ECOLE DES MINES DE ST ETIENNE

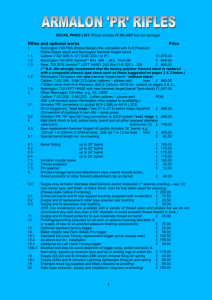

advertisement

ECOLE DES MINES DE ST ETIENNE DEPARTEMENT DES LANGUES N/LBS/JANUARY 1999 BLACK GOLD Is helped fuel the thatcher boom and generated hundreds of thousands of jobs. For the last quarter of century North Sea Oil has been one of the main stays of the British economy. But, no longer. The reason is simple enough : plunging prices. The Asian economic crisis and a couple of mild winters have suppressed demand and sent the price of a barrel of oil plummeting down to between 10 and 12 dollars, around a tenth of what it was in the seventies. Only this week, Shell announced 400 redundancies, the latest in a string of job losses blamed on the continuing fall. So, is this the end of the pipe-line for North Sea P. Crude or can an industry which keeps a third of a million people in work find a way to survive? Michael Robinson reports: the Crommerty Firth near Inverness: from the sheltered waters have emerged some of the mightiest platforms of the North Sea. Around 5000 people now work in these yards, injecting around £ 100 M a year into the local economy. But the cold winds of the Asian recession have now reached the British oil industry, as the prices hit rock bottom. The yards now working flat out. Porter Cabins have been put up to extend the canteen and give everyone somewhere to eat and relax, but these additional facilities soon won’t be needed. Jobs at the yard depend on orders from oil companies, but the collapse in prices has slashed their income. As a result there’s next to nothing on the yard’s books after the present contracts are completed in early summer. “Our prospects are questionable. We have some smaller projects, and we have some bids going, but without a doubt we’re going to see a considerable reduction in numbers of people and we are getting on with looking at other prospects but we will see a dip.” “How big do you think that job losses are likely to be?” “Well it’s a bit uncertain because we don’t know exactly what we’ll get, but they’ll be significant.” Drilling rigs are now laid up in the Firth. It’s not surprising. Last year, a leading oil economist calculated that at $12 a barrel, only half of the 40 prospective new oil fields were viable, so there’s less work for the rigs. We asked what happens when the price drops to $10 a barrel, as it did last month. “When we dropped the price to 10, we found that only 12 out of the 40 would be viable, so the activity level in the North Sea is extremely sensitive to what oil prices are over the last year.” “But that’s a huge difference for just a couple of dollars !” “Yes, exactly. The oil price has always been a major determinant of activity levels in the North Sea but now I think we’ve reached a fairly critical level whereby it’s like falling off the edge. That if it goes just a little bit further down, then a lot of new investments are really not viable. For the oil industry, a price of $10 a barrel was until recently unthinkable. But since December, when the price hit below $10, oil companies have been scrambling to revise their plans for the North Sea. “Normally in January, which we’re well into now, we have our business plan done. But this year we’re re-doing it. And we only did it in October, we’re now re-doing it because of the dynamics of this environment.” “And which way is it headed?” “Well, there’s only one way and it’s downward.” Oil prices haven’t been so low since 1973, before Cheikh Yahmani, the then Saudi Oil Minister galvanized the OPEC cartel of oil producing countries. By cutting back production, OPEC quadrupled oil prices, causing an energy crisis in the west. The high prices also encouraged companies to open up new sources of oil, like the North Sea. But today, the once powerful alliance is in disarray. OPEC members are flooding the market with oil, depressing prices and Cheikh Yahmani believes low prices are here for a while. “We have to live with it. I don’t think it’s a passing phenomenon. I think it will continue for some time.” “How long do you think it will continue for?” “It depends on the situation in Irak, and what will happen. It depends on the Asian economy and whether they will really get out of this recession and I hope there will be no world-wide recession. So the price of oil will not be high as before, but it might improve by $2 or so.” A couple of dollars isn’t enough to sort out North Sea Oil’s problems. When the giant Forties field was developed in the mid-seventies oil fetched between 30 and 40 dollars a barrel. Adjusted for inflation, that’s nearly 10 times the price today. With prices at these levels, the North Sea faces a potentially devastating problem of simple arithmetic. It’s calm enough today, but getting oil from underneath these often wild waters is difficult, and it’s expensive. The government and the industry reckon it now costs around $12 a barrel, and that’s more than the market’s being prepared to pay. There’s nothing much anyone can do about the oil price, so, if the North Sea is to have a future, something has to be done about the cost of recovery. Over recent years, production costs have been