New - Peer Assessment System

advertisement

A Peer Evaluation System to

Improve Student Team Experiences

Robert Anson

Information Technology and Supply Chain Management, Boise State University, Boise, United

States

Robert Anson

Boise State University

1910 University Dr. MS 1615

Boise, ID 83725

(208) 426-3029

ranson@boisestate.edu

Abstract

Instructors frequently include group work in their courses, but there is substantial evidence that

insufficient attention is often paid to creating conditions under which student teams can be successful.

One of these conditions is quality, individual and team level feedback. This exploratory study focuses

on the design and test of a student team improvement system. The system consists of software to

gather and report peer evaluations, and a process for student teams to process their feedback into team

improvement strategies. The system was tested on 13 teams to determine if it met three design criteria.

First, the findings demonstrate that administering the feedback process was very efficient for the

instructor and students. Second, the peer feedback elicited from students was found to be timely,

content-focused, specific, constructive, and honest. Third, evidence suggests that the team experiences

were positive for the students.

Keywords: peer evaluation, team, feedback, collaboration

1. Introduction

Why do students hate group assignments? At the sixth annual Teaching Professor conference,

three undergraduates were invited to talk about their student experiences. They made a plea to the

college instructors, "no more group assignments—at least not until you figure out how to fairly

grade each student’s individual contributions."(Glenn, 2009) Their principle complaint was that

"it’s inevitable that a member of the team will shirk." Their second complaint was called the

"Frankenstein Effect", where the desired group synthesis of ideas devolves into cut and pasted

sections separately written by individuals. Instructor goals, such as peer-learning or cross-cultural

synthesis, are lost to expediency and insufficient group process skills.

Both shirking and the Frankenstein Effect may easily result when the instructor assigns

only a group grade. Individual team members perceive that they bear all the costs of their own

Anson - Peer Evaluation System

Page 2 of 22

extra efforts, but reap only an equal share of the benefits. As a result, many instructors use peer

evaluations to measure individual efforts and differentially assign rewards, or as a feedback

mechanism to help members improve team behaviors.

Based on a review of the literature, an effective peer evaluation process should

accomplish the following goals:

1) Efficiently administer the feedback process

2) Provide quality feedback

3) Foster positive student team experiences (e.g. reduced shirking and Frankenstein effects)

The exploratory action-research study reported in this paper developed a student team

improvement system involving software and process to implement these three goals. The system

was tested in two classes with semester-long team projects across three rounds of peer evaluation.

This article will first examine research on student team problems, the factors that affect their

success, and experiences with peer evaluation. Next the paper will discuss the approach followed

in this study to team management and peer evaluation—including the design of a system to

efficiently collect and compile evaluations plus a process for constructively applying the

evaluation information. Finally the results are presented and discussed.

2. Prior Research On Student Teams

Research has documented, with substantial agreement, the types of problems student teams

experience, and various factors that can obviate the frequency or impacts of these problems.

2.1 Problems with Student Teams

Oakley et al. (2007) conducted one of the largest surveys regarding student team work, at

Oakland University in Michigan. They included team questions in routine course evaluation

surveys for 533 engineering and computer science courses over two years, with a total of 6,435

engineering student responses. Team work was widespread; 68% of students reported working in

teams. Overall, ¼ of the students were dissatisfied to some extent with their teams, with higher

rates of dissatisfaction among less experienced students, especially freshmen and sophomores. At

Anson - Peer Evaluation System

Page 3 of 22

San Jose State, Bolton (1999) found similar results: 72% of business students reported working

in teams, with 1/3 reporting some dissatisfaction.

Regarding the problem of shirkers or slackers1, the Oakley et al. study (2007) found that

one or more slackers were reported on 37% of teams. Also, there are more slackers in

undergraduate classes: 1/3 of undergraduates versus 1/5 of graduates reported a slacker.

One finding by Oakley et al. (2007) should encourage instructors to become more serious

about team work in their courses: student team satisfaction is significantly correlated with the

teacher’s overall rating, with the course as a learning experience, and with the perception that

course objectives had been met.

2.2 Factors Affecting Student Team Functioning and Satisfaction

Oakley et al. (2007) found that the largest factor affecting student satisfaction was the presence of

a slacker. Students on teams with no slackers had a mean satisfaction of 3.4 on a 5 point scale, (5

is very satisfied, 1 is very dissatisfied) whereas that dropped to 2.5 with one slacker, and further

to 1.8 with 2 slackers. Satisfaction even improved some when the instructor gave teams an option

to exclude slackers from authorship or to fire them, even if the option was never used (which is

usually the case).

