Paper

advertisement

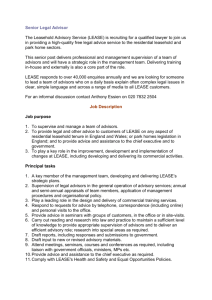

The Valuation and Disclosure Implications of FIN 46 for Synthetic Leases: Off-Balance Sheet Financing of Real Property Carolyn M. Callahan Doris M. Cook Professor University of Arkansas-Fayetteville Angela Wheeler Spencer Assistant Professor Oklahoma State University 10/12/06, Draft Please do not quote or distribute without the express permission of the authors. * Corresponding Author Business Building, 454 1 University of Arkansas Fayetteville, AR 72701 Phone: (479) 575-6126 Fax: (479) 575-2863 CCallahan@walton.uark.edu We thank E. Ann Gabriel, Maureen Butler, Kim Church, and Rajesh Narayanan for their insightful comments on earlier drafts of this paper. We are grateful for the helpful suggestions provided by workshop participants at Oklahoma State University, University of Memphis, and University of Oklahoma. 1 Abstract This study examines the valuation and disclosure impact of Financial Interpretation Number (FIN) 46 on firms that disclosed involvement as a synthetic lessee with a variable interest entity (VIE) post-FIN 46. Synthetic leasing firms were chosen for this particular study because contrasting the disclosures required for these leases as off-balance sheet operating leases before FIN 46 with the change to a capitalized presentation of these same leases after adoption of FIN 46 presents an ideal opportunity to examine differences between recognition and disclosure. We specifically examine whether the differential disclosure and recognition accounting imposed by FIN 46 to improve financial statement transparency impacts market valuation. Results of this study indicate that while disclosed future minimum lease payments are significantly valued by the market pre- and post-FIN 46, financial statement recognized lease liabilities are valued with substantially more weight following FIN 46. Further, while the new maximum risk disclosures required under FIN 46 are valued by the market, they do not incrementally add valuation information beyond the already required lease disclosures. 2 I: Introduction This study examines the market valuation and disclosure impact of Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) issued Interpretation No. 46, Consolidation of Variable Interest Entities on firms that disclosed involvement as a synthetic lessee with a variable interest entity (VIE) post-FIN 46. The synthetic lease was originally designed as a hybrid financing structure that allowed a company to have many of the benefits of asset ownership, including capital lease treatment for tax purposes, while treating lease payments as operating expenses on the firm’s income statement. Proponents of these transactions argued that the synthetic lease was necessary to provide economic benefits to the firm and its shareholders. Critics argued that these transactions (similar to other off-balance sheet liabilities) were severely lacking in financial statement transparency, a matter of concern to accounting regulators in the wake of recent corporate financial reporting scandals. The FASB issued Financial Interpretation No. 46 (FIN 46), Consolidation of Variable Interest Entities, in January 2003 and subsequently revised it in December 2003. The new guidance included in the Interpretation is specifically directed at the use of off-balance-sheet entities such as synthetic leases. Synthetic leasing firms were chosen for this particular study because contrasting the disclosures required for these structures as off-balance sheet operating leases before FIN 46 with the change to a capitalized presentation of these same leases after adoption of FIN 46 presents an ideal opportunity to examine alternative recognition versus disclosure effects. We specifically examine whether the differential disclosure and recognition accounting imposed by FIN 46 to improve financial statement transparency impacts market valuation and consider the specific financing action taken by the firm in response to FIN46. 3 While existing work (Imhoff, Lipe and Wright 1993; Ely 1995; Bauman 2003) supports the idea that disclosed items are valued by the market, evidence also indicates that recognized items are valued with more weight than are disclosed items (Davis-Friday et al. 1999; Ahmed, Kilic, and Lobo 2006). Using market valuation analysis, this study examines this issue further by evaluating how the market values disclosed lease obligations (both before and after FIN 46) and recognized lease liabilities (post-FIN 46). Of additional interest are the expanded VIE disclosures required under FIN 46, in particular, the “maximum risk” disclosures required for firms with significant VIE relationships that are not consolidated. While existing evidence shows that disclosures providing supplemental information to recognized amounts are significantly considered by the market (Barth, Beaver, and Landsman 1996; Graham, Lefanowicz, and Petroni 2003) and experimental evidence suggests that detailed disclosures about loss outcomes influence financial statement users (Koonce, McAnally, and Mercer 2005), valuation analysis of this issue provides evidence as to whether additional disclosures of this nature augment those disclosures already required. Finally, considering that a substantial body of evidence supports the idea that increased disclosure is viewed positively by the market, firm reaction to FIN 46 is also considered. Even though FIN 46 mandates accounting changes, firms still could have chosen to restructure or unwind their VIEs to avoid having vehicles that fell under the purview of FIN 46. However, because prior research (Botosan 1997; Botosan and Plumlee 2002) has established that the market responds more favorably to greater disclosure, a firm’s willingness to comply with FIN 46 (rather than divest or restructure the VIE) could lead to a positive impact on market value. Results of this study indicate that while disclosed future minimum lease payments are significantly valued by the market pre- and post-FIN 46, lease liabilities recognized in the 4 financial statements are valued with substantially more weight following FIN 46. Further, while the new maximum risk disclosures required under FIN 46 are valued by the market, they do not incrementally add valuation information beyond the already required lease disclosures. Further, the firm’s choice of whether to follow the provisions of FIN 46 or to restructure or divest the lease arrangement does not appear to be significantly valued by the market. The evidence of significant differences between recognition and disclosure of recognized lease liabilities post-FIN 46 has the potential to contribute to the ongoing lease accounting debate. For instance, the Securities and Exchange Commission, in a 2005 report on off-balance-sheet activity commissioned by Congress as part of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, argued that general lease accounting standards should be rewritten, estimating that they allow publicly traded companies to keep $1.25 trillion (undiscounted) in future cash obligations off their balance sheets. The remainder of this paper proceeds as follows: Section II: Institutional Background Section III: Prior Literature; Section IV: Hypotheses Development; Section V: Sample Selection and Statistical Analysis VI: Results and Conclusions. II: Institutional Background Financial Interpretation Number (FIN) 46 Variable interest entities, a term introduced by FIN 46 and defined by that standard, are those entities that have one or more of the following characteristics1: 1. The equity investment at risk is not sufficient to permit the entity to finance its activities without additional subordinated financial support provided by any parties, including the equity holders. 