Carbonbusting: appliances

Low Carbon Living Programme

Instant expert: stuff

The everyday things that we buy all contribute to our carbon footprint. This session looks at the impact of various stages along a product’s lifecycle, as well as raising the question – did we really need it in the first place?

KEY MESSAGES

Just like people, the things we own have their own carbon footprint. This is calculated by looking at eac h of the stages of a product’s lifecycle, namely:

Extraction – acquiring the raw materials.

Production – making the item.

Distribution – from factory to store to the consumer.

Consumer use – how we use the product.

End of life – what we do with things we no longer want.

Energy savings can be made at each stage, reducing its carbon footprint.

Ways we can reduce the carbon footprint of our consumption include:

Choosing greener products – ones where the manufacturer has actively reduced the impact of the extraction, production and distribution, and which will have the least impact during use and disposal.

Being responsible about the way we use the items we own.

Doing more to reuse and recycle.

However, the most effective way we can reduce the carbon footprint of our consumption is simply to reduce the amount we consume.

The carbon footprint of a product is just one measure of the impact it has on the planet. We also need to consider other environmental and social impacts our consumption choices may have.

INSTANT EXPERT CRIB NOTES

Indirect carbon footprint

Our carbon footprint relating to our consumption of goods and services is often referred to as our ‘indirect’ carbon footprint, as we aren’t directly responsible for the creation of the greenhouse gases relating to these products. However, as the end user, and the people creating the demand for these goods, we cannot duck our responsibility for these impacts.

FACT BOX

The gross disposable household income for the UK is

£14,872 a head, or £35,692 for the average household 1 – that’s the money we have to spend after taxes and pension contributions.

The annual consumption of goods and services by the average person results in around two tonnes of CO

2 e emissions.

2

The average household generates over one tonne of waste each year.

3

33% of products thrown away in the UK are still working.

4

99% of the stuff bought in North

America is thrown away within six months of purchase.

5

The carbon footprint of a plastic bag makes up one-thousandth of the carbon footprint of the food it contains.

6

Compiled Spring 2011

1 Source: Office of National Statistics Press Release, 31 March 2010: Variations in household income per head in UK regions.

2 Quicksilver calculator methodology. NB excludes food-related emissions.

3 WRAP http://www.wrap.org.uk/downloads/Environmental_benefits_of_recycling_2010_update.9c655a62.8816.pdf

4 WRAP, 2009, Meeting the UK Climate change challenge: The contribution of resource efficiency .

5 Anne Leonard, The Story of Stuff

6 Mike Berners-Lee How Bad are Bananas?

www.lowcarbonliving.org.uk

The carbon footprint of the things we use

The lifecycle of the stuff we buy can be thought of as passing through a number of phases, namely the extraction of the raw materials, production, distribution, consumption, and ultimately the item’s disposal.

Lifecycle impact analysis, also known as ‘cradle to grave’ analysis, looks at the greenhouse emissions of each of these stages in turn to calculate the overall carbon footprint of the product. As with food, there are so many variables involved that even two seemingly-identical products can have very different carbon footprints.

Nevertheless, by looking at the each of the stages, it’s possible to identify choices we have to enable us to choose greener products and minimise their impact. Take, for example, the lifecycle of a t-shirt.

Lifecycle analysis of a t-shirt

Source: Sustainable Clothing Road Map, Progress Report 2011, DEFRA Crown Copyright 2011 7

At each stage, different choices made by the manufacturer and consumer can have a major impact on the carbon footprint of an item.

Production versus consumption impacts

The elements that make up the carbon footprint of the things we buy can be split into those that happen during the production and sale of the item, and those that take place once the consumer has the item. Both elements have an important role to play in reducing the overall impact of a product.

Production

Production covers the sourcing of materials, manufacturing processes, waste management and distribution choices of the manufacturers, as well as retail and marketing activities. The choices made by retailers, manufacturers and their suppliers can have a significant impact on the energy that goes into making a product

(its ‘embodied energy’) and its environmental impact.

