Pam_Thompson_Paper - Higher Education Academy

advertisement

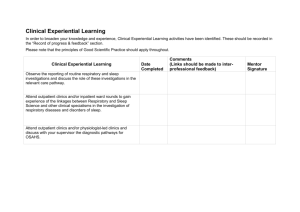

The Challenge of Integration-Conceptual Models for Inclusive Practice Rachel Higdon; Pam Thompson De Montfort University, UK pthompson@dmu.ac.uk rhigdon@dmu.ac.uk Abstract. “There is nothing so practical as a good theory” Lewin (1951:169). This paper interrogates the integration of theory and practice, particularly in those areas of Higher Education where studying for a degree at undergraduate and/or post-graduate levels involves both classroom and work-based study and the necessity of reconciling higherlevel academic learning with high levels of competency of practice. The paper proposes some ways forward whereby, using innovative models, academics teaching on programmes which lead to employment in a profession can ensure that learners are involved in high quality experiential learning that makes them able and ready to “do” their professional practice. In doing this, and accepting the idea that, experiential learning is a continual interaction of theory and practice where each informs the other, it proposes that, ultimately, in HE institutions, a collaborative, interdisciplinary approach may be the best way forward for practitioners to develop and share models which can be the starting point for their own learners to develop their own. The paper presents a brief overview of some of the existing theories of experiential learning and models employed therein including Kolb’s learning cycle and Schon’s “reflective practitioner”. It then considers a case-study from a specific programme in relation to the actual teaching of theory in relation to practice with a view to examining whether these, or other models are being applied, and to what purpose. It concludes by suggesting ways in which practitioners might review their current academic practice and create new conceptual models (ideally, in the light of collaborative, inter-disciplinary dialogue) to integrate policy, theory and practice in ways that make better sense to the learner. 1. INTRODUCTION “Work-based learning’ is arguably a complex, contested term” (HEA, 2006:3 [1], HEFCE, 2006[2]; Brennan and Little, 2006 [3], QAA, 2007 [4] in Williams et al., 2008:1) [5] presumably because of its wide-ranging nature and contested sites of responsibility for learning. The Leitch Report (2006:21) [6] (cited in Williams et al 2008:1) [5] places an emphasis on employers working closely with HEIs and asserts that “work-based learning provides a powerful learning environment for higher order enquiry skills and capabilities demanded by the UK economy in an increasingly competitive globalised environment”. (Moreland, 2004[7] in Williams et al., 2008:1)[5] Furthermore, “higher education programmes must progressively confront students with complex, inthe-world activities that encourage self-reflection and risk assessment”. These assertions could be taken as an amalgam of some of the components of what researchers have widely considered as effective experiential learning: learning which is situated, active, reflectivein–action, and, therefore, effectively experiential, as is evidenced in examples and case-studies from practitioners on such programmes at this university. For the purpose of this paper, by “work-based learning”, we are referring to some programmes in health and social-science based professions e.g. social work, speech therapy, youth and community work where placements are not an option but an integral part of the learning and delivery is not only by academics but from professionals in the related field. Such programmes, by their nature and avowed professional ends, require students to wrestle with and try to reconcile high academic learning with the requirements of competent practice. Practitioners on both side of the divide need ways to collaborate for their own development and to make the best learning happen for students. The inter-disciplinary nature of the PGCertHE group at this university has proved a fertile site for discussing how to reconcile theory with practice, or, put in another way, the types of learning students need to obtain such a professional qualification. The case-study here, one of several, arose from session discussions, content of projects and assignments and interviews with relevant staff. “Interprofessionality”, as defined by d’Amour and Oandasan (2005:10)[8], is “ an education and practice, an approach to care and education where educators and practitioners collaborate synergistically”. ( Colyer et al., 2005:14) [9] While these multi-disciplinary discussions do not denote an interprofessionality regarding curriculum design and overall degree structures, its literature is useful in attempting to understand the issues. THEORIES AND MODELS