Team composition is another factor that can influence student team experiences. Oakley

et al. (2004) recommend that the instructor form teams because it reduces interaction problems

among team members. Their selection criteria include diversity, common meeting times outside

class, and not isolating at-risk minority students in their initial years on teams. Similarly, Blank

and Locklear (2008) advocate instructor selection; however they prefer to form groups who are

homogeneous with respect to GPA or team skills. They found member homogeneity results in

1

Shirkers, slackers, hitchhikers, couch potatoes, free riders are only some of the varied names used to describe those

who engage in the behavior better known as social loafing in the research literature. In this article, we will

use the term slacker for consistency.

Anson - Peer Evaluation System

Page 4 of 22

less conflict and higher satisfaction. Vik (2001) recommends selection criteria of experience,

language facility, and gender.

Bacon et al. (1999), in contrast, found that self-selected MBA teams were more satisfied,

cooperative, and likely to complete work on time. However, like Vik, these positive effects were

more pronounced after the students first. They discuss the emergence of student “meta-teams”

across classes. Social structures develop through repeated interaction which can have strong

performance benefits. Overall, they recommend “constrained self-selection” in which students

are allowed to form teams that meet certain criteria.

A third factor is team longevity. Both Bacon et al. (1999) and Blank and Locklear (2008)

recommended that teams work together as long as possible. Oakley et al. (2004) proposed giving

students more control over longevity. The instructor can announce that all teams will dissolve

and reform after 4-6 weeks unless team members ask to stay together. They found that students

are more satisfied with some control over team membership, even though students rarely ask to

dissolve their team.

A fourth factor is size. Oakley et al. (2004) recommend three or four because social

loafing is more likely on larger teams. Bacon et al. (1999) recommend the smallest size

consistent with pedagogical outcomes, although they found no relationship between size and

performance.

Finally, a recommendation echoed by numerous researchers is to provide effective

guidance and training support for teams. Bolton (1999) reports that, at her university, 72% of

faculty made team assignments, while 81% provided little or no support for teams. Bacon et al.

(1999, p8) suggest that training we do provide often lacks effectiveness because it focuses on

“understanding of team dynamics and factors that contribute to team effectiveness, rather than on

developing team skills and building effective team processes.” Oakley et al. (2004) recommends

Page 5 of 22

Anson - Peer Evaluation System

that instructors clearly describe their guidelines for teamwork, and ask teams to prepare a signed

agreement outlining their role and responsibility expectations of one another.

Various researchers emphasize that training should address relevant, immediate team

issues. Vik (2001) suggests targeting training and interventions to the teams’ developmental

stage. Bolton (1999) advocates just-in-time coaching by the instructor. Three strategic training

interventions across the term are recommended to help teams start up, manage conflict, and learn

from their experiences. Kaufman and Felder (2000) emphasize immediacy—dealing with

problems as they begin to surface. They suggest periodic ten minute “crisis clinics” in which

students work on scenarios similar to issues relevant to their particular stage of development.

2.3 Peer Evaluation

Peer evaluation is widely used by instructors to assign individual grades, discourage social

loafing, and help students learn from others observations of their behavior. In general, peer

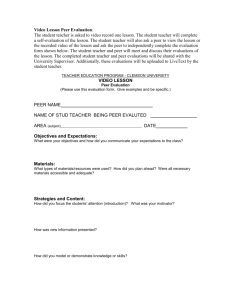

evaluations assessing one another using ratings and or open-ended questions. Figure 1 illustrates

two dimensions classifying approaches: content and purpose.

Team

Citizenship

Behaviors

Process

Quality

Process

Improvement

Product

Quality

Product

Improvement

Summative

Formative

Content

Contribution

to Final

Product

Purpose

Figure 1 Peer Evaluation Approaches

Oakley et al. (2004) distinguish the content of peer evaluations as focusing on individual

contribution to the final product, or team citizenship—one’s efforts and actions that are

Anson - Peer Evaluation System

Page 6 of 22

responsible and team-oriented. They recommend the latter process-oriented approach because it

“stresses teamwork skills over academic ability.”(pp.17) Focusing on citizenship behaviors will

penalize slackers, encouraging students to apply their best efforts cooperatively; focusing on

product contribution would punish and de-motivate academically weaker students.

The purpose of peer evaluation may be summative or formative. Summative evaluation

occurs at the end of the team endeavor to determine a grade. Formative evaluation is conducted

during the class or project to provide feedback for improving the work product or processes in

progress. Both are frequently used. Oakley et al, (2004) emphasize interim formative

evaluations. Bacon et al. (1999) caution about using end-of-term, summative peer evaluations.

They suggest that summative evaluations may actually expand team differences, encouraging

members to tolerate undesirable behaviors instead of confronting them, “thinking that they can

‘burn’ those they are in conflict with at the end of the quarter on the peer evaluations.”(p.474)

Kaufman and Felder (2000) developed a summative, team citizenship-oriented, peer rating

system for student teams—the process quality quadrant of Figure 1—applying it to 57 teams.

