Demographic Ageing

advertisement

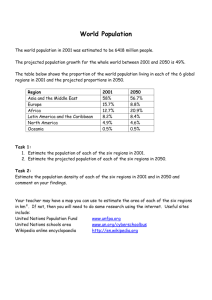

Demographic Ageing Abstract The world’s population is ageing significantly. Today, one in ten people is over the age of 60, but this proportion will double to one in five by 2050. At present, 600 million people around the world are aged 60 years and over. This is projected to increase to 1 billion by 2020 and to reach almost 2 billion by 2050. Governments are going to have to make some very difficult decisions to cope with this major trend. Global trends The problem of demographic ageing has been a concern of MEDCs for some time, but it is now also beginning to alarm LEDCs. Although ageing began later in LEDCs, it is progressing at a faster rate. This follows the pattern of previous demographic change such as declining mortality and falling fertility, where change in LEDCs was much faster than that previously experienced by MEDCs. For example, Figure 1 shows the significant projected decline in the support ratio for the world as a whole and for a number of individual countries. Figure 1 – Support ratio forecasts (ratio of 20–64 year olds to 65+). Demographic ageing is the result of (a) increasing life expectancy and (b) declining fertility, with the former being the most important of the two factors. Projections to 2050 show a considerable increase in global life expectancy from 1950, with a narrowing gap between MEDCs and LEDCs over time. The following factors have been highlighted by the United Nations: The global average for life expectancy increased from 46 years in 1950 to nearly 65 in 2000. It is projected to reach 74 years by 2050. The global median age for males is currently about 26 years, but this is projected to rise to 35 years by 2050. In LEDCs the population aged 60 years and over is expected to quadruple between 2000 and 2050. The proportion of the population over 60 years will increase from 8% to 21% by 2050. During the same time period the proportion of children will fall from 33% to 20%. In MEDCs the number of older people was greater than that of children for the first time in 1998. By 2050 older people in MEDCs will outnumber children by over two to one. The population aged 80 years and over numbered 69 million in 2000. This was the fastest growing section of the global population, and is projected to increase to 375 million by 2050. Europe is the ‘oldest’ region in the world. Those aged 60 years and over currently form 20% of the population. This should rise to 35% by 2050. Japan is the ‘oldest’ nation, with a median age of 41.3 years, followed by Italy, Switzerland, Germany and Sweden. Africa is the ‘youngest’ region in the world, with the proportion of children accounting for 43% of the population today. However, this is expected to decline to 28% by 2050. In contrast, the proportion of older people is projected to increase from 5% to 10% over the same time period. There are already over 50 nations with total fertility rates at or below 2.1 (replacement level). By 2016 the UN predicts there will be 88 nations in this category. Demographic ageing poses considerable problems to both MEDCs and LEDCs with regard to the allocation of scarce resources. However, it is the LEDCs which face the greatest challenge because: Financial, health, housing and other resources are woefully inadequate to meet the increasing demands of the elderly. Traditional support systems for old people are deteriorating in an era of rapid social change. The significant decline in fertility is leaving fewer children to care for elderly parents. Figure 2 shows how substantially the population structure of LEDCs is projected to change by 2050. However, this is not to underestimate the considerable adjustments required in MEDCs to cope with population ageing as illustrated by the case study of the UK which follows. Figure 2 – Population pyramid for LEDCs (1998 and 2050 projected). The challenge facing the UK: changing dependency ratios Demographic ageing appears to be one of the greatest challenges facing the UK today as the contrasting population pyramids for 2002 and 2050 show (Figure 3). This process is the product of rapidly increasing life expectancy and low fertility. The combination of these two major demographic trends will see almost a doubling of the population aged 65 years and over by 2050, with both men and women expected to live, on average, 10 years longer than in 1950. The post-war baby boom has delayed the effect of underlying long-term trends, but will now produce 30 years of significant increases in the dependency ratio. The post-war baby boom resulted in an increase in the fertility rate from the mid-1940s to the mid-1960s. As the children born during this period grew up and joined the economically active population, the dependency ratio was depressed to a lower level than its long-term trend. To a certain extent the baby boom’s impact on the dependency ratio has lulled the UK into a false sense of security, delaying difficult decisions concerning pensions and retirement. Figure 3 – Population pyramids for the UK (2002 and 2050 projected). The total dependency ratio is the sum of the youth dependency ratio and the old-age dependency ratio. While youth