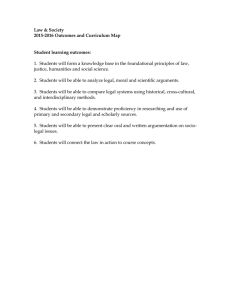

LAW & SOCIETY Orienting Perspectives on Law & Society ...[A

advertisement

LAW & SOCIETY Orienting Perspectives on Law & Society ...[A] primary problem of all legal studies may be the intersecting of law and the other institutions of society. This relationship is no mere reflection of society in the law: it must be realized, rather, that the law is always out of phase with society, specifically because of the duality of the statement and restatement of rights. Indeed, the more highly developed the legal institutions, the greater the lack of phase, which not only results from the constant reorientation of the primary institutions but is magnified by the very dynamics of the legal institutions themselves. Bohannon 1968: 73-78. Sociolegal Studies vs. Sociology of Law Campbell and Wiles 1976: 547-555 Sociolegal studies deal "with the actual operation of law and its effects on people--with access to legal services, with the treatment afforded to defendants in court, with welfare and poverty issues. ... [A] concern about 'justice' ... runs as a leitmotif through sociolegal studies. ... [Sociolegal] research is largely descriptive, it focuses on particular legal agencies or discrete legal institutions... Given the interest in justice, in reform and the improvement of the legal system, social science methods are seen as useful in precisely identifying the optimum means to achieve the ends in view. ... [T]he hegemony of law [that it can be effective in reform] is accepted... [T]he nature of the legal order is treated as unproblematic, especially in its relationship to the rest of the social world. ... Research is unambiguously utilitarian, and pragmatic in orientation, and the suggestions for reform which flow from it tend to be limited in scope and of a legalistic nature." In Sociology of Law, the "focus in ... on understanding the nature of social order through a study of law. Insofar as law is scrutinized it is from a perspective that attempts to be exogenous to the existing legal system. The goal is not primarily to improve the legal system, but rather to construct a theoretical understanding of that legal system in terms of the wider social structure. The law, legal prescriptions and legal definitions are not assumed or accepted, but their emergence, articulation and purpose are themselves treated as problematic... Reform of the legal system is not, as such, the goal even though an adequate theory of law may entail a consideration of the relationship of law to social change." Orienting Perspectives Jurisprudence vs. Sociology of Law Milovanovic 1994: 1-5 Jurisprudence is the study of: 1) the existing system of written rules, established in codified form by the state (statutory and case law); 2) their ongoing systematization into a body of relevant law by some coordinating principle of justification; 3) the application of doctrinal legal discourse that is structured by a relevant morphological structure (word meanings) and syntactical structure (linear constructions of narratives and texts) in doing 'correct' reasoning in law; 4) the formal, logical application of abstract and general legal propositions and doctrines by the use of doctrinal legal discourse to 'factual' situations by a specialized staff which provides a high degree of probability of resolution of the issue(s) in controversy; and 5) how all conflicts can be inevitably subsumable (selfreferencing) to some absolute postulates which provide the body of core premises and criteria for the correct resolution of differences in a self-regulating (homeostatic) formal system. Sociology of law, on the other hand, is the study of: 1) the evolution, stabilization, function, and justification of forms of social control; 2) the forms of legal thought and reasoning as they relate to a particular political economic order [why limit this to economics?]; 3) the legitimation principles and the effects that evolve with them; 4) the 'causes' of the development of the form of social control and staff of specialists that are its promoters; 5) the transmission of 'correct' methods of legal reasoning; 6) the creation of the juridic subject with formal, abstract and universal rights; 7) the evolution of the juridico-linguistic coordinate system (legal discourse) [and we accuse lawyers of self-serving jargon] in use and its nexus with the political economic sphere [again why limit it to political and economic?]; and 8) the degree of freedom or coercion existing in the form of law. Orienting Definitions of Law "[T]he prophecies of what the courts will do in fact, and nothing more pretentious, are what I mean by the law." Holmes 1897: 461. "A principle or rule of conduct so established as to justify a prediction with reasonable certainty that it will be enforced by the courts if its authority is challenged is, then for the purposes of our study, a principle or rule of law." Cardozo 1921: 52. Law is the "union of primary and secondary rules." "Under rules of the one type, which may well be considered the basic or primary type, human beings are required to do or abstain from certain actions, whether they wish to or not. [Secondary rules] provide that human beings may by doing or saying certain things introduce new rules of the primary type, extinguish or modify old ones, or in various ways determine their incidence or control their operation." Hart 1961: 77-79. Law is "'a body of binding obligations regarded as right by one party and acknowledged as the duty by the other' which has been reinstitutionalized within the legal institution so that society can continue to function in an orderly manner on the basis of rules so maintained." ...