They found no significant difference between student self-ratings and averaged teammate ratings.

In fact, deflated self-ratings (14%) were more common than inflated ones (6%). Often instructors

are concerned teams will rate everyone the same to avoid hurt feelings, however only four of 57

teams did so. They also found that peer ratings were positively correlated with test grades. They

suggest spending more time preparing students to complete evaluations, perhaps having students

practice rating team members described in a case.

Dominick et al. (1997) compared behavioral changes over two task sessions for teams in

three peer feedback conditions: gave and received feedback (feedback groups), only gave

feedback (exposure groups), and neither gave nor received feedback (control groups). They

found the feedback and exposure groups experienced significantly more behavioral change than

the control groups. More interesting was that there was no significant difference between the

Anson - Peer Evaluation System

Page 7 of 22

feedback and exposure groups. Thus, to change the evaluator’s behaviors, giving feedback on a

peer feedback survey is more important than actually receiving the feedback. The researchers

speculate that this was due to behavioral norms being communicated via the survey questions, and

monitoring the feedback. However, in their study the teams might be more accurately described

as groups. They only met twice, for one hour each, in a simulated environment. Members had

little stake in their team performance, nor were subjected to developmental dynamics that occur

over time.

Gueldenzoph and May, (2002) reviewed the peer evaluation literature for best practices.

Among those they found included:

Ensuring students understood the assessments before the project begins

Including non-graded, formative evaluations to help the team surface and resolve

problems during the project

Allowing students to assess their own role as well as others in summative evaluations

Cheng and Warren (2000) also raised a practical issue with peer evaluations—the

extensive instructor time and effort required. “The logistics of conducting peer assessment are

more convoluted using this system. With refinement of the system and use of suitable software,

we believe that the method could be made simpler and less time consuming to implement.”

(p.253) It is even more problematic when trying to compile confidential peer comments,

multiplied by the number of evaluation rounds.

McGourty and DeMeuse (2000) built and tested a computerized tool to collect and report

student team peer evaluations for individual, team and course feedback at the University of

Tennessee. Later it was incorporated into a comprehensive student outcomes assessment system.

(McGourty et al., 2001) Unfortunately, it does not appear to be in widespread use currently.

In sum, there is substantial agreement on many best practices for student teams, such as

instructor assignment, smaller size, and providing team training and guidance. There is strong

support for peer evaluations as well, particularly for formative feedback. Most evaluations focus

on team citizenship behaviors in order to not discriminate against academically weaker students.

Anson - Peer Evaluation System

Page 8 of 22

One study also pointed out that peer evaluations are very time intensive for the instructor, which

may limit their use.

To fully take advantage of the potential benefits of peer evaluation, the logistics need to be

addressed. The current study will describe an efficient system to collect and process peer

evaluation data. It uses readily available software and a simple, effective discussion process that

can be efficiently administered. The system concentrates on the process improvement quadrant in

Figure 1, generating formative feedback related to team citizenship behaviors.

3. Study

This is an action research study involving two courses taught by the author. “Action research

specifically refers to a disciplined inquiry done by a teacher with the intent that the research will

inform and change his or her practices in the future.” (Ferrance, 2000, p.1) It is conducted within

the researcher’s home environment, on questions intended to improve how we operate.

The principle goal of this study was to investigate a well-designed team improvement

system that contained a strong peer evaluation component. The system design goals were to

create a system that could:

1) efficiently administer the feedback process;

2) promote quality feedback; and

3) foster positive team experiences.

3.1 Situation

The two courses involved in this study were both in Information Technology Management. They

involved junior and senior level undergraduate students working in 4-5 person teams on extended,

multi-phase projects.

One was a Senior Project capstone course in which student teams worked on real client

projects across the entire semester. The five teams had full responsibility for their work and their

client relationship. Most projects involved designing and developing an information system.

The instructor assigned team leaders and members. The second course was Systems Analysis and

Design (SAD), a prerequisite course for Senior Project. The project accounted for approximately

Anson - Peer Evaluation System

Page 9 of 22

50% of the class points. Eight teams worked together through a 13 week project that was

delivered in four phases, or milestones. Teams were selected by the instructor but appointed

their own leader. In both courses, teams prepared a team charter to identify their roles, protocols

and ground rules.

3.2 Team Improvement System

The feedback process was administered by a system consisting of software and processes. Figure

2 illustrates the broad outlines of the overall process termed the Team Improvement Process

(TIP). After the initial class set-up, the instructor may conduct as many formative or summative

evaluation cycles through the TIP as they wish with a minimum of extra administrative effort.

The system components are described below for each step of the process.

