CASE STUDY 12 : ROCK CLIMBING

advertisement

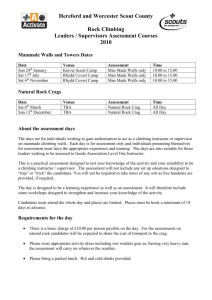

CASE STUDY: ROCK CLIMBING Rock climbing is a unique sport that has grown in popularity in recent years due to a combination of advances in climbing equipment and techniques, changes in consumer behaviour, the increasing trend towards activity holidays and the arrival of new climbing destinations around the world. Rock climbing is probably the most recognised type of climbing. This involves systematically ascending sections of rock. It requires specialist equipment for protection and knowledge of climbing techniques. The aim is rarely to get to the top of a mountain, but to simply complete the climb, which can be of any distance or duration. (Mintel, 2000) There are various different types of rock climbing that test both the mental and physical skills of the individual (see Exhibit 1): Exhibit 1: Different types of outdoor rock climbing Rock climbing types Bouldering Top rope climbing Traditional climbing Sport climbing Main characteristics Involves climbing easy to difficult movements on rock at a relatively safe distance from the ground without the use of ropes, harnesses and other equipment. Watts (1996) suggests that it is the purity of bouldering that appeals to its participants as it concerns just the individual and the rock and rock shoes. An anchor system for the rope is set up before climbing begins, usually from the top of the crag. This is usually one of the main types of climbing in indoor climbing walls. Involves one person leading up the climb placing protection en route and setting up an anchor at the top of the climb/pitch. Various devices/protection are placed at suitable points in the rock and attached to the rope – in turn attached to the leader's harness – to protect the leader should he/she fall during the climb. The seconder, or leader's partner, takes the protection out as he/she follows up the route. Involves the use of anchors (usually steel bolts) that have already been set up. These are permanently fixed on the route for the climber to clip the rope into. The climber therefore does not need to place protection whilst climbing and can concentrate on the different moves of the climb. Rock climbing originally evolved from mountaineering – a sport in which its participants used climbing skills and techniques to reach the peaks of mountains. The sport began to gain prominence from the early 1900s onwards as safety equipment was introduced and the climbing community started to evolve. A combination of developments accelerated the growth of the sport during the 1960s, such as the introduction of lightweight climbing boots, better equipment design and artificial climbing aids (Journal Of Sport Behaviour, 1998). The supply and demand for rock climbing In recent years, the sport of rock climbing has carved out a growing and significant niche within the realm of adventurous activities. The sport has not only become a popular recreational activity, but has also formed the main element of some people's activity holidays. On a general note, changes in consumer behaviour leading to more active lifestyles (hence increased participation in sports and the great outdoors) have undoubtedly had a positive impact on the growth of rock climbing. Mintel (1999) notes a steady 10% growth in UK demand for domestic and foreign activity holidays from 1994 to 1999. Activity holidays are defined as ‘holidays in which the main purpose of the holiday, or trip away from home, is a sporting or otherwise physically activity holiday’. (Mintel, 1999). It should be noted that there is a deficit of statistical data on accurate demand patterns for rock climbing though there are numerous sources from which assumptions can be made. A useful indicator of increased market demand is the growth of indoor climbing walls – artificial facilities that attempt to simulate outdoor climbing environments and are used mostly outside the main climbing season. Generally these walls attract climbers of all abilities and appeal to novice climbers because of the safe environment they provide as well as expert climbers who are keen to train in a structured regime. Mintel (2000) states that there are approximately 233 indoor climbing walls within the UK and although exact figures are not available, some of the larger, nationally renowned walls attract between 20,000 to 30,000 user visits per year. The British Mountaineering Council (BMC) have generated an indoor climbing wall directory comprising approximately 250 centres located in England, Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland and Eire (BMC, 2001). These figures alone do not demonstrate definitive proof of the rising popularity of rock climbing. Nevertheless, this figure combined with technological wall developments provides some evidence of the sport's growth, in the UK at least. Before 1985 most walls were fairly basic. Between 1985 and 1991, many walls became much more lifelike and enjoyable to climb on, and since 1991, the advent of bolt on holds has provided the opportunity to change routes and constantly adapts facilities to improve already high quality wall surfaces. (BMC, 2001:2). The 1996 General Household Survey (see Mintel, 2000) conducted on the UK population also reveals that rock climbing is increasingly being adopted as a sporting activity. In 1996 participation rates stood at 4% of men and 2% of women. This figure rose to 5% for both sexes in 1999 (Mintel, 2000) illustrating not only the rise in the popularity of rock climbing but also the equal participation of men and women. In relation to the UK market, mainly younger people participate in rock climbing: Climbers are predominantly drawn from a younger age group and tend to stop participating after leaving