The Teaching of Spelling and the use of Phonics

Spell chequer

Jerrold H. Zar

Eye have a spelling chequer,

It came with my Pea Sea.

It plane lee marks four my revue

Miss Steaks I can knot sea.

Eye strike the quays and type a whirred

And weight four it two say

Weather eye am write oar wrong

It tells me straight a weigh.

Eye ran this poem threw it,

Your shore real glad two no.

Its vary polished in its weigh.

My chequer tolled me sew.

A chequer is a bless thing,

It freeze yew lodes of thyme.

It helps me right all stiles of righting,

And aides me when eye rime.

Each frays come posed up on my screen

Eye trussed too bee a joule.

The chequer pours o'er every word

Two cheque sum spelling rule.

The original version of this poem was written by Jerrold H. Zar in 1992. An unsophisticated spell checker will find little or no fault with this poem because it checks words in isolation.

1

Contents

Introduction

Elementary Phonic Acquisition

The teaching of Phonics in the Foundation Stage and into Year 1

Teaching of Spelling

Moving beyond successful Phonic Acquisition

Teaching of Spelling

The Pedagogy for teaching Spelling beyond Phonics Lessons

The Assessment of Spelling

The Role of SEN Teaching with regards to Spelling

Meeting the needs of the More Able

Lesson Structure

Conclusion

Appendix 1: The Phonics Pyramid

Bibliography

3

4

6

8

13

14

14

15

16

17

18

2

Introduction

Phonics is a means to an end not an end in itself

As with the pedagogical approach to writing, the debate on phonics should not reduce everything down to a set of secretarial skills. The purpose of both reading and writing is to communicate meaning and understanding, and to this end accuracy in spelling plays a key role but it must not become the be all and end all of the writing process. The fact that most of us these days will be aware that “c u tmz” is a request from a friend to meet up within the next 24 hours is proof enough that spelling is only one element of the communication process. However there can be little doubt that in the reading and writing of conventional English a consistency of spelling and grammar allows both reader and writer to access the inherent meaning within a given piece of literature more easily. As Greg Brooks states ; “Reading is making sense of print, writing is making sense in print and meaning must therefore be at the heart of the enterprise. Phonics is purely a means to this end not an end in itself” (G Brooks –

Sound Sense 2003)

How should Phonics be taught?

Whilst some may wish to debate the merits of spelling within the wider orb of the literary process, for schools the reality is that “The National Curriculum treats phonic work as essential content for learning …” (Jim Rose Independent review of the teaching of early reading p11, 2006) and as every school has a statutory obligation to teach the National Curriculum such a debate becomes quickly obsolete. However as

Jim Rose goes on to say “The National Curriculum treats phonic work as essential content for learning not a method of teaching. How schools should teach that content is a matter of choice.

” Therefore a school ’s time would be well served ensuring that their teaching of phonics is both robust and underpinned by a secure philosophical understanding on the teaching of the subject.

Phonics as the gateway to Literacy

This document seeks to set out for the reader the pedagogical basis on which phonics is taught throughout the school. The school recognises that phonics provide the gateway into understanding of the English language for many children. However there are many children who, for whatever reason, seem to struggle little with the rudiments of the English language. They appear to pick up the mechanics of reading with ease and seem to have photographic memory for spelling. The school recognises that to plough through a rigorous phonics programme with these children is probably both laborious and superfluous.

The teaching of Reading and Spelling

The school would also wish to draw a distinction between the teaching of phonics in terms of reading and spelling. The early teaching of phonics has a profound impact on children’s ability to read, but often does little to assist their spelling over and above providing children with a variety of phonetic possibilities for the spelling of individual words. For instance the word “pain” could just as easily be phonetically spelt “pane” or “payne”. It is at this point that the teaching of spelling through discrete phonics lessons becomes somewhat flawed. The truth is that the phonics teaching has done all it needs to in providing the child with a range of alternatives. The spelling now needs to be taken over by teaching that is context based and where children themselves increasingly gauge the correct spelling through context. Discrete lessons which seek to tease out these differences will not deliver the desired results.

It should be noted at this point that whilst the common perception of Jim Rose’s review in 2006 appears to be that it was a review of phonics teaching it was in fact entitled “Independent review of the Teaching of Early Reading” To this end whilst it may be that much of what he proposes is good for reading, the school would

3

advocate a different strategy is required at certain points with regards to spelling, especially as children move into the deeper complexities of language in Key Stage 2.

Elementary Phonic Acquisition

The teaching of Phonics in the Foundation Stage and into Year 1

The importance of Phonic Understanding

There seems to be general agreement that the teaching of phonics has a key role to play in the teaching of reading and spelling. Ehri Linnea’s research showed that

“…systematic phonics instruction produced superior performance in reading compared to all types of unsystematic or no phonics instruction” (Ehri,Linnea C.

‘Systematic phonics instruction: Findings of the National Reading Panel’. Paper presented at the seminar on phonics convened by the DfES in March 2003). The recent review of the subject by Jim Rose for the government (Independent review of the teaching of early reading, 2006) has brought cohesion to the debate and has provided schools with a document that has been all but universally accepted by the teaching profession. At present therefore there would appear to be general agreement as to the teaching of phonics in the early years and the school would concur with much of the perceived wisdom on this subject.

