ART A pearl of poetry and paint A lavishly illustrated 16th century

advertisement

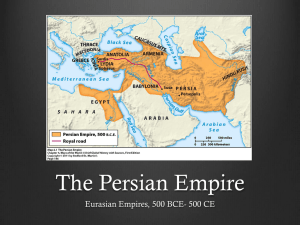

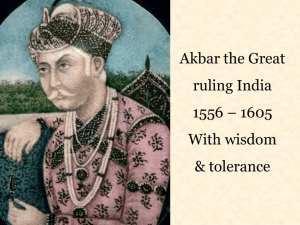

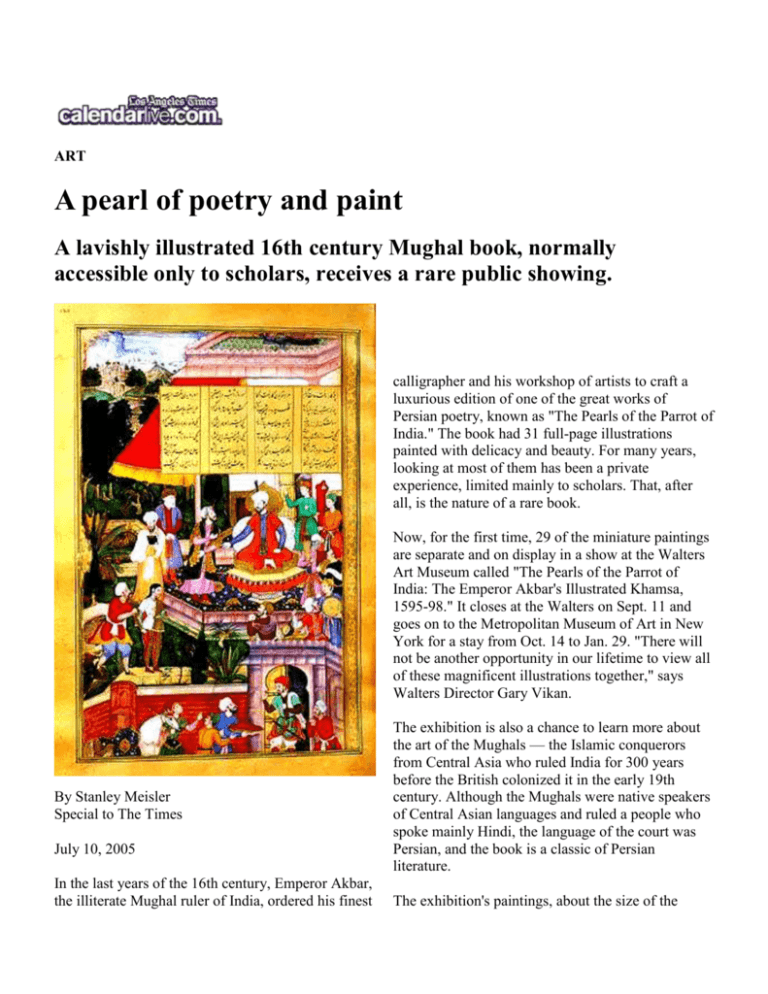

ART A pearl of poetry and paint A lavishly illustrated 16th century Mughal book, normally accessible only to scholars, receives a rare public showing. calligrapher and his workshop of artists to craft a luxurious edition of one of the great works of Persian poetry, known as "The Pearls of the Parrot of India." The book had 31 full-page illustrations painted with delicacy and beauty. For many years, looking at most of them has been a private experience, limited mainly to scholars. That, after all, is the nature of a rare book. Now, for the first time, 29 of the miniature paintings are separate and on display in a show at the Walters Art Museum called "The Pearls of the Parrot of India: The Emperor Akbar's Illustrated Khamsa, 1595-98." It closes at the Walters on Sept. 11 and goes on to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York for a stay from Oct. 14 to Jan. 29. "There will not be another opportunity in our lifetime to view all of these magnificent illustrations together," says Walters Director Gary Vikan. By Stanley Meisler Special to The Times July 10, 2005 In the last years of the 16th century, Emperor Akbar, the illiterate Mughal ruler of India, ordered his finest The exhibition is also a chance to learn more about the art of the Mughals — the Islamic conquerors from Central Asia who ruled India for 300 years before the British colonized it in the early 19th century. Although the Mughals were native speakers of Central Asian languages and ruled a people who spoke mainly Hindi, the language of the court was Persian, and the book is a classic of Persian literature. The exhibition's paintings, about the size of the Seizing opportunity The exhibition is possible only because the binding of the book deteriorated over the centuries, forcing restorers to separate its more than 200 pages last year in preparation for rebinding. With the pages loose, the Walters decided to display the paintings on its walls all at once and add eight missing ones owned by the Metropolitan Museum. The book will be rebound and stored in the Walters collection of manuscripts and rare books after the close of the show in New York. As before, the book will not be complete. When Baltimore industrialist Henry Walters purchased it a hundred years ago, 10 of the 31 illustrated pages had been cut out, evidently by a dealer who wanted to sell them separately. Eight showed up at the Met in 1913 as the gift of a collector and will go back to the Met after the show. The whereabouts of the two other illustrated pages are not known. When the Emperor Akbar ordered the crafting of the luxurious book, he was honoring a 300-year-old classic that itself was an adaptation of a classic written more than a hundred years earlier. The who called himself "the parrot of India." Having killed a youth accidently, Akbar offers the mother either his Akbar’s head on a platter or the platter heaped with gold. pages of a coffee table book, depict climactic moments from the moral lessons, historical narratives and Persian folk tales set down in the poetry. The illustrations brim with delightful detail, personable characters and delicate landscaping. Painted more than 400 years ago in what is known as opaque watercolor, the colors are still bright and fresh. Even the few ordinary pages of the book on display — the ones without paintings — are surprising, their finely wrought Arabic script bordered by ink and gold wash drawings of vegetation, horses, men and Islamic symbols. Khusraw, the son of a Turkish warrior and an Indian woman of noble family, was the court poet for several Islamic sultans who ruled India. Although he wrote Hindi songs that have remained popular in India for centuries, he prided himself on his mastery of Persian. Khusraw liked to say he was letting "pearls of poesy drop from my mouth." His best-known pearls took the form of his adaptation, around 1300, of a renowned book known as the Khamsa (or quintet of long poems) by the Persian poet Nizami Ganjavi. Nizami wrote his book around 1200. Khusraw followed the meter and much of the story line of Nizami's five poems, but the words were his own. "He wanted to show that