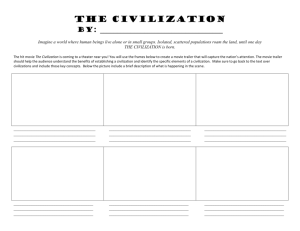

Civilization and Its Discontents

advertisement