2. The equity investors lack one or more of the following essential characteristics of a controlling financial interest: 1 All excerpts and quotes attributed to“FIN 46” in this chapter are taken from the revised version, FIN 46(R). 5 a. The direct or indirect ability through voting rights or similar rights to make decisions about the entity’s activities that have a significant effect on the success of the entity. b. The obligation to absorb the expected losses of the entity. c. The right to receive the expected residual returns of the entity. 3. (i) The voting rights of some investors are not proportional to their obligations to absorb the expected losses of the entity, their rights to receive the expected residual returns of the entity, or both and (ii) substantially all of the entity’s activities either involve or are conducted on behalf of an investor that has disproportionately few voting rights. VIEs, part of the broader category of special purpose entities (SPEs), have long been used to carry out specific activities and transactions, such as leasing equipment back to the parent company, securitization of accounts receivable, and research and development. Although these vehicles were used beginning in the 1970s to handle a wide variety of transactions, popularity of at least some of these arrangements seems to have increased in recent years. For example, a July 2004 article reported that in 1999, securitization and synthetic lease SPEs constituted a total of $50,660 million; by 2001, this total had increased to $229.774 million (Sorrosh and Ciesielski 2004). But, with only minimal financial statement disclosure, SPEs weren’t widely discussed for most of their history. With FIN 46, the FASB altered the requirements for consolidation of VIEs,2 requiring enhanced reporting in the financial statements and notes of the parent firms. FIN 46 was enacted with the stated goals of improving financial reporting by (a) generating greater consistency across firms with regard to consolidation policies and (b) enabling financial statement users to more effectively measure each entity’s risk through increased note disclosure (7). As described in ARB 51 (and as cited in FIN 46), consolidated statements are “usually necessary for a fair presentation when one of the companies in the group directly or indirectly 2 Other classes of SPEs, for example qualifying SPEs (QSPEs) and SPEs of governmental and not-for-organizations, are not impacted by FIN 46. QSPEs are allowed to remain off-balance sheet via the provisions of SFAS 140, Accounting for Transfers and Servicing of Financial Assets and Extinguisment of Liabilities. 6 has a controlling financial interest in the other companies (¶1).” Under ARB 51, “the usual condition for a controlling financial interest is ownership of a majority voting interest . . . (¶2).” However, as VIEs have non-traditional structures, ARB 51 was generally not sufficient to force consolidation by the appropriate parties because, as FIN 46 notes, the “controlling financial interest may be achieved through arrangements that do not involve voting interest (¶1).” To rectify this situation, FIN 46 mandates a new process for determining whether or not a variable interest entity should be consolidated. At issue first is whether the firm has a variable interest in a variable interest entity (see above for a description of the term “variable interest entity”). Under FIN 46, “variable interests” are “contractual, ownership, or other pecuniary interest in an entity that change with changes in the fair value of the entity’s net assets exclusive of variable interests (emphasis added) (¶2). Once it has been established that the firm holds a variable interest in a variable interest entity, at issue next is whether the firm is the “primary beneficiary.” FIN 46 defines the primary beneficiary as the firm that has the variable interest which will absorb a majority of the entity’s expected losses, receive a majority of the entity’s expected residual returns, or both (¶14).” If the firm is found to be the primary beneficiary, the VIE is consolidated, following the same methodology utilized under ARB 51. By requiring consistent consolidation (regardless of the particulars of each contract), based on the risk and rewards underlying each leasing arrangement, FIN 46 quite closely implements the recommendations made by the AAA Financial Accounting Standards Committee in 2001. In cases where a firm holds a significant interest in a variable interest entity but the requirements for consolidation (under FIN 46) are not met, the firm must still make certain disclosures. Specifically, the firm must disclose the nature of its involvement with the VIE, the 7 scope of that involvement, and the firm’s maximum exposure to loss due to its involvement with the VIE. This last disclosure is of particular interest because it requires the firm to quantitatively disclose its at risk position in the VIE. Maximum risk disclosures made following FIN 46 included a wide variety from items. Some, such as minimum lease payments and guaranteed residual values related to leases had previously been disclosed in a standard format (due to the fact that synthetic leases were treated as operating leases for financial reporting purposes prior to FIN 46). Others, such as loan guarantees for a third party, did not necessarily receive standard or complete disclosure prior to FIN 46. Conceivably, such disclosures should have better informed the market (at the very least drawing more attention to previously disclosed amounts) but what is still unknown (and what this study in part seeks to answer) is whether such disclosures incrementally impacted firm valuation by the market. Synthetic Leases Arising after the collapse of the traditional real estate financing market in the late 1980s and early 1990s, synthetic leases were initially used by only a limited number of firms seeking to fill a financing void. However, fueled by the technology boom of the 1990s, synthetic leasing became a much more commonplace financing vehicle, used by rapidly growing firms and others in need of low cost capital financing (Ratner 1996). These structures promised numerous benefits, from direct effects such as favorable tax treatment, to indirect effects such as improved market valuation due to the off-balance sheet treatment of the leases. However, in order to achieve the touted benefits, exact structuring of the synthetic lease was required. In general terms, a synthetic lease was one that met FASB guidelines to qualify as an operating lease, but also met IRS guidelines to qualify as a capital lease (Dorsey 2000). In a synthetic lease, the leasing firm created a special purpose entity (SPE) structured solely to obtain 8 a particular asset and secure sufficient financing for the asset’s purchase. Typically, this financing was obtained through a 3% equity investment (from a source external to the lessee) and a 97% debt interest (Little 2002) (See Figure 1). By securing a 3% equity interest from an outside party, under EITF 90-15, the equity interest was deemed to be “substantive” and the equity holder “at risk,” thus preventing the lessee from consolidating the SPE (Ratner 1996). Further, the leasing arrangement was structured such that all four capitalization criteria of SFAS No. 133 were not met, thus qualifying the lease for operating, rather than capital, lease treatment (Evans 1996). Such a structure, however, was not without risks as