3.2.1 Initial Course Set-up

Three types of set-up activities were required for the course. The first was to set-up the teams. In

both courses, the instructor assigned teams using criteria of common meeting time blocks and

diverse skills and interests. Second, in the SAD course, an hour of initial team training was

Anson - Peer Evaluation System

Page 10 of 22

provided in the SAD course (a prerequisite to Senior Project). Students read “Coping with

Hitchhikers and Couch Potatoes on Teams” by Oakley et al. (2004) and related their experiences

back to the case in a short essay, followed by an in-class discussion about team problems and best

practices. Then teams began work on a Team Charter—an extended form of the Expectations

Agreement used by Oakley et al. (2004) —as part of their first project milestone.

The third set-up was the web survey using QualtricsTM software. (www.Qualtrics.com)

After constructing the reusable survey, each course requires a panel created with information

about each student–name, email, course, instructor, team_ID, and team member names. The

panel is reused each time the class does an evaluation. The information is used to customize, for

each student, the invitation message and the survey, prompting the names of each team member

for answering the peer evaluation questions.

3.2.2 Step (a) Peer and Team Reflection Survey

Each TIP cycle starts by emailing the invitation message and survey link to each student for

completion outside of class. The peer evaluation questions, shown in Appendix A, were adapted

from Oakley et al. (2004). There are two sets of questions: open and close-ended peer evaluation

questions repeated for each team member while prompting his or her name, then a set of open and

close-ended questions regarding the team. The entire survey took an average of 17.1 minutes to

complete.

3.2.3 Step (b) Individual Report: Peer Summary and Team Reflection

The instructor downloaded the response data from the survey system into a Microsoft Access TM

database constructed for this purpose. Programs written in to the database automatically

restructured the data and produced reports for instructor and individual students. This program

drastically cut down the time to about five minutes from raw data to printed reports. Appendix B

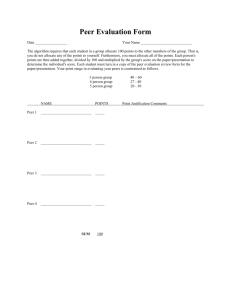

illustrates a sample student report that includes:

averaged ratings on nine questions about his/her “team citizenship” behaviors,

suggestions supplied to student by team members (anonymous),

Anson - Peer Evaluation System

Page 11 of 22

averaged ratings on eight questions about overall team functioning, and

responses to three open ended questions about the team (anonymous).

3.2.4 Step (c) Conduct Team Improvement Discussion

In formative evaluation rounds, the student report was handed out with a few minutes to read.

Then teams met for a focused, fifteen minute team improvement discussion. To guide the

discussion, a simple question procedure drawn from project management: 1) What are we doing

well? 2) What are we doing poorly? 3) What are the top 3 things we should do differently? This

approach is both simple, easily adopted, and exposes students to a common real-world approach.

3.2.5 Step (d) Team Process Improvement Plan

The meeting notes were converted into a team process improvement plan for the team to use in

their next phase of work, and for the instructor to refer.

3.2.6 TIP Evaluation Cycles

Each course conducted three evaluation cycles following its major project milestones. These

included two formative peer evaluations, at approximately the 1/3 and 2/3 points in the class, plus

a final summative round in which the TIP Cycle ended after step (b). In the SAD course,

individual project points—up to 10% of the project points–were awarded based on the student’s

normalized peer evaluation scores. The Cheng and Martin (2000) procedure to calculate scores

was followed. In the Senior Project course, the pattern of individual involvement across the

semester was considered more qualitatively in the final grade.

3.3 Assessment

Various means were used to assess the design goals. To assess efficiency, the instructor recorded

times to conduct each step of the TIP. Feedback quality was assessed primarily using the peer

evaluations feedback comments. Team experiences were assessed using data from the peer

evaluations and team debriefings held by the instructor with each team in the Senior Project

course at the end of the semester. The debriefings were held to request input on the course

design, and included questions on the peer evaluation, “Do you think the peer evaluations and

Anson - Peer Evaluation System

Page 12 of 22

team discussions affected your team functioning at all?” and “How do you usually handle giving

feedback to one another on student teams?”

4. Results

Each design goal—efficient administration, quality feedback, and improved experiences--was met

to some degree. The results are discussed below.

4.1 Efficiently Administer Feedback Process

Table 1 summarizes the preliminary set-up activity for a given course, plus the four steps of the

Team Improvement Process (TIP) repeated for each evaluation. The activities and time required

for the instructor and students is shown for each step. Shaded cells represent activities that

occurred in the classroom.

Overall, it took the instructor about 45 minutes to set up the student data and web survey

software before the first cycle of each course. (Team selection and training time are not included;

these would have to occur regardless of the peer evaluation.) Each cycle required about 25

minutes of instructor time and 35 minutes of student time; only 25 minutes of class time were

needed per cycle.