For example, the Continental Clothing Company looked at the whole process of making their t-shirts: from the cotton field, through processing, manufacturing, transport, up to the point of our distribution warehouses. By identifying gre enhouse gas ‘hotspots’ they then reduced the emissions of producing their t-shirts to just 0.7kg – ten times less than the average t-shirt.

8

Another example is washing-liquid manufacturers who, by making their products more concentrated, have reduced packaging and transport emissions.

Sustainability

Sustainability is about our ability to meet the

7 needs of the present without compromising

8 the ability of future generations to meet their

2 own needs.

9 measure of the many ways the production, use and disposal of things impacts on our planet and the people we share it with.

Although the production of items is out of the direct control of consumers, we can influence this process by lobbying companies to improve their practices, and shunning companies with poor environmental practices in favour of those who have reduced the environmental impact of their products. Very few products actually state their carbon footprint on the pack, so, as with food, we need to make choices based on our assumptions about the raw materials and production methods used to make the product, and distribution systems used to get it to us.

Consumption

How we make use of the products we purchase, and how we eventually dispose of them, also has a major impact on their overall carbon footprint. For example, how frequently and at what temperature we wash our clothes, and whether we tumble-dry them, will result in very different carbon emissions. Some studies suggest that emissions from these can account for up to 75% of the total carbon footprint of a t-shirt.

11

The disposable versus washable nappy debate is an example of how assumptions in user behaviour can alter the environmental impact of different options. If the carbon footprint of a disposal nappy is compared to that of a washable nappy which is washed at 90

C and tumble-dried, the disposable has a lower carbon footprint.

However, change the washing temperature to 60

C, line dry, and ensure the washable nappy is passed on to a second child, and the outcome is reversed.

12

The decisions we make about how to dispose of a product at the end of its life will also impact on its carbon footprint. In the above example, passing on washable nappies once your child no longer needs them makes all the difference to their environmental impact compared to disposables.

To some extent, the cho ices we have in using and disposing of items will be restricted by the manufacturer’s design of the product and choices they made over materials used in their production.

A note about national carbon footprints

Every year the UK government submits figures about the UK’s overall greenhouse gas emissions, using reporting guidelines set out in the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. These look at all the greenhouse gas emissions taking place within that country’s territory. A criticism of these figures is that they don’t take into account imports or exports, or international transport emissions.

The Norwegian University of Science and Technology reformulates these national footprints, based on where the products were consumed rather than manufactured, and to also include international transport emissions.

Its ‘Footprints of Nations’ can be found at http://carbonfootprintofnations.com.

Its work led it to the following conclusions:

Emissions shift from food to manufactured products and mobility as household income goes up.

There is a clear relationship between total consumer expenditure and carbon footprint in different categories. There is no flattening out – no indication that the carbon footprint stabilises at some point. It concludes this means we cannot expect that emissions are reduced as a part of normal development.

One Planet Living

‘One Planet Living’ is a global initiative that looks at sustainability in a way that helps people live and work wit hin a fair share of our planet’s resources. It estimates that if everyone on the planet was to live like an average European, we would need three planets to live on. The website, www.oneplanetliving.org, sets out ten principles of sustainability.

Strategies for reducing our consumption-based greenhouse gas emissions

There are a wide range of strategies we can use to reduce the carbon footprint of the stuff we consume.

Although this section focuses on reducing greenhouse gas emissions, many of the strategies suggested also have broader implications in terms of sustainability – reducing our consumption of natural resources, pollution and waste generation.

9 Brundtland Commission Definition 1987

10 Riverford Organics http://www.riverfordenvironment.co.uk/Packaging.aspx

11 For example, Navarro F.J., University of Queensland 2008

12 Mike Berners-Lee How bad are bananas?

3 www.lowcarbonliving.org.uk

Reduce

By far the simplest way to reduce the carbon footprint of the things we buy is to buy fewer things! Strategies include:

Avoiding disposable or single-use items – from bags to bottled water.

Sharing – most homes have a lawn mower, yet we only use them for a few minutes every month. Sharing key items with friends and neighbours not only reduces the amount of materials used to keep us in lawn mowers and the like, but also saves valuable cupboard space. Online sharing clubs, such as www.ecomodo.com, can be used to advertise and share items within your community. Sharing books with friends – or better still, by using your local library – is another example.