the lessee firm typically guaranteed the debt used to finance the asset purchase (Muto and Veverka 1997). The most obvious effect from such a structure was that the lease remained largely out of the financial statements of the lessee. By qualifying as an operating, rather than capital, lease SFAS No. 13 only required that the lease payments be expensed on the income statement and the future minimum lease payments disclosed in the notes to the financial statements. By achieving off-balance sheet treatment for the lease, lessee firms hoped to obtain several benefits, including improved reported earnings (due to the avoidance of the reporting of depreciation expense), improved financial ratios (due to enhanced earnings and lower asset and liability totals on the balance sheet) and improved market valuation (due to improved earnings and balance sheet position) (Muto and Veverka 1997; Ratner 1996). The second major set of benefits from this lease structure involved the favorable tax treatment afforded the lease. By virtue of the fact that the lessee bore the long-term burdens and benefits of property ownership with relation to the leased asset, the IRS criteria for a “conditional sale” were met, allowing the lessee to deduct both depreciation and interest associated with the (1) Transfer of ownership, (2) bargain purchase option, (3) lease term is greater than or equal to 75% of the asset’s economic life, or (4) the present value of the minimum lease payments are greater than or equal to 90% of the fair value of the asset. 3 9 lease on the corporate tax return (Muto and Veverka 1997). Thus, by utilizing a synthetic lease, the lessee firm was able to have the best of both worlds: minimize the lease’s presence in the financial statements, but maximize it on the tax return. Further expected benefits of the synthetic lease structure included: Enhanced cash flow (when compared to traditional financing). Synthetic lease payments were typically structured to equal debt service (generally interest only) and a minimum return to the equity holders. Further, synthetic leases generally provided 100% financing for a given project (Little 2002). Lower financing costs. In most cases, the SPE’s loan was “double-backed” by both the collateralized asset and the lessee’s credit. Additionally, SPEs were usually considered “bankruptcy remote.”4 Such features often allowed the lessee to save between 2 ½ to 3% interest points when compared to traditional financing mechanisms (Muto and Veverka 1997; AAA Financial Accounting Standards Committee 2003). Retention of property appreciation. Lessees were generally able to retain any property appreciation due to the fact that most of these lease agreements contained a fixed purchase price clause (Little 2002). Lowered transaction costs. Lowered costs associated with the property itself often resulted due to the transaction economic benefits that were available due to the “all in” nature of the SPE structure (Evans 1996). Under FIN 46, the financial statement treatment of synthetic leases is only impacted if the leases are held by a special purpose entity (SPE) that has been determined to be a variable interest 4 The assets of the SPE cannot be drawn upon to satisfy bankruptcy claims against the sponsoring firm. 10 entity (VIE) in which the controlling interest is held by the lessee. In that case, the lessee must consolidate the VIE for financial reporting purposes (Danvers, Reinstein, and Jones 2003). As noted above, synthetic lease structures typically involved three parties: the tenant, the landlord, and the lender. The landlord (nominal owner), in most cases, purchased the property in question strictly based on the tenant’s commitment to lease the property and the tenant’s corporate credit (Dorsey 2000). Such arrangements, with benefits accrued by a party other than the technical owner (lessor SPE) of the property, clearly fall under the scope of FIN 46. III: Prior Literature The FASB has always maintained that disclosure and recognition serve different purposes. As outlined in SFAC No. 5, and highlighted by Johnson (1992) “although financial statements have essentially the same objectives as financial reporting, some useful information is better provided by financial statements and some is better provided, or can only be provided, by notes to the financial statements or by supplementary information or other means of financial reporting (¶7) and “generally, the most useful (emphasis added) information about assets, liabilities, revenues, expenses, and other items of financial statements and their measures (that with the best combination of relevance and reliability) should be recognized in the financial statements (¶ 9).” Therefore, if the market considers the FASB’s Conceptual Framework, it should perhaps not value disclosed items in the same manner as those that are recognized. Further, given the volume of disclosures that are currently required by GAAP, some wonder if there might not be a problem with “disclosure overload (Johnson 1992).” That is, does too much required information in annual reports prevent some information from receiving proper consideration? 11 Such issues lead to the two questions at the heart of this study. First, does the market value disclosed and recognized items differently? Second, did the recognition and disclosure provisions of FIN 46 impact market valuation? Such analyses draw upon a variety of literatures, including that which examines the incremental valuation impact of disclosures and differences between disclosure and recognition. Analysis of these works seems to indicate that while the market does indeed value disclosed items, they receive less emphasis than items recognized in the financial statements. Although it can be gathered from Statement of Financial Accounting Concepts No. 5 that disclosure and recognition are not substitutes, there is evidence that the market does value items that are disclosed but not recognized. Existing work, consistent with the efficient market hypothesis, provides support for the idea that the market does price disclosures. Two of these studies, Imhoff, Lipe and Wright (1993) and Ely (1995), find that investors constructively capitalize operating lease disclosures when assessing equity risk. That is, the market is not deceived by the fact that operating leases are disclosed in the notes rather than recognized in the financial statements. Likewise, in a study examining the effects of off-balance sheet activities that are “concealed” by the equity method of accounting, Bauman (2003) finds that the market significantly considers footnote disclosures to value off-balance sheet obligations “concealed” by the equity method of accounting. Considering these studies, it seems highly likely that the valuation of VIEs (for which footnote disclosure and income statement recognition was provided pre-FIN 46) would follow a similar pattern. Thus, for many VIEs, in particular those involving leases, the market was likely informed (to some degree) about these off-balance sheet activities prior to FIN 46. 