Learning theories are ideas about how and/or/why change occurs and models are some kind of representation of those theories whether it be in a diagram or in words. Are there any models, in the teaching and learning of such programmes which may be useful for students across disciplines in trying to make sense of what is learnt in the university and on placement and to assimilate that in a professional context? Kolb’s (1984 )[10] learning cycle is a familiar one in teaching and learning on the PGCertHE, also on Social Work, Speech and Language Therapy and Youth and Community Work degree programmes, with its emphasis on experience/reflection/conceptualization and application to new situations. The belief that definitions of work-based learning are problematic is espoused in the QAA in “Code of Practice for the Assurance of Academic Quality and Standards in Higher Education” which provides a “set of precepts with accompanying guidance on arrangements for work-based and /or placement learning”. (2007:4) [17]. It is concerned with arrangements made for identified and agreed learning that typically take place outside an HEI. The QAA literature seems to be suggesting that it the institution itself, in collaboration with its partners, that needs to draw up its own model with its own definitions after consulting wider literature. Whether this means institutional policy or practice at programme level is unclear: “Academic staff in departments and schools do not necessarily need to be familiar with the detail of all the various sections of the Code of Practice, although they might well be expected to be familiar with the institutional policies it informs and any parts which are particularly relevant to their own responsibilities” (2007:3)[18] Figure 1: Learning Cycle (Kolb:1984)[11]. Beard’s (2006) learning combination lock is a diagnostic tool which can be used to examine existing programmes and determine whether they cover the main elements of the learning process. Beard, in fact, considers the learning combination lock to be a “metamodel” underpinned by theories of perception and information-processing that “brings together all the main ingredients of the learning equation” in a series of movable tumblers encompassing the external environment (learning place, activities), sensors (senses/emotions) and internal environment (type of intelligence, ways of understanding). (Beard and Wilson, 2006, [12] Brant, 1998, [13] in Hartley et al 2005:3-7)[14]. Colyer et al (2005)[15] ask whether we should rely on borrowed theories ( and presumably, related models that aid their understanding) as educators and practitioners or whether we should be developing our own so as to draw in multiple aspects of the various contexts. Figure 2: The Learning Combination-Lock (Beard: 2002) [16] The framework – seems like the ingredients for the “season to taste” recipe. In the QAA Code of Practice identifying employers as key partners is explicit. This notion of an institution working with partners and making a personal recipe from suggested ingredients seems a popular one in the current British education and training system at all levels, from the introduction of new Diplomas in 14-19 learning so that learners can pick their best fit [19] to the introduction of foundation degrees [20] and an increase in institutions offering work-based programmes, to the “Train to Gain” government scheme of workplace training as part of an “upskilling” agenda [21]. This pick and mix model of learning seems only useful if it is genuinely relevant to the individual learner and is recognized as incomplete. As mentioned, Beard’s (2006) [22] learning combination lock appears to be also a model that practitioners can “pick” how best to support the learners to learn through the various combinations. It seems that to make the learning combination lock model work, the practitioner needs to design a further model from the combinations, to make it personal and relevant to their learners. S/he needs to decide which particular ingredients are needed to attain desired outcome/s. A personal model, therefore, seems the next step and this may be interrogated alone or achieved in collaboration. In reality how flexible and useful are these “pick and mix” models for individual learners? This kind of “pick and mix” model in the experience based learning arena seems to contradict much research that has espoused the need for a reflective or even scholarly model in this kind of learning. Researchers (Argyris and Schön, 1974 [23]; EXPERIENTIAL LEARNING Schön, 1983, [24]; Boud et al, 1985 [25] and Moon, 1999 [26]) have supported the need for reflective time by the learner and the need to review and critique one’s practice and look to improve it. 2. Moon (1999) encourages practitioners to