dependency has been falling, old-age dependency has been rising. The latter is projected to overtake the former in around 2025 and then to increasingly exceed it (Figure 4). Figure 4 – Old-age, youth and total dependency ratios. The Government Actuary’s Department (GAD) in its most recent biennial review (2003) projects that: The ratio of people 65 years and over to those in the 20–64 age range will rise from 27% today to 48% by 2050. This marks a considerable change from the very slow increase in the last 20 years. Average male life expectancy at 65, which has risen from 12.0 years in 1950 to 19.0 today, will increase further to 21.0 by 2030 and 21.7 by 2050. Female life expectancy at 65 is higher, although increasing at a slightly slower rate. The current low fertility rate of 1.7 children per woman will increase only slightly to 1.75 by 2022, levelling off at this point. However, it is important to note that past official projections have significantly understated subsequent developments and that this could possibly be the case for the most recent projections. In 1981, GAD projected that by 2004 male life expectancy at 65 would be 14.8 years as opposed to the actual figure of 19.0 years. Life expectancy is influenced by socio-economic class. Men in social class 1 have about four years’ higher life expectancy at 65 than men in social class 5. Thus, longevity is greater in more affluent parts of the country. Christchurch in Dorset is the ‘pensioners’ capital’ of the UK, with one in three residents being of retirement age. However, it is not just coastal areas, with a perceived high quality of life, that attract retirees. There is also clear evidence that the growing elderly population is migrating to the countryside. Age structure varies considerably by ethnic group. White Irish and White British have the highest proportions of their populations aged 65 and over, with approximately 20%, while the Black African population has the lowest proportion of older people, with approximately 2%. Low fertility and falling child dependency The birth rate in the UK, in common with most MEDCs, has fallen below the replacement level. The total fertility rate in England and Wales is now 1.7 children per woman, and despite a slight increase in 2003 it shows no signs of a significant increase in the future. The ratio of children to the working age population has fallen considerably in the last 20 years. This has been so significant that the total dependency ratio has actually fallen and at present it is at its lowest level for 40 years. As the recent GAD report states: ‘The working population in 2004 supports a historically very low burden of nonworking pensioners and children. The size of that burden, if average retirement ages remain unchanged, will now rise significantly.’ In 2001 the crude birth rate for the UK was 11.4 per 1000, the lowest ever recorded. This resulted in 669,000 births during that year, 38% fewer than 100 years earlier. The particularly low number of births in recent years is due to two factors: (a) lower fertility rates and (b) fewer women entering their peak reproductive years than in previous decades, a result of the smaller numbers of women born in the 1970s. The total fertility rate in 2001 was 1.63, down from 1.81 in 1991. Ageing and health An ageing population places increasing pressure on health resources. However, it is important not to overstate this impact. While average health care costs rise with age, the cost of this trend could be significantly offset by people getting healthier. The trend is towards the compression of illness into the last years of life, a process which has been termed ‘the compression of morbidity’. Mobility data published in Living in Britain (Figure 5) show a considerable decrease in the number of people aged over 80 facing difficulties with mobility. According to the government report Pensions: Challenges and Choices, ‘International comparisons also suggest support for the health ageing hypothesis’. The recently established English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA) will provide much more comprehensive information on the relationship between ageing and health, but not for some time. American studies show that people who are healthy at 70 and live independently for many years total up medical costs that are similar to those people who are very ill at 70 and die earlier. Figure 5 – Trends in immobility, by age. The impact of immigration on the dependency ratio Only a very high rate of immigration would have more than a very small impact on the projected dependency ratio. It would require net inward migration at over 300,000 per year to reduce the 2040 old-age dependency ratio from 47.3 to 42.1 years. However, this would only have a temporary impact unless even higher levels of immigration continued in later years or unless immigrants maintained a higher birth rate than the general population. This is because immigrants themselves age and become pensioners who require economically active people to support them. The impact of ageing on the sex ratio Because women have a higher life expectancy than men, as the population ages the number of women to men (the sex ratio) increases. Eastbourne, a popular retirement centre, has the least men to women (87:100). Financing an ageing population Pension systems transfer resources from the current generation of workers to the current generation of pensioners. As the population has aged, the level of resource transfer required has increased. The system cannot be sustained in the future without significant change. The four options available are: 1. Pensioners will become poorer relative to the rest of society. 