Impact Studies of EQM in Higher Education

advertisement

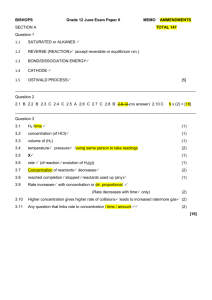

Trance, Transparency and Transformation The impact of external quality monitoring on higher education Keynote presentation at the Seventh Quality in Higher Education International Seminar Melbourne, 29-31 October 2002 Bjørn Stensaker NIFU (Norwegian Institute for Studies in Higher Education) Hegdehaugsvn. 31 0855 Oslo bjorn.stensaker@nifu.no 1 Trance, Transparency and Transformation The impact of external quality monitoring on higher education Abstract The paper discusses the impact of external quality monitoring (EQM) on higher education, and identifies areas in higher education where changes have taken place as a result of such external initiatives. Of special interest is the question whether quality improvement actually is the result of the many EQM systems implemented. By interpreting available data an ambiguous answer is provided, highlighting some of the typical side effects of current EQM systems at the institutional level. The paper argues that lack of effects directly related to quality improvement should not be conceived as an EQM design error alone but as a misconception of how organisational change actually takes place. In the conclusion, it is claimed that a more dynamic view on how organisations change, highlighting the responsibility of the institutional leadership as ‘translators of meaning’ may contribute to a more useful process. Introduction External quality monitoring (EQM) has been one of the most characteristic trends in higher education in the last 10 to 15 years. In almost all OECD-countries, and expanding to other countries as well, EQM has been introduced either a result of indirect government pressure (for example, the Netherlands) or as a result of a direct governmental initiative (for example, France and the UK) to change the steering of and/or renew the higher education sector (Neave 1988; Westerheijden, Brennan & Maassen 1994; Kogan et al. 2000). The governmental interest in EQM has many facets, and is linked in various ways to a range of other policy and reform initiatives in higher education. This fact is reflected when looking into the purposes and objectives of EQM. Empirical research by Frazer (1997) and Brennan & Shah (2000:, p. 31–2) has shown that EQM systems seem to have many uses: to ensure accountability for the use of public funds; to improve the quality of higher education provision; to inform students and employers; to stimulate competitiveness within and between institutions; to undertake a quality check on new (and often private and for-profit) institutions; to assign institutional status as a response to increased diversity within higher education; to support the transfer of authority between the state and institutions; to assist mobility of students; to make international comparisons, due to increasing mobility of students and staff. 2 Apart from many national initiatives in the EQM area, a striking tendency during the 1990s has also been the growing interest in international co-operation and in international studies focusing on EQM. These initiatives are important in the sense that they provide rich and comparable data on the what, how and why of the many EQM initiatives taken. In addition, they also provide a mechanism by which policy and practise is spread across national borders (Brennan, de Vries & Williams 1997, p. 171). At present, a range of such international initiatives and networks exist, from more global ones such as the International Network of Quality Assurance Agencies in Higher Education (INQAAHE) and regional networks like the European Network for Quality Assurance Agencies (ENQA), to more informal networks like the annual meeting of the Nordic quality assurance agencies in higher education. In addition, more specialised networks such as the European Foundation for Management Development (EFDM) in business education has launched their own quality reviews (EQUIS). Partly as a result of such networks some common practises as to how EQM is designed and organised seems to have been spread to a number of countries. Thus, four elements are usually identified when characterising EQM procedures (van Vught & Westerheijden 1994): a national co-ordinating body that administer the evaluations conducted, an institutional selfevaluation phase, an external evaluation, and the production of a report. The apparent similarities between these initiatives have led observers to suggest that, at least in a European context, a general model of quality assurance has evolved (van Vught & Westerheijden, 1994). However, as Brennan (1999, p. 221) has noticed, this so-called general model of quality assessments obscures as much as it reveals about what is going on in these processes. Not least is the political context, the power distribution in different higher education systems, methodological differences and intended outcomes of the evaluation processes, important sources of differentiation in the various systems (Kells, 1999; Neave, 1996). Looking back at the development of methods and types of evaluations conducted in the last decade, there also seems to be a tendency of an ongoing ‘inflation’ of EQM. For example, while audit systems with a focus on the institutional level was the dominant theme in Sweden during the 1990s, the country has, during the latter years, expanded its EQM scheme to include more disciplinary and programme evaluations. In Denmark, a country known for its comprehensive disciplinary and programme scheme, the intentions is that these processes should be supplemented by faculty and/or institutional evaluations in the future. In other words, while new methods and types of EQM are introduced, older versions of EQM are not abandoned. At the European level, there is at present also much interest in developing some sort of supranational accreditation arrangement — external evaluations that could promote further internationalisation and mutual recognition of degrees and programmes across national borders (Westerheijden, 2001). In addition to the fact that this development may add to the growing internationalisation of EQM, it also relates to the former point in that accreditation procedures are added to existing EQM schemes without eliminating already-implemented methods. 