This could be perceived as an efficient process for two reasons. First, the additional time

to administer each evaluation round (after initial setup) is minimal compared to compiling, by

hand, an anonymous summary of peer comments for each team member. Second, virtually all of

the student time is in value-added activities—reflecting on each team member and the team,

considering peer feedback, discussing potential improvements for the team to undertake.

TIP Step

Initial Course SetUp

Prior to first cycle

for a given class

(a) Collect peer

evaluation and team

Instructor Time

45 minutes

Create panel of student information;

Write messages (Team creation and

training time is not included)

10 minutes

Create distribution and reminder

Cycle Time Per Student

Not Applicable

20 minutes

Open and respond to survey

Anson - Peer Evaluation System

Page 13 of 22

reflection survey

(b) Produce

Individual Reports

using saved panel and messages

over internet

5 minutes

Not Applicable

Download results file, run program

to restructure data and print reports

(c) Conduct team

5 minutes

15 minutes

improvement

Handout individual report plus TIP

Discussion and recording

discussion

planning form and request teams

start discussion

(d) Produce Team

5 minutes

Not Applicable

Process

Copy Team Improvement Plans on

Improvement plans) copy machine

Total 45 minutes (one time set-up)

25 minutes (per cycle)

35 minutes (per cycle)

Table 1 Team Improvement Process Step Times

4.2 Promote Quality Feedback

A primary goal for this project was to give quality feedback to students regarding their team

participation. The criteria that define feedback quality vary, depending on the situation, but there

are a few that are fairly widely accepted in the literature. Quality feedback needs to be timely,

content-focused, specific, constructive, and honest.

4.2.1 Quality feedback should be timely, following as soon after the behavior as possible

The system’s efficiency allowed evaluations to be made as frequently as needed, in this case at

major milestones. Thus, feedback could be closely linked to the related behavior.

4.2.2 Quality feedback should focus attention on the content, not the source, of feedback

When the source of feedback is identified, the receiver is more likely to interpret it in light of their

perceptions of that person. To enhance the receiver’s focus on the feedback content, the system

removed the source’s name from each piece of feedback in the student report. It can be argued

that in a group of four or five, one might surmise the author of certain comments, however

anonymity at least will not reinforce the source’s identity.

4.2.3 Quality feedback should be specific to the individual

Generalized feedback, or feedback filtered by the instructor, may be seen as less relevant, and

hence less effective to motivate change. The survey was designed to display the name of each

team member to the student for them to answer the set of open and closed ended questions for

Anson - Peer Evaluation System

Page 14 of 22

specifically that individual. The resulting specificity is evident in comments represented in Table

2. (Identifying information has been altered.)

Betty is a great teammate and has a sharp eye. She constantly looks at situations from a

different perspective and asks questions to make sure we have everything covered.

More frequent communication with team members will be really helpful.

Be sure to tell people when you need help.

Frankie adds humor to help break the tension and get our creative juices flowing.

Try to be more open to using resources and materials outside the project.

I’m all about procrastination, but come on man, deadlines are deadlines.

Karl, you were amazing this semester. My suggestion is try to let your teammates take

more responsibility. It's tough when their work isn't at the same standard as yours, but

everyone learns from contributing.

Try to listen to team members ideas, it is hard for you to consider others' opinions.

Keep focused during team meetings

Julia offered so much talent to our group. Thanks for your hard work, and helping teach

the group some new things.

Table 2 Sample Student Peer Evaluation Comments

4.2.4 Quality feedback should emphasize open-ended, constructive suggestions

The survey asked respondents to input constructive suggestions to help the person improve their

team participation and contribution. Comments in Table 2 illustrate the diversity of constructive

comments made. Overall, the comments included frequent positive remarks and constructive

suggestions. Very few were solely negative problem statements.

One further perspective on feedback quality surfaced in the interviews. Every one of the

Senior Project teams emphasized that, in other classes, students do not typically give feedback to

other team members about their participation or team skills except in the wake of a major flareup. Students will comment on the content of other’s work, editing grammar or suggesting ideas,

but not normally team behaviors. In fact, over 80% of the peer evaluations in this study included

comments and most of these comments included constructive suggestions. The first step toward

gathering quality feedback is to get any feedback at all.

4.2.5 Quality feedback should be honest

After the semester was complete for the Senior Project class, the author conducted a debriefing

with each of the five teams to discuss their perceptions of the questions about the course overall,

Anson - Peer Evaluation System

Page 15 of 22

including a specific question about the peer evaluation process that was used. Most students said

they were not comfortable with, or disliked, evaluating other students when the feedback would

go to the other students. The problem was with hurting others feelings. “It is hard to be brutal

because they will see it”. As a result, various students remarked that is was difficult to be fully

honest, “It was helpful, but you tend to be less honest than you should be. So, it is less helpful

than it could have been.” No one, however, recommended not conducting peer evaluations. As

one student said, “It was a necessary evil, same as work evaluations.” Some were even more

positive. “It was useful because it forced you to reflect.” One team felt that “More negative

feedback was needed.” In addition, the team improvement discussions were seen as useful.

