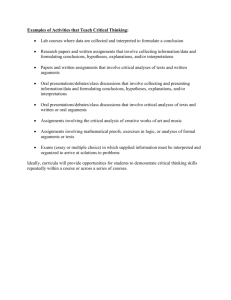

Foundations Skill - Read

advertisement

Read The bullet: to read (that is, to examine carefully and evaluatively) written and other kinds of texts for content and meaning, and, to some degree, to attend to questions of structure and form as they impact and/or shape meaning. The clarification: Someone who is attempting to develop the student’s reading skills will give them practices which foster excellence in ACTIVE and ANALYTICAL reading (to wit): Reading with context in mind Reading for structure Reading to interpret Reading to critically engage Explanation: Reading with context in mind: Reading with attention to who the author is, the time period written (its intellectual, religious, cultural, economic, political, and social situations), any other works to which the given text refers (explicitly or implicitly), the audience the author may have in mind, etc., insofar as these things impact and/or shape meaning. For example, having students identify some of the conditions of the workers explored in the Sadler Report could help illuminate for them the kinds of exploitation referenced in Marx and Engels’ Communist Manifesto. Having some sense of the impact of 19th century industrialism on the workers themselves would make for a more informed reading of the Manifesto. Teaching Strategies There are clearly different levels of attention to context required in different reading settings. What would be required to do due diligence to the context of a text in a graduate seminar will be quite different than what can be required in a predisciplinary course like FDN 111. The goal of this course is not to urge the students to develop a complete picture of the context of our various texts (this clearly isn’t possible), but instead to give them a sense of the importance of attention to context so that they’ll adopt as a habit some consistent attempts to learn something about the situation of the author, the historical setting, and the like as they read any text in the future. With the advent of online resources, the task of reading with context in mind will be easier in some ways (one need not travel physically to a library to access an academic encyclopedia to learn something about an author, e.g.) and harder in others (there is a bewildering array of resources, and therefore some difficulty in determining where exactly to look for good, helpful information). Part of the instructor’s job, therefore, is to encourage the use of these readily available resources, while also offering guidance about how to discriminate between the more and less helpful sites. There will be a collection of useful links available on the Master Moodle site. As a practical suggestion, students might be encouraged to read about the author and selection for a total minimum of 15 minutes at some point in their encounter with each and every selection. Some of those 15 minutes might be spent at the beginning to set the basic frame of the selection, but some of those 15 minutes might also be spent tracking down information based on clues encountered in the selection itself. This idea could be reinforced by including a requirement that in annotation assignments (periodic or ongoing), some basic attention to context should be offered in the margin or in notes taken. All such attempts to ask students to consider context in this setting, it should be noted, carry some risk. Minimal attention to context could prompt students to embrace oversimplified or distorted views of authors or time periods. Students reading about Virginia Woolf, e.g., might focus only upon her suicide as THE key contextual point—this would clearly be counterproductive. So if this approach is adopted, instructors should be attentive to the kinds of information students discover and offer feedback when such oversimplifications and distortions occur as a way of sharpening the contextual reading skill. Ideally, all reading question sets should include at least one “reading for context” question. All five of the required reading question sets should contain such a question. Some examples: Hosea: What were some of the reasons why the kingdom of Israel was alleged to need a prophetic message from Hosea? Explain your answer carefully, and provide at least one piece of evidence for your answer from (1) the text of Hosea itself, (2) the introductory materials to Hosea, and (3) relevant footnotes following the text. Leviathan: Point out at least two places in the reading where Hobbes’ ideas seem influenced by the new mechanical philosophy we discussed during the previous two classes. Briefly explain your answer. To reinforce the importance of reading with context in mind, instructors could use some of the class-time discussion of the texts to highlight ways in which the understanding of the context might influence or deepen meaning or raise issues. Reading for structure: Reading to recognize the major parts of a text, determine their purpose, and understand their relationship to the whole, and reading to recognize the structural elements within the major parts, also with an eye towards their purpose and connections with other parts of the text. Teaching Strategies There are at least two main deficiencies in student performance which better structural reading can strive to address in the context of FDN 111. First, students frequently report that they find themselves in the middle of a challenging text that they are “reading” and don’t really know what’s going on in any significant sense (yet they also frequently report plowing forward anyway with a determination to pass their eyes