school/university. They usually take part as a member of a club and the main motivations are to keep fit and enjoy the social side of club-based activities. (Mintel, 2000) It has been recognised that readily available data on the demand for recreational rock climbing is limited. Likewise, a number of obstacles exist that make it problematic to obtain an accurate estimate of demand for rock climbing holidays. First, individuals who engage in climbing for purely recreational rather than tourism purposes are difficult to separate. Second, although it is possible to obtain some useful information on demand patterns from sales of climbing guidebooks, groups of people may purchase a book between them or alternatively, buy both editions of the same book. Third, in relation to the UK market, the majority of people who go on rock climbing holidays tend to make their own travel arrangements and put their own itinerary together with the use of climbing guide-books. This preference for independent holidays could be because of the image that climbers want to portray of themselves, ‘climbers like to be, or be seen to be, not tourists’ (Craggs, 2001). Notwithstanding this apparent pattern of DIY climbing holidays, a number of UK specialist outdoor activity operators offer rock-climbing holidays, indicating some demand for packaged trips, although this level of demand has remained static from 1994 to 1998 (see Exhibit 2): Exhibit 2: Specialist walking and climbing holidays by the British in the UK, 1994 and 1998 Activity Holiday Trips (m) Short 1–3 nights (m) Long 4+ nights (m) 1994 1998 1994 1998 1994 1998 *Walking 2.5 2.0 1.2 1.0 1.3 1.0 **Climbing 0.6 0.6 0.3 0.3 0.3 0.3 Total 3.1 2.6 1.5 1.3 1.6 1.3 * = hiking, hill-walking, rambling, orienteering ** = mountaineering, rock climbing, caving, abseiling, potholing (Source: adapted from Mintel (2000)) Examples of operators offering climbing holidays are Acorn Activities, Bearsports Outdoor Centres, Christian Mountain Centre, Twr-y-Felin Outdoor Centre (Mintel, 2000). These operators tend to offer multi-activity holidays, which encompass some climbing instruction, or holidays that focus solely on developing rock climbing skills and techniques. Foundry Mountain Activities (FMA) is a Sheffield (UK) based organisation that has operated mountain holidays, activities and courses throughout the world since 1991. Most of its rock climbing courses take place in the Peak District national park (see table below) and are aimed at all levels of climber: The courses aim to provide you with the skills and judgement needed to confidently become an independent climber. Your time will be spent with our rock team, qualified mountaineers who teach climbing regularly and have a passion for the activity. Whatever your level of experience it is our aim to offer the next step. (FMA Great Adventures holiday brochure, 2001) The benefits of taking a packaged holiday with a specialist outdoor activity operator like FMA are evident. The price paid for a package trip with the FMA would include: instruction by a qualified and experienced guide; supply or hire of specialised equipment; land travel; health insurance; accommodation and leadership arrangements. Additionally, the organisation aims to match personal experience and aptitude with adventurous goals, and join individuals together with like-minded people (FMA Great Adventures holiday brochure, 2001). Exhibit 3 : Foundry Mountain Activities – climbing courses and holidays FMA rock climbing courses and holidays First Steps Rock Weekend Description of FMA courses & holidays Rock Skills Weekend For people with some climbing experience, this course introduces all areas of single pitch rock climbing (e.g. placing protection and selecting appropriate routes) Outsider Starter Weekend This course is held in early spring and is aimed at reintroducing people to outside rock climbing. Peak Rock Week A comprehensive introduction to climbing that may result in novice climbers leading routes at the end of the week. Snowdonia Rock Week For climbers with some experience, this course focuses on long, multi-pitch climbing. Single Pitch Award (SPA) This course involves training and/or assessment for the SPA, an award required for group supervision of novice climbers on single pitch crags. Picos de Europa, Spain This trip involves single and multi-pitch climbing as well as a 300m ascent of El Naranjo de Bulnes, otherwise known as the Matterhorn of Spain. Costa Blanca, Spain This holiday offers climbing in a range of environments – valley crags, sea cliffs and mountain routes. Introductory course aimed at first time climbers. (Source: adapted from FMA Great Adventures holiday brochure (2001)) In addition to the specialist activity operators that run climbing courses and holidays, two National Centres in the UK have been established to ‘encourage excellence in climbing sports’ (Mintel, 2000). One of these centres is the Plas-y-Brenin National Mountain Centre in Wales and the other is in Aviemore, Scotland. Rock climbers’ behaviour People who engage in adventure recreation or tourism are diverse groups of individuals who are driven by different goals. Accordingly, rock climbers are a heterogeneous group who seek out non-uniform experiences and span across the whole hard-soft adventurer spectrum. However, it is fair to suggest that most rock climbers would be motivated by a certain degree of risk and excitement. At the hard end of the scale, big wall climbing up the famous El Capitan in Yosemite National Park whilst bivvying out on diminutive rock ledges en-route would appeal to only the most experienced and committed of climbers. This typology of climber would be seeking the ultimate in challenges, coping with the potential risks and dangers associated with leading routes whilst