Julia1 - Mighealth.net

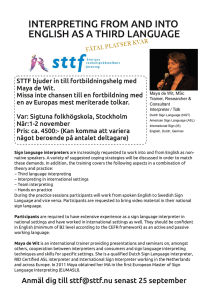

advertisement

Effectiveness and CC training, interpretation: some recent articles Development and evaluation of a cultural competency training curriculum David H Thom1 , Miguel D Tirado2 , Tommy L Woon3 and Melen R McBride4 FULL TEXT: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6920/6/38 Notes from the Discussion and Conclusion sections: Discussion No measurable impact of a brief (4.5 hours) training curriculum aimed at improving physician cross-cultural knowledge and skills on any of the outcomes we chose. Other cultural competency studies have shown positive training effects on physician knowledge, attitudes and skills (by physician self-report) [11,12], no previous study has apparently reported changes in patientcentered outcomes and disease-specific outcomes measured over a period of 6 months. Not surprising: more studies showing effect used more extensive training – but modest and not persistent Typical CME have been shown to have limited utility in effecting changes in physician behaviors [24,25]. May require a combination of interactive training, dedicated practice time, and reinforcement of behavioral changes in the practice environment. A recent systematic review of the methodological quality of studies evaluating cultural competence training of health professionals [12] concluded that "most did not adhere to basic principles of study design, reporting and data analysis." Of 64 studies evaluated "only eight had adequate comparison groups." Conclusion Hard to get from CCT to health outcomes, must connect training to changes in behavior, and changes in behavior to improved patient outcomes. Our primary goal in the current study, to effect a significant measurable change in patient-perceived physician behaviors, was not achieved. It is likely that a stronger intervention – with a longer period of training and practice time and regular reinforcement over time – is needed to effect a measurable behavioral change. Effecting changes via physician training on patient trust, satisfaction, or 'hard' disease-specific outcomes is an even higher bar to reach. Beach MC, Price EG, Gary TL, Robinson KA, Gozu A, Palacio A, Smarth C, Jenckes MW, Feuerstein C, Bass EB, Powe NR, Cooper LA: Cultural Competence: a systematic review of health care provider educational interventions. Med Care 2005, 43(4):356-73. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text OBJECTIVE: We sought to synthesize the findings of studies evaluating interventions to improve the cultural competence of health professionals. DESIGN: This was a systematic literature review and analysis. METHODS: We performed electronic and hand searches from 1980 through June 2003 to identify studies that evaluated interventions designed to improve the cultural competence of health professionals. We abstracted and synthesized data from studies that had both a beforeand an after-intervention evaluation or had a control group for comparison and graded the strength of the evidence as excellent, good, fair, or poor using predetermined criteria. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES: We sought evidence of the effectiveness and costs of cultural competence training of health professionals. RESULTS: Thirty-four studies were included in our review. There is excellent evidence that cultural competence training improves the knowledge of health professionals (17 of 19 studies demonstrated a beneficial effect), and good evidence that cultural competence training improves the attitudes and skills of health professionals (21 of 25 studies evaluating attitudes demonstrated a beneficial effect and 14 of 14 studies evaluating skills demonstrated a beneficial effect). There is good evidence that cultural competence training impacts patient satisfaction (3 of 3 studies demonstrated a beneficial effect), poor evidence that cultural competence training impacts patient adherence (although the one study designed to do this demonstrated a beneficial effect), and no studies that have evaluated patient health status outcomes. There is poor evidence to determine the costs of cultural competence training (5 studies included incomplete estimates of costs). CONCLUSIONS: Cultural competence training shows promise as a strategy for improving the knowledge, attitudes, and skills of health professionals. However, evidence that it improves patient adherence to therapy, health outcomes, and equity of services across racial and ethnic groups is lacking. Future research should focus on these outcomes and should determine which teaching methods and content are most effective. J Gen Intern Med. 2007 November; 22(Suppl 2): 312–318. PMCID: PMC2078551 Published online 2007 October 24. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0360-8. Copyright © Society of General Internal Medicine 2007 Patient Satisfaction with Different Interpreting Methods: A Randomized Controlled Trial Francesca Gany, M.D., M.S., 1 Jennifer Leng, M.D., M.P.H.,1 Ephraim Shapiro, M.B.A., M.P.A.,1 David Abramson, Ph.D., M.P.H.,2 Ivette Motola, M.D., M.P.H.,3 David C. Shield,4 and Jyotsna Changrani, M.D., M.P.H.1 With the large growth of the foreign-born population in the United States, the study of interpreting strategies outcomes for language-discordant encounters is of great importance. The introduction of RSMI, with its potential for more efficient interpreting because of its simultaneity, compelled studying its impact in relation to U&C interpreting. In this randomized controlled trial of RSMI vs. U&C interpreting, there were a few areas in which patients in the RSMI group were more satisfied than in the U&C group. Patients felt they were treated with more respect by their physicians and that their privacy was better protected. The exposure analysis revealed similar outcomes. Exposure analysis results are relevant, as patients usually did not receive the randomized method because of language concordance with their physicians, not because of interpreting method preference. Alarmingly, all groups reported poor satisfaction with important aspects of doctor–patient communication, in particular, feeling understood by the physician, understanding physicians’ explanations of procedures and results, and understanding instructions for follow-up care. However, this was much worse for patients in the interpreted medical encounter, indicating that current interpreting strategies still do not approximate a language-concordant encounter. Among language-concordant patients, dissatisfaction may have been due in part to physician “false fluency”, with physicians overestimating their language abilities; to patients’ overestimating their English-speaking ability; or to other shortcomings in doctor–patient communication. In a separate study, we found a significantly lower error rate with RSMI compared with U&C interpreting in Spanish–English