Despite the fact that students expressed discomfort over giving brutally honest feedback,

their comments on the peer evaluations suggest that some students were able to overcome that

discomfort, at least in part. This can be seen in some of the examples in Table 2.

4.2.6 Quality feedback summary

Overall, the feedback generated using the system met all of the quality criteria. The efficiency

allowed conducting evaluation cycles closely following the activity. Removing the feedback

source from comments and ratings help maintain focus on its content. Through prompting, it

effectively led to feedback that was very specific to the individual being evaluated and

emphasized open-ended, constructive improvement suggestions. By the student admission in the

interviews, the feedback was not as honest as it could have been, however the comments

themselves suggest that neither were many students overly inhibited.

4.3 Foster Positive Student Team Experiences

Two pieces of evidence suggest that team experiences were positive, although they lack a baseline

to draw solid conclusions. A general question about one’s satisfaction with their team (in Oakley

et al., 2007) was not asked. Instead, team experience was addressed by questions regarding how

often eight important team processes occurred, such as owning solutions, assigning tasks, staying

Anson - Peer Evaluation System

Page 16 of 22

focused, planning work, contributing equally, etc. (See specific items in Appendix B, question

C1) A second, indirect, approach to team experience was through a question about each peer’s

involvement.

The questions about team processes applied a scale from one to five (1=Never

5=Always). The results in Table 3 show the combined average score of all eight questions. All

reverse-coded questions were reoriented to a 1-5, from least to most positive.

Analysis and Design

Overall

Senior Project

Overall

Class Teams

Average

Class Teams

Average

A

2.90

I

4.06

B

3.33

J

3.63

C

3.22

K

3.78

D

3.29

L

3.22

E

4.00

M

3.78

F

3.72

Class Total

3.70

G

3.84

H

4.41

Class Total

3.57

Table 3 Average Team Evaluation Scores Overall

Table 3 shows that only one of the 13 teams reported that the overall quality of their team

processes was unfavorable, interpreting marks under the mid-point of 3.0 as unfavorable. Team

A was relatively the most challenged by owning solutions, planning work, and completing work

at the last minute. (This last process was the most problematic for nearly all teams.) Consistent

with Oakley et al. (2007) findings regarding team satisfaction, the senior-level teams rated their

processes higher than the junior-level teams. In contrast to the 8% (1/13) unfavorable team

process quality found in this study, Oakley et al. (2007) and Bolton (1999) found dissatisfaction

rates of ¼ and 1/3 respectively among students working in teams

Oakley et al. (2007) found that slacking and team satisfaction were highly correlated.

Evidence in this study on slacking was derived from a single, confidential rating of each peer on

the final evaluation. “For {Team_Member}, please rate his/her level of participation, effort and

sense of responsibility, not his/her academic ability. This evaluation is confidential and will not

Anson - Peer Evaluation System

Page 17 of 22

be shared with your team members.” (See Appendix B, question B2.) A slacker is defined here as

one who received an average score of 5 or higher on a 9 point scale (1=Excellent, 5 =Marginal,

9=No Show) on the peer evaluation. No slackers were identified among the 8 teams in the SAD

course, one of the only times in the author’s eight years teaching the course that there were no

significant problems with a team. In the Senior Project course, one person could be characterized

as a slacker, although he/she was the only one who lacked sufficient programming skills. There

were other activities this person could have taken on more extensively, but, with the heavy coding

required, he was at a distinct disadvantage on the team.

5. Discussion

This study provided some initial support for the possibility that a more efficient system, making

feedback easier to provide more often, might also encourage higher quality feedback. Feedback is

seen as a necessary—though not sufficient—ingredient in one’s ability to improve individually,

and the team’s capacity to improve. The frequency and quality of feedback may have played a

role in the positive team experiences found.

The software was very efficient than at generating feedback in the three evaluation rounds.

Further formative rounds could have been easily added if teams were still having problems. In

addition, the quality and quantity of feedback was high, potentially enhanced by the interventions.

Finally, the team experiences were quite positive in terms of favorable team behaviors and the

near absence of slackers.

Relatively few changes are needed to the system. Questions should be added to the

survey’s team section, regarding one’s satisfaction with the team overall and the existence of

slackers, to enable comparisons with other studies. It would be helpful to add a capability to the

software for comparing multiple rounds of peer evaluations to track progress across the team’s

lifespan. Also, two suggestions by Kaufman and Felder (2000) should be tested to improve the

Anson - Peer Evaluation System

Page 18 of 22

efficacy of the intervention: adding a preliminary, case-based, practice cycle, and applying

guidance in brief “crisis clinics” at key team development stages.