Shopping has become a pastime for many, and purchasing new things seen as a way of treating ourselves.

There are lots of other ways of rewarding ourselves – making the time to see friends, for example – which are less carbon intensive, and less impactful on our bank balances.

We can also reduce the carbon footprint of the things we buy through our purchasing choices. For example:

Choose the most environmentally-friendly option. Some companies have worked hard to reduce the carbon footprint of their products by improving manufacturing techniques, increasing the use of recycled materials in their products, reducing packaging, and making what packaging is used recyclable.

Avoid purchasing items which are made out of carbon-intensive materials. Chris Goodall singles out metalbased electronics, textiles (especially wool and cotton), and paper-based products in his book How to Live a Low-Carbon Life .

Buy a smaller appliance – thereby reducing the embodied energy used to manufacture it – and in all likelihood you’ll also reduce its running costs.

Choose items where much of the cost is towards the time of skilled craftspeople rather than materials.

Buy items made of recycled materials – not only are you reducing the use of raw materials, but also creating a market to encourage further recycling.

Choose services over products – again, the more of what you pay is invested in people rather than materials, the less direct carbon impact your money may have.

Finally, much of the stuff that we accumulate isn’t things that we buy, but things that are given to us. Join the mailing preference service (www.mpsonline.org.uk) to reduce junk mail, and why not request an

‘experiences’, such as a trip to theatre, rather than ‘things’ for your birthday present.

Reuse

As a significant chunk of the carbon footprint of an item results from the beginning and end of its life, the more we can do to get the most out of that ‘energy investment’ in an item the better. There are two key areas to be aware of when it comes to reuse:

‘Planned obsolescence’ – single-use items are obvious examples of planned obsolescence – from paper cups to disposable BBQs – but it is often a feature of far more expensive items too. When buying new items, check how long manufacturers intend to supply spare parts and provide service cover. Technology is especially prone to issues of obsolescence, as any owner of a video player can tell you.

‘Perceived obsolescence’ – Fashion is a classic example of this. Constantly-shifting hem lines and heel heights serve to keep us purchasing the latest fashions rather than risk being seen in la st year’s trends.

Buy good quality items that are made to last.

Repair rather than replace when possible.

Pass on items you no longer need so someone else gets to use them – to friends, neighbours, charity shops, via Freecycle, or sell them on Gumtree or eBay.

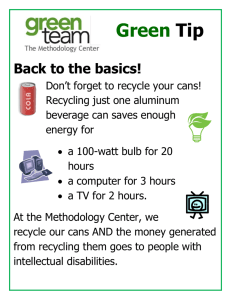

Recycle

4 www.lowcarbonliving.org.uk

The packaging and materials that reach us, the end consumer, make up just a fraction of the total materials associated with the production, transportation and packaging to needed make the item in the first place – just one 70 th , according to Annie Leonard in the film The Story of Stuff . It also takes yet more energy to recycle products, so recycling should neve r been seen as the ‘solution’, but rather as a responsible way of minimising the impact of the purchases we do make.

Recycling our waste is still an important activity. As well as clogging up landfills, simply chucking away our household waste has two significant environmental implications:

- Firstly, ‘locking up’ materials. Much energy has already been expended to extract and process the raw materials that make up products and their packaging. Chucking them into landfill means these are no longer available to us.

- Secondly, rotting packaging and other organic materials generate greenhouse gases such as methane.

Methane is 23 times more potent a greenhouse gas than CO

2.

Greater understanding as to which materials can be recycled is a frequent request from householders. The

Recycle Now website, www.recyclenow.com, has everything you could ever want to know about recycling including:

A comprehensive guide as to which materials can be recycled – from spectacles to small electrical items.

A widget that tells you what is collected in your kerbside collection, based on your postcode.

Background information about the recycling process for key types of waste.

An explanation of recycling symbols.

Home composting tips.