12 Although disclosures are priced, a study of SFAS No. 106 (involving post-retirement benefits) found that modest (and model-sensitive) evidence does exist to indicate that the market values items on the balance sheet more strongly than those that are simply disclosed (DavisFriday, et al. 1999). Likewise, Imhoff, Lipe, and Wright (1993) found that, although operating leases are considered by the equity markets, they are only naively valued and are not considered in determining executive compensation. Further, in a study centering on derivative disclosure and recognition change surrounding SFAS No. 133, Ahmed, Kilic, and Lobo (2006) found that only recognized derivative information is significantly valued. In her Presidential Lecture at the 2005 American Accounting Association annual meeting, FASB board member Katherine Schipper suggested, consistent with the Conceptual Framework, that this difference in valuation may be due to the perception that disclosed items are less reliable (and thus should be assigned less weight) than those that are recognized. Experimental evidence supports this notion, finding in fact that the choice of whether to disclose or recognize an item may impact reliability, as auditors are more likely to allow misstatements in lease and stock compensation amounts that are disclosed rather than recognized (Libby, Nelson, and Hunton 2006). Considered together, these results seem to indicate that, although VIEs may have been considered prior to FIN 46, it is likely that they were not valued at their full weight until they were recognized. If this difference is due to perceived greater reliability associated with recognition in the financial statements (as opposed to disclosure in the footnotes), it seems reasonable to assume that a wealth effect would be experienced following the market’s consideration of firms consolidating VIEs under FIN 46. Because equity prices are established, in theory, based on the market’s expectation about the future performance of the firm and the perceived risk associated with this performance, greater reliability assigned to estimates of risk 13 should decrease the expected value of the equity interest. Further, investors purchase securities with the expectation that they are assuming a given amount of risk (which can be diversified away) in exchange for a given return. However, if it is the case that the return is in fact less than what was originally perceived (prior to the consolidation of VIEs under FIN 46), investors may divest from the security once the “real” return is more clearly revealed (i.e. post-FIN 46). Thus, a wealth effect is expected once firms consolidate VIEs following implementation of FIN 46. In a second group of studies, disclosures augmenting recognized items are examined. Of these, Barth, Beaver, and Landsman (1996) find that fair value disclosures regarding loans provided additional information which incrementally informed the market beyond the recognized book values. Similarly, Graham, Lefanowicz, and Petroni (2003) find that fair value disclosures for equity method investments have significant explanatory power. Further, experimental evidence indicates that detailed disclosures about potential loss outcomes heavily influence financial statement users (Koonce, McAnally, and Mercer, 2005). From these results, it seems likely that maximum risk disclosures, even if ancillary to already recognized or disclosed amounts, should possess significant explanatory power. In addition to evaluating how this “new” information impacted the market’s assessment of the risk associated with the firm’s financial obligations, a second issue is whether FIN 46 allowed better evaluation of the risk associated with management financing and disclosure choice. For any number of reasons (contracting, debt covenants, etc.) management of these firms established off-balance sheet arrangements that would allow them to limit the amount of disclosure provided to the market. Once FIN 46 was effective, some firms adopted its provisions, either consolidating or disclosing their VIEs, while others promptly restructured their financing arrangements to avoid consolidation or disclosure. Such actions can be interpreted to 14 signal something about the firm’s disclosure policies. Thus, for those firms that were more open with their information flow (consolidating or disclosing VIEs), a more positive/less negative reaction is expected when compared to those firms that opted to be less forthcoming (divesting VIEs) with their information flow. Such an expectation is based, in part, on evidence from Botosan (1997) and others which provides evidence that a negative relationship exists between cost of capital and disclosure level. Considering the literature that exists, the first basic question proposed is this: what is the valuation impact of FIN 46 for firms that engaged in synthetic lease operations? The second: how did the firm’s response to FIN 46 impact market valuation? The third: did maximum risk disclosures, as required by FIN 46, incrementally inform the market? The answers to these questions should be of interest to managers, who must make financing and disclosure choices and to regulators, who are interested in both the impact of such activities and the impact of new reporting requirements. IV: Hypotheses Development Based on evidence that supports the idea that disclosures, particularly those involving operating leases, are valued by the market, it seems reasonable to expect that for lessee firms of lease VIEs, the disclosures made about these leases were considered prior to FIN 46. However, based on the evidence contrasting disclosures with recognized items, it also seems highly likely that the market more strongly valued consolidated lease liabilities, post-FIN 46, than it did disclosed abbreviated lease liabilities prior to FIN 46. Thus, H1: Recognized synthetic lease liabilities are valued with greater weight than are disclosed lease liabilities. Further, based on evidence that supports the idea that the market responds more favorably to firms with more open disclosure policies, it seems that once the market becomes aware of a 15 firm’s synthetic lease activities, the market valuation may be different depending on which action the firm takes regarding its VIE. It could be the case that, due to increased transparency of the financial statements, the market would reward those firms which consolidate or disclose the VIE lessor, thus revealing the assets and liabilities associated with the lease. On the other hand, it could also be the case that the market might reward those firms that divest the synthetic lease arrangements by buy-out or refinancing, thus disentangling the firm from financing that may be perceived as “risky.” Thus, H2: A differential valuation impact will be experienced depending on the action taken by the firm regarding its synthetic lease. Due to the fact that it is unclear how the market should react, no directional prediction is made with regard to this hypothesis. Although off-balance sheet leases receive standard footnote disclosure and even though most of the sample firms consolidated the VIE leases upon adoption of FIN 46 (See Table 1), based on existing evidence that supplementary disclosure is significantly considered by the market, it seems reasonable that maximum risk disclosures (required under FIN 46) are valued by the market. Further, because these disclosures specifically refer to maximum risk, it seems reasonable that these disclosures should be negatively valued. Thus, H3: Post-FIN46, maximum risk disclosures are negatively related to market valuation. V: Sample Selection and Statistical Analysis To gather data on firms with synthetic lease VIEs, a 10-K Wizard search of annual reports filed in 2004 was undertaken. 