over ALL the words— understanding be damned!). Several of the readings they’ll encounter strike them as a mass of details that remain a jumble of undifferentiated ideas straight through to the end of the reading. They’ll remember this point or that point (and sometimes can offer an account of those individual points quite eloquently), but fail to see how those individual points add up to anything. They see trees, but no forests. This is a clear sign that they aren’t paying attention to the structure of that reading. Structural reading demands that students wrangle those details into an meaningful order (what part serves as exposition of an idea, one of the central elements of a plot, a key argument or element of an argument, etc.), using the textual clues offered by the authors themselves. Second, students often ignore how the ways in which a particular piece is put together constitute part of its meaning and power. For example, the macro-structure of Thoreau’s Walden takes the reader from a summer beginning (Independence Day) and through the seasons, ending in the cracking of the winter ice of the pond in spring’s rebirth. Though Thoreau was really in his cabin for over two years, the collapsing of the story into a single year of four seasons allows him to convey something of his own internal transformations, mirroring those of the seasons. Students who read the Walden account as a simple list of events, missing this larger organizing structure quite simply miss the point. Reading for structure requires that students remain alert to the ways that structure impact and/or shape meaning. To demonstrate the importance of reading for structure, instructors can put the following list of letters on the board: LSATACTGRESAT. Then they give the students 25 seconds to memorize the list of letters. Many will try and fail. Those who succeed will recognize that the letters fall into groupings that name major entrance examinations: LSAT, ACT, GRE, SAT. The “mass of details” (individual letters) becomes intelligible when situated in a clear structural ordering. It’s also remarkable how much better retention is, if the individual details are situated in a clear structure. If this little exercise is done early in the semester, instructors periodically ask students to recall that string of letters, and not surprisingly they can do it with ease. Similar increases in intelligibility and retention occur when students work to “chunk” texts by seeing the organizational map used by the author and recognizing the roles the various elements play in the larger piece. Students who pursue this strategy aggressively are often very pleased to find a big payoff in independent understanding by the end of the term. Ideally, reading question sets would always contain at least one structural reading question to suggest that this should always be one of the strategies to employ in good reading. All five of the required reading question sets should contain such a question. Some examples: Antigone: See Aristotle’s diagram of tragedy: Exposition, Rising Action, etc. Identify these elements in Antigone. Communist Manifesto: Write up an outline of chapter 1 of the Manifesto. To capture the main macrostructural shifts, include only roman numeral level and capital level headings (e.g., IA. IB., IIA IIB IIC, IIIA… and so on). Exodus: is there any intelligible structural ordering to the 10 commandments? If so, what significance might this ordering have? Leviathan: identify the central premises in Hobbes’ argument that the state of nature is a state of war. Instructors might offer outlining assignments. These would be designed specifically to allow students to identify the macro and micro-structural shifts, identify and articulate the relationships between the parts, and develop the art of pithy summarization which conveys efficiently both the meanings and the roles of the various parts of the selection. Instructors might also use the structure of a selection to organize the classroom encounter with the text. One way to do this is to allow the students themselves to practice reconstructing the macro-structure or some microstructural elements, pointing out the textual clues to validate their choices. Another way is for the instructor to model structural analysis of a whole work or parts thereof in course presentations (power-point presentations, handouts, etc.) elements to demonstrate what the references to structure in good annotations or note-taking should look like. This is important because student representations of structural elements are often poorly constructed (as the instructor may see for him or herself, if the outlining assignments are offered). It helps students to have models which do a good job of efficiently capturing the structural essence of a selection. Reading to interpret: Reading to determine what ideas the author could be expressing both by considering the possible meanings of the various elements of a text (concepts, ideas, symbols, characters, key claims, metaphors, events, turns of phrase, etc.) and by considering how those elements work together to create the meaning of the text as a whole. Possible Teaching Strategies Metaphorically speaking, if reading for structure involves taking x-rays of a text, then reading to interpret requires close examination under a microscope. And careful, close reading to determine the meaning of various elements of a text and the text as a whole is not a practice that comes naturally to our students. As one student reported last year, standardized tests have caused her high school to teach students to skim passages, then