Another excellent source of composting tips is available at the Gardening Organics website: http://www.gardenorganic.org.uk/composting/index.php

Its ‘Master Composter’ scheme trains people all over the country to support their neighbours in their composting ventures. Check out http://www.homecomposting.org.uk/ to sign up for training. There may already be Master Composters in your area. For example, in Oxfordshire you can ‘book’ a Master Composter via the

Oxfordshire Waste Partnership website.

Stuff and happiness

Annie Leonard, creator of The Story of Stuff says that, of course when we do shop we should shop responsibly, but the solutions that we need are not for sale at the store. In other words, w e can’t buy our way out of the problem – we need to just buy less. She concludes: “saddest of all we are trashing the planet, trashing our relationships and not even having fun.

”

“Gross National Product measures everything, except that which makes life worthwhile.

”

Robert F. Kennedy

The New Economics Foundation produces an annual index of well-being, and has concluded that since 1970 the UK’s GDP has doubled, but people’s satisfaction with life has hardly changed.

13

You can measure your own well-being by taking a survey on its website: http://www.nationalaccountsofwellbeing.org/engage/survey.html

So, it appears that although many people measure their success in terms of their accumulation of stuff, it doesn’t bring us happiness. Perhaps we would be happier in a society which valued qualities such as stewardship, resourcefulness and thrift above the brand of jeans we wear.

Key definitions

Lifecycle analysis

Lifecycle analysis is a comprehensive ecological assessment that identifies the energy, material, and waste flows of a product, and their impact on the environment. This cradle to grave evaluation begins with the design

13

New Economics Foundation http://www.neweconomics.org/programmes/well-being.

5 www.lowcarbonliving.org.uk

of the product, and progresses through the extraction and use of its raw materials, manufacturing or processing with associated waste stream, storage, distribution, use, and its disposal or recycling. The objective is to identify changes, at every stage of the lifecycle, that can lead to environmental benefits and overall cost savings. It is also called life cycle impact assessment 14 or cradle to grave analysis.

Well-being

Personal wellbeing describes people’s experiences of their positive and negative emotions, satisfaction, vitality, resilience, self-esteem, and sense of purpose and meaning. Social well-being is made up of two main components: supportive relationships, and a feeling of trust and belonging. Together they form a picture of what we all really want: a fulfilling and happy life.

15

FURTHER INFORMATION

Reduce Reuse Recycle – An easy household guide by Nicky Scott, Green Books Guides

How Bad are Bananas?

Mike Berners-Lee, Profile Books

How to Live a Low-Carbon Life Chris Goodall

WRAP (Waste & Resources Action Programme) works in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland to help businesses and individuals reap the benefits of reducing waste; develop sustainable products; and use resources in an efficient way. Its website is a mine of waste-related information: www.wrap.org.uk/ www.recyclenow.com has detailed information about recycling services available in your area, as well as information about how a wide range of household waste is recycled.

The Story of Stuff website has a range of informative and inspirational short films which you can view online. As well as the eponymous The Story of Stuff , there are films looking at a range of other products such as electronics and bottled water: www.storyofstuff.com

The New Economics Foundation is an independent think-and-do tank that inspires and demonstrates real economic well-being. It publishes the Happy Planet Index and National Accounts of Well-being. www.neweconomics.org

This work is part of the Low Carbon Living Toolkit and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-

NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. If you have any questions or tips to suggest please email them to us at lowcarbon@hotmail.co.uk v 1.3 21/09/09

Whilst we have made every attempt to ensure the accuracy of this leaflet, this information should not be relied upon as a substitute for formal advice. LCWO will not be responsible for any loss, however arising, from the use of, or reliance on this information. Low Carbon West Oxford is a registered charity 1135225.

APPENDIX A: KEY TO RECYCLING SYMBOLS

Reproduced from the Recycle Now website: www.recyclenow.com

Nine out of ten households now have a kerbside collection, so check the postcode locator to find out what you can recycle in your area. Remember, 73% of packaging can currently be recycled in England but we only recycle 33%, so there’s room for improvement!

