INTRODUCTION TO FINANCE - Spears School of Business

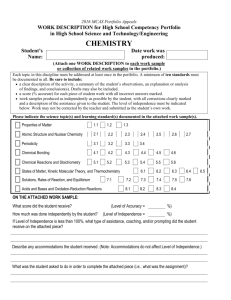

advertisement

PORTFOLIO MANAGEMENT BADM 744 – 001, Classroom AB 201 and AB 312 Department of Managerial Sciences College of Business Administration University of Nevada at Reno ALI NEJADMALAYERI Ansari Business Building, Room 401B Office Hours: Monday and Wednesday 5:30 – 6:45 Phone: 784 – 6993 ext. 306 Email: aliala@unr.edu COURSE OBJECTIVE: This course provides a conceptual and theoretical foundation for the activities of prototypical professional investment managers. Although the focus of the course is on the management of institutional (e.g., pension funds and insurance companies) portfolios, the basic investment management principles are also applicable to individual investors. Using a combination of academic discussions, practitioner-oriented readings, case studies, Excel-based assignments, and a simulated investment game, students will be introduced to both the conventional wisdom and state-of-the-art methods used in performing many of the mutual fund management functional tasks, including security research, economic forecasting, asset allocation, and portfolio rebalancing. Since this course aims to provide a thorough understanding of the components of equity investment management, it is especially relevant to students planning to eventually work in a financial capacity in business. In particular, we hope that by the end of the semester, students will be able to start the lengthy process of obtaining the professional designation of Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA®). COURSE MATERIAL: There are three required references for this course. The major reference for the course is “Investment Analysis and Portfolio Management, 7th Ed.”, by Frank K. Reilly & Keith C. Brown (hereafter RB). The second important reference for the course is a collection of four Harvard Business School cases. These cases are available at the university bookstore. The last reference for the course is a collection of articles from major practitioners’ journals such as Financial Analyst Journal and the Journal of Portfolio Management. The University library’s electronic journals site has access to these journals. You can also click in the appropriate link for each of these articles, which is provided in the course page at: http://equinox.unr.edu/homepage/aliala/public_html/newfin521.htm . There are also additional optional references for this course, as follows: “The Intelligent Investor”, by Benjamin Graham “Security Analysis”, by Benjamin Graham and David Dodd “The Intelligent Asset Allocator”, by William J. Bernstein I also strongly urge you to follow the popular financial press and media such as: Programs like Kudlow & Cramer; Louis Rukeyser's Wall Street, etc. Magazines like Business Week, Money, Fortune, Smart Money, Bloomberg Personal, etc. Papers like Wall Street Journal, Financial Times, Investor Business Daily PREREQUISITE: It is assumed that students will have completed the relevant prerequisite courses in finance, accounting, and statistics. Students who wish to take this course must have already passed these courses: Financial Management (BADM 741) and Investment (BADM 743). A financial calculator is highly recommended for this course, such as an HP 10B, HP 12C or TI BII. CLASSROOM: The official 165-minute allotted time is separated into two 75-minute sessions with 15 minute break in between. For the first session, we will meet at the COBA computer lab, room 312. We will then move to AB 201 for the remainder of the class. GRADES: Your final grade for this course is determined as follows: Grade Activity 1 Comprehensive Final Exam 3 Take-home Mid-term Exams 10 Summary Reports 5 Homework Assignments 4 Case Studies Portfolio Manager Game Percentage Point Range 89.5% – 100.0% 79.5% – 89.4% 69.5% – 79.4% 59.5% – 69.4% < 59.5% Percentage 15 30 10 15 20 10 Final Letter Grade A B C D F There will be a total of three equally weighted examinations – two interim tests and the final exam. The final exam is comprehensive and mandatory. All exams combined represent 45% of the final grade of the course. Students must take all of the interim and final exams. If for some reason a student must miss an exam, the student must discuss the matter with the instructor before the day of the exam. Otherwise, the student will receive a “zero” for the missed test. Under any circumstance, NO MAKE–UP TESTS will be given. Only university–authorized absences will be accepted. In such a case, the grade for that exam will be replaced by the grade for the relevant part in the final exam. The final exam is comprehensive and all students have to take the exam. THE FINAL EXAM WILL BE GIVEN ON WEDNESDAY, MAY 12, 2004 