Phonics a means to an end

The comments made in the introduction to the Letter and Sounds document that

“Phonics is a means to an end” (Letters and Sounds p3, 2003) should not be lost in the day to day teaching of phonemes and graphemes. Teachers should not lose sight of the fact that reading, writing and spelling must be grounded in the belief that literacy is about effective communication and an over emphasis on technical correctness will often be at the expense of creativity and enjoyment. It goes without saying therefore that the school would hold to Rose’s view that “Phonic work should be set within an broad and rich curriculum” (Jim Rose, Independent review of the teaching of early reading p70, 2006) The key is to see phonics as a piece of the literacy jigsaw not the jigsaw itself.

Short, Regular, Discrete lessons

Whilst the school holds a constructivist approach to learning and generally seeks to set all learning in a meaningful context it does recognise that there are specific skills that children need to acquire and that some of these are best taught in short, sharp discrete lessons which have little context. The learning of number bonds and times tables fall into this category, as does the teaching of phonics. The reality is that these areas of learning are skill specific and will provide children with the tools to be creative in the later years of primary education. So whilst the school would agree with the recommendations in Letters and Sounds that phonics are best “taught in short discrete daily sessions ” it would also underscore the second part of the sentence that states that the curriculum should have “ ample opportunities for children to use and apply phonic knowledge and skills throughout the day (Letters and Sounds p7) .

Differentiation

There will be an obvious need for differentiation within the teaching process and this will often lead to the teacher developing a system of ability groups within the class.

Whilst this is commendable the phonics lessons should not be reduced to a carousel approach where the teacher has a focus group leaving the rest of the class engaged in potentially low level activities. The key to the success of each lesson is the child’s active engagement with a teaching professional whether a teacher or a teaching

4

assistant. The focus lessons produce the progress, the others provide consolidation at best and the educational treading of water at worse.

The Teaching of Phonics

The school holds to the view that all children should be taught phonics in the first instance but feels that the requirement in Letters and Sounds, 2003, for phonics to be taught daily “at least up until the end of year 2” is somewhat excessive. Although the rationale behind this will be spelt out in some detail later in this document, more recent research (Rhona Johnston and Joyce Watson, 2005) has found that … “Most of the letter-sound correspondences, including the consonant and vowel digraphs, can be taught in the space of a few months at the start of their first year at school.

”

To this end the expectation is that with a concerted approach to the teaching the majority of children will have established a good foundational phonological awareness by the end of the Foundation Stage and/or within the early stages of Year

1. The exception to this may be the SEN children who will continue to be supported in this area well into Year 2 and beyond if necessary; this provision will be in the form of class withdrawal where they will be taught in small, highly focused group sessions.

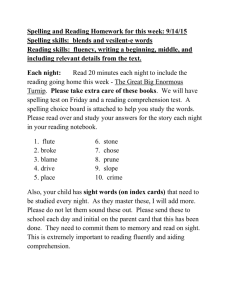

The School Pyramid and the High Frequency Words

There are two documents that will drive much of the teaching in the early years. The school’s Phonics Pyramid (see Appendix1) will allow teachers not only to assess and track each child’s progress but will also ensure appropriate continuity and progression throughout the school. Alongside this the High Frequency words should also be taught. Where possible they should dovetail into the phonics teaching e.g.

“but” could easily be taught in a cvc lesson. Others should be taught discretely elsewhere but there should be an understanding on the part of the teacher that the teaching of these words is more effective when placed in the context of the child’s own work not taught out of context. This is because they are not skills to be taught like building blocks for future learning (as are the phonic sounds) but they are stand alone words. Therefore they need a constructivist learning approach, rooted in and developed alongside the child’s own writing. Any other approach is philosophically flawed.

Blending and Segmenting

The whole basis of synthetic phonics as proposed by Jim Rose is based around the blending as well as the segmenting of the sounds. So whilst the segmenting of words maybe a strategy more akin to the teaching of spelling the use of blending should be taught alongside. One of the criticisms Ofsted had of phonics teaching when they were commissioned to undertake a study of the effectiveness of the National Literacy strategy was that “While the full range of strategies are used by fluent readers, beginning readers need to learn how to decode effortlessly, using their knowledge of letter-sound correspondences and the skills of blending sounds together. The importance of these crucial skills and knowledge has not been communicated clearly enough to teachers.

” (The National Literacy Strategy: the first four years, 2002).

The Rose review was unequivocal in its wish to see both blending and segmenting taught together and stated that … “The ‘reversibility’ of decoding letters to read words and choosing letters to spell (encoding) meant that children were applying their phonic knowledge and the skills of blending and segmenting in two contexts: reading and writing...

(and this) developed their confidence and self-esteem as readers and writers. The school would concur with this approach and develops the teaching of reading alongside the teaching of spelling through its phonics work.

5

Multi-Sensory Approach

This phrase has become an educational buzz word in recent years but this is with due cause because it is the basis for so much quality teaching. Children need to access learning through a broad a spectrum of senses as is possible in all areas of the curriculum and phonics is no different. As The Rose review says “The multisensory work showed that children generally bring to bear on the learning task as many of their senses as they can, rather than limit themselves to only one sensory pathway.

” (Jim Rose Independent review of the teaching of early reading p21, 2006)

Having said that teachers should be aware that the visual sense is the human preferred mode of learning and as children move into Key Stage 2 there will be a greater emphasis on the visual elements especially with regard to spelling. The rationale behind this will be brought out later in this document but suffice to say at this point, that good spellers can “see” words and how they are spelt more easily than their peers. It is this ability to see letter patterns and word strings that the school needs to foster within each child.

The Use of Spelling Logs

The use of Spelling Logs is a major feature of the spelling strategy deep into Key

Stage 2. As outlined below it is based on the principle that there are patterns in words that go beyond phonics and these need to be explored and imbibed. Whilst this is a central feature in the later primary years it should not prevent children, even in the Foundation Stage, from exploring words which cannot be spelt phonetically.

