Survival-enhancing learning in the Manhattan Hotel Industry, 1898

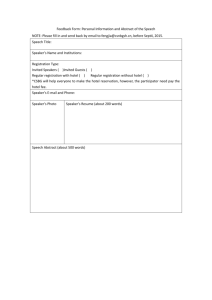

advertisement