The current exploratory study has successfully tested the mechanism of change, and found

consistent, positive results. However, its small sample size and narrow range of conditions are

not sufficient to establish causality. The next step is to apply this system to more teams, working

in a variety of courses, instructors, and team interventions, including control conditions.

Finally, research in this field needs to expand beyond the goal of single-loop learning to

that of double-loop learning. “Single-loop learning occurs when errors are detected and corrected

without altering the governing values of the master program. Double-loop learning occurs when,

in order to correct an error, it is necessary to alter the governing values of the master

program.”(Argyris, 2005, pp. 262-263) Applied to student teams, improved immediate team

experiences are great, but developing the student’s ability to work more effectively on future

teams is a far more important goal. Researchers could consider longitudinal studies following

students working on teams across multiple terms, teams and classes. Alternatively, it may be

possible to use a pre and post test of team behavioral knowledge. While a less direct measure, it

could also serve as a predictive tool for individual abilities and a means of measuring the

effectiveness of different interventions. Such a test would need to focus on situation-appropriate

behaviors, versus knowledge of team terminology or theory. The Team Knowledge Survey,

developed by Powers et al. (2001) provides an excellent foundation for this type of test, although,

according to Powers (personal communication, January, 2009) the instrument has not yet been

formally validated.

6. Conclusion

Oakley et al. (2007) summed up their report with the following, “Students are not born knowing

how to work effectively in teams, and if a flawed or poorly implemented team-based instructional

model is used, dysfunctional teams and conflicts among team members can lead to an

Anson - Peer Evaluation System

Page 19 of 22

unsatisfactory experience for instructors and students alike.” (p270) Perhaps the first step toward

improving team experiences is for instructors to apply best practices to how we set up, train, and

guide our student teams.

Bacon et al. (1999) wrote, “Students learn more about teams from good team experiences

than from bad ones.” A key best practice for fostering positive student team experiences is to

provide individual students and teams with timely and repeated, high quality feedback. Without

feedback, students will not be able to learn to improve their behaviors—this time, or the next time

around.

REFERENCES

Argyris, C. 2005. Double-Loop Learning in Organizations: A Theory of Action Perspective. In

Great Minds in Management: The Process of Theory Development, ed. K.G. Smith, and

M.A. Hitt, 261-279. Oxford University Press.

Bacon, D., K. Stewart, and W. Silver. 1999. Lessons from the Best and Worst Student Team

Experiences: How a Teacher can make the Difference. Journal of Management Education

23, no. 5: 467-488.

Blank, M. and K. Locklear. 2008. Team Work in On-line MBA Programs: An Evaluation of Best

Practices. http://www.ce.ucf.edu/asp/aln/cfp/presentations/1209048502517.doc.

Bolton, M. 1999. The Role Of Coaching In Student Teams: A Just-In-Time Approach To

Learning. Journal of Management Education, 23, no. 3: 233-250.

Cheng, W. and M. Warren. 2002. Making a Difference: using peers to assess individual students’

contributions to a group project. Teaching in Higher Education 5, no. 2: 243-255.

Dominick, P., R. Reilly, and J. McGourty. 1997. The effects of peer feedback on Team Behavior.

Group and Organization Management 22, no. 4: 508-520.

Felder, R.M. and Brent, R. Forms for Cooperative Learning. http://www.ncsu.edu/felderpublic/CLforms.doc.

Ferrance, E. 2000. Action Research. Northeast and Islands Regional Education Laboratory,

Providence, RI: Brown University.

Glenn, D. 2009. Students Give Group Assignments a Failing Grade. The Chronicle of Higher

Education, June 8, 2009. http://chronicle.com/daily/2009/06/19509n.htm.

Gueldenzoph, L. and L. May. 2002. Collaborative peer evaluation: Best practices for group

member assessments. Business Communication Quarterly 65: 9-20.

Kaufman, D. and R. Felder. 2000. Accounting for individual effort in cooperative learning teams.

Journal of Engineering Education 89, no. 2: 133-140.

McGourty, J., L. Shuman, M. Besterfield-Sacre, R. Hoare, H. Wolfe, B. Olds, and R. Miller.

2001. Using Technology to Enhance Outcome Assessment in Engineering Education.

Paper presented at the 31st ASEE/IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference, October 1013, in Reno, NV.

Anson - Peer Evaluation System

Page 20 of 22

Jack McGourty, J. and K. DeMeuse. 2000. The Team Developer: An Assessment and Skill

Building Program Student Guidebook, Wiley.

Oakley, B., R. Felder, R. Brent, and I. Elhajj. 2004. Turning Student Groups into Effective

Teams. Journal of Student Centered Learning 2, no. 1: 9-34.

