface approach to learning. As a result, my initial aim for the students quickly became to make them, if not passionate, then at least interested in the subject; I did not want the weekly three hour session to be a waste of their time and this seriously made me reflect on ways to make my sessions interesting and effective (Gibbs et al, 1986). Over the course of teaching the subject, I changed some formative assessment methods (Brown, 2001), reviewed and changed questions for short quizzes, adopted exciting hands-on activities that illustrated visually and in tactile form the topics in discussion, gave pair and group work assignments, and revised the whole final 1 examination paper, focusing on essay questions that sought to bring out students’ understanding of the topic. I strived to encourage the deep approach to learning where emphasis is on the subject’s relevance and application, rather than acquired facts, dates and names of movements they had memorised. The deep approach seeks to make sense of what is learnt, integrates knowledge and theoretical ideas to everyday experience, and is characterised by the relation of and reflection on previous knowledge to new knowledge. It is meaning-orientated; its aims include enhancing students’ abilities to use their powers of imagination, to be flexible, to adapt and transfer skills, and to use this understanding in creative ways that are relevant to their lives outside the academic environment (Marton and Saljo, 1976). As a direct consequence, learning became fun and holistic (Jacques, 2000) and student interest generally soared; many students achieved higher grades than originally expected. In 1991, I moved to England and started a Masters in Fine Art. I was faced with a completely different system of Higher Education compared to that which I had been accustomed. I therefore had to learn and understand this new framework of thinking and the education system. The theoretical discussions and debates I encountered at this level of education made me reevaluate my approach to learning. At this level of learning, I was able to practise and improve my ability to communicate articulately, concisely and clearly and learnt to put across my lessons well. I found that good communication skills involve the ability to connect with the students in such a way that makes the tutor aware of the students’ varying levels of comprehension. I was also challenged to review my own teaching methodology and adopt new practices as appropriate in order to meet students’ learning needs (Gosling, 2003). The right context for this arose when I was given a choice of electives on the Masters. I embarked on a mentoring project in Life Drawing where I was given the chance to observe students’ learning styles and needs as well as teach sessions within the module. My involvement in this project gave me a more astute and keen sense of the teaching practice. I was reminded how vital it is for tutors to be aware that students start from a level specific to their previous experience and background and their learning progress is contingent upon how the structure of the module is channelled effectively towards the learner’s development (Boud, 1989). In this particular context, I discovered that a one-to-one approach is crucial to student progress. This enables the tutor to gain more insight into the level of the student’s knowledge and struggles, technical and otherwise, which affect their ability to grasp concepts and make real progress. I believe that encouraging students to assess their progress regularly develops their critical and practical skills as well as cultivates vicarious learning. I implemented this approach on the mentoring project by giving the students exercises that promoted self-assessment such as writing down, addressing and finding solutions to the problems they encounter. Critically assessing their own work during the various stages of the working process and questioning whether they are applying theoretical learning in a more innovative, speculative and investigative manner instead of a mere application of formulae. Also interacting with other students to discuss measures of progress. 2 In teaching, I make it my goal to draw out ideas from the students instead of ‘spoon-feeding’ them. I endeavour to ask pertinent questions and introduce activities geared towards reflective learning (Moon, 2001), learning by practical application (Kolb, 1984) and learning by self-realisation. Students need regular motivation. I find the use of creative visual aids, for example, the use of MS Power Point in appropriate lectures, helpful for students to retain facts and details. Small group discussions (Jacques, 2000) and workshops (Brookes-Harris & Stock-Ward, 1999) provide a more effective atmosphere in learning and encouraging student participation especially amongst the quiet and shy ones. Collaboration and team activities make the subject more interesting and help in sustaining students’ attention. A milieu that provides opportunities for students to participate and get involved is paramount in the process of learning. Whilst on the Masters, I applied for a part-time position in assisting lecturers at my University and was offered the post which was to support the university’s Dyslexia coordinator. This position introduced me to university academic and administrative work pertinent to student development such as the Year One Experience and student retention. Subsequent to this, I was offered more work, this time working for the Learning Development Unit and learnt more about widening access and participation initiatives and student recruitment. Shortly thereafter, I was offered an advisory post in this unit and thus my involvement in student support and advice began. I was trained on the job, shadowing the Senior Adviser at many opportunities, and began