2004 was the year of choice due to the fact that FIN 46(R) was adopted in December 2003, therefore the first 10-K reports filed under the complete pronouncement appeared in 2004. For the bulk of firms in the sample, the 10-K filed in 2004 represents the filing for the fiscal year ended in 2003. For ease of explanation, all 10-Ks filed in 16 2004 are referred to as the “2003” filing. Corresponding to this, the filing from the year before is referred to as the “2002” filing. That is, the “2003” filing is post-FIN 46 adoption and the “2002” filing is pre-FIN 46 adoption. Searching for all occurrences of “FIN 46” and “variable interest entity/entities,” this search initially revealed 148 firms which disclosed the impact of FIN 46 on a particular lease VIE. It should be noted that not all of these firms referred to these leases as “synthetic;” however, as all of these arrangements involved a VIE, it seems reasonable to expect that they were all similar in nature. Of these 148 firms, 21 lacked complete data for both 2002 and 2003 in either Compustat and/or CRSP and were eliminated from the sample, leaving 127 firms for analysis. To control for the impact of risk on valuation, a matched sample was also examined. This matched sample was chosen from the population of firms which disclosed future minimum lease payments in the 10-K filed in 2004 (Compustat Data 95>0). These firms were matched to the VIE firms based on the 2003 one-year beta estimate (estimated using the market model and value-weighted market returns). See Figure 2 for illustration of the change in accounting treatment for the samples examined in this study. To examine H1, and study whether recognized lease amounts are valued more strongly than disclosed lease amounts, methodology similar to Davis-Friday et al (1999) and Bell et al. (2002) is employed. Valuation models are examined for 2002 (pre-FIN 46), 2003 (post-FIN 46), and for both years combined: 17 Model #1: MVEit 1CONSTANT 2 BVAit 3 nBVLit 4 BETAit 5 AEARN it 6 NEGEARNit 7 MULTIPLE 8 REC _ LEASEit 9 DISC _ LEASEit it Where: MVE = per share price of stock (PRC from CRSP) three months (following DavisFriday et al, 1999) after the fiscal year end. Market price three months after the fiscal year end was chosen to allow the market adequate time to assimilate information about the impact of FIN 46. CONSTANT = 1/shares outstanding at fiscal year-end (following Bell, et al., 2002) BVA = total assets divided by shares outstanding at fiscal year-end. nBVL = total liabilities less consolidated lease VIE liability, divided by shares outstanding at fiscal year-end BETA = 12-month BETA for 2002 and 2003, estimated using the market model. Beta is incorporated to control for the impact that risk is expected to have on the market’s evaluation of additional obligations. AEARN = abnormal earnings computed as income before extraordinary items less expected earnings (prior year’s book value * .12) (following Bell et al., 2002), divided by shares outstanding at fiscal year-end. NEGAEARN = abnormal earnings, if negative, divided by shares outstanding at fiscal yearend. MULTIPLE = 1 if the firm disclosed more than one VIE in the context of the FIN 46 adoption. REC_LEASE = lease liability recognized on the balance sheet, either by consolidation of the VIE or purchase of the leased asset, as disclosed in the “new pronouncements” footnote. Divided by shares outstanding at fiscal year-end. DISC_LEASE = the present value of the disclosed future minimum lease payments (Compustat Data 95+ Data 389), assuming the life of the lease can be determined by dividing the total of the minimum lease payments by the average payment as determined by Data95/5, the incremental borrowing rate is 10% (following Ely, 1995), and the estimated total life of the lease is equal to total minimum payments divided by the average payment. Divided by shares outstanding at fiscal year-end. The method to evaluate DISC_LEASE was chosen (as opposed to an 8 * rental expense heuristic used in some studies) because, based on the information available, this most closely follows the method required when capitalizing capital lease liabilities and is also similar to the method utilized by Standard and Poor’s for rating purposes (Standard and Poor’s, 2006). Further, as it is not possible, in most cases, to assign an asset value to leases that receive only 18 operating lease disclosure, in order to compare like items, only the liability side of the consolidated leasing arrangements are extracted from the book values. While it is expected that both REC_LEASE and DISC_LEASE will be valued negatively, based on prior evidence, recognized lease liabilities (REC_LEASE) are expected to receive more weight (i.e. a larger coefficient) than disclosed lease liabilities (DISC_LEASE). Of the firms examined, six distinct actions (as categorized in Table 1) were taken following announcement of FIN 46. However, for purposes of this analysis, firms will either be considered to have directly “complied” with FIN 46 if they consolidated or disclosed the VIE and to have “not complied” if any other action was taken. To evaluate H2, as to whether firm action influences the market, two additional variables, COMPLY and NOCOMPLY are added to the basic model discussed above. Model 2: MVEit 1CONSTANT 2 BVAit 3 nBVLit 4 BETAit 5 AEARN it 6 NEGEARNit 7 MULTIPLE 8 REC _ LEASEit 9 DISC _ LEASEit 10 ACTION it 11 ACTION 2 it it Where: COMPLY = 1 if the firm consolidated or disclosed the VIE and 0 otherwise. NOCOMPLY = 1 if the firm restructured, purchased, consolidated then purchased or terminated the VIE To investigate H3, whether or not the additional “maximum risk” disclosure required under FIN 46 is valued by the market, the following model is considered: 19 Model 3: MVEit 1CONSTANT 2 BVAit 3 BVLit 4 BETAit 5 AEARN it 6 NEGAEARNit 7 MULTIPLEit 8 DISC _ LEASEit 9 MAX _ RISK it it Where: BVL = total liabilities, divided by shares outstanding at fiscal year-end MAX_RISK = For firms with significant, but not primary interest in the lessor VIE, the maximum exposure to risk disclosed in the notes to the financial statements. VI: Results and Conclusions As presented in Table 4, the initial examination of Model 1, pooling years 2002 and 2003, reveals that while REC_LEASE and DISC_LEASE (with coefficients of -0.61 and -0.14, respectively) are both negatively valued, consistent with existing evidence, REC_LEASE is more heavily valued and a t-test shows the difference between these two coefficients to be significant (t=5.85). Therefore, as predicted, disclosed lease liabilities are valued with less weight than are recognized liabilities. Yet, with the initial model, the coefficient on DISC_LEASE (-.14) is small and a significant departure from the expected value of 1.0. Considering perceived differences in reliability between disclosed and recognized items, this value could perhaps be explained. However, when an additional term, DISC_LEASE*MATCH, was allowed to enter the equation (so that the impact on valuation for the matched (non-VIE) firms could be examined separately), a different picture emerges. Curiously, in the pooled results, this coefficient (DISC_LEASE*MATCH) is significantly positive, with an estimated coefficient of 2.47. Further, this result holds true for both the pre-FIN 46 (2002, with an estimate of 1.93) and postFIN 46 (2003, with an estimate of 2.47) periods. Further, in 2002, while still negative, the 20 coefficient on DISC_LEASE for the all firms is insignificant. Such results would seem to indicate that, for the matched firms, disclosed leases are valued more positively (less negatively) than they are for the VIE firms. While this is an issue that warrants further examination, it is beyond the scope of the current study. In Table 5, the results of Model 2 are presented. For the COMPLY and NOCOMPLY variables, coefficients of 10.78 and 12.26, respectively, are estimated. From these results, it seems that “complying” with FIN 46 (that is, either