Oakley, B., D. Hanna, Z. Kuzmyn, and R. Felder. 2007. Best Practices Involving Teamwork in

the Classroom: Results from a Survey of 6,435 Engineering Student Respondents”, IEEE

Transactions on Education 50, no. 3: 266-272.

Pieterse, V. and L. Thompson, L. A Model for Successful Student Teams.

http://www.cs.up.ac.za/cs/vpieterse/pub/PieterseThompson.pdf.

Powers, T. A., J. Sims-Knight, S.C. Haden, and R.A. Topciu. 2001. Assessing team functioning

with college students. Paper presented at the American Psychological Association

Convention, in San Francisco, CA.

Page 21 of 22

Anson - Peer Evaluation System

APPENDICES

Appendix A Peer Evaluation Survey

A. Individual Team Member Assessments (Completed for each team member)

1. For {Team Member}, please evaluate his/her actual performance in the following areas.

Scale: 1=Never, 2=Rarely, 3=Sometimes, 4=Frequently, 5=Always

Attends team meetings?

Communicates and responds promptly with team mates?

Meets team deadlines to complete assigned work?

Produces work that meets or exceeds group or project requirements?

Willingly volunteers for, and carries out, work assignments?

Add constructive ideas in team meetings?

Listens and respectfully considers teammates' ideas and opinions?

Provides emotional & motivational support to team members?

Contributes to team planning, coordination and leadership?

2. For {Team Member}, please rate his/her level of participation, effort and sense of

responsibility, not his or her academic ability. This evaluation is confidential and will not

be shared with your team members. Scale: 1=Excellent; 2= Very Good; 3= Satisfactory;

4= Ordinary; 5=Marginal; 6= Deficient; 7=Unsatisfactory; 8= Superficial; 9= No Show

3. For {Team Member}, please make at least 1-2 constructive suggestions for them to

improve their team participation and contribution. These suggestions will be shared with

the team member. Open ended

B. Team Assessment

1. Please consider your team overall for this class. For each statement, choose the option

that most accurately describes your team. Scale: 1=Never, 3=Sometimes, 5=Always

My team may agree on a solution but not every member "buys into" that solution.

We are careful to assign tasks to each of the team members when appropropriate.

We have a difficult time staying focused.

My team members criticize ideas, not each other.

My team tends to start working without a clear plan.

Some team members tend to do very little of the team's work.

My team can assess itself and develop strategies to work more effectively.

My team completes its work at the last moment before a deadline.

2. Considering how your team works together, what does your team do particularly well?

Open ended

3. All teams experience some difficulties. What recent challenges has your team faced?

Open ended

4. Considering how your team works together, what does your team need to improve? Open

ended

Page 22 of 22

Anson - Peer Evaluation System

Appendix B Individual Report: Peer Summary and Team Reflection

ITM320 Instructor: Jim Dandy

Doe, John - Team B

Individual Evaluation Averages

Peer Evaluation 3

1 - Never; 3 - Sometimes; 5 – Always

Respondents: 3

Attends Communicates Meets

Contributes Volunteers Constructive Listens to Cooperates Contributes

Meetings Promptly

Deadlines Quality Work for Work

Ideas

Others with Team Coordination

4

4.333

4.666

4.333

4.333

4.333

4.666

4.333

4

Comments from Team Members

I feel John can improve two things: being punctual, and communicating with the rest of the team. It seemed John

struggled in the beginning but has now started to come through and finally on board with the rest of the team.

Continue to give good ideas and contribute your part to the remainder of the project

More thorough proof reading needed if filling that role

None.

Team Evaluation Averages

1 - Never; 3 - Sometimes; 5 – Always

All members Tasks assigned Team usually

buy into team to all members stays focused

agreements

2.2

3.8

3

We criticize

ideas, not

each other

3.6

Work with a

clear plan

2.4

Respondents: 3

All members Effectively

Complete

do team work assess and

work before

work together deadlines

3

3.6

1.6

Comments About Team

Team Leadership and Coordination

Team Collaboration

Team Improvement

The team leader, Sam was not fulfilling his

role and has not been communication

well with other. I have stepped up and

tried to take charge, allocating roles and

responsibilities that were then completed.

The majority of the team communicates

well to ensure that we are all on the

same page.

The whole team needs to communicate

better, unfortunately one person can

hold back the whole team and it is

something that we need to improve

drastically.

There were communication problems

through the first part, but they've been

taken care of and everything is running

smoothly now.

Everyone contributes good ideas

to the project

We're doing well now, we just need to

stay in touch so we can make sure our

ideas are focused and collected.

We had separate tasks that everyone

completed and then we worked together

to complete a final draft of our

assignment.

For the most part, we did the work we

were all supposed to complete. We all

knew what needed to be done to

receive the grade we wanted.

The team leader Ginger Spice needs to be

more organized and set up team meeting

times that work well with everyone in the

groups schedule.