return to find answers for questions. In teaching careful, close reading, we may be working against several years of conditioning. Students need help learning which kinds of elements are worthy of such careful scrutiny. They need practice in cultivating the imaginative resources that enable them to see various possible (and often competing) ways to understand an element or a text. They need help learning what counts as worthwhile evidence in favor of a particular interpretation. Reading question sets are a particularly good vehicle to help students improve in these ways, and these assignments should always include at least one ‘reading to interpret” question. Some examples: Exodus: We see the laws laid down in Exodus. What kind of God is this, then? How would we describe him? Iliad: What makes a hero in ancient Greek culture? Antigone: Offer a careful account of at least one of the key conflicts in Antigone. Perceval: The Story of the Grail: What does Perceval: The Story of the Grail suggest about the nature of identity? Freedom of a Christian: Luther draws a distinction between the spiritual and bodily nature of humanity. Appealing to evidence from the text, offer an interpretation of each of these concepts (a paragraph devoted to each). Walden: Offer a careful interpretation of the “sleeper” metaphor in Thoreau’s Walden. In annotation assignments (ongoing or otherwise), students could be encouraged to indicate (with some symbol of their own choosing) what elements of a particular work seem to invite closer interpretive scrutiny (both the clearly ambiguous moments in a text where things are unclear, could go either way, etc., AND the elements that are so central to the meaning of the text they warrant interpretive attention even when they appear to be clearly expressed). In the same annotations, students could be required to offer concise but well-formulated interpretive thoughts about at least one of the elements they’ve identified. Instructors also might assign short interpretive essays which allow students to develop possible interpretations of a piece as a whole or some element of the larger work. Consideration of possible competing interpretations would be encouraged, and any possible interpretations offered would be supported by evidence from the texts themselves. Some examples: Leviathan: Some have claimed that Hobbes believes humans are, by nature, wolf-like. Others have disputed this interpretation. In no more than 3 pages, develop each of these possible interpretations, supported by well-explained textual evidence that might be marshaled in their favor. In a concluding paragraph, offer any reasons you have for supporting one interpretation over the other. Reading to critically engage: Reading in dialogue with the author as an intellectual peer, no longer reading merely to understand but to also to identify the key areas worthy of examination and questioning. (What elements of the text are worthy of examination, vulnerable to criticism, the crux of the matter, the issues that beg for more thoughtful attention?) Reading to make judgments. (Does the text tell a compelling story? Is it beautiful? Is it coherent? Is it clever? Is it well-reasoned? Is it insightful? Does it convey its subject clearly, accurately, and in appropriate depth? Is it true? Does it change minds? Is it elegant? Are its implications defensible? Are its implicit assumptions defensible? Why or why not?) Possible Teaching Strategies Though a student’s first few runs through a text should involve a good bit of wrestling around for understanding, when enough care has been exercised to get a well-considered account of the piece in hand, good reading further demands examination, questioning, judgment. As the questions above indicate, critical engagement moves the student out of the posture of listening in a lecture hall and into a seat at a roundtable discussion with the author. The critical questioning of a text often deepens the understanding of the text even further than the student will have advanced with the three strategies above, and it is often in the critical questioning of a text that students form their deepest attachments to the ideas that hold up well. Instructors may not be able to teach students to have clever things to say about the texts that they read, but they can absolutely create all the space necessary for the students to practice. And by making critical engagement a constant requirement, we may hope to habituate this tendency to “talk back” to texts and ideas of all sorts (ideally beyond the confines of higher education). Ideally, reading question sets would always include at least one ‘reading to critically engage” question. All five of the required reading question sets should contain such a question. Some examples: Hobbes argues that the state of nature is always a state of war. Is he right? Why or why not? Does Thoreau’s Walden experience have anything significant to tell us about our own cultural situation? The believing and doubting game (see below) is a great way to give students the freedom to evaluate a position without having to get all worked up over whether or not they are right. Instructors also might assign short critical essays which allow students to critically engage the texts (as described above). Some examples: In Henry IV, Shakespeare’s Prince Hal represents an early modern makeover of the epic hero. Discuss. Common Student Barriers to the Cultivation of Excellent Reading Skills: Passive rather than active reading. Passing eyes over the page and “reading” the words is not reading (and though some might disagree, making