DURING THE TIME PERIOD OF 7:00 P.M. – 9:00 P.M. AS DESIGNATED BY THE SPRING 2004 CLASS SCHEDULE. The remaining portion of the final course grade is comprised of ten article summary reports, five assignments, four cases and one game. The link to the relevant articles can be found in the course page. For each class, student must read two assigned articles and write one “Report” of the length no longer than three pages. Every student should be prepared to discuss all of the articles in class. Grades for these grade activities are based on both the quality of reports as well as the class discussions. These reports account for 10% of your total grade point. Additionally, five Excel-based homework assignments will be given in appropriate time, usually at the end of each chapter, to help students apply the concepts in class and textbook in real settings. These assignments are designed to make you (1) learn how and where to find raw data, (2) become proficient users of Excel and build rather complicated models with it, and (3) analyze raw data and impute valuable information. These assignments account for 15% of your total grade point. During the semester we will also analyze and discuss four Harvard business cases. Detailed case instructions are provided in the later part of the syllabus. These instructions can also be found in the course page. For each case, students must read the instructions and write a “Summary Report” of no more than three pages in length. The grades for these activities are based on the quality of the report and class participation. These cases account for 20% of your total grade point. Lastly, during the semester, groups of four to five will manage four fund tracks: large-growth, largevalue, small-growth, and small-value funds. Each group is responsible for (1) selecting stock and (2) allocation of capital. Each group must choose at least 40 and at most 80 stocks for all four funds. No fund can contain less than 10 stocks. Last section explains in details how this game is played and how your performance will be evaluated. The game accounts for 10% of your total grade point. IN-CLASS RULES: Students are not allowed to have pagers, cellular phones, laser pointers, electronic games, musical devices, or any other device, which may distract any other student or instructor. Respect is expected at all times and no cursing will be tolerated. ATTENDANCE POLICY: Students are expected to attend each class. Attendance will be taken at the beginning of each class. Students who must miss be absent from a class are responsible for securing any and all course work missed from the other students in the class. DISABILITY ACCOMMODATIONS: If a student requires accommodations based on disability, the student should meet with the instructor during the first week of the semester. STATEMENT OF ACADEMIC DISHONESTY: Academic dishonesty is an absolutely unacceptable mode of conduct and will not be tolerated in any form. All persons involved in academic dishonesty will be disciplined in accordance with University regulations and procedures. We strictly adhere to the guidelines set forth by the University Student Conduct policies. COURSE SCHEDULE: Date Jan 21 Jan 28 Agenda Fundamentals: Risk and Returns o Chapter 8 o Chapter 9 Articles: AR1 & AR2 Feb 04 Feb 11 Security Analysis: Introduction o Chapter 11 o Chapter 12 Articles: AR3 & AR4 INTRODUCTION TO MONEY TOOLS Security Analysis: Market and Industry o Chapter 13 o Chapter 14 Articles: AR5 & AR6 PORTFOLIO GAME BEGINS Assignments Due† HW 1 Report 1 (AR1 & AR2) Report 2 (AR3 & AR4) Report 3 (AR5 & AR6) ALL REQUIRED FILINGS DUE Valuation: Fundamental vs. Technical o Chapter 15 Articles: AR7 & AR8 TAKE-HOME EXAM 1 o CHAPTERS 8, 9, 11 – 15 o ARTICLES 1 – 8 Feb 18 TAKE-HOME EXAM 1 DUE DATE Case 1: Interco TAKE-HOME EXAM 1 Case 1 Summary Report Feb 25 Asset Allocation: Introduction o Chapter 2 o Chapter 7 o Chapter 17 Articles: AR9 & AR10 Report 5 (AR9 & AR10) Asset Allocation: Professional Management o Chapter 25 Articles: AR11 & AR12 FIRST PORTFOLIO GAME REPORT Report 6 (AR11 & AR12) FILINGS AND RECORDS Mar 03 Mar 10 Performance Evaluation o Chapter 5 o Chapter 26 Articles: AR13 & AR14 TAKE-HOME EXAM 2 o CHAPTERS 2, 5, 7, 17, 25 & 26 o ARTICLES 9 – 14 HW 2 Report 4 (AR7 & AR8) HW 3 Report 7 (AR13 & AR14) Mar 24 TAKE-HOME EXAM 2 DUE DATE Case 2: Massachusetts Financial Services TAKE-HOME EXAM 2 Case 2 Summary Report Mar 31 Bonds and Bond Portfolio Management o Chapter 19 o Chapter 20 Articles: AR15 & AR16 Report 8 (AR15 & AR16) GUEST SPEAKER Case 3: Arbitrage in Government Bonds Case 3 Summary Report Derivatives and Portfolio Management o Chapter 21 (pp. 888 – 894) o Chapter 22 (pp. 909 – 912; 915 – 941) Articles: AR17 & AR18 SECOND PORTFOLIO GAME