reflect on their theory and practice through the use of a learning Journal “an accumulation of material that is mainly based on the writer’s process of refection”. (1999:4)[27]. Anderson, Boud and Cohen (1999) [32] go further in arguing that experience-based learning is based on a set of assumptions about such a type of learning: Argyris and Schön (1974) talk about the need for reflection to evaluate the success of a work based programme. Their theories of action highlight problems in models where both theory and practice seem to be embodied in the curriculum but are not necessarily being successfully integrated. Argyris and Schön argue that there is a split between the theory-in-use, those actions that practitioners really “do”, and “espoused theory”, those actions that they would like others to believe they do. Often the practitioner is not even aware that the “theory-in-use” is the course they will take in “real” practice. (Argyris and Schön, 1974: 6-7)[28] Helme (2005) in (Colyer et al., 2005:19-20) [29] develops such notions further in relation to institutional structures. She points out, particularly in relation to the relationship between theory and practice in interprofesssional education, that confused messages might be given out. “Because of the practical and conceptual logistical problems in aligning professional requirements and assessment criteria, programme requirements and learning outcomes, timetables and learning content across different combinations of professions and teaching teams, choices about how to provide interprofessional learning opportunities can be perceived as almost wholly driven by internal logistics and external compulsion.” (Colyer et al., 2005:19-20) [30] Arguably, such practical and logistical problems may be inherent within a single programme related to one profession reliant upon input from practitioners in the field, placement tutors, academics from other disciplines teaching certain modules (e.g. Law), and so on. The lecturers must try to make sense of this meaningfully as a holistic learning experience and communicate this to the student. Practitioners on professional programmes mentioned above at this university, and evident in our case-study below, were unanimous in support of reflective practice as an important bridging factor in attempting to bring together academic and work-based learning and therefore, is most effectively experiential. This, according to Beard and Wilson is “a continual interaction of theory and practice in which each informs the other” (2006:18) [31]. experience is the foundation of, and the stimulus for, learning learners actively experience learning is a holistic process learning is socially and culturally constructed learning is influenced by the socio-emotional context in which it occurs construct their own Boud, Cohen and Walker (1993) [33] cited in Foley, G. (1999:225) [34]. Arguably it is the last two considerations that are often absent in models of experience-based learning (certainly in Kolb’s cycle and the learning combination lock model), or perhaps are not far-reaching enough to express all dimensions of what a learner must undergo in an attempt to reconcile requirements of academic and work-based/aspirant professional. There is an acknowledgement akin to Beard and Wilson’s [35] that learning involves the whole person: that the emotional dimension is as important as the cognitive and affective. However, Andreson et al. consider that what learners bring to the learning process, (whether it be a formal or informal recognition of prior learning ) and a particular ethical stance adopted towards learners by teachers, trainers, leaders or facilitators, are also necessary before an educational event can be properly termed “experiential”, and by definition, meaningful for the learner. (1999:226) [36] Brah and Hoy (1989:73) [37] argue that the fact that experiential learning has become something of an ideology in education is problematic. Jarvis et al., (1983:53) [38] Eraut (1994:1) [39] taking on ideas espoused by Johnson (1972:4) [40], (1984:17-25) [41] readily accepts the notion of treating the term, “professionalism” as an ideology, in order to denote the true status of individual professions. A definition of ‘ideology as ‘visionary theorising’ [42] seems attractive, if vague, yet somehow appropriate to various takes on experiential learning. Maybe we can extend this to be ‘visionary and visual theorising’ with the concomitant notion that theories, and so models, are best and meaningful only if made practical and with acknowledged ethical and value-driven dimensions. 