Numerous labels appear on packaging to advise consumers and promote environmental claims. To ensure these claims are accurate, a set of international standards has been developed, known as the Green Claims

Code, and is issued by the British Standards Institute. To help you understand all the symbols you might see, take a glance at the guide below...

The Recycle Mark

14

Business Dictionary.com

15

New Economics Foundation: www.neweconomics.org/projects/national-accounts-well-being [viewed 21 September 2011]

6 www.lowcarbonliving.org.uk

The Recycle Mark is a call for action. Please try and recycle whenever possible. If you are unsure if the item is collected locally, check the postcode locator.

The new packaging symbols

New packaging symbols are now starting to appear on some packaging. They help to identify how different parts of packaging can be recycled.

‘Widely recycled’: 65% of people have access to recycling facilities for these items.

‘Check locally’:15-65% of people have access to recycling facilities for these items.

‘Not recycled’: less than 15% of people have access to recycling facilities for these items.

These symbols are a guide to how widely different packaging items are recycled; however, you should always follow the advice of your local authority. Check the postcode locator and see what you can recycle in your area.

The Green Dot – the Green Dot does NOT necessarily mean that the packaging can be recycled. It is a symbol used on packaging in many European countries, and signifies that the producer has made a contribution towards the recycling of packaging.

Plastics – identifies the type of plastic: PET and HDPE bottles are recycled by the majority of local authorities.

Glass – please dispose of glass bottles and jars in a bottle bank (but remember to separate colours) or use your glass kerbside collection if you have one.

Recyclable aluminium

Can be placed in an aluminium recycling facility.

Recyclable steel

Can be placed in a steel recycling facility.

Mobius loop

Indicates that an object is capable of being recycled – not that the object has been recycled.

Mobius loop with percentage

Shows the percentage of recycled material contained in the product.

Paper – to be given the National Association of Paper Merchants mark, paper or board must be made from a minimum of 75% genuine waste paper and/or board fibre, no part of which should contain mill-produced waste fibre.

Wood.

The Forest Stewardship Council logo identifies products which contain wood from well managed forests, independently certified in accordance with the rules of the Forest Stewardship Council.

Tidyman

Dispose of this carefully and thoughtfully. Do not litter. This doesn’t relate to recycling, but is a reminder to be a good citizen, disposing of the item in the most appropriate manner.

The American Society of Plastics Industry developed a standard marking code to help consumers identify and sort the main types of plastic. These are:

Polyethylene terephthalate – fizzy drink bottles and oven-ready meal trays.

7 www.lowcarbonliving.org.uk

High-density polyethylene – bottles for milk and washing-up liquids.

Polyvinyl chloride – food trays, cling film, bottles for squash, mineral water and shampoo.

Low density polyethylene – carrier bags and bin liners.

Polypropylene – margarine tubs, microwaveable meal trays.

Polystyrene – yoghurt pots, foam meat or fish trays, hamburger boxes and egg cartons, vending cups, plastic cutlery, protective packaging for electronic goods and toys.

Any other plastics that do not fall into any of the above categories. An example is melamine, which is often used in plastic plates and cups.

Degradable plastics – these are oil-based, and either eventually break down or disperse into smaller fragments. These may then potentially biodegrade or break down further to reduce the material to water, CO

2

, biomass (plant matter) and trace elements.

Biodegradable plastics – these should break down cleanly, in a defined time period, to form simple molecules found in the environment such as CO

2 and water. The predominant mechanism in the decomposition of biodegradable plastics is the action of micro-organisms which produces CO

2

, methane, water, inorganic compounds, or biomass.

Compostable plastics – these are a subset of biodegradable plastics which must demonstrate that they biodegrade and disintegrate completely in a compost bin or system during the 3-4 months composting process.

It refers to ‘industrial composting’ where the compost reaches higher temperatures than home composting.

Disposal of degradable and biodegradable plastics – these plastics will not degrade effectively in a landfill site and could potentially hinder the quality of recycled plastic if they enter a conventional plastics recycling system.

For further information about recycling, including postcode-based information about what recycling services are available to you, go to the Recycle Website: www.recyclenow.com

8 www.lowcarbonliving.org.uk