REPORT TAKE-HOME EXAM 2 o CHAPTERS 19 – 22 o ARTICLES 15 – 18 Apr 21 TAKE-HOME EXAM 3 DUE DATE Case 4: Leland O’Brien Rubinstein Associates Apr 28 Behavioral Finance o Articles: AR19, AR20, AR21 & AR22 Report 10 (AR19 – AR22) HW 5 PORTFOLIO GAME ENDS LAST PORTFOLIO GAME REPORT ALL FILINGS AND RECORDS GAME PERFORMANCE EVALUATION Apr 07 Apr 14 May 12 † HW 4 Report 9 (AR17 & AR18) FILINGS AND RECORDS TAKE-HOME EXAM 3 Case 4 Summary Report Final Exam: Comprehensive CFA Style Exam Time: 7:00 p.m. – 9:00 p.m.; Location: AB 201 All homework assignments will be distributed a week earlier. LIST OF ARTICLES: Article AR1 AR2 AR3 AR4 Reference: Robert D. Arnott and Peter L. Bernstein; What Risk Premium is ‘Normal’?; Financial Analysts Journal, Mar/Apr2002; Vol. 58 Issue 2, pp. 64 – 86 Edward M Miller; Why the low returns to beta and other forms of risk; Journal of Portfolio Management, New York; Winter 2001; Vol. 27, Issue 2; pp. 40 – 56 Robert D. Arnott and William A. Copeland; The Business Cycle and Security Selection; Financial Analysts Journal, Mar/Apr85, Vol. 41 Issue 2, pp. 26 – 33 Joe Brocato and Steve Steed; Optimal Asset Allocation Over the Business Cycle”; Financial Review, Aug1998, Vol. 33 Issue 3, pp.129 – 149 AR5 AR6 AR7 AR8 AR9 AR10 AR11 AR12 AR13 AR14 AR15 AR16 AR17 AR18 AR19 AR20 AR21 AR22 Erik Lie and Heidi J. Lie; “Multiples Used to Estimate Corporate Value.” Financial Analysts Journal, Mar/Apr2002, Vol. 58 Issue 2, pp. 44 – 56 C. Barry White; What P/E Will the U.S. Stock Market Support? Financial Analysts Journal, Nov/Dec2000, Vol. 56 Issue 6, p30 – 39 Eric H Sorensen et al.; The decision tree approach to stock selection; Journal of Portfolio Management; Fall 2000; Vol. 27, Issue 1; pp. 42 – 53 Hemang Desai and Liang Bing; Do All-Stars Shine? Evaluation of Analyst Recommendations; Financial Analysts Journal, May/Jun2000, Vol. 56 Issue 3, pp. 20 – 30 Felix Schirripa; An optimal frontier; Journal of Portfolio Management, Summer 2000; Vol. 26, Issue 4; pp. 29 – 41 Parvez Ahmed; Style investing: Incorporating growth characteristics in value stocks; Journal of Portfolio Management, Spring 2001; Vol. 27, Issue 3; pp. 47 – 60 Gerald W. Buetow Jr ; The benefits of rebalancing; Journal of Portfolio Management, Winter 2002; Vol. 28, Issue 2; pp. 23 – 33 Patrick Dennis and Steven B. Perfect; The Effects of Rebalancing on Size and Book-to-Market Ratio Portfolio Returns; Financial Analysts Journal, May/Jun95, Vol. 51 Issue 3, p47 – 58 Robert M Korkie; What's a portfolio manager worth?; Journal of Portfolio Management, Winter 2002; Vol. 28, Issue 2; pp. 65 – 64 James L. Davis; Mutual Fund Performance and Manager Style. Financial Analysts Journal, Jan/Feb2001, Vol. 57 Issue 1, p19 – 28 Jouke Hottinga; Successful factors to select outperforming corporate bonds; Journal of Portfolio Management, Fall 2001; Vol. 28, Issue 1; pp. 88 – 102 Lev Dynkin; Value of skill in security selection versus asset allocation in credit markets; Journal of Portfolio Management, Fall 2000; Vol. 27, Issue 1; pg. 20 – 42 Todd Miller; Beating index funds with derivatives; Journal of Portfolio Management, May 1999; pg. 75 – 88 Clifford Asness; Do hedge funds hedge?; Journal of Portfolio Management, Fall 2001; Vol. 28, Issue 1; pp. 6 – 20 Mark Grinblatt, Sheridan Titman, and Russ Wermers; Momentum Investment Strategies, Portfolio Performance, and Herding: A Study of Mutual Fund Behavior, American Economic Review, December 1995, Vol. 85 Issue 5, p1088 – 1105 D. Hilton; The Psychology of Financial Decision-Making: Applications to Trading, Dealing, and Investment Analysis; Journal of Psychology and Financial Markets, 2001, Vol. 2 Issue 1, pp. 37 – 54 Hersh Shefrin and Meir Statman; The Disposition to Sell Winners Too Early and Ride Losers Too Long: Theory and Evidence; Journal of Finance, Jul 85, Vol. 40 Issue 3, p777 – 790 Robert Shiller; Bubbles, Human Judgment, and Expert Opinion, Financial Analysts Journal, MayJune 2002, Vol. 58 Issue 3, pp. 18 – 27 Note that these hyperlinks take you to html text version of the article. If you like to see the article in original (pdf) format, at the bottom of each page there is link to “Page Image”. CASES: To make a connection between all the theoretical knowledge and real world “how-to-do things”, we will analyze four cases involving some the most notable topics: valuation, fixed income securities, portfolio insurance, and performance measurement. You are required to study these cases before hand and prepare a “Summary Report” of the length no more than three double-spaced typewritten pages. You may include an addendum containing Excel files, references, etc. In the following, you will find a detailed instruction for each case. __________________________________________________________________________________ Case 1. Valuation: Interco SYNOPSIS: This case is aimed at helping you to understand and appreciate the importance of assumptions and internal consistency in a valuation project. Additionally, the case provides you with an excellent example of how different methods of valuation work. GENERAL OBJECTIVES: Practice valuation techniques and become closely familiar with them Contrast and compare these methods. Understand their strengths and weaknesses. Ask how fundamental assumptions such the risk-free rate, the cost of capital, the optimal capital structure, the interlink between economic environment and firm’s performance, etc. influence your assessment of the firm’s value Put things in perspective by analyzing the role of parties involved in a take-over bid. PERTINENT QUESTIONS: What do you think of Interco? o e.g., firm’s goals, strategies repositioning program, etc. How do you assess Interco’s financial performance? o i.e., the relation between the take-over bid and the firm’s financial health What do you think of different valuation methods? o e.g., premium paid, comparable transaction cost, discounted cash flow, etc. How do these models help the board to respond to the take-over bid? How to assess different parties involved? o i.e., the board of directors, management, the Rales bothers, Drexel, etc. __________________________________________________________________________________ Case 2. Performance Measures: Massachusetts Financial Services SYNOPSIS: This case is aimed at helping you to understand the implications of different approaches to the compensation design in the investment industry. Moreover, the case gives an excellent example of how maintaining two different evaluation scheme under the same roof can challenging. Lastly, the case lays out a more general problem of motivating constituents to invest their human capital in an organization without ever expecting to increase their own value in the outside labor markets. GENERAL OBJECTIVES: Analyze the relative advantages and disadvantages of subjective as opposed to objective performance evaluation in motivating people to generate positive results Discuss the challenges of a subjective evaluation system Understanding the difficulty of using both evaluation systems within one organization Appreciating the difficulty of motivating people to undertake firm specific human capital investment (i.e., motivate people to invest in the organization without expecting to increase their labor market competitive value) PERTINENT QUESTIONS: Why do MFS managers think the portfolio managers’ market is a “star” market? o i.e., is there any difference between this labor market and others? What are the characteristics of the MFS’s “star” system? o i.e., what type of workers does the system attract? What are, if any, the differences between MFS’s and HMC’s performance evaluation? o e.g., compared to HMC, what type of people does MFS attracts? What weakness and strengths does MFS system contain? o i.e., does the compensation scheme motivate people? What are potential problems created by the MFS’s compensation system? How do you assess the future of the MFS’s hedge fund? o e.g., is the firm going be able to attract the right people and generate results? __________________________________________________________________________________ Case 3. Bonds: Arbitrage in the Government Bond Markets? SYNOPSIS: This case is aimed at helping you to practice with basic bond pricing models and understand the pertinence of the notion of arbitrage. The case should help you to gain insight into the designing and pricing securities using the absence of arbitrage principle. Additionally, the case provides you with a excellent example of how an otherwise risk-free security traded in a presumably perfect, liquid, deep market can cause price discrepancies which violates the most sacred cornerstones of finance. GENERAL OBJECTIVES: Become familiar with the workings of the Treasury bond market. Understand the very notion of arbitrage and the role of arbitrage in security pricing. Understand what “synthetic” security means and how and why one can be created. Understand the meaning of embedded options. What is the right to call? Is there an optimal time to exercise the right to call? When? PERTINENT QUESTIONS: How should one value a callable bonds using synthetic bonds? o e.g., create the two synthetic bonds in the case On January 7, 1991, how much would it have cost to create these bonds? How does Thompson exploit any mispricing? o i.e., on January 7, 1991, how could he benefit from holders of 8.25 May ‘00-’05? What can underlie the odd relative pricing of the bonds Thompson is considering? Why does the Treasury issue callable bonds? o i.e., when should the Treasury call or redeem these bonds? Why does a corporation issue callable bonds? o i.e., when should the corporation call or redeem these bonds? SUPPLEMENTS: 1. Longstaff, Francis A., Are Negative Option Prices Possible? The Callable U.S. TreasuryBond Puzzle, Journal of Business, Vol. 65, No. 4, Oct., 1992, pp. 571-592. 