4. CASE-STUDY This case-study is from a Speech and Language Therapy programme. It highlights ways that students have been encouraged to reflect on knowledge and experience in both academic, placement (and wider) contexts and how they have been facilitated in the bringing together of important learning from these areas. This lecturer moved from practicing within their profession into Higher Education teaching. The lecturer worked as a speech and language therapist in the NHS before moving into university teaching. She acknowledges that her role of therapy facilitator with its theoretical knowledge of counseling therapy and health psychology is not separate from her role of lecturer and a rich resource when used “consciously and professionally” to enhance the learning experience of students. She further recognizes the central role that placements play for speech and language therapy (SALT) students in training competent clinicians. These provided opportunities for students to apply theory to practice and to experience the challenges and advantages of working with service-users and multi-disciplinary teams. However, she also acknowledges that, in today’s rapidly changing NHS, the need to provide placement opportunities for a number of students may be seen by some providers to be an added pressure on limited resources, hence the imperative for HEIs to develop new models of practice-based learning. the placement was through the placement educator and the teachers felt that this was a more successful way of setting it up than if they had been approached directly by the university. Each placement was preceded by an orientation workshop held at the university. The students also had a meeting with their placement educators prior to the start of the placement. All the students had been introduced to the ideas proposed by Kolb (1984) [43] regarding cycles of learning. They were therefore familiar with the concept of practice sometimes occurring before theory or observation. (Parker and Emanuel 2001) [44]. The lecturer’s own model encapsulates very well the stages of learning moving from being a student to being a clinician in practice. It allows for intra-- and extra-personal skills and knowledge development and is driven by positive values. Such a model would provide a transportable site for discussions and negotiations between university and placement. As the lecturer notes, it “allows for experiences of independent creative problem-solving, instead of relying more heavily on feedback from supervisors” also that ”sensitive, well-structured peer feedback can have a profound effect on students’ selfesteem and on feelings of self-efficacy and Confidence”. Plummer (2004) [45] in Plummer (2008) [46]. Along with colleagues in the speech and language therapy department, the lecturer was involved in one of several national pilot projects to investigate the possible working of such new models. As she notes of these, ‘”whatever form they take, the main focus should be on collaborative practice between service providers”. The project mentioned here was piloted in the children’s speech and language therapy service. Here, four students at this post-1992 university (two second years and two fourth years) took part in a school-based project at a unit for children with moderate learning difficulties. The students attended for one day a week and stayed for the whole day. A teaching assistant acted as a link person so that any queries went directly to her. The fourth years “mentored” the second years and gave feedback on their progress to the placement educator (clinician). The lecturer mentioned that peer mentoring by fourth year students has been a successful element the university placements for some years but has not been used for a group project before. The placement educator visited the unit three times during this period and observed the four students running groups and carrying out work with individual children. As well as informing parents of the project, it was vital to involve teachers at the unit as early as possible so that this could be worked into the school’s annual development plan. Most of the preparation for Figure 3: From student to clinician: the practice-based learning continuum Plummer (2008) [47]. In concurrence with ideas expressed elsewhere here, the lecturer highlights the influence on this model of the idea of “legitimate peripheral participation” as proposed by Lave and Wenger (1991) [48] where professional training and learning from practice are viewed as inseparable. This is an enabling model where such learning is described as participative because it acknowledges that learning comes through doing. It is legitimate because all parties implicitly agree that unqualified people (in this case, students) are potential contributors to the “community of practice” and peripheral because they, (the students), are initially not directly involved with core activities (e.g. formal assessment and therapy) but will start with peripheral tasks and gradually build up their involvement with more central activities where appropriate. (Atherton, 2003 [49] in Plummer 2008:3) [50]. 