language-discordant encounters.32 However, comprehension was still perceived to be poor in our study, suggesting that technical accuracy alone is not sufficient. More studies are needed encompassing other languages and settings to further assess accuracy, efficiency, and patient satisfaction with the different methods of interpretation. Patient satisfaction in cross-cultural patient–physician interactions is likely related to a constellation of factors, including socioeconomics, culture, race and ethnicity, time, and the logistics and quality of the interpreting method. In previous studies, satisfaction has been shown to have a positive impact on clinical outcomes.17–20 The results of this study, therefore, have important implications. RSMI may be particularly useful in clinical situations where sensitive topics are discussed and patient privacy is paramount. The mental health encounter, the discussion of sexual behavior, and the evaluation of sexually transmitted diseases, for example, require a high level of patient comfort with their providers and assurance of privacy.33,34 The absence of a third party from the actual exam room during an RSMI (or RCMI) encounter may remove one potential barrier to patients’ willingness to disclose sensitive information. Our findings suggest that RSMI could be an important component of a multipronged approach to improving patient satisfaction in the interpreted encounter, but also that much more work needs to be done. Professional interpreters, physicians, and patients need more training and education on how best to facilitate the interpreted medical encounter. Further studies need to be conducted on interpreting modalities, and should examine errors, medical outcomes, and costs. Physician-related factors should also be assessed, including physician satisfaction and barriers to utilization. We also need qualitative data to learn more about what specifically detracts from patient satisfaction with interpreting so that appropriate interventions can be developed to address the dissatisfaction documented in this study. Future studies should include additional technology-based interpreting delivery systems, including video and computer-assisted linguistic access. The Impact of Medical Interpretation Method on Time and Errors Francesca Gany, MD, MS,5 Luciano Kapelusznik, MD,5 Kavitha Prakash, MD, MPH,2,3 Javier Gonzalez,5 Lurmag Y. Orta, MD,4 Chi-Hong Tseng, PhD,1 and Jyotsna Changrani, MD, MPH5 Corresponding author: Francesca Gany, Phone: +1-212-2638897, Fax: +1-212-2638234, Email: fg12@nyu.edu. Background Twenty-two million Americans have limited English proficiency. Interpreting for limited English proficient patients is intended to enhance communication and delivery of quality medical care. Objective Little is known about the impact of various interpreting methods on interpreting speed and errors. This investigation addresses this important gap. Design Four scripted clinical encounters were used to enable the comparison of equivalent clinical content. These scripts were run across four interpreting methods, including remote simultaneous, remote consecutive, proximate consecutive, and proximate ad hoc interpreting. The first 3 methods utilized professional, trained interpreters, whereas the ad hoc method utilized untrained staff. Measurements Audiotaped transcripts of the encounters were coded, using a prespecified algorithm to determine medical error and linguistic error, by coders blinded to the interpreting method. Encounters were also timed. Results Remote simultaneous medical interpreting (RSMI) encounters averaged 12.72 vs 18.24 minutes for the next fastest mode (proximate ad hoc) (p=0.002). There were 12 times more medical errors of moderate or greater clinical significance among utterances in non-RSMI encounters compared to RSMI encounters (p=0.0002). Conclusions Whereas limited by the small number of interpreters involved, our study found that RSMI resulted in fewer medical errors and was faster than non-RSMI methods of interpreting. The Impact of an Enhanced Interpreter Service Intervention on Hospital Costs and Patient Satisfaction Elizabeth A. Jacobs, MD, MPP,1,2 Laura S. Sadowski, MD, MPH,1,2 and Paul J. Rathouz, PhD3 J Gen Intern Med. 2007 November; 22(Suppl 2): 319–323. Published online 2007 October 24. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0361-7. PMCID: PMC2078536 Corresponding author: Elizabeth A. Jacobs, Phone: +1-312-8647311, Fax: +1-312-8649694, Email: ejacobs@rush.edu. BACKGROUND Many health care providers do not provide adequate language access services for their patients who are limited English-speaking because they view the costs of these services as prohibitive. However, little is known about the costs they might bear because of unaddressed language barriers or the costs of providing language access services. OBJECTIVE To investigate how language barriers and the provision of enhanced interpreter services impact the costs of a hospital stay. DESIGN Prospective intervention study. SETTING Public hospital inpatient medicine service. PARTICIPANTS Three hundred twenty-three adult inpatients: 124 Spanish-speakers whose physicians had access to the enhanced interpreter intervention, 99 Spanish-speakers whose physicians only had access to usual interpreter services, and 100 English-speakers matched to Spanish-speaking participants on age, gender, and admission firm. MEASUREMENTS Patient satisfaction, hospital length of stay, number of inpatient consultations and radiology tests conducted in the hospital, adherence with follow-up appointments, use of emergency department (ED) services and hospitalizations in the 3 months after discharge, and the costs associated with provision of the intervention and any resulting change in health care utilization. RESULTS The enhanced interpreter service intervention did not significantly impact any of the measured outcomes or their associated costs. The cost of the enhanced interpreter service was $234 per Spanish-speaking intervention patient and represented 1.5% of the average hospital cost. Having a Spanish-speaking attending physician significantly increased Spanish-speaking patient satisfaction with physician, overall hospital experience, and reduced ED visits, thereby reducing costs by $92 per Spanish-speaking patient over the study period. CONCLUSION The enhanced interpreter service intervention did not significantly increase or decrease hospital costs. Physician–patient language concordance reduced return ED visit and costs. Health care providers need to examine all the cost implications of different language access services before they deem them too costly. See also the complete supplemental issue of Journal of General Internal Medicine Volume 22, Supplement 2 / November, 2007 Language Barriers in Heath Care http://www.springerlink.com/content/t744v8u05t62/?p=9f63f10c2a1443f1ae6ff5232ed3a316&pi=30