2. Jordan, Bradford D; Jordan, Susan D; Kuipers, David R, The Mispricing of Callable U.S. Treasury Bonds: A Closer Look, Journal of Futures Markets, vol. 18, no. 1, February 1998, pp. 35-51. __________________________________________________________________________________ Case 4. Portfolio Insurance: Leland O’Brien Rubinstein Associates Inc. SYNOPSIS: This case is aimed at helping you to understand the notion of portfolio insurance and how synthesized securities can improve risk-return profile a portfolio. Additionally, the case gives a great historical example of financial innovation, the challenges faced by technicians to find the right customers even when everything seems to work perfectly in theory. GENERAL OBJECTIVES: Differentiate between notions of “price” and “quantity” risk Understand how closely a put option and portfolio insurance are related. Describe why during the crash the portfolio insurance presumably didn’t work. Put things in perspective by understanding how the periphery, e.g., institutional arrangements, stock market structure, regulatory environment, and competitive conditions, affects prospect of even most stunningly great products. PERTINENT QUESTIONS: What is it about a typical insurance contract that doesn’t work? o i.e., why for security price risk hedging, one cannot rely on law of large numbers Why, despite the lure of the core idea, couldn’t Leland and Rubenstein sell their idea? o i.e., even though everybody likes less downside risk, only certain clienteles are interested in a particular risk-return profile How does portfolio insurance resemble a put option? o i.e., the right clienteles demand a return profile that is similar to that of the put option How can one reduce the cost of insurance? o i.e., replicate the put option dynamically without paying hefty option premiums When does the portfolio insurance work? o e.g., during a crash, large abnormal drops in prices, when markets halt, can the portfolio insurers effectively implement their strategies PORTFOLIO MANAGEMENT GAME: OBJECTIVE: The objective of this game is to give student a “real” feel of how fund management works. Since actively managed funds are mostly categorized by the size and growth characteristic of the stocks they select, we focus our attention to four major styles: large-growth, large-value, small-growth, and smallvalue. This is akin to the Morningstar® Style Box™ methodology (see Appendix). HOW TO BEGIN: Each student must first setup an account with Virtual Stock Exchange (see the course page for links). This allows us to track everyone’s performance throughout the semester. There are four different competition: large-growth stocks (ID: BADM744LG), large-value stocks (ID: BADM744LV), smallgrowth stocks (ID: BADM744SG), and small-growth stocks (ID: BADM744SV). Each of these portfolios should mimic the corresponding index in the Morningstar® Style Box™. To setup your fund and management firm officially, you need to file forms “ILUVMONY” and “IGOTFUND” with me no later than February 04, 2004. Each group must assign a managing director to represent the group. For each of the funds under your management, you have to file periodically forms “IGOTFUND” and “IDONTFUJ” by each reporting date. On the reporting date, each group must hold a press conference no longer than 10 minutes and explain their activities for the period. Enclosed, you may find a copy of these two forms. GUIDELINES: Each group must contain a total of at least 40 at most 80 stocks in their funds. Each fund should have at least 10 and at most 20 stocks. Each stock should have a minimum 5% and maximum 15% weight in your portfolio. You CANOT purchase bonds, short-sell stocks, invest in options or futures, or borrow funds. YOU ARE ALLOWED TO PURCHASE US STOCKS, ETFS (EXCHANGE TRADED FUNDS), ADRS (AMERICAN DEPOSITORY RECEIPTS), AND REITS (REAL ESTATE INVESTMENT TRUSTS). You may sell or buy at any time, but for every transaction a $10 fee will deducted from your portfolio. RULES OF CONDUCT: For every filing violation, including late filing, errors in documents, etc., you WILL BE FINED $2000 virtual money per occasion. For every substantive violation, such as overloading or underloading stocks, purchase or sale of prohibited securities, deliberate fudging of reports, etc., you WILL BE FINED $10000 virtual money per occasion. If the number of violation exceed 5 or the total fines surpasses $30000, you WILL BE ELIMINATED from the game and loose 10% of total grade point. EVALUATION: Upon completion of the game, all groups will be ranked based on their individual fund performances. The sum of ranking then determines final ranking of each group for each fund track. The finalist will be awarded 2½% for their efforts and other groups will be given pro rata grades for their performances. The overall grade is the sum of the group’s percentage scores for each fund track. Form “ILUVMONY” Fund Family Name: Fund Names: 1. Growth: _________________________________ 2. Value: ___________________________________ Managing Director: Managers: Name: Email: Name: Email: Name: Email: Name: Email: Name: Email: Form “IGOTFUND” Fund Name: Date: Holdings: Asset Symbol Shares Price Total Value Weight 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Total Signature and Seal of Management Team: Name: _______________________________ Sign: ___________________________________ Name: _______________________________ Sign: ___________________________________ Name: _______________________________ Sign: ___________________________________ Name: _______________________________ Sign: ___________________________________ Form “IDONTFUJ” Fund Name: Date: Transactions Log: Asset Date Symbol Buy / Sell Price Shares Total Value 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Signature and Seal of Management Team: Name: _______________________________ Sign: ___________________________________ Name: _______________________________ Sign: ___________________________________ Name: _______________________________ Sign: ___________________________________ Name: _______________________________ Sign: ___________________________________ Here's a question that pops up from time to time on our Socialize boards: "According to its style-box diagram, my fund is a large-cap blend offering, but Morningstar includes it in the large-cap growth category. Which one is right?" Actually, they're both correct. Here's why: The Morningstar style box is a snapshot that tells you the characteristics of a fund's current portfolio. Morningstar categories are analogous to the style box, but they are based on how a fund has invested over the past three years, not just its most recent portfolio. The two are often the same, but sometimes they are different. The Morningstar style box was a result of our efforts to devise a more meaningful way to describe the "investment style" of mutual funds. As Morningstar president Don Phillips noted at the time, discussing mutual funds can be perplexing. There are growth funds, aggressive-growth funds, value funds, as well as funds that focus on companies from a particular sector or companies of a certain size. (And that's just on the stock side.) The problem with these prospectus-based descriptions of investment style is that frequently they are too broad to provide investors with much useful information about the way a fund invests its assets. Further, even if a particular fund describes itself accurately, no two fund companies are likely to have the same definition of "value" or "small-cap." One way to resolve this dilemma is to look beyond how funds describe themselves and examine what the fund actually owns--their underlying portfolios. In the past, "style boxes" based on a portfolio's size and investment characteristics were devised for portfolios of stocks. If you think of the equity universe as a cake in a pan, these boxes used two cuts to divide the cake into four pieces: This four-box matrix is useful, but it falls short of our needs. With only two choices for each dimension, such a matrix results in groupings that contain a great deal of variation. Four segments simply aren't sufficient to divide the equity market into meaningful groups. Morningstar refined this box by adding two more "cuts" to produce a box with nine segments, with the vertical divisions based on the size of companies in the fund's portfolio, and the horizontal divisions made according to the portfolio's valuation ratios relative to a market benchmark: Here's how we place a fund within the style box: Market capitalization is fairly easy is to determine. The market capitalization of a stock is equal to the number of shares outstanding multiplied by the current price of the stock. For a portfolio of stocks, the "median market cap" is often used to describe the size of companies in the portfolio. To determine the "median" company, you can rank the companies from largest to smallest, and then pick the one in the middle. There is, however, a potential drawback to this method. For example, if a fund held a large number of relatively small positions in companies at either end of the scale, these companies could "distort" the