Technology-Integrated Solution

advertisement

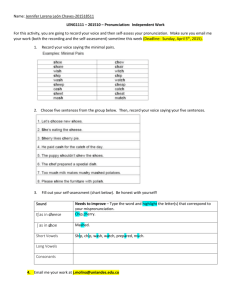

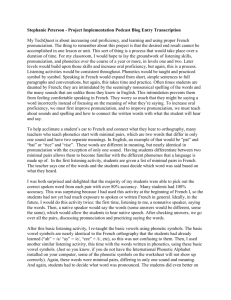

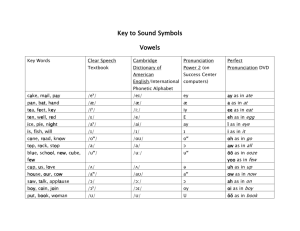

TechQuest Stephanie Peterson The Problem of Practice and Setting There are many aspects to learning a foreign language. Acquisition of vocabulary, knowledge of grammatical rules and structures, and learning about cultural norms and traditions are all important parts of the process. However, there is another aspect that teachers often neglect and leave on the backburner, and that is pronunciation of the target language and oral proficiency. Why is pronunciation and oral proficiency important? Students often begin learning a foreign language with their peers (most of whom are also lacking in experience with the FL), and regardless of mispronunciation, they are usually understandable to the teacher and class. However, at some point, a student may find himself or herself in a face-to-face interaction with a native speaker. If the student has not learned proper pronunciation and is not orally proficient, he or she could be incomprehensible to the speaker. Communication cannot happen. And quite frankly, that would negate the whole purpose of speaking in the first place. We all want to be understood when we speak, and proper pronunciation allows for that. It is important to discuss to what level of oral proficiency a student should have realistically achieved after completing a high school study of French. In a study by Isabelle Drewelow and Anne Theobald of the University of Wisconsin – Madison, they found that the previously held belief that native French speakers had low tolerance for an American accent in French was false. They argued that it is therefore necessary for language instructor to “refrain from misinforming their students that a perfect native-like pronunciation is vital to successful communication with native speakers.” 1 I find this argument to be slightly ironic. Achieving perfect, native-like pronunciation is nearly impossible for a non-native speaker after a certain age. In fact, I would argue that in most schools, there is not enough focus on correct pronunciation in general, much less on “perfect, native-like pronunciation.” However, the important thing to remember is that the goal is not perfect pronunciation, but comprehensible pronunciation. After studying French in high school, for whatever length of time, but increasingly so in the more advanced levels, a student should be speaking French in such a way that he or she would be comprehensible to a native speaker. We must also discuss why a teacher might neglect teaching students about proper pronunciation. For this project, I will focus specifically on learning French, for some reasons I must explain. Most Spanish teachers do spend quite a bit of time teaching students about Spanish’s 5 vowels, which are always consistent and are always pronounced. The orthography matches the pronunciation nearly 100% of the time. However, French has over 16 vowels, many of which do not exist in the English language. In French, orthography does not match pronunciation, for example the letters “eau” make one single vowel sound “oh”. There are many pronunciation rules and also many exceptions to the rules. It can be confusing for students and teachers alike. A teacher cannot teach proper French pronunciation unless his or her own pronunciation is strong, which is often not the case. Many teachers write off teaching pronunciation due to this confusion and difficulty, and instead justify it with the explanation that the student will learn proper pronunciation in college or when the student visits the country or completes a study abroad program. In this project, I will explore how a teacher might use technology such as podcasting to teach pronunciation and oral proficiency. The goal is for students to be able to make French sounds correctly, to connect orthography to those sounds, and speak with a comprehensible pronunciation and accent. Technology-Integrated Solution In order to improve pronunciation and accent, students must also have a phonetic reference point, i.e. the students must listen to examples of good pronunciation and attempt to analyze and mimic that. This explains why students with weak pronunciation tend to have been taught by teachers with weak pronunciation. However, although a non-native teacher with strong pronunciation is a good place to begin, students must also hear examples of native speech. The audio exercises that accompany most French language textbooks are out of date, scripted, and boring. They often do not reflect authentic speech, and students are not motivated to listen to them. Therefore, the first step in improving a student’s pronunciation must be to provide the students with authentic, engaging speech. The technology that can greatly help this first step would be podcasts. In the fall of 2004, Duke University gave each incoming freshman an iPod. Although they reported a number of benefits in general from this program, what is most interesting for this study is how the foreign language classes took advantage of the iPod technology, and what they did with podcasts. They would listen to authentic materials in the target languages such as news, song, music and poems. The instructors would create podcasts in the target language of vocabulary, lectures, and to give oral feedback to the students. Students could also create their own podcasts to respond to verbal quizzes, submit audio assignments, and record audio journals. Among the general benefits, Duke reported a greater student engagement and interest, and enhanced support for individual learning preferences and needs. 