consolidating or disclosing involvement in the VIE rather than divesting the firm’s interest) generates positive valuation implications not as large as actions by firms that did not directly comply with the pronouncement. However, as these effects are not statistically different from one another (t=0.20), it appears that the fact that a firm “complies” with FIN 46 does not statistically distinguish it from firms that do not “comply.” In Table 6, the results for Model 3 are presented. From the original model, MAX_RISK with an estimated coefficient of -0.21 clearly has negative implications (as expected) on firm valuation. Notice however, that this coefficient estimate is very similar to that found on earlier models estimating DISC_LEASE. Therefore, it appears that the market does not value more heavily the MAX_RISK disclosure than it does the DISC_LEASE amounts. Further, as can be seen from the expanded specification of this model (also presented in Table 6) the MAX_RISK disclosure is not incrementally informative above the DISC_LEASE amounts as the coefficient on MAX_RISK becomes insignificant once DISC_LEASE is added to the model. That is, while the maximum risk disclosures are valued by the market, they do not incrementally inform beyond the already required lease disclosures. A finding consistent throughout these results is that the control variable MULTIPLE is positive, in most cases, significantly so. Such a finding warrants further investigation as it seems 21 to perhaps indicate that the market either views these firms with multiple VIEs in a different manner due to the fact that they are involved with multiple VIEs, or perhaps because there is some determinant about these firms that causes them to be valued differently than single-VIE firms. Results of this study indicate that while disclosed future minimum lease payments are significantly valued by the market pre- and post-FIN 46, financial statement recognized lease liabilities are valued with substantially more weight following FIN 46. Further, while the new maximum risk disclosures required under FIN 46 are valued by the market, they do not incrementally add valuation information beyond the already required lease disclosures. Further results from this study also show that the market values operating leases related to firms with VIEs in a different manner than it values operating leases from firms with similar market risk, but without VIEs. Uncovering the underlying reason for this difference will likely involve further exploration of risk measures, financing choice, and other determinants of market valuation in this setting. Contrary to expectations, the fact that firms “complied” with FIN 46 did not seem to have any implication for firm valuation. However, this measure of firm behavior is not a refined one, and further examination of this issue may be warranted. Finally, while the maximum risk disclosures relating to lease VIEs are significant when considered alone, they do not incrementally add information for firm valuation when disclosed operating lease amounts are also considered. This is not a particularly surprising result due to the uniform nature and valuation of operating lease disclosures. However, for other firms that did not have uniform disclosures relating to their particular VIEs prior to FIN 46, it would be expected that the maximum risk disclosures add greater amounts of information. 22 In summary, while FIN 46 appears to have added incremental information when lease VIEs were consolidated, it does not appear to have added additional information when relationships with lease VIEs were merely disclosed. Such results should be of interest to regulators concerned with the impact of FIN 46 on market efficiency and to corporate managers concerned with the impact of financing and disclosure choice on market valuation. 23 Table 1 Descriptive Statistics Panel A: Firm SIC Composition Group VIE Firms Agriculture, forestry, and fishing (SIC Codes 01-09) 0 Mining and construction (SIC Codes 10-17) 4 Manufacturing (SIC Codes 20-39) 49 Transportation, communications, electric, gas, and sanitary services (SIC Codes 40-49) 24 Wholesale and retail trade (SIC codes 50-59) 20 Finance, insurance, and real estate (SIC Codes 60-67) 11 Services (SIC Codes 70-89) 19 Total Match Firms 4 10 57 Total 4 14 106 14 14 6 22 38 34 17 41 127 254 127 Panel B: Firm Action Action Consolidated the VIE lessor under the provisions of FIN 46 Disclosed a significant interest in a VIE lessor Bought the lease or otherwise purchased the property underlying the lease Consolidated the VIE lessor and subsequently purchased the associated property Restructured the lease so that it would qualify as an operating lease Terminated the lease Disclosed no effect from FIN 46 on the treatment of the lease Total Number of Firms 59 15 11 9 14 2 17 127 24 Table 2 Descriptive Statistics – Including both Pre- and Post-FIN 46 Adoption Periods In Millions of Dollars per Share Panel A: VIE Sample Variable Mean Std. Dev. Min. Max. MVE 25.63 28.49 .25 335 BVA 61.74 117.25 1.43 1056.33 BVL 46.70 91.38 .27 753.10 AEARN -7.73 29.74 -309.87 25.61 REC_LEASE .83 5.77 0 86.31 DISC_LEASE 6.83 18.72 .06 157.88 MAX_RISK 1.62 13.83 0 196.38 Panel B: Match Sample Variable Mean Std. Dev. Min. Max. MVE 17.07 15.67 .15 80.25 BVA 19.54 22.06 .11 125.25 BVL 10.83 14.89 .05 78.77 AEARN -6.01 14.01 -113.04 6.95 REC_LEASE 0 0 0 0 DISC_LEASE 1.13 2.06 0 11.97 0 0 0 0 MAX_RISK _____________________________ MVE BVA BVL AEARN = = = = per share price three months following the firms fiscal year end. book value assets at fiscal year end. book value liabilities at fiscal year end. abnormal earnings, computed as income before extraordinary items (Compustat Data 18) less expected return (12% (following Bell, et al. 2002) * book value of equity at previous fiscal year end). REC_LEASE = liability recorded as a result of consolidating the lessor VIE. DISC_LEASE = the present value of the disclosed future minimum lease payments (Compustat Data 95 + Data 389), assuming the life of the lease can be determined by dividing the total of the minimum lease payments by the average payment as determined by Data 95/5, the incremental borrowing rate is 10% (following Ely, 1995) and the estimated total life of the lease is equal to total minimum payments divided by the average payment. MAX_RISK = disclosed maximum risk exposure related to significant VIEs in which the firm is not the primary beneficiary. 25 Table 3 Correlation Analysis Pearson Correlation Coefficients (p-values) MVE MVE BVA nBVL AEARN BETA REC_LEASE DISC_LEASE MAX_RISK BVA nBVL AEARN BETA REC_LEASE DISC_LEASE 1.000 .6696 (.0000) .5338 (.0000) .9667 (.0000) 1.000 -.0009 (.9847) -.1569 (.0004) .1880 (.0000) .1716 (.0001) -.0472 (.2883) -.0373 (.4014) .1539 (.0005) .3899 (.0000) -.0302 (.4969) -.0102 (.8194) .0590 (.1841) .4015 (.0000) -.0128 (.7729) -.0166 (.7082) -.0360 (.4186) -.0182 (.6821) .1617 (.0003) .0529 (.2338) 1.000 -.0264 (.5525) .0897 (.0433) .1158 (.0090) .0143 (.7480) .1640 (.0002) -.0081 (.8561) .5983 (.0000) MAX_RISK 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 1.000 __________________________ MVE BVA nBVL AEARN = = = = BETA = REC_LEASE = DISC_LEASE = MAX_RISK = per share price three months following the firms fiscal year end. book value assets at fiscal year end. total liabilities less consolidated lease VIE liability, divided by shares outstanding at fiscal year-end. abnormal earnings, computed as income before extraordinary items (Compustat Data 18) less expected return (12% (following Bell, et al. 2002) * book value of equity at previous fiscal year end). 