falling steadily. Enterprise oils platform on the Nelson field, 140 miles off the Scottish coast is far more sophisticated than its predecessors. For a start, the wells from this platform don’t just go straight down. They can be skewed off at angle, reaching deposits far from the platform’s position. So, fewer platforms are needed, and since the platform’s more sophisticated than before, a smaller crew is required to run it. “This sort of technology has allowed the industry to reduce the cost per barrel of fields such as this from about $20 in the 1980’s to around about $12 on average in 1997. Clearly at $12, that’s not enough to get an adequate return on your investment at the current oil prices, but the trends are in the right direction. A 30 minute helicopter ride, south of the Nelson field brings you to the latest entrant in the now quickening race to cut costs. Enterprise Oil Pierre Field has a converted tanker instead of a platform. It’s due to begin pumping its first oil later this month. The tanker deals with the motion of the sea through a so-called swivel at which pipes from the oil wells are drawn up into a special hole in the bottom of the hull. Inside the ship the oil is pumped up and then stored in the on-board tanks. “This is the heart of the whole development concept. Without this component nothing works.” “This thing right at the bottom these?” “This swivel at the bottom of the sea bed.” “So that stays the same, it never moves.” “That stays relatively stationary.” “But what happens when the ship moves?” “It’s allowed to rotate, the yellow part which is fixed to the ship rotates relative to the central portion and that’s what makes the whole concept work. Without that, we couldn’t move this vessel in the North Sea and the sort of environment that we experience here, and without that, the field would not be economic. The converted tanker has other cost advantages over a traditional platform. It’s easy to move from field to field and it’s far cheaper to scrap at the end of its life. And it doesn’t need expensive under-sea pipelines to offload its oil. Instead, that’s transferred to tankers through a huge flexible hose-pipe. So what difference does it make having this? This reduces the costs per barrel for the field because we avoid the cost of laying a pipe-line from the very first years of production. Ian Craig says in the theory costs could be driven down below $10 a barrel, but with companies having lost 40 % of their oil revenues through the price collapse, it’s hard to find the investment money required. Getting the cash for Research and Development in this environment is much much more difficult than it’s been in the past. That’s for sure. The industry will however still attempt to divert what it needs into those areas to sustain its future. New exploration is essential if the North Sea is to go on producing oil much beyond 2010. CRINE, the industry body set up to promote cost cutting says the government could encourage exploration by reducing its technical demands. At the moment the government requires us to drill very high standards of wells. They want us to provide lots of information. We believe we can actually drill these wells far more cheaply, we believe that we can have them drilled 30 % more cheaply, but we do need the government to agree. Even if the government did agree to cheaper drilling techniques for the North Sea, a new wave of exploration is unlikely. That’s because it turns out that the $12 a barrel cost estimate everyone’s been working with is too low. The cost of unsuccessful exploration drilling was left out of the calculation. So, to get the true cost, CRINE has had to revise its estimate upwards. “The Conclusion is that perhaps the true figure is $14 a barrel. That’s higher than you and the government were previously estimating. Yes, because what we’ve done included in this an amount for the abortive cost of exploration, that’s the money you spend after the new profit to find new reserves. So, the gap between the cost of oil and the price is much bigger than we thought. “Yes absolutely right.” That new $14 cost estimate will make North Sea Exploration look even less attractive. And if the emerging between major oil companies produces savings, it’s less likely they’ll be used to find new North Sea reserves. Despite these rock bottom prices, North Sea Oil is going to continue to flow. That’s because when a company’s already spent the money to find and develop a field, well it usually makes sense to keep the pumps running. But when it comes to the new fields of the future, it’s not surprising that given these low prices, more and more companies are increasingly looking to developments elsewhere. At present prices, the warmer shallower waters of the Gulf of Mexico seem far more attractive. Mexico is not alone in offering less onerous conditions to companies and the prospect of far lower costs per barrel. Whatever happens to prices, the North Sea Oil industry and the jobs it supports are already thought to have passed their peak. But it’s prices that will largely determine the rate at which this still massive British industry will pass into history.