good Persian poetry is written in India," said John Seyller, a professor of art history at the University of Vermont and the author of an exhaustive study of the Walters manuscript. permitted to sign their pages, a rare honor in Mughal manuscripts. "He wanted to show that we Indians can do as well as Nizami." He failed but came close. "Most people would say he's No. 2," Seyller said in a recent phone conversation. "He's still not Nizami." Akbar the Great, a Mughal born in India, ruled the land for half a century, from 1556 to 1605. In his history of the country, Jawaharlal Nehru, the first prime minister of an independent India, described Akbar as "daring and reckless, an able general, and yet gentle and full of compassion, an idealist and a dreamer." Although he could not read, perhaps because of dyslexia, he amassed a library of 24,000 volumes and would summon courtiers to read aloud to him every day. Akbar commissioned sumptuous illustrated manuscripts of works that he regarded as most important. The most elegant are the Khamsa of Nizami, now in the British Library in London, and the Khamsa of Khusraw, now in the Walters. The best-known calligrapher of the era, Mohammad Hussayn al-Kashmiri, who bore the title of "the Gold Pen," was assigned to set down the script of the Khusraw poems. Writing at the painstaking pace of only 16 1/2 lines a day, it took him two years to complete the text. The book was finished in either 1597 or 1598 in Akbar's capital of Lahore, in what is now Pakistan. While the Gold Pen worked on the calligraphy, 13 master painters from the imperial workshop were assigned to produce the 31 illustrations. Although most of the Mughal painters were born in India, they were trained in Persian techniques. They were also influenced by European styles that they had seen in prints brought to India by Christian missionaries. The European influence is reflected in the threedimensional modeling of the figures and the tendency to include distant landscaping in the corners of a painting. The illustrated pages were so highly regarded that four of the artists were Scenes spilling over with life Many things go on in these miniature paintings. In fact, "you sometimes don't realize immediately what the central event is," said Hiram Woodward, curator of the Walters exhibition, as he explained the detail in one, "Layla and Majnun Fall in Love at School." The page illustrates a moment from a poem about two young lovers who, much like Romeo and Juliet, are destined to die for their love. A large teacher, sitting with four students on the carpeted roof of the school, dominates the painting at first. Three students, including Layla, are girls, while the fourth, Majnun (a name that means "possessed by demons"), is a boy. Although Layla and Majnun are studying their books, they can be made out spying on each other as well, she shyly, he intently. On the level below, five rowdy students are fighting, one rolling upside down. painted as many pages as Dharmadasa and Sanvala. It is obvious that a background in Persian literature and folk tales would deepen the pleasure of studying these miniature paintings. Most visitors to the museum don't have that. But the Walters tries to make up for that lack with ample labels and placards, a model of lucid explanation. Outside the school, a guard, a woman walking with a child, and an emaciated beggar draw your attention. The painting is signed by Dharmadasa, a master artist who painted four of the illustrated pages. The focus is easier in a second painting, "To the Surprise of Alexander, Kanifu Sheds Her Armor." In this scene, taken from a poem that narrates the life of Alexander the Great, Kanifu, a Chinese warrior defeated in battle by Alexander, is led before the conqueror. His officers start to strip the armor from the defeated soldier only to discover that the warrior is a woman. "It has been foretold," she informs Alexander, "that my conqueror will become my husband." Alexander looks somewhat puzzled at the submissive woman while his courtiers dash around spreading news about the surprise. The animated scene takes place in a luxurious palace with a lush garden that reveals mountains and a large city in the distance. The illustrated page is not signed but is attributed to the artist Sanvala, who painted three other pages as well. None of the other 11 artists