[T]wo aspects of legal systems are not shared with other institutions of society. First, legal institutions alone must have some recognized way to interfere in the malfunctioning ... of the nonlegal institutions... Second, there must be two kinds of rules in the legal institutions, [procedural and substantive]. ... Legal rights have their material origins in the customs of nonlegal institutions but must be overtly restated for the specific purpose of enabling the legal institutions to perform their tasks [which changes the nature of the rights and places the law out of phase with other institutions]. Bohanan 1968:73-78. "A social norm is law if its breach is met by physical force or the threat of physical force in a socially approved and regular way by a socially authorized third person." Akers 1965: 306. "Law is governmental social control." Black 1976:2. "Sociologically, law consists of the behaviors, situations, and conditions for making, interpreting, and applying legal rules that are backed by the state's legitimate coercive apparatus for enforcement." Vago 1997:9. According to Gibbs's (1967: 431) composite definition, law includes the following elements: 1) an evaluation of conduct held by at least one person in a social unit, and 2) a high probability that, on their own initiative or at the request of others, persons in a special status will attempt by coercive or non-coercive means to revenge, rectify, or prevent behavior that is contrary to the evaluation, with 3) a low probability of retaliation by persons other than the individual or individuals at whom the reaction is directed. Law is "social control through legitimized coercion." Akers and Hawkins 1975:8. "[I]n our introduction to sociology of law we merely wish to indicate the varying positions on the law. ... [T]he accepted definition of law dictates the scope of the analysis of law." Milovanovic 1994: 8. Characteristics of Modern Law (Galanter 1966) 1. Uniformity of rules and their applications. Law recognizes only functional differences among people (e.g., ability), not intrinsic differences (age, gender, race). In other words, achieved rather than ascribed statuses are stressed. 2. Transactional basis for rights and duties. Obligations arise from our agreements and interactions, not from unchanging obligations based on personal or group identity. 3. Universalism. Legal decisions apply to all similar cases are do not vary from case to case. 4. Hierarchical administrative system. Downward vertical lines of authority dominate; upward appeals must go through proper channels. 5. Bureaucracy. Use of impersonal procedures and written rules and records to that decision depend on more objective application of rules and not the personal whims or decisionmakers. 6. Rationality. Modern law is constituted by understandable rules which are designed to achieve clearly stated goals by using methods that can be demonstrated to work. 7. Professionals. The system is operated by people who have qualifications (e.g., police, judges, administrative hearing officers). 8. Lawyers. An occupational group with special training acts as go-betweens to work for clients in their dealing with the system. 9. Changeability. can be made. Rules and procedures exist by which changes 10. Politicality. Modern law serves the purposes of the state/government (as opposed to other social institutions like the family, church, education, economy). 11. Separation of powers. Legislative, judicial, and executive functions are separated and distinct in modern law. Views on the Functions of Law "[S]ocial control [is] the defining characteristic (dispute settlement can be subsumed under social control)..." Akers and Hawkins 1975: 8. (See also the social control emphasis in the definitions of law offered by Black and Gibbs.) Friedman (1984: 8-14) lists four basic functions: social control, dispute settlement, social engineering (planned social changed imposed from the top), and social maintenance. Milovanovic (1994: 8-14) lists three basic kinds of functions: repressive functions (coercion), facilitative functions (certainty and predictability in behavior), and ideological functions including domination, legitimation, hegemony, and reification (a process which establishes some relative independent existence to constructed orders). Vago (1997: 6-18) discusses both functions (social control, dispute settlement, and social change) as well as dysfunctions (conservative tendencies, rigidity due to formality in law works against its effectiveness in problem-solving, normative overcontrol, and legal categories themselves become forms of discrimination). Glossary Refresher of Basic Sociology Concepts From John E. Conklin, (1984) Sociology: An Introduction. York: Macmillan. New Social Structure: Interaction among people that recurs ina regular and stable pattern over time; the form or shape of social relatiponships. Status: A position within a social structure. Ascribed Status: A social position assigned to a person by others... Achieved Status: A social position that a person acquires by choice, effort, or merit. Role: The behavior expected of a person who occupies a particular status. Role Set: The various roles attached to a single status. [We also need to establish terminology to refer to the combination of statuses and roles individuals have, perhaps a role composite.] Role Conflict: [The existence of] [a]n incompatibility between two or more roles that a person is expected to play. [May or may not be subjectively appreciated.] Role Strain: [The existence of] incompatibility in the expectations of a single role ... [May or may not be subjectively appreciated.] Master Status: Themost important status in a person's life, the one that determines his or her social identity. Reference Group: A group or category that people use to evaluate themselves and their behavior [or perhaps others use to evaluate a person or her/his behavior]. Institutionalization: The process by which institutions are created. Institution: A stable cluster of values, norms, statuses, and roles that enjoys wide support in a society. Value: An abstract and shared idea about what is desirable, good, or correct. Norm: A rule or expectation about appropriate behavior for a particular person in a specific situation.