They should be encouraged to explore irregular words such as “knight” with its silent letter and be encouraged to search or look out for others of its ilk. This is a crucial part of the developmental process as it is encouraging children to find patterns and relationships between letters and words; this is what lies at the heart of the teaching of spelling. Such exploration will provide a rich and important foundation for the work the children will undertake later in the school.

Teaching of Spelling

Moving beyond successful Phonic Acquisition – A Key Turning Point

The time to stop teaching discrete phonics

There comes a point in the teaching of spelling when children will have acquired sufficient understanding in phonological awareness that they are able to use these skills to build up words successfully. Once a child has reached a point where he recognises that the bird’s beak may be spelt; “beak”, “beek” or “beke” the role of

“teaching” phonics has reached a natural end. The child does not require further teaching on phonics but needs to learn which one of these spellings (all of which are potentially correct) is appropriate in the context of their own writing. For this a fresh teaching strategy is required.

The teaching up until this point will probably have been based mainly around skills acquisition and taught through discrete phonics lessons with little attempt to contextualise the learning withi n the child’s own written work - except of course for the proviso that children should have “ ample opportunities for children to use and apply phonic knowledge and skills throughout the day (Letters and Sounds p7) . This strategy is no longer appropriate for the teaching of spelling in the post-phonic phase.

At this point the emphasis switches from skills acquisition to skill application and this should be explored in the arena of text based learning. The only way for the child to realise that a bird has a “beak” and not a “beek” is to root their understanding in the context of written text.

6

Much of th e school’s teaching of spelling in the past has been flawed, in my opinion, because we have tried to sustain the teaching of phonics deep into the school in an attempt to “teach” children how to spell specific words. The truth is that the child already “knows” how to spell the word; they are simply struggling to draw on the correct version within a particular context.

Our teaching should therefore focus on encouraging children to learn spellings in context and wherever possible within the context of their own writing. There is a danger that without context we will end up with children that can spell phonetically but will produce texts similar to the poem at the beginning of this document. Whilst the spelling is perfect it is only the context which establishes the errors, you will also observe that the reason why the spell checker cannot pick up the errors is because … it checks words in isolation.” (Explanation from Wikipedia website) There is a danger that the teaching of spelling, in discrete lessons, using words out of context will simply replicate the same error.

The Complexity of the English Language

Pertinent to this debate is the oft quoted fact that English is one of the most complex languages in the world to learn. English is not at its heart a phonetic language. By contrast Swahili is totally phonetically based, reading an unknown word is relatively straight forward as the word is pronounced as it is written, so “Jambo” (meaning

Hallo) is pronounced just as you might expect. In English why should “cough” be pronounced “cof” and yet “bough” be pronounced “bow” – or should that be “bow”, as in rhyming with “low”! George Bernard Shaw was once asked to pronounce the word

“Ghoti.” He replied “Fish” and when asked why he explained it as follows: the gh = f as in rough; the o = i as in women; the ti = sh as in nation.

There is no phonics lesson that can “teach” out of context i.e although bough rhymes with cow, cough rhymes with off and whilst rough rhymes with puff, though rhymes with Jo and through rhymes with too. The same applies with the frequent use of homophones in the English language with words such as sea and see; for and four; or hear and here. These complexities require teaching beyond single lessons and as

Peters points out “only the meaning and the grammar will point to the correct one of the two. The look of the word must be connected with its meaning” (Peters M 1985

Spelling Caught or taught p75)

Philip Seymour (see article in Times Educational Supplement, 7 September 2001) studied children learning to read and write in 12 different European languages. They classified languages according to both complexity of syllable structure in the spoken language and depth of orthography in the relationship between the spoken and written language. English is extreme in both respects: its syllable structure is complex, and its orthography is deep compared with a language such as Finnish which has simple syllable structure, and shallow orthography. He calculated from these finding that English-speaking children could take two to two and a half times as long to reach the same level of competence as children learning literacy in less complex languages just because of the complexities of the language.

The reality is that the acquiring of the English language is too complex to rely on discrete teaching in lessons that set no context for the meaning of words and are not grounded in the study of words within a given text. As Peters says, “simply to transfer our knowledge of sounds to spelling would be fatal… with the many words that could have quite reasonable alternatives” (Peters, Spelling Caught or Taught p 9) There has to come a point when the teaching strategy changes markedly to facilitate this new style of learning

7

When should this change in teaching strategy occur?

It is my contention that once children have acquired the basics in the phonics pyramid (see appendix 1) they should move to a more holistic based teaching strategy. As stated previously I see no reason why the formal teaching of phonics should continue for the majority of children past the early stages of Year 1. Certainly by Year 2 it is my hope that most children will be taught spelling in the context of their own writing, developing individual Spelling logs and exploring letter patterns in words for themselves.

The complexity of Spelling over Reading

This aspect may seem obvious but should not be overlooked. The school has found to date that the teaching of phonics is having a greater impact on children’s reading than on their spelling. There may be a multiplicity of reasons for this; some will hopefully be addressed in this document, but the most obvious one is that spelling

(encoding of words) is more complex than reading them (decoding). When reading the context assists the child, whereas with spelling the child starts with a blank sheet of paper. “Reading is from the unknown to the known via the context to the known.