some of the text yellow with a highlighter isn’t much better). Students should read with a pen in hand or a word document open, ready to practice the various analytical reading strategies described above. Reading in less than ideal circumstances (e.g. in conjunction with any social media applications/technologies, in busy dorm rooms, in disjointed fragments of concentration interspersed with conversation, etc.). The extra amount of time INITIALLY added to reading by the adoption of the strategies above. Students commonly complain that these strategies take HOURS. Initially, there is admittedly a kind of plodding awkwardness as the students first adopt the strategies, spending some time on context, reading for structure, paying special interpretive attention to various elements and the text as a whole, and engaging the text critically. But what they can’t know until they’ve internalized these practices is that these things actually increase efficiency along with understanding. When the practices become part of the fabric of their reading, they become second nature, and not so plodding or awkward anymore. Apathy. Why care enough about the Greats to give them such special attention? I think that we need to do a better job talking about why all this matters. Students frequently resist the idea that they should consider themselves intellectual peers of the authors. They lack confidence in raising objections and questioning the authors. Typically this can be resolved with a few STUDENT examples of excellent critical work. Self-Assessment Measures Related to Reading: Annotate texts (or note-taking from texts) as means to self-check comprehension on a rolling basis throughout reading assignments Consciously attempt to improve vocabulary by (a) realizing you don’t know a word, and (b) consciously figuring out the word’s meaning either through context or by using dictionary Carefully read instructor feedback on assignments designed to cultivate reading skills Apply instructor feedback to future readings and assignments designed to cultivate reading skills Keep a log/journal noting your response to/level of interest/level of ease or difficulty with readings and assignments (track whether these things depend on topic, time period, the way a piece is written, your own reading practices, etc.) Sample Assignments : Annotation: these assignments would be taken up to examine how effective student annotation practices are. Ongoing annotation assignments: require students to ALWAYS annotate knowing that you ALWAYS have the option to take them up periodically to track how frequently and well students are doing them without it being assigned. These could be “low stakes” assignments (not factored heavily into the grade). Reading questions: These should be written to explicitly address reading with context in mind, reading for structure, reading to interpret, and reading to critically engage as a way to help students develop the mindset that they always need to remain attentive to these active and analytical reading strategies. “Write your own” reading questions: After students have done a few of the reading question assignments described above, they would be encouraged to practice writing their own reading questions for some assigned text that address reading with context in mind, reading for structure, reading to interpret, reading to critically engage. These kinds of assignments also work well as a goad to get students to practice the reading strategies in other courses (some instructors did this for extra credit, others as a full-blown assignment). Outlining assignments: These are designed specifically to allow students to identify the macro and micro-structural shifts, identify and articulate the relationships between the parts, and develop the art of pithy summarization which conveys efficiently both the meanings and the roles of the various parts of the selection. Reading quizzes: These could be similar to the reading questions but done in class, with or without access to reading notes, to both serve as an incentive for students to practice active reading even without reading questions, etc., and to measure the effectiveness of the practices in enhancing independent understanding, retention, and ability to “say something” about the texts. Short interpretive essays: 1-2 page essays (or even shorter bits of in-class or out of class writing) which ask students to offer at least two possible ways of interpreting a text or an element of a text using evidence from the text itself as support (like the exploratory essay, these might not require the drawing of a conclusion, but would certainly welcome it). Short critical essays: 1-2 page essays (or even shorter bits of in-class or out-of-class writing) which ask students to critically engage the texts (as described above). Believing and Doubting Game: Slightly modified version of the assignment described in the Skills Handbook. Offer a selection of important passages from a given reading which contain key claims (conclusions or premises of arguments) that are controversial. Students write three formal or informal paragraphs: (1)One offers an interpretation of one of these key claims; (2) A second offers the believing response (possible reasons in support of the claim); and (3) A third offers the doubting response (possible reasons to reject the claim). Sourcing: Skills Handbook: Active Reading and Annotation (39-58) Critical Reading (111-125) Argument as Inquiry (148-182) The Logical Structure of Arguments (196-203) Introduction to Close Reading of Literature (354-420) Mortimer Adler’s How to Read a Book.