median market cap. Such a median market cap might not accurately reflect the fund's true investment style. For this reason, Morningstar uses an alternate method for determining the median market cap of a portfolio. We rank the companies in a portfolio from largest to smallest, and move down the list until we reach the point at which half of the fund's assets are invested in larger companies and the remainder is invested in smaller companies. Setting the boundaries for investment style--the horizontal axis--is a bit more complicated. Two commonly used methods to measure value (or lack thereof) are price/earnings ratios and price/book ratios. However, if you group funds according to these ratios, you often get vastly different results. One fund might have a "growth" strategy according to its P/E ratio, while its P/B ratio might point to a value investment strategy. So instead of choosing between one or the other, we made the decision to use both. And, because of continuous change in the market, we use relative ratios. For example, based on the long-term averages of the stock market, a P/E ratio of 25 is somewhat high, but in comparison with the current market, it's actually less than that of broad market indexes. To determine a fund's investment style we divide its current P/E ratio by that of the S&P 500 and divide its current P/B by that of the same benchmark. We then add those two numbers together. If the resulting sum is less than 1.75, we consider the fund to have a value investment style. If the sum is more than 2.25, we consider the fund to have a growth investment style. Anything between 1.75 and 2.25 is considered a "blend" style. Here's how it works: Currently, the Oakmark fund has a median market cap of $14.7 billion, which places it in the top row of our style box. And, based on its most-recent portfolio, it has a P/E ratio of 25.6 and a P/B ratio of 4.3. If we divide the fund's P/E ratio by that of the S&P 500, we get 0.91. Its P/B ratio relative to the index is 0.64. If we add them together, we get 1.55, which represents a value investment style: We also produce a style box for fixed-income funds. Instead of market cap and valuation levels, though, credit quality and interest-rate sensitivity are used to assign bond portfolios to one of nine segments. We introduced our style box in 1992, but we continued to categorize funds by their prospectus-stated investment objectives. However, in 1995, we made the decision to replace the old prospectus-based investment objectives with investment categories based on the way funds actually invest. For domestic stock funds, these categories corresponded with the nine segments of our style box. Assigning funds to these categories, though, is a bit more involved than using a fund's style box to determine its category. That's because funds don't always land in the same area of the style box. A fund that is “mid-cap growth” according to its current portfolio might be a large-cap growth fund with its next portfolio. Our definitions are not arbitrary, but they are artificial, and some funds will not consistently land in the same square with each of their portfolios. For some funds, this is the result of changes in investment style, while for others, normal fluctuations in their portfolio are enough to bump the fund into a different segment of the style box. For these reasons, funds are assigned to categories based on their style boxes over the past three years. Once a category is assigned, a change in one subsequent portfolio alone will not cause us to move it, but if the fund consistently shows up in a different area of the style box, we will move it to the respective category. So are all of our efforts worth it? The answer is a qualified yes. There is still variation within any segment in the style box, but our style-based fund categories produce groupings of funds that have more in common with each other than did the funds within the old prospectus-based investment objectives. Moreover, some very clear risk and return patterns emerge when we look at the long-term performance of funds by their style-box location. On average, funds in the three upper-left-hand segments of the box have the mildest risk scores, funds in the center row have somewhat higher risk scores, and the funds in the three lower-right-hand segments of the box have by far the highest risk scores. The style box doesn't tell the whole story, but when cooking up a portfolio, it's a good place to start. The style box can help you size up the investment style of a fund, its risk and return potential, and how it fits with the other funds in your portfolio. Posted: 03-13-98 David Harrell is an editorial analyst for Morningstar.com. He can be reached at dharrel@morningstar.net.