Spelling is from the known to the unknown.” (Peters, 1985) So whilst 71% of 8 year olds can read the word “saucer” (even outside the context of the word being set within a text) only 47% of 10 year old children were able to spell it correctly. (Peters,

1985) As Reid and Donaldson (1979) point out, in reading, the child is only concerned with what the word sounds like, the unknown word is being transformed into the known meaningful sound, this is known as decoding. However spelling is encoding a familiar and meaningful sound into a strange and unpredictable code. As they state, quite correctly, “phonics for reading is not the same as phonics for spelling” In similar vein Letters and Sounds stated that “Reading and Spelling become less reversible as children start to work with words containing sounds which can be spelled in more than one way (Letters and Sounds p12) If this is the case it begs the question how we teach spelling once children have acquired the basic rudiments of phonological understanding. The remainder of this document seeks to address this question.

Teaching of Spelling

The Pedagogy for teaching Spelling beyond Phonics Lessons

What is the way forward?

Having established that the use of discrete phonics lessons is not an effective pedagogy to take children forward in their learning of spelling in the post-phonics phase the question remains as to what pedagogy the school feel should underpin the teaching of spelling in the latter part of Key stage 1 and into Key stage 2.

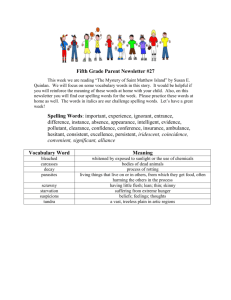

The two schools of thought

In recent years there have been two schools of thought that have dominated the spelling debate. At one end of the continuum is the traditional approach which hinges on the principle of teaching spelling in dedicated lessons. In the past these have focused on the teaching of phonic patterns and spelling rules. The evidence is overwhelming that this form of de-contextualised learning is flawed. At best it renders little impact on children’s spelling within their written work and at worse can have a detrimental on the progress of proficient spellers. “Often it is only when a rule is pointed out to a habitually good speller that doubts begin to occur.

” (Peters, p64)

Related to this is the work of Simon and Simon. They programmed computers with

200 spelling rules and then gave the same computer 17,009 words to spell, it failed in over half. Indeed when 10 year old children were tested on the words they outscored the computer. (Simon and Simon 1973) Similarly whilst the rule “i before e except

8

after c ” tends to be universally known the Associated Exam Board reported that the most frequent spelling mistakes in the 1978 O-level papers were the words “receive” and “believe” (Peters, p78)

At the other end of the continuum is the reaction to the over interventionist strategy of the traditional methods. There developed a belief that simply exposing children to a wealth of reading material and written literature would ensure that children would

“catch” spelling strategies for themselves. Needless to say, the latter strategy has proved no more effective than the former, both being philosophically flawed. Many reduced these two arguments down to a debate as to whether spelling is “Taught or

C aught.”

Critique of the two schools of thought

The evidence opposing the de-contextualised teaching of spelling is extensive and much has been stated in the sections above. Suffice to say, that learning is not about the compartmentalisation and storing of separate fragments of knowledge. The brain is a unified whole and understanding is developed as the mind makes connections on a variety of levels through active engagement with new material. Using a slightly related example, when your young child says to you “What does irascible mean?” it is incredibly difficult to construct an answer that takes in the full orb of the meaning of the word. Whilst it is true it means grumpy, it also is more than that, relating more to someone being irritable as well as snappy, although all these words don’t quite get to the true meaning, tending to skirt around it. How much easier when you know of a person who displays this characteristic to simply say “He is irascible.” The reason is that the latter creates a multi-dimensional explanation allowing the brain to instantly make a high level of multiple connections which greatly assist true understanding.

The “word shrapnel” approach is very flat and 2-Dimensional in comparison. All learning should take place in the richest and broadest of environments and the teaching of spelling is no different. So to assume that “teaching” children pockets of knowledge in isolation away from real texts will allow them to make progress is defective pedagogy.

The other school of thought sounds more promising and would on first analysis appear to support the school’s constructivist philosophy of learning. It is in essence child centred and works within the context of the child’s own work. However there is a fundamental weakness within its thinking. Let me illustrate with the following passage of text:

Rome is accessed from the sea through the port of Civitavecchia which lies 80 km North West of the Italian capital on the shores of the Tyrrhenian Sea, which in turn is part of the Mediterranean Sea.

Bearing in mind you have only just read the passage see if you can name (without referring back to the text) the port that Rome accesses for its goods and services.

The chances are that whilst you will have read the whole paragraph the reality is our mind glosses over words we don’t need to “read” to maintain the basic meaning of the text. If we don’t even “read” the text what chance do we stand of being able to spell the word. Without looking back at the text how well would you be able to spell either the port or the sea on which it sits? Having said that how many of us can spell the word “Mediterranean” without resorting to pen and paper at least? Whilst it could be argued that it was the first time you may have seen the first two words, imagine how many times you have seen and read the word “Mediterranean” and yet still the majority of adults struggle to spell it correctly.

9

The flaw in the “Spelling is caught” argument is that we “read for meaning” not to assist our spelling. If we can make sense of the text then we feel no particular compulsion to engage with the text at a deeper level – indeed why should we. Using another example; the majority of people read this infamous phrase (right) as

“Paris in the Spring.” This explains why some learned academics that are very well read do not excel in the area of spelling. The truth is that secure spellers are those who notice the patterns and forms in individual words rather than those who are well read. This simply illustrates Peters point that “Reading alone does not determine whether a child will be good at spelling.” (Peters, 1985 p16)

Further evidence is provided by a study which concluded that “Children are likely to learn to spell only 4% of the words that they read” (Nisbet, 1941) By the same token research has shown that contrary to popular opinion it is often the fastest readers who make the weaker spellers due to their inability to focus in on the structure of individual words and letter patterns within them.