3. CONCLUSION Higher Education Institutions, perhaps through the conduit of their academic research and development departments, or through their faculties can facilitate inter-disciplinary dialogue between academics working on these particular programmes where the fusion of theory, policy and practice is so crucial. Academics are supervising students not only in their learning but also in their practice; the outcome being independent practitioners ready and able to “do” once they leave the institution. Many of these work-based study programmes create professionals who will support vulnerable clients, for example in social work, probation, nursing, teaching or youth work and therefore have ethical implications at every step of the way from the recruitment of new learners to their competence in practice. Programmes can be particularly problematic for learners when they comprise of modules taught from a range of departments within the Higher Education Institution and through support from outside agencies. Beard and Wilson’s (2006:15) [51] criticism of certain types of learning seems poignant here; “all too often theories of learning, education, training and development are developed in isolation from one another and thus there is no overall coherence”. To avoid this we need to find time for collaborative work and for reflection between colleagues involved in these complex areas to bring coherence. Working together they can devise a series of innovative models that are discipline specific or generic that can be developed to aid academics working with students in this kind of professional, theory-based practice Beard and Wilson define experiential learning “as the sense-making process of active engagement between the inner world of the person and the outer world of the environment”. (2006:2) [52] Their definition seems a relevant one for the learner immersed in work-based programmes. The inner world of each learner on the programmes will be different and how they perceive their outer world will be different again. Models that conceptualise the complex elements of the course for the learner to gain their understanding will be useful but these can be further developed by the students individually to become their own blueprints of their professional practice. In this way academics and learners can be supported to find Lewin’s (1951) [53] precious, elusive practical theory that makes sense of it all. REFERENCES 1. Higher Education Academy (2006) Work-based learning: illuminating the higher education landscape. KSA Partnership, June 2006 Available at: http://www.heacademy.ac.uk/research/WBL.pdf. 2. HEFCE (2006) Towards a strategy for workplace learning.Available at: http://www.hefce.ac.uk/Pubs/rdreports/2006/rd09 06/ 3. Brennan, J. and Little, B. (2006) Towards as Strategy for Workplace Learning: Report of a study to assist HEFCE in the development of a strategy for workplace learning. Centre for Higher Education Research and Information. London. 4. QAA (2007) Draft Code of Practice: Work-based and placement learning (section 9) Draft. 5. Williams, C., Tomkins, A., McEwen, L., Higson, H. .Mason O’Connor, K & Wang. (2008). HEA Conference, July 2008. 6. The Leitch Report (2006) Prosperity for all in the global economy: world class skills, Department of Education and Skills. 7. Moreland, N. (2004) Entrepreneurship and Higher education: an employability perspective, ESECT/LTSN, York. 8. D’Amour, D. and Oandasan, (2005) .I. Interprofessional Practice and Interprofessional Education Care 19 (Supplement 1 May 2005 Special Issue: Interprofessional Education for Collaboration Patient-Centred Care Canada as a Case Study, pp. 8-20) 9. Colyer, H, Helme, M. and Jones, (eds.) (2005) The Theory-Practice Relationship in Interprofessional Education, Occasional Paper No. 7, November 2005, London: Higher Education Academy, p.9. 10. Kolb, D. (1984) Experiential Learning: Experience as a Source of Learning and Development, Prentice Hall: New Jersey. 11. http://www.ic.polyu.edu.hk/oess/POSH/Student/Le arn/tut15a.gif [Online] Accessed: 19 September 2008. 12. Beard, C. and Wilson, J (2006), Beard, C. & Wilson, J. (2006) Experiential Learning (2nd edition), Kogan Page: London pp. 3-9 13. Brant, L (1998) ‘Not Maslow again!’ A study of the theories and models that trainers choose as content on training courses, ‘MEd dissertation. University of Sheffield. 14. Hartley, P., Woods, and A., Pill, M. (2005) Enhancing Teaching in Higher Education, Routledge: London, New York, pp 3-5. 