liaising with various members of staff across the university. Not long after this, the senior adviser left the University for a position in another higher education institution and I was offered his position as a result. This position which I still hold currently has catapulted me into yet another steep learning curve. I had to learn to work systematically and independently as well as contribute actively as part of a team. I had to motivate myself and set my own aims and targets and meet them. Additionally I needed to initiate meetings and staff development with other members of staff and to think of creative ways of developing new ideas and designing new methods of teaching delivery. Within a unique milieu where social and cultural diversity plays a prominent factor in determining students’ learning needs, my teaching experience has taught me to be more sensitive and able to adjust to the varying levels and nature of students’ needs without sacrificing the quality and standard of my work. In all the above learning experiences in teaching, I have encouraged personal and professional development in my students where they learn to reflect and undertake self-assessment of their knowledge, skills and achievements, where the opportunity to present what they have learnt and as a result demonstrate what they can contribute to their present environment is promoted, and where they are given the freedom to set their own learning aims and professional career goals (Wailey & Simpson, 2000). Having advised and supported numerous mature students from diverse socio-cultural backgrounds coming in with an assortment of learning needs and learning styles, I am more convinced and persuaded that personal and professional development is at the heart of lifelong learning (Bailie & O’Hagan, 2000). In light of this, I would like to engage more fully in teaching personal and professional development and reflective practice and increase my 3 involvement in these processes within art-based programmes in Higher Education. For my own personal and professional development, I believe that obtaining a Postgraduate Certificate in Learning and Teaching in Higher Education will foster understanding of theoretical knowledge and acquisition of its practical application in the above-mentioned contexts and will be a crucial stepping stone in furthering my career in teaching. Writing this position statement has given me the opportunity to review my previous learning and assess its relevance to my present position in life. This process has in itself been a learning experience for me. I have presented learning outcomes derived from my experiences that I would like to be counted for academic credits towards my degree programme. References: Bailie S. & O’Hagan C. (2000). APEL and Lifelong Learning. Belfast: University of Ulster Boud, D. (1989). Some Competing Traditions in Experiential Learning. In: W.W. McGill, ed. Making Sense of Experiential Learning: Diversity in Theory and Practice. Buckingham: SRHE and Open University Press. Brooks-Harris J. & Stock-Ward S. (1999). Workshops: Designing and Facilitating Experiential Learning. London: Sage Publications. Brown, G. (2001). Assessment: a guide for lecturers. York: LTSN Generic Centre Assessment Series 3 Gosling, D. (2003). Supporting student learning. In: H. FRY et al, eds. A handbook for teaching and learning in higher education: enhancing academic practice. London: Kogan Page Jacques, D. (2000). Learning in Groups. 3rd ed. London: Kogan Page Kolb, D. (1984). Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall. Marton, F. & Saljo, F. (1976). On qualitative differences in learning – 2: Outcome as a function of the learner’s conception of the task. British Journal of Educational Psychology. Vol. 46(2) 115-127 Moon, J. (1999). Reflection in Learning and Professional Development. London: Kogan Page Ramsden, P. (1992). Learning to Teach in Higher Education. Kent: Routledge. Wailey, T. & Simpson, R. (2000). Walking not falling – waving not drowning – dancing not stumbling: Managing guidance in higher education. In: D. O’Reilly, ed. Research and Innovation in Learning and Teaching. London: University of East London. 4 COMMENTS This position statement gives a very strong sense of the writer’s personal journey through education, work and professional development – she tells us very clearly what she has learned through her past experiences, what she is doing now, and what she hopes to achieve in the future. The writer’s description of her own career serves as a model of continuing professional development. Her career never seems to ‘stand still’, as she is constantly reflecting on her work, developing her practice, and encountering new learning situations. In a way, her learning seems to proceed in cycles. When she takes on a new challenge she reflects carefully on how to develop new techniques and methods in order to improve her practice. These efforts bring about improvements, both in her own performance and in that of the people she works with. Then, when the writer takes on a new challenge, such as studying for a new qualification or starting a new job role, the cycle of learning, reflection, thinking and action start all over again. It is interesting that the writer describes how she developed activities for her students to encourage reflective and experiential learning. She references an influential book by David A. Kolb, Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development (1984), which describes learning through experience as a kind of cycle in which experience, reflection and ideas feed into one another. This is indeed a useful concept for students wishing to apply for AEL! You may find it useful to look at this book before writing your own position statement. Kolb’s Experiential Learning Cycle. (Illustration from www.learning-theories.com) 5