For the “caught” philosophy to be effective teachers need to ensure that children are reading with a view to looking specifically at spelling and word structure. The hope that children will imbibe this as they read naturally through a range of texts is sadly lacking in its understanding of the learning process. The greater truth is that “Time spent on attention to word structure is a more powerful predictor of actua l progress”

(Peters, 1985 p17)

Keys to a Successful Spelling Programme

From my own reading I would present the following as the major philosophical drivers that should lie behind the school’s teaching of spelling. They are not prescriptive but are guiding principles. They do not seek to set out in any detail how they should be implemented in each individual class, this is the task of the classteacher, but they should underpin the practice throughout the school. a) “Invented” or “Emergent” Spelling

The use of “invented spelling” promoted by the National Writing Project in the 1980’s and now mainstream thinking was primarily to “separate the specific problem of learning to spell from the other more satisfying matter of getting on with writing” (M

Smith 1982, p187). It allows children to engage in the creativity of the writing process without being overly concerned with the secretarial aspects, allowing these areas to be addressed in the re-drafting process. Whilst the main focus may have been to promote on creativity the philosophy has been proven to have had a positive impact on spelling. Research has shown therefore that children taught in this manner not only show more enthusiasm for the writing process but have a greater grasp of spelling strategies . “Young children encouraged to use invented spellings seem to develop word recognition and phonics skills sooner than those not encouraged to spell the sounds they hear in words ” (Clarke, Invented versus traditional spelling,

1988). This is due to the fact that, in writing their own spellings they are actively engaging themselves with letter patterns and phonetic sounds. Whilst the phrase

“flying sorser” is not correct it compels children to look at how words might be constructed and encourages them to engage in, (what experts call ) “phonogrampheme divergence” or the turning of sounds into written form. In addition it also provides a powerful diagnostic tool for the teacher; in our particular case it is clear that the child has a clear understanding of the sounds “or” and “s” but has not seen that “au” can make a sound comparable to “or” and that words can use the soft “c” to

10

create an “s” sound. Wherever possible this “emergent” approach to spelling should be encouraged, as it frees children to write and impacts greatly on their ability to play around with sounds. The only word of caution is that this style of learning needs to be dovetailed into a secure marking policy for as Letters and Sounds pointed out

“Teachers should recognise worthy attempts made by children to spell words but should also correct them selectively and sensitively. If this is not done, invented spelling could become ingrained ” (Letters and Sounds p13)

The Key to Learning Spelling

The key to progressing in spelling beyond the basic phonic level is to recognise that whilst English is a complex and difficult language it does still have forms and patterns that children would do well to recognise. It is in the recognition of these that children will make the most progress. So whilst we might recognise that the words

“Clodamation” and “grhyaikht” are both nonsense words, neither of which appear in any English dictionary, we would readily recognise that the former follows linguistic conventions more closely than the latter. Wallach’s research found that “good spellers were found to recognise nonsense words resembling English much more readily than poor spellers” (Wallach 1963) It is this ability to imbibe these patterns which allows proficient spellers to make good progress. Whilst pondering this I watched my wife seek to complete a crossword over the holidays. The thought processes she undertook to solve the clue showed a clear understanding of spelling pattern. Suppose one came to a word that had the clue “type of cream” and you knew from the rest of the crossword that the solution had the letters; c _ _ _ t _ d.

You might surmise that the letter after the “c” might be an “l” or an “r”, of course you would know it would not be a “d” or an “f”. You might be aware that it could also possibly be a vowel, which it may well be. You could also deduce that there was a strong possibility that the letter preceding the final “d” might be an “e”. Then starting with a blend one would need a vowel and then maybe a double consonant, making the word “clotted”.

Such a thought process shows a clear understanding of the syntax of morphemes and graphemes in individual words. As Gibson and Levin stated

“spelling is a kind of grammar for letter sequences that generates permissible combinations without regard to sound” (Gibson and Levin, 1975) This is where we need to take children; they need to have a deep understanding of the principles that govern the make up of words.

There are two dangers attached to this. As proven earlier, just exposing children to texts will not make any impact on their ability to develop secure spelling strategies.

Reading is for decoding and as we now know children (and adults) gloss over texts to gain the meaning rather than focusing on the structure of individual words. As Peters points out “Just looking does not seem to be enough” (Peters, 1985 p32) instead we need to “direct the attention of the individual to the particular characteristics of the wordform and consolidating this in writing.” (Peters, 1985 p35) So for this strategy to be effective children need to be drawn specifically to spelling patterns and how words are constructed. Radeker (1963) found that children who were exposed to (what he termed) “imagery training” and looked at the specific structure of words “scored significantly hig her on spelling tests than did the control groups” It goes without saying that this process is best done separately from the creative process and is best tackled within the redrafting phase of the child’s writing.

The second danger is that the school reverts back to the traditional class taught or even group based lessons of teaching spelling rules where the learning (or rather the teaching) is driven by the teacher. However the reality is that children “will acquire the secret of spelling by generalisations rather than by the tedious method of learning rules.” (Peters, 1985 p44) The wording of the National Literacy Strategy document was clear in this regard. They stated unequivocally that children should “explore” the

11

patterns in words for themselves and should “identify mis-spelt words in own writing; to keep individual lists and learn how to spell them” (NLS document 1998) As Fernald found “the most satisfactory spelling vocabulary comes from the child itself” (Fernald,

Remedial techniques, 1943 p206) The key is that the child takes ownership of their own progress in the subject and that spellings and the learning of spelling patterns are drawn form the context of their own work.

