Art - Mughal India

advertisement

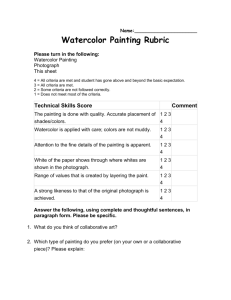

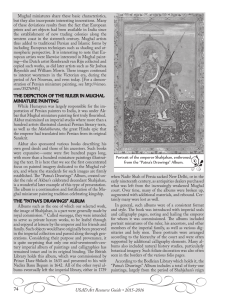

Art Art was a defining feature of Mughal rule. With their distinctive miniature paintings and illustrated manuscripts, the Mughals documented their own history and stories with glittering images of exquisite beauty and detail. Ironically, it was during a low point in Humayun’s reign that a strategic development in Mughal art occurred. During his 15 year exile after being defeated by the Afghan leader Sher Shah Sur, Humayun stayed in various places, including Sind, Iran and Afghanistan. During a stay at the Safavid court, Humayun had time to soak up the architecture of Herat and Samarkand. Most important of all however, was that when Humayun returned from exile in 1555, he managed to persuade two established Safavid court painters to go with him. Back in the re-established Mughal court, painters Abd as-Samad and Mir Sayyid Ali took control of the imperial painting studios, teaching their skills and overseeing artistic production. When Akbar came to power on his father’s death only one year later, his enthusiastic patronage transformed the court ateliers. After the distinctly Persian flavour that Abd as-Samad and Mir Sayyid Ali brought to artworks produced, Akbar also encouraged Hindu painters into his workforce. He also enjoyed reflecting on the Western art that was finding its way into India, often in the form of religious works brought by Jesuits. These collective influences, and the fact that each painting passed through the hands of various artists, resulted in an original new style. Akbar commissioned many great works during his reign. In keeping with his tolerant approach to religion, he commissioned many illustrated manuscripts of religious (including Hindu) and secular topics. An example of such a work is the Hamzanama, which was produced and illustrated in around 1565. Approximately a hundred artists were employed for the mammoth task of producing some 1400 illustrations. Akbar’s son, Jahangir, continued the Mughal tradition in painting. However, Jahangir was concerned more for quality than quantity, and was proud of his connoisseurship of the arts. On ascending the throne in 1605, he immediately dismissed a large number of painters from the court who he Ancient Civilizations – Page 1 of 4 www.mughalindia.co.uk felt were incapable of doing justice to the grandeur of the dynasty at its pinnacle. By contrast, Shah Jahan was famous more for his passion for architecture and fabulous jewels, than painting. During his reign, painting grew rather more stiff and formal, and the number of major manuscript commissions dropped considerably. Aims and Objectives: At first glance, a Mughal painting may look curious to the eye trained in western art. Students can think that the perspective is ‘wrong’ for example, and they may find the heavily detailed patterning and bright colours, unfamiliar. The sourcebook is a useful way of drawing out some of the issues behind looking at art; comparing western and Mughal art and considering the differences between them, for example. Different views on what makes ‘good’ art can also be addressed through the original sources – looking for prejudice, misunderstanding and cultural preferences, as well as considering the purpose of art and how it has changed. Ancient Civilizations – Page 2 of 4 www.mughalindia.co.uk Instructions In the Resources Room, go to the Filing Cabinet. Mughal miniature painting; ‘Humayun in a Tent.’ In the Art folder, compare images E and F. Jot down your observations in the table. Not all the questions will be relevant to both paintings. Image E Image F Colour: Are the colours bright? Realistic? Atmospheric? Cheerful? Does any one particular colour dominate the picture? Nature: What do you make of the trees and the shrubs in the paintings? Do they look realistic? Are they detailed? How has the artist chosen to represent them? Organisation / Composition: How has the painting been organised? Is it a ‘busy’ picture with lots going on – or is it more spaced? Is every area of the picture full, or are there empty areas? What effects do your observations have? Perspective: Can you believe what you see in the painting? Does it look realistic – or do things look ‘flat?’ Can you look into the distance – or does everything look close to you? Are your eyes drawn into the picture, Ancient Civilizations – Page 3 of 4 European watercolour painting by JMW Turner, from 1816; ‘Vale of Ashburnham.’ www.mughalindia.co.uk or do you find yourself looking all over it? Ancient Civilizations – Page 4 of 4 www.mughalindia.co.uk