15. Helme, M. in Colyer, H, Helme, M. and Jones, (eds.) (2005) The Theory-Practice Relationship in Interprofessional Education, Occasional Paper No. 7, November 2005, London: Higher Education Academy, p.20. 34. Foley, G.(Ed) (1999), 2nd Edition, Understanding Adult Education and Training, Allen Unwin 16. Higher Education Academy (2008 http://www.engsc.ac.uk/resources/learning/experien tial.asp [On-line] Accessed: September 19th 2008. 35. Andreson, L., Boud D.,and Cohen, R. (1999) ‘Experienced Based Learning’, in Foley, G.(Ed.) (1999), 2nd Edition, Understanding Adult Education and Training, Allen Unwin, pp.226 17. http://www.qaa.ac.uk/academicinfrastructure/code OfPractice/section9/PlacementLearning.pdf 2007[on-line] Accessed: 12 September 2008. 18. http://www.qaa.ac.uk/academicinfrastructure/code OfPractice/section9/PlacementLearning.pdf 2007[on-line] Accessed: 12 September 2008. 19. http://www.dcsf.gov.uk/index.htm. 2008. [on-line] Accessed: 10 September 2008. 20. http://www.findfoundationdegree.co.uk/2008. [online] Accessed: 10 September 2008. 21. www.direct.gov.uk: (2008). [on-line] Accessed:10 September 2008. 22. Beard, C. & Wilson, J. (2006) Experiential Learning (second edition). Kogan Page: London pp 1-44. 23. Argyris, M. and Schön, D. (1974) Theory in Practice. Increasing professional effectiveness. Jossey – Boss: San Francisco. 24. Schön, D. (1983) The Reflective Practitioner. How professionals think in action. Temple Smith: London. 25. Boud, D. et al (eds.) (1985) Reflection. Turning experience into learning. Kogan Page: London. 26. Moon, J. (1999) Learning Journals. Kogan Page: London. 27. Moon, J. (1999) Learning Journals. Kogan Page: London pp 3-17. 28. Argyris, M. and Schön, D. (1974) Theory in Practice. Increasing professional effectiveness. Jossey – Boss: San Francisco pp 6-7. 29. .Colyer, H, Helme, M. and Jones, (eds.) (2005) The Theory-Practice Relationship in Interprofessional Education, Occasional Paper No. 7, November 2005, London: Higher Education Academy, p.14. 30. Colyer, H, Helme, M. and Jones, (eds.) (2005) The Theory-Practice Relationship in Interprofessional Education, Occasional Paper No. 7, November 2005, London: Higher Education Academy, p.14. 31. Beard, C. & Wilson, J. (2006) Experiential Learning (second edition). Kogan Page: London pp 1-32. 32. Andreson, L., Boud D.,and Cohen, R. (1999) ‘Experienced Based Learning’, in Foley, G.(Ed.) (1999), 2nd Edition, Understanding Adult Education and Training, Allen Unwin, pp.225 33. Boud, D. Cohen, R. & Walker, D. (1993) Using Experience for Learning. Open University Press: Buckingham 36. Beard, C. & Wilson, J. (2006) Experiential Learning (second edition). Kogan Page: London pp 1-32. 37. Brah, A. and Hoy, J. (1989) Experiential Learning: a new orthodoxy? in Making Sense of Experiential Learning, ed. Weill, S. and McGill, I., Society for Research into Higher Education and the Open University press: Buckingham, p.73 38. Jarvis, P., Holford., J. and Griffin, C. (2003), 2 nd Edition, The Theory and Practice of Learning, Kogan Page: London. p.53. 39. Eraut, M., (1994) Developing Professional Knowledge and Competence., Falmer Press: London. p. 1. 40. Johnson, T.J. (1972) Professions Power,Macmillan: London, p.4 and 41. Johnson, T.J. (1984) ‘Professionalism: Occupation or Ideology’ in Goodlaid, D. (Ed.) Education for the Professions: Quis Custodiet?, SRHE and NFER: Nelson, pp. 17-25. 42. http://www.merriamwebster.com/dictionary/ideology Accessed:12 September 2008. [On-line] 43. Kolb, D. (1984) Experiential Learning: Experience as a Source of Learning and Development, Prentice Hall: New Jersey. 44. Parker, A. and Emanuel, R. (2001) Active learning in service delivery: an approach to initial clinical placements. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders 33 (supplement), pp. 225-260. 45. Plummer, D. (2004), Helping Adolescents and Adults to Build Self-Esteem, Jessica Kingsley: London. 46. Plummer, D. (2008), unpublished paper, pp.1-3. 47. Plummer, D. (2008), unpublished paper, p.14. 48. Lave, J. and Wenger, E. (1991) Situated learning: legitimate peripheral participation, Cambridge: Cambridge University press cited in Atherton, J. S. (2005) Learning and Teaching: Situated Learning [On-line] UK: Available :http://wwwlearningandteaching.info/learning/situa ted.htm Accessed: 7 June 2008. 49. Atherton, J.S. (2003) Doceo: Competence, Proficiency and beyond On-line] UK: Available: http://www.doceo.co.uk/background/expertise.htm Accessed 7 June 2008. 50. Plummer, D. (2008), unpublished paper, p. 4. 51. Beard, C. & Wilson, J. (2006) Experiential Learning (2nd edition). Kogan Page: London p. 15 52. Beard, C. & Wilson, J. (2006) Experiential Learning, 2nd edition, London: Kogan Page, p.2 53. Lewin, K. (1951) Field theory in social science: Selected theoretical papers. Darwin Cartwright (Eds.) Harper Torchbooks: New York. P. 169