All that I have read and researched leads me to believe that this aspect of getting children to actively engage with word structure is fundamental if they are to make good progress in spelling. Peters puts it as well as anyone when she says:

It is significant in this context, that time spent by teachers on attention to word structure was seen to determine actual progress in spelling. Children receiving no such teaching and children blindly pursuing a printed word list with no instruction about how to learn the words, deteriorated in their ability to write words that conformed to precedent in English. In other words, children who were not taught to look carefully at the internal structure of words did not make “good” errors” (Peters,

1985 p20-21)

An emphasis on visual learning

Some what related to the aspect above is the fact that “as humans, sight is our preferred sense; we rely on looking to check almost everything we do” (Peters, 1985 p9). To this end we should ensure that whilst our teaching should maintain an obvious multi-sensory approach there should be a heavy emphasis on the visual as the main learning approach. Most of us, if not all of us, have a preference is to “see” whether spellings are correct. How many of us as adults, once we have spelt out a word in our head have to write it down to “see” if it is right. This aspect should not be ignored, especially in the light of the comments made in the preceding section.

Children need to explore patterns and need to see them holistically.

Whilst in the past many teachers have given children spelling to copy out back into their work this should be done with some caution. It should be obvious from all that is written above that “the teacher’s job is not to correct mistakes the pupil has already made but to help them not to ma ke the mistake next time.” (Torbe, Teaching Spelling

1977) The strategy of copying out spellings can remove the visual patterning element from the process as the child reduces the task to a copying of letter by letter activity.

As Peters points out this is similar our use of the telephone directory where

“we look up a telephone number, dial the individual digits and mentally wipe out the number so effectively that if we were given the wrong number we have to look it up again”

The

Look-Cover-WriteCheck method developed in the 1980’s was an attempt to alleviate this problem and encouraged children to memorise the word as a whole rather than breaking it down into its individual constituent letters. It remains a secure, tried and tested technique and is much more preferable to the individual letter copying approach. The teaching of spelling must be as a holistic and contextualised activity where the emphasis is not upon the correction of the individual word but the creating of a rich bank of spelling patterns that will serve them well in the future.

The Use of Spelling Logs

It is only when children are motivated to pay attention to the structure of a word, to retain the perception, to overlearn and to follow practices of self testing that they are going to become good spellers (Peters, 1985 p92)

If the above is true then each child, in each class needs to be fully engaged in the process of their own learning journey. They must take ownership of it and make it their own; therefore the role of personalised Spelling logs will need to become an integral part of this process. They need to become something more than simply a storage space for the words we will take home to learn at the end of the week. They

12

need to become an active and vibrant part of the learning process for the child, which to be fair is how they were envisaged to be use within the National Literacy

Framework. (NLS) The wording of the NLS such as … pupils should explore the full range of spelling conventions and rules outlined within the strategy, e.g. What happens to words ending in “f” when a suffix is added? … make it abundantly clear that they saw the individual child with their own individual spellings as central in the learning process. Therefore teachers should reflect on how they can get children to explore ways in which they can collect, record and develop a secure understanding of the word syntax of the English language.

It may be in the light of what is written above that the traditional spelling logs ordered as they were alphabetically are not the best way forward, maybe more meaningful for the child would be pages with word patterns e.g. all the words that begin with the same prefix i.e. auto, un, or having the same suffix such as –ed. From there children could easily elucidate patterns such as the double consonant prior to the word ending. Maybe another page might contain words that have the letter pattern –ough in them; from here it would be easy to explore the different sounds that this pattern makes as well as consolidating the pattern itself.

Certainly the words the children collate in any spelling log should focus on the letter strings which they are struggling to take on board. So the word “Gleeming” would probably best be stored on an e-sound page rather than the gl- page because it is this aspect which the child is seeking to learn. The word bank project undertaken by

Cripps and Peters stressed that children should look “particularly at the highlighted letter string which is likely to be the hard spot and then look at this in the other words in the bank” (Cripps and Peters, 1978)

Teachers should also be mindful of this principle when selecting spelling errors to correct in a child’s work. However there needs to be a secure understanding in the mind of those marking the child’s writing that good spelling is the result of a child gaining a secure grasp of the syntax patterns found in words. Therefore the greatest progress will come from engaging the children with words which break the patterns of regular letter strings as opposed to errors produced by viable phonetic alternatives.

So where a child has spelt “beek” instead of “beak” but has also spelt “thuoght” wrongly, the latter should form the focus for the next stage in the child’s development. This is because t he former is “correct” in terms of phonetic sound and can be corrected through context; however the latter shows a distinct weakness in the “ough” letter string, which will hinder the future spelling of any word with this pattern.

Handwriting

Whilst this may not be a major aspect within the spelling debate it nevertheless is one which should not be overlooked. There has been much research on the relationship between spelling and handwriting, most notably by Cripps. His “Eye for

Spelling” programme is already well used in many schools and is based on the philosophy that the motor skills of writing can dovetail into the patterns for spelling.

This relates primarily to joined-writing where the joins are felt to consolidate the patterns in the spelling. There may be some truth in this; many feel on the basis of this that joined-handwriti ng should be taught from the beginning of the child’s school life. Whilst this may be a little extreme what would benefit children is the ability to form letters correctly. This would not only assist them when they move onto joinedwriting but where there is a consistency of letter formation it might help to cement the patterning of spelling into the consciousness of the child.