12-month BETA for 2002 and 2003, estimated using the market model. Beta is incorporated to control for the impact that risk is expected to have on the market’s evaluation of additional obligations. liability recorded as a result of consolidating the lessor VIE. the present value of the disclosed future minimum lease payments (Compustat Data 95 + Data 389), assuming the life of the lease can be determined by dividing the total of the minimum lease payments by the average payment as determined by Data 95/5, the incremental borrowing rate is 10% (following Ely, 1995) and the estimated total life of the lease is equal to total minimum payments divided by the average payment. disclosed maximum risk exposure related to significant VIEs in which the firm is not the primary beneficiary. 26 Table 4 Model 1 MVEit 1CONSTANT 2 BVAit 3 nBVLit 4 BETAit 5 AEARN it 6 NEGAEARN 7 MULTIPLE 8 REC _ LEASEit 9 DISC _ LEASEit it 2002 CONSTANT -14.54 (-1.41) -20.44* (-2.01) -15.32 (-1.21) BVA 0.61** (13.61) 0.60** (13.84) 1.00** (18.32) nBVL -0.58** (-10.19) -0.57** (-10.23) BETA 2.51** (4.90) AEARN Estimate (p-value) 2003 -23.12 (-1.89) Pooled -15.46 (-1.83) -22.60** (-2.72) 0.99** (18.84) 0.80** (21.79) 0.79** (22.27) -1.02** (-14.74) -1.01** (-15.08) -0.79** (-16.99) -0.78** (-17.22) 2.29** (4.53) 3.45** (6.66) 3.10** (6.15) 3.09** (8.15) 2.79** (7.52) 4.68** (6.73) 4.40** (6.45) 2.76** (4.70) 2.64** (4.67) 3.03** (6.73) 2.85** (6.53) -4.76** (-6.80) -4.48** (-6.54) -2.81** (-4.76) -2.70** (-4.75) -3.09 (-6.83) -2.92** (-6.64) MULTIPLE 11.26** (3.41) 11.98** (3.77) 12.12** (4.12) 12.69** (4.45) REC_LEASE -1.05** (-5.04) -.99** (-4.92) -0.61** (-3.31) -0.56** (-3.13) -0.30** (-3.32) -0.31** (-4.05) -.14* (-2.43) -.16** (-2.79) 254 .8071 2.51** (4.05) 254 .8120 508 .7571 2.47** (5.83) 508 .7726 NEGAEARN DISC_LEASE -.01 (-0.17) -.03 (-.45) 254 .7252 1.93** (3.66) 254 .7398 DISC_LEASE*MATCH n R-Squared 27 ________________________ CONSTANT BVA nBVL BETA = = = = AEARN = NEGAEARN MULTIPLE REC_LEASE = = = DISC_LEASE = DISC_LEASE* MATCH = 1/shares outstanding at fiscal year-end (following Bell, et al., 2002) total assets divided by shares outstanding at fiscal year-end. total liabilities less consolidated lease VIE liability, divided by shares outstanding at fiscal year-end 12-month BETA for 2002 and 2003, estimated using the market model. Beta is incorporated to control for the impact that risk is expected to have on the market’s evaluation of additional obligations. abnormal earnings computed as income before extraordinary items less expected earnings (prior year’s book value * .12) (following Bell et al., 2002), divided by shares outstanding at fiscal year-end. abnormal earnings, if negative, divided by shares outstanding at fiscal year-end. 1 if the firm disclosed more than one VIE in the context of the FIN 46 adoption. lease liability recognized on the balance sheet, either by consolidation of the VIE or purchase of the leased asset, as disclosed in the “new pronouncements” footnote. Divided by shares outstanding at fiscal year-end. the present value of the disclosed future minimum lease payments (Compustat Data 95+ Data 389), assuming the life of the lease can be determined by dividing the total of the minimum lease payments by the average payment as determined by Data95/5, the incremental borrowing rate is 10% (following Ely, 1995), and the estimated total life of the lease is equal to total minimum payments divided by the average payment. Divided by shares outstanding at fiscal year-end. Interaction between DISC_LEASE and MATCH where MATCH = 1 if the firm is from either of the matched samples (NME and GEN) and 0 if the firm is part of the VIE sample. 28 Table 5 Model 2 MVEit 1CONSTANT 2 BVAit 3 nBVLit 4 BETAit 5 AEARN it 6 NEGEARNit 7 MULTIPLE 8 REC _ LEASEit 9 DISC _ LEASEit 10 ACTION it 11 ACTION 2 it it Estimate (p-value) CONSTANT -4.43 (-0.37) 0.96** (18.28) -0.98** (-14.76) 2.41** (4.61) 2.19** (3.87) -2.20** (-3.87) 4.94 (1.46) BVA nBVL BETA AEARN NEGAEARN MULTIPLE REC_LEASE -1.16** (-5.81) -0.31** (-3.61) 10.78** (4.44) 12.26** (4.29) 254 .8293 DISC_LEASE COMPLY NOCOMPLY n R-squared _____________________________ CONSTANT BVA nBVL BETA = = = = AEARN = NEGAEARN MULTIPLE REC_LEASE = = = DISC_LEASE = COMPLY NOCOMPLY = = 1/shares outstanding at fiscal year-end (following Bell, et al., 2002) total assets divided by shares outstanding at fiscal year-end. total liabilities less consolidated lease VIE liability, divided by shares outstanding at fiscal year-end 12-month BETA for 2002 and 2003, estimated using the market model. Beta is incorporated to control for the impact that risk is expected to have on the market’s evaluation of additional obligations. abnormal earnings computed as income before extraordinary items less expected earnings (prior year’s book value * .12) (following Bell et al., 2002), divided by shares outstanding at fiscal year-end. abnormal earnings, if negative, divided by shares outstanding at fiscal year-end. 1 if the firm disclosed more than one VIE in the context of the FIN 46 adoption. lease liability recognized on the balance sheet, either by consolidation of the VIE or purchase of the leased asset, as disclosed in the “new pronouncements” footnote. Divided by shares outstanding at fiscal year-end. the present value of the disclosed future minimum lease payments (Compustat Data 95+ Data 389), assuming the life of the lease can be determined by dividing the total of the minimum lease payments by the average payment as determined by Data95/5, the incremental borrowing rate is 10% (following Ely, 1995), and the estimated total life of the lease is equal to total minimum payments divided by the average payment. Divided by shares outstanding at fiscal year-end. 1 if the firm consolidated or disclosed the VIE and 0 otherwise. 1 if the firm restructured, purchased, consolidated the purchased, or terminated the VIE. 29 Table 6 Model 3 MVEit 1CONSTANT 2 BVAit 3 BVLit 4 BETAit 5 AEARN it 6 NEGAEARNit 7 MULTIPLEit 8 MAX _ RISK it it Estimate (p-value) CONSTANT BVA BVL BETA AEARN NEGAEARN MULTIPLE MAX_RISK Original Model -16.19 (-1.28) 0.97** (17.83) -0.99** (-14.28) 3.31** (6.43) 2.43** (4.25) -2.48** (-4.31) 11.95** (3.59) -0.21** (-2.70) DISC_LEASE n R-squared 254 .8043 Expanded Model -15.11 (-1.20) 1.02** (17.14) -1.04** (-14.30) 3.48** (6.71) 2.88** (4.73) -2.94** (-4.80) 10.74** (3.20) 0.14 (0.76) -0.44* (-2.08) 244 .8076 _____________________________ CONSTANT BVA nBVL BETA = = = = AEARN = NEGAEARN MULTIPLE MAX_RISK = = = DISC_LEASE = 1/shares outstanding at fiscal year-end (following Bell, et al., 2002) total assets divided by shares outstanding at fiscal year-end. total liabilities less consolidated lease VIE liability, divided by shares outstanding at fiscal year-end 12-month BETA for 2002 and 2003, estimated using the market model. Beta is incorporated to control for the impact that risk is expected to have on the market’s evaluation of additional obligations. abnormal earnings computed as income before extraordinary items less expected earnings (prior year’s book value * .12) (following Bell et al., 2002), divided by shares outstanding at fiscal year-end. abnormal earnings, if negative, divided by shares outstanding at fiscal year-end. 1 if the firm disclosed more than one VIE in the context of the FIN 46 adoption. For firms with significant, but not primary interest in the lessor VIE, the maximum exposure to risk disclosed in the notes to the financial statements. the present value of the disclosed future minimum lease payments (Compustat Data 95+ Data 389), assuming the life of the lease can