2. Taxes/National Insurance contributions devoted to pensions must increase. 3. The savings rate must rise. 4. Average retirement ages must rise. A government survey (Figure 6) shows the preferred public responses to the pensions issue, with the majority of people expecting to either work beyond the current retirement age or to save much more each month for their retirement. The option of lower pensions is the least attractive, according to the survey. Because of increased life expectancy and thus a much higher pension bill, significant changes have either been made or are in the pipeline for both private sector and public sector pensions. Figure 6 – Preferred responses to the demographic challenge . Figure 7 shows how economic activity rates decline for the over 50s. There can be little doubt that these profiles will be significantly different in 20 years’ time with people working to a more advanced age before they retire. Figure 8 shows the estimated distribution of retirement ages for 2004. The ‘peak period’ for retirement, looking at men and women together, is between 59 and 66 years. Figure 7 – Economic activity rates of men and women aged 50–75. Figure 8 – Estimated distribution of retirement ages for 2004. The level of the state pension in the UK is one of the lowest in MEDCs. This has a significant impact on the incomes of elderly people (Figure 9). Within Britain, pensioner incomes vary considerably by ethnic group, with White Britons receiving, on average, £265 per week, and Asian and Black Britons receiving, on average, £200 per week. Figure 9 – Median income of people aged 65+ as a percentage of median income of people aged less than 65 (2001). The ‘grey pound’ and the ‘grey vote’ As a population ages the total purchasing power of the older section of a population increases. This is clearly beneficial to companies that specialise in providing goods and services to older people. For example: In the tourist industry, cruising is a very popular type of holiday with the older age group. Some companies, such as Saga, provide a wide range of services for older people, in this case the over-50s. The housing market is adjusting to population ageing with more housing units being built specifically for the elderly. Political parties are also only too aware of the increasing voting power of the older age group. As aged dependency rises the grey vote will increase further. An alternative view Phil Mullan, in his book The Imaginary Time Bomb: Why an Ageing Population is not a Social Problem, argues that the demographic pessimists ignore the fact that ageing has been a feature of MEDCs since the late nineteenth century and countries have not had a problem coping with this process in the past. The points he makes include the following: The so-called pension crisis is not just due to demographics but also to short-sighted policies by government and private companies. He cites the taxing of pension funds since 1997 and companies’ contribution holidays and/or using the funds to finance redundancies under the guise of early retirement as examples. The calculations of the ‘pension burden’ are based on the changing support ratio. The support ratio ignores the fact that a considerable number of people of ‘working age’ do not work. This makes a great difference to what is termed the real, or economic, support ratio, which compares ‘active workers’ and non-workers, as non-workers of every age require the economic support of those who are working. Thus, the argument here is that employment rates tend to be more influential on the economic support ratio than the pace of ageing. The preoccupation with the support ratio ignores rising productivity which has been so important to improving living standards in the past. Older people are healthier than before and may not cost more in terms of health care just because they are living longer. Pensioners also pay income tax and most of the other taxes that the working population pay such as VAT and council tax. With demographic ageing there will be fewer children to educate and presumably fewer nonemployed on benefits if there is a shortage of workers. So, public spending in both of these areas should decrease allowing resources to be switched to the elderly. Mullan claims that ‘the real problem in the “pensions crisis” is not demographics, but our meanspirited attitude towards the elderly’. Conclusion For much of the post-1950 period the main demographic problem has been generally perceived as the ‘population explosion’, a result of very high fertility in LEDCs. However, greater concern is now being expressed about demographic ageing in many countries where difficult decisions about the reallocation of resources are having to be made.