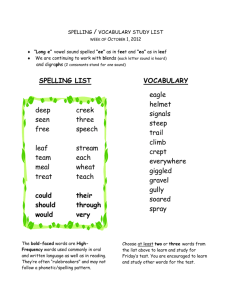

The Assessment of Spelling

The traditional approach of the weekly spelling test is held by many as sacrosanct and remains a key feature in the majority of schools. Its limitations are obvious to all,

13

in the sense that, whilst a child may be able to remember a series of spellings over a weekend for a test on Monday, the reality is that the test is one of “Short term memory retentio n” than an activity strategically focused on the principles of spelling.

This has been further confirmed recently by MRI scans which have shown that when children learn spellings for a test they are using a different part of their brain entirely from when they tackle spellings in the context of their own writing. (Brian Male, Quote from address given at The Curriculum Foundation Conference, 26 th April 2010) If spelling tests are to remain a feature of school life they need to heed Jim Rose’s advice that they should be rooted in a broad and rich Literacy curriculum. To this end the “learning” of high frequency words which children have opportunity to use readily in the context of their own work is seemingly philosophically cogent. One might also argue that the consolidation of phonetic sounds learnt that week is similarly of benefit. However the use of random spelling lists for children to learn weekly might seem at best marginally beneficial and at worse a complete waste of time. The use of words taken from t he context of the child’s own writing is a far more coherent way forward. Having said that in the light of the findings in this document, it may be that there is a more creative way in which we can use the testing of spellings to move children’s learning forward. Whilst in the early years of primary education the spelling lists may well be teacher directed would it not make more sense for children to have a greater handle on their own learning as they move into Key Stage 2. If what was quoted previously is correct that … It is only when children are motivated to pay attention to the structure of a word, to retain the perception, to overlearn and to follow practices of self testing that they are going to become good spellers… then would it not be better to get the children to select their own spellings from patterns they have found and wish to learn. Why should they not decide how many to take home, work out how they wish to be tested and how they will monitor their own progress? Maybe they could develop their own recording system where they have a set number of spellings? Grouping words around a similar pattern they might try to see how quickly they can increase the number they get right each week? They could monitor their own progress just as their progress in times tables are tracked at present. The teacher should be open to exploring new methods of making the testing process an ever increasingly effective servant of the philosophy rather than a weekly test that operates out of a sense of traditional expectation, or the lack of anything more effectual to replace it.

The Role of SEN Teaching with regards to Spelling

There will be those who, for whatever reason, struggle to imbibe the spelling patterns and structure of individual words. Whilst there is the expectation that the majority of children will be in a post-phonic phase at some point in Year 1, there will be those children who will require additional support into Year 2 and some well into Key Stage

2. Their provision should centre around the actions outlined on their Individual

Education Plan (IEP) and will be similar in provision to that offered in the Early Years; namely small group work, taught in discrete lessons with a heavy emphasis on teacher or TA interactive teaching. They may stay on a structured programme longer than their peers and be offered this intensive support deeper into the phonics pyramid than might be offered to other children. This is because whilst the majority of children will probably be able to access spelling strategies through osmosis and through the exploration of written texts, those with dyslexia may not readily make these crucial connections themselves. In this sense they will need continued support throughout their schooling until they reach a point where they are deemed to be able to learn spelling patterns independently.

Meeting the needs of the More Able

14

As with their SEN counterparts the more able children require a personalised approach if their needs are to be fully met. There will be some children for whom the teaching of phonics is somewhat superfluous as they appear to imbibe spelling patterns with relative ease. These children probably enter the years of Key Stage 2 with little need for any further phonological knowledge, little need even for a weekly test and yet there are so many areas left to explore related to the subject of language.

I once overheard a conversation between two elderly men tackling the crossword in the Daily Telegraph. One of them suggested a word for a given clue to which the other replied “It can’t be that because that word does not come from a Latin root and the Telegraph crossword only uses Latin based words” The conversation made an impact on me simply because it communicated that here were two men who had a real love of language. Whilst I use language functionally simply to fulfil commitments I have in my work environment, or my personal life here were people who appeared to have a genuine love of words and how they are constructed, formed and operate as a system in their own right.

I would contend that our enquiring and engaging children would find the whole subject of word formation, both present and historical a fascinating area of study.

I have a vision of children in the upper years of KS2 having a real love of language and of words in a way which we have not yet seen. I see no reason why children in the upper years of Key Stage 2 should not have a thorough understanding of the

English language in the fullest sense.

For instance they could:

Gain a full appreciation of how the Romance, Germanic and Slavik roots have influenced our own language.

Understanding how and why words change through history, even words which have changed in their life time such as “the web”.

How television and other media cross cultural boundaries and influences language in countries around the globe. Many of the common phrases the children use today find their origins in TV imported from the US rather than a pure

English culture

To learn patterns and conventions of spelling and explore their origins

However this would require a completely different approach to our teaching from that undertaken at present. Again this is not new, so much of this good practice is implicit in the National Literacy Strategy.

For instance the Strategy encourages children to…

Understand that vocabulary changes over time e.g. through collecting words which have become little used and discussing why e.g. frock, wireless

To define familiar words but within varying constraints, e.g within four words, then three words, then two then one and consider how to arrive at the best use of words for different purposes

Use alternative words and expressions which are more accurate or interesting than the common words (Year 4 Term 2)

Lesson Structure

This document has been written to offer pedagogical guidance rather than seeking to be prescriptive as to how this translates into good classroom practice. However there are some guiding principles which are so strongly inferred throughout and therefore for the sake of clarity it would seem prudent at this juncture to spell them out.