be determined by dividing the total of the minimum lease payments by the average payment as determined by Data95/5, the incremental borrowing rate is 10% (following Ely, 1995), and the estimated total life of the lease is equal to total minimum payments divided by the average payment. Divided by shares outstanding at fiscal year-end. 30 Figure 1 Typical Synthetic Lease Structure Adapted from Little (2002) Third Party Seller Title Purchase Price Loan Proceeds Loan Lender Lessee (Company) Lessor (SPE) Debt Service Rent Return Equity Equity Participant 31 Figure 2 Pre-/Post-VIE Treatment in the Sponsor’s Financial Statements and Notes to the Financial Statements Panel A: Pre-FIN 46 Sub-Sample Partition Accounting Treatment Consolidated the VIE lessor under the provisions of FIN 46 Disclosed a significant interest in a VIE lessor Bought the lease or otherwise purchased the property underlying the lease/ Consolidated the VIE lessor and subsequently purchased the -Rent expense reported on the income statement. associated property -Future minimum operating lease payments Terminated the lease disclosed in the notes to the financial statements. Restructured the lease so that it would qualify as an operating lease Disclosed no effect from FIN 46 on the treatment of the lease Matched sample Panel B: Post-FIN 46 Sub-Sample Partition Accounting Treatment Consolidated the VIE lessor under the provisions -Assets and liabilities of the VIE consolidated onto of FIN 46 the balance sheet. -Depreciation and interest expense reported on the income statement. -Details of the relationship with the VIE and the VIE’s financing structure disclosed in the notes to the financial statements. Disclosed a significant interest in a VIE lessor -Rent expense reported on the income statement. -Future minimum operating lease payments disclosed in the notes to the financial statements. -Details of the relationship with the VIE and the VIE’s financing structure disclosed in the notes to the financial statements. -The maximum exposure to loss as a result of involvement with the VIE disclosed in the notes to the financial statements. Bought the lease or otherwise purchased the -Formerly leased asset (and any associated debt) property underlying the lease/ Consolidated the appears as an ordinary asset and liability on the VIE lessor and subsequently purchased the balance sheet. associated property -Depreciation and any interest expense reported on the income statement. Terminated the lease -Formerly leased asset no longer appears in the financial statements or notes. Restructured the lease so that it would qualify as an operating lease -Rent expense reported on the income statement. Disclosed no effect from FIN 46 on the treatment -Future minimum operating lease payments of the lease disclosed in the notes to the financial statements. Matched sample 32 Works Cited AAA Financial Accounting Standards Committee. 2003. Comments on the FASB’s proposals on consolidating special-purpose entities and related standard-setting issues. Accounting Horizons 17(2): 161-173. AAA Financial Accounting Standards Committee. 2001. Evaluation of the lease accounting proposed in G4+1 special report. Accounting Horizons 15(3): 289-298. Ahmed, A., E. Kilic, G. Lobo. 2006. Does recognition versus disclosure matter? Evidence from value-relevance of banks’ recognized and disclosed derivative financial instruments. The Accounting Review 81(3): 567-588. Barth, M., W. Beaver, and W. Landsman. 1996. Value-relevance of banks’ fair value disclosures under SFAS No. 107. The Accounting Review 71(4): 513-537. Bauman, M. 2003. The impact and valuation of off-balance-sheet activities concealed by equity method accounting. Accounting Horizons 17(4): 303-314. Bell, T., W. Landsman, B. Miller, and S. Yeh. 2002. The valuation implications of employee stock option accounting for profitable computer software firms. The Accounting Review 77(4): 971-996. Botosan, C. 1997. Disclosure level and the cost of equity capital. The Accounting Review. 72(3): 323-350. Botosan, C. and M. Plumlee. 2002. A re-examination of disclosure level and the expected cost of equity capital. Journal of Accounting Research 40(1): 21-41. Danvers, K., A. Reinstein, and L. Jones. 2003. Financial performance effects of synthetic leases. Briefings in Real Estate Finance 3(2): 131-146. Davis-Friday, P., L. Folami, C. Liu, and H. Mittelstaedt. 1999. The value relevance of financial statement recognition vs. disclosure: evidence from SFAS No. 106. The Accounting Review 74(4): 403-423. Dorsey, T. 2000. Maximizing profits with a synthetic lease. The Appraisal Journal January: 93-96. Ely, K. 1995. Operating lease accounting and the market’s assessment of equity risk. Journal of Accounting Research 33(2): 397-415. Evans, M. 1996. Synthetic real estate: Corporate America goes off balance sheet. Journal of Property Management 61(6): 49-50. 33 Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). 2003. Consolidation of Variable Interest Entities an Interpretation of ARB No. 51. FIN 46 (Revised December 2003). Norwalk, CT: FASB. Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). 1984. Recognition and Measurement in Financial Statements of Business Enterprises. SFAC No. 5. Norwalk, CT: FASB. Graham, R., C. Lefanowica, and K. Petroni. 2003. The value relevance of equity method fair value disclosures. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting 30(7)&(8): 1065-1089. Imhoff, E., R. Lipe, and D. Wright. 1991. Operating leases: impact of constructive capitalization. Accounting Horizons March: 51-63. Imhoff, E., R. Lipe, and D. Wright. 1993. The effects of recognition versus disclosure on shareholder risk and executive compensation. Journal of Accounting, Auditing, and Finance 8(4): 335-368. Imhoff, E., R. Lipe, and D. Wright. 1995. Is footnote disclosure an adequate alternative to financial statement recognition? The Journal of Financial Statement Analysis Fall: 70-81. Johnson, L. 1992. Research on disclosure. Accounting Horizons 6(1): 101-103. Koonce, L., M.L. McAnnally, M. Mercer 2005. How do investors judge the risk of financial items? The Accounting Review 80(1): 221-241. Libby, R., M. Nelson, and J. Hunton. 2006. Recognition v. disclosure, auditor tolerance for misstatement and the reliability of stock-compensation and lease information. Journal of Accounting Research 44(3): 533-560. Little, N. 2002. Overview of synthetic leasing. In N. Little (ed.) Synthetic Lease Financing: Keeping Debt Off the Balance Sheet (pp. 1-24). Chicago: American Bar Association. Muto, S. and M. Veverka. 1997 (April 2). Firms flock to type of leasing. The Wall Street Journal p. CA1. Ratner, A. 1996. Synthetic leasing: too good to be ignored. National Real Estate Investor 38(8): 103-104. Schipper, K. August 2005. Required Disclosure in Financial Reports. Presidential Lecture to the 2005 American Accounting Association Annual Meeting. San Francisco, CA. Scott, W.R. 2003. Financial Accounting Theory (3rd ed.) Toronto: Prentice Hall. 34 Securities and Exchange Commission. 2005. Report and recommendations pursuant to Section 401(c) of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 on arrangements with off-balance sheet implications, special purpose entities, and transparency of filings of issuers. Available on-line at http://www.sec.gov/news/studies/soxoffbalancerpt.pdf. Soroosh, J. and J. Ciesielski. 2004. Accounting for special purpose entities revised: FASB Interpretation 46(R). The CPA Journal. 74(7): 30-37. Standard and Poor’s Rating Methodology: Evaluating the Issuer. Retrieved April 21, 2006 from http://www2.standardandpoors.com. 35