battling against the elements. In contrast, the soft adventurer may prefer to concentrate efforts on indoor climbing walls for the purposes of maintaining fitness levels and participating in an activity that is adrenalineinducing in a safe environment. Mintel (2000) devised two broad categories of UK climber, though it is important to note that these typologies include a diverse range of climbing activities – namely rock climbing, bouldering, abseiling, ice-climbing, winter climbing, soloing, mountaineering, potholing, caving and climbing walls: Club climbers are keen to participate in anything that is challenging and exhilarating. They are aged 15–19, male or female and are drawn from all socio-economic groups. They participate on a fairly regular or occasional basis, nearly always as part of a club that is affiliated to their club or university. Activity and outward-bound holidays are popular with club climbers, and they enjoy the social benefits of being part of a club. The opportunity to relax and unwind does not come into the reasons for participating. They participate because they enjoy the challenge of the great outdoors and meeting other people with similar interests.' Advanced climbers are aged 20–34, male or female, and are grown up climbers. They will usually have been introduced to climbing at an earlier age through school, university or friends, and will have been 'bitten by the bug'. Although they probably don't participate as often as they would like to, they do not let any opportunity pass them by. They may be at either a pre-family or family life-stage and are likely to be in a managerial or professional position at work. Advanced climbers try to maintain participation in their chosen activity despite the demands on their time from work, family and friends. A small percentage of advanced climbers will take their sport very seriously and could seek employment in this area to bring them closer to the heart of shaping the future of their activity. Climbing magazines such as On The Edge, The Great Outdoors, Climber and High Mountain Sports frequently extol the sensations that rock climbers enjoy or otherwise. Similarly, organisations promoting rock climbing courses use the perceived benefits associated with this activity as a marketing tool: Once you've tried it, you're hooked. The intrinsic rewards that come from combining concentration, agility, balance, strength and judgement are unequalled in any other sport. Nothing heightens the senses more than the combination of delight and relief that comes from reaching the top of a demanding route. Whatever standard you climb at, from novice to expert, these feelings remain the same. The key lies in seeking out new and exciting challenges. (Plas-y-Brenin National Mountain Centre, 2001) To date there has only been a limited amount of research on the psychological attributes of rock climbers and most studies to date have concentrated efforts on ascertaining the physiological characteristics of climbers. Whilst such findings are useful in discovering the biological factors affecting climbing performance, they fail to provide an insight into what drives people to climb. The few studies that investigate climbers' behaviour tend to apply psychological models in an attempt to discover a relationship between people's personality traits and their participation in rockclimbing. For instance, Morgan's (see JOSB, 1998, p.178) study on climbers of varied ability found that as rock climbing is such a unique, high-risk sport, its participants have a ‘more extreme psychological mindset’ and exhibit an ‘iceberg profile’. Such a profile is defined as ‘a model of mental health deemed necessary for optimal performance’ (JOSB, 1998, p.170) and is characterised by higher levels of vigour and lower levels of tension, depression, anger, confusion and total mood disturbance than participants of other less risky sports. Craggs (2001) comments that rock-climbing is part of his life and is addictive because of its adrenaline inducing qualities. The ability to control this adrenaline when faced with a dangerous situation contributes towards a rewarding rock climbing experience and ‘a high like nothing else I'll ever know’. For Craggs, such potentially hazardous circumstances arise only whilst on highly graded traditional routes where ‘you've got to stick your neck out’. Some of the climbs he has accomplished have evoked overwhelming feelings: In the past I've done climbs when I've come down off a route and I've not climbed for another week because you feel so good you don't need to do it again. 'Déjà vu' for example, a route where you really are in danger of death I suppose, but because you keep it together, you're not panicking, you're not flapping, you're just in control. Such feelings of exhilaration combined with the periods of great calm and happiness he encounters on certain climbs can be ascribed to Maslow's (1976) ‘peak experience’ as well as Csikszentmihalyi's (1992) ‘optimal experience’and ‘state of flow’ (refer to ‘Consumer Behaviour’ chapter for further information). To conclude, this case study illustrates a number of important aspects about the adventure sport, rock climbing. The technicalities of the sport and its differing appeal to both soft and hard adventurers are highlighted. Estimates of the growth in demand for rock climbing, both as a recreational activity and as an integral part of the holiday experience, are provided. The lack of statistical data concerning trends in climbing does however impede an accurate assessment of current and future demand patterns for this sport. Discussion also focuses on the climbing consumer and it is evident that climbers are a heterogeneous group of people who exhibit similar behaviour to many other types of adventure tourist.