Foundation and Year 1

15

In the phonics teaching phase of the Foundation Stage and Year 1, there is to be a fresh emphasis on interactive group teaching. This will require the re-deployment of teaching and non-teaching staff in such a manner that there is no child undertaking low-level consolidation tasks within the phonics lesson. It may be pragmatic to tackle this as a whole Key Stage or it may be administered within the individual class setting.

Year 2 and Key Stage 2

As the children move into the post-phonics phase the teaching changes markedly from discrete phonics lessons to a style of teaching that is integrated fully into the literacy lessons of the child. The work will relate specifically to the child’s own writing and takes place in Phase 5 of the school’s writing structure. In that sense the teaching of spelling will become part of the editing process of the child’s written work.

These sessions will no longer be teacher led but the children use the feedback and marking from the teacher to explore spelling strategies and spellings pro-actively.

This will be a shift from the current practice where phonics are taught with a focus group and the rest of the class undertake low guidance activities. Indeed the carousel style of teaching we have developed over the past few years to accommodate areas of the curriculum such as phonics and Guided Reading should, in my opinion, be looked at afresh with some rigour. My own feelings are that the balance between

“quality first teaching” and classroom management is balanced in favour of the latter and this should not be the case. We have already discussed the value of placing

Guided Reading back into the framework of the literacy lesson and I am proposing that we do the same for the phonics teaching so that all the teaching of Literacy is viewed holistically not as discrete pieces of a disjointed jigsaw. These potential changes will facilitate two major changes which will, in my opinion, greatly benefit children’s learning.

Firstly it will remove from the curriculum some of the low-level consolidation activities that many of the children currently undertake. These are of minimal value simply because consolidation does what exactly what it says – it consolidates. This means that children are engaged in activities which they have previously mastered and therefore by definition learning is minimal. Also many of the activities remain essentially passive by nature, in the sense that children are often simply regurgitating in a different form, concepts they have previously learnt in a richer teaching context.

For instance the use of phonic worksheets would fall into this category.

The second benefit will be that if the children are to have their own spelling logs and are encouraged to “explore” (NLS phrase) spelling patterns for themselves they become active learners. This will provide the ownership, motivation and impetus for children to make progress intrinsically themselves rather than feeling they are being extrinsically driven by the teacher.

Conclusion

Many would feel there is a debate to be had about the importance of spelling in this increasingly informal world where the text messaging generation appears to drive a wedge between their own unique form of communication and what many call

“standard English”. This document has sidestepped that debate, not because the school believes it does not have some merit, for if writing is about communicating meaning then it is probable that such a debate has a great deal of validity, but my vision for the school is broader and wider than the single issue of how words are spelt.

16

My vision for children at The Wyche is that they will have a fascination with words and their structure. My hope is that they will have a natural interest to explore how words originate and how they develop as societies shift and change through time.

These elements of learning transcend completely the notion that all schools are mandated to do is to produce “good spellers” and leave children with something much richer – an enquiring mind and an appreciation of the richness of their native language.

17

Appendix 1

The Wyche CE School Phonics Pyramid

Step 1 – Individual Sounds s r v m l w c d y t b z g f j x ll ck

Step 2 – Double Letter Sounds ss mp lk st nk ft lt pt

Step 3 – Blends nd sp xt nt s es

Step 4 - Suffixes ed y ing sh ch

Step 5 – Special h’s th

Step 6 – Long Sounds ai ay a-e p h n ff wh ee ie oe ue igh oa ea oo y ow y ew i-e o-e qu ng ct er oo

Step 7 – Short Sounds ea ou ow oi ar ou oy a ur au er or ir aw air are ear ure eer our a i k u sk ear ur a zz o u e ld lp ly ph a e u-e i o

18

Bibliography

G Brooks Sound sense: the phonics element of the National Literacy Strategy, 2003

G Brooks, What works for pupils with literacy difficulties? 2007

Clarke, L. K. (1988). Invented versus traditional spelling in first graders' writings: Effects on learning to spell and read. Research in the Teaching of English, 22, 281-309.

Cripps C, An eye for Spelling, 1984

DFES, Letters and Sounds: Principles and practice of high quality phonics, 2003

Fernald G, Remedial techniques in basic school subjects, 1943

Gibson and Levin, The psychology of Reading, 1975

Johnston, R. and Watson, J. The effects of synthetic phonics teaching on reading and spelling attainment: a seven year longitudinal study, The Scottish Executive Central

Research Unit, February 2005.

Ehri,Linnea C. ‘Systematic phonics instruction: Findings of the National Reading Panel’.

Paper presented at the seminar on phonics convened by the DfES in March 2003

Brian Male, The Curriculum Foundation Conference, 26th April 2010

Peters M, Spelling Caught or taught, 1985

Nisbet S, The Scientific investigation of spelling instruction, 1941

The National Literacy Strategy: the first four years, Ofsted, 2002

Radaker L, The effect of visual imagery upon spelling, 1963

Reid and Donaldson Letter Links – Teacher’s Resource book 1979

Jim Rose, Independent review of the teaching of early reading, 2006

Smith F, Writing and the writer, 1982

Philip Seymour, University of Dundee; article in Times Educational Supplement, 7

September 2001, p.4; Seymour, Aro and Erskine, 2003,

Torbe, Teaching Spelling, 1977

C. Weaver, L. Gillmeister-Krause, & G. Vento-Zogby, Creating Support for Effective

Literacy Education (Heinemann, 1996).

Wallach M. Perceptual recognition of approximation to English in relation to spelling achievement , 1963

19