2 If one should go into iTunes and search for French language podcasts, a plethora of options would be available, created by everyone from teachers to students to native speakers, in every level and on every topic imaginable. Many of these podcasts are educational, and the some creators even provide lesson plans and worksheets that go along with their podcast. Podcasting allows students to listen to authentic, engaging audio that is likely more relevant and therefore more able to hold their interest than any audiotape a book publisher can come up with. And downloading podcasts is EASY. You can set up iTunes to automatically subscribe to a podcast and download the newest episodes as they become available. A teacher can then play the files straight from the computer, or burn them onto a CD to use on a player in the classroom. The same thing is true for students. iPods have truly infiltrated our culture, and it’s hard to find a teenager without one, or some version of one. The students can download the files on their iPods at home and listen to them for homework or just for fun. As Steve McCarty from the Osaka Jogakuin College in Japan (which was actually the first school to provide iPods to students, even before Duke) explains, “podcasting takes the next step of pushing sound files to subscribers with portable MP3 players such as the iPod for listening on the go. This opens up new educational potential in terms of using hitherto unproductive time for learning.”3 Once a student has acclimated their ear to the French language, and can hear the different sounds, intonation, and accent, they will be better able to pronounce the language correctly themselves. After sound acclimation, students can begin to reproduce the sounds themselves. Repetition is necessary, but CORRECT repetition is key. If the students do not learn the correct pronunciation of a word in the beginning, they can create a bad habit of always mispronouncing it, and habits are difficult to change. It is important that the teacher not let the student continuously mispronounce words, but in a sensitive manner, so that the student does not feel discouraged from speaking. A difficulty in teaching oral proficiency is the fact that speaking takes time, which is difficult to find during the regular school day. A teacher cannot conceivably work with each individual student on his or her pronunciation during the regular class period. However, with the right technology, each student can create his or her own brief audio file or podcast to which the teacher can listen and provide commentary and correction. A student can save each of these files and witness their improvement from each podcast to the next. In order to do this, a teacher and student would need access to a computer, a headset with microphone, and audio recording software such as Apple’s Garage Band or the free open-source application Audacity. Those without access to a home computer or headset can use Gcast.com, a website which allows people to create podcasts using a telephone. Implementation and Findings *link to worksheets* This project is about increasing oral proficiency, and learning and using proper French pronunciation. The thing to remember about this project is that the desired end result cannot be accomplished in one lesson or unit. This sort of thing is a process that would take place over a duration of time. For my classroom, I would hope to lay the groundwork of listening skills, pronunciation, and phonetics over the course of a year or more, in levels one and two. Later levels would build upon those skills and increase oral proficiency, but again, this is a process. Listening activities would be consistent throughout. Phonetics would be taught and practiced symbol by symbol. Speaking in French would expand from short, simple sentences to full paragraphs and conversations, but again, this takes time and practice. Often times students are daunted by French; they are intimidated by the seemingly nonsensical spelling of the words and the many sounds that are unlike those they know in English. This intimidation prevents them from feeling comfortable speaking in French. They worry so much that they might be saying a word incorrectly instead of focusing on the meaning of what they’re saying. To increase oral proficiency, we must first improve pronunciation, and to improve pronunciation, we must teach about sounds and spelling and how to connect the written words with what the student will hear and say. To help acclimate a student’s ear to French and connect what they hear to orthography, many teachers who teach phonetics start with minimal pairs, which are two words that differ in only one sound and have two separate meanings. In English, an example of that would be “pat” and “bat” or “rice” and “rise”. These words are different in meaning, but nearly identical in pronunciation with the exception of only one sound. Having students differentiate between two minimal pairs allows them to become familiar with the different phonemes that a language is made up of. In the first listening activity, students are given a list of minimal pairs in French. The teacher says one of the words and the students must decide which word was said based on what they heard. I was both surprised and delighted that the majority of my students were able to pick out the correct spoken word from each pair with over 80% accuracy. Many students had 100% accuracy. This was surprising because I had used this activity at the beginning of French I, so the students had not yet had much exposure to spoken or written French in general. Ideally, in the future, I would do this activity twice: the first time, listening to me, a nonnative speaker, saying the words. Then, a native speaker would say the words (some answers would be different, some the same), which would allow the students to hear native speech. After checking answers, we go over all the pairs, discussing pronunciation and practicing saying the words. After this basic listening activity, I re-taught the basic vowels using phonetic symbols. The basic vowel symbols are nearly identical to the French orthography that the students had already learned (“ah” = /a/ “ay” = /e/, “eee” = /i/, etc), so this was not confusing to them. Then, I used another similar listening activity, this time with the words written in phonetics, using these basic vowel symbols. (Just so you know, if you do not have the International Phonetic Alphabet installed on your computer, some of the phonetic symbols on the worksheet will not show up correctly). Again, these words were minimal pairs, differing in only one sound and meaning. And again, students had to decide what word was pronounced. The students did even better on this activity than on the previous one. I believe the reason for this is that writing a word in phonetics simplifies the “spelling”. Many words in French contain numerous vowels which may only be pronounced as one sound. For example “eau” is pronounced “oh” or /o/. A beginning language student would see these three consecutive vowels and most likely be confused about how to say the word correctly. Phonetically “eau” is written as one symbol, /o/, which is far simpler to understand, pronunciation-wise. Again, a change I would like for this exercise would be the addition of speech from a native speaker. The important lesson students learn from minimal pairs is how important pronunciation is. Mixing up a single sound can change the entire meaning of a word. For example, a preferred example is the two phrases “J’ai pu” and “J’ai poux.” These two phrases differ in only one vowel sound, but have two very different meanings. “J’ai pu” means, “I was able”, whereas “J’ai poux” means, “I have lice.” Imagine the confusion that could arise if the wrong vowel was used! Obviously this is just the first of many exercises and activities used to familiarize students with spoken French. The students would go on to learn additional phonemes, and how to string them together from monosyllabic words to full paragraphs. In addition, they would learn how those phonemes relate to orthography and vice versa. Although there are, of course, exceptions to every rule, the important thing is that students understand how the spelling connects to the sounds they hear and say. Once they have this down, their pronunciation is greatly improved, as is their oral proficiency. Implications I would approach this kind of project differently in the future mostly in terms of research. This project was centered on podcasting and oral proficiency, and while I could find resources about podcasting or papers about oral proficiency, it was difficult to find “scholarly” articles about using podcasting to facilitate oral proficiency. It could be because podcasting is still somewhat of a new technology, and certain areas of academic are unwilling to learn and use new technology in their teaching. I would have searched for more examples of teacher blogs, websites, and wikis, to see how real-life foreign language teachers are actually using this technology in their class. For projects concerning technology, MSU’s article and journal searches were quite fruitless. They are wonderful for finding books, scholarly articles, and academic journals. But with technology, being so new…it would be more effective to find papers from technology conferences, articles from magazines such as Technology & Learning, and search other resources. The important part of this project is that it is an ongoing endeavor. Pronunciation and oral proficiency are extremely important to me, and finding ways to teach it and improve upon it are always going to be apart of my job. And of course I believe very strongly in the many benefits of podcasting to support learning, so I’m going to be looking for more ways to integrate and use that. Although I only implemented a small part of our project, I plan to do more in the future. 1 Isabelle Drewelow, Anne Theobald. (2007). A Comparison of the Attitudes of Learners, Instructors, and Native French Speakers About the Pronunciation of French: An Exploratory Study. Foreign Language Annals, 40(3), 491-520. 2 George.M. Chinnery. (2006). Going to the MALL: Mobile Assisted Language Learning. Language Learning and Technology, 10(1), 9-16. 3 Steve McCarty. (2005). Spoken Internet to go: Popularization through podcasting. JALT CALL, 1(2).