3 The growing number of methods and types of EQM used, the increasing internationalisation of EQM and the variety of purposes associated with EQM suggest that studying the impact of EQM should be given increased attention. The popularity and the many uses of EQM internationally can be an indication of a successful and adequate procedure but that should not be taken for granted. In other words, there is a need for a critical review of what the impact of EQM is on higher education. This paper will discuss some of the consequences of the introduction of EQM in higher education by: reviewing some of the studies that has addressed the impact issue; providing some interpretations of the research findings on EQM impact highlighting the complexity and ambiguity of the findings; discussing whether quality improvement actually is the outcome; arguing that current EQM systems are based on a somewhat mechanistic view of policy implementation and organisational change and that there is a need for a more dynamic view of the roles and responsibilities of the actors involved in the EQM process. Impact Studies of EQM in Higher Education Measurement problems There are obvious methodological problems attached to studying the effects of the many EQM initiatives in higher education. How do we know that a certain external initiative is causing experienced internal effects (Hackman & Wageman, 1995)? Quality work and evaluations of quality are only some of the many external and internal processes and reform measures that higher education institutions continuously handle and react upon. Isolating the effects of a particular process is, therefore, difficult. Measuring impact is further complicated due to universities’ and colleges’ complex forms of information-processing and decisionmaking traditions (Weusthof, 1995; Brennan, 1997; Askling, 1997). A particular problem when analysing effects relates to the many purposes associated with EQM. Since EQM has many potential uses, a semantic problem occurs: one risks the possibility of relating change to EQM when in reality, the experienced change is implemented due to other administrative or organisational measures. Thus, perhaps it is not surprising that research has shown that ‘quality’ is the most important factor affecting organisational performance in general (Reeves & Bednar, 1994, p. 419). Another methodological problem is related to the potential political and economic gains of being a ‘good implementer’ of EQM. An empirical example may illustrate the point. In a study of organisations adopting Total Quality Management systems (TQM), Zbaracki (1998) 4 claims that due to managers and other stakeholders’ interest in developing a successful image of their own efforts, the impact of TQM is often measured overly optimistically. There is a danger that similar tendencies also relate to studies of the impact of EQM. EQM and the impact on teaching and learning Early studies from the Netherlands found quite positive effects of EQM for teaching and learning at higher education institutions. Not least it was argued that a ‘sound self-evaluation under full faculty responsibility, offered the best guarantee for quality maintenance and improvement’ (Weusthof 1995: 247). Moreover, studies also showed that about half of the recommendations given to institutions by the visiting committees after evaluations were followed up as intended. However, Frederiks et al. (1994, p. 196) concluded, after empirical testing of some hypothesis on follow-up of assessments conducted in the Netherlands, that it was difficult to find a specific factor leading to follow-up of external assessments. Still, their main conclusion was that increased attention towards the quality of teaching as a result of the external assessments could be identified. A finding echoed by studies conducted in other countries (Jordell, Karlsen & Stensaker, 1994; Saarinen, 1995; Brennan, Frederiks & Shah, 1997). Other studies have indicated a related set of effects in higher education institutions as a consequence of various national EQM systems. Dill (2000), studying the outcomes of academic audit procedures in the UK, New Zealand, Hong Kong and Sweden, listed several effects of these procedures: increased institutional attention towards teaching and learning, more active discussions and co-operation within academic units, a more clarified responsibility for improving teaching and student learning and provision of better information on best practice. Massy (1999), in a study of quality audit procedures in Sweden and Denmark, stated that these evaluations had created a serious discourse on quality issues. He maintained that the way the quality concept was implemented in the two countries created an atmosphere of trust and an openness triggering learning both by institutions and by the intermediate bodies initiating the evaluation procedures. Still, he remained open to the question whether external evaluations actually had led to a better ‘product’ when it comes to teaching and learning. An international survey of what measures academics thought had most impact on teaching quality also showed that various forms of evaluations focusing on teaching and review of courses was not seen as very relevant (Wright, 1995). Some EQM systems linked to teaching and learning have also been linked with more market inspired funding and resource allocation models, especially in several Anglo-American countries. According to one observer this have had ‘major effects on the lives of English academics’ (Kogan et al. 2000, p. 187). Thus, some external assessment exercises in the UK have been found to establish an institutional compliance culture to these requirements (Kogan et al. 2000, p. 188; Henkel, 2000, p. 262, see also Harvey, 1995). A hardly surprising finding 5 given that academics scrutinised by these assessments often reported that they felt like being ‘inspected’ (Brennan, Frederiks & Shah ,1997, p.74). Thus, the impact of EQM of teaching and learning seems indeed to be quite mixed. EQM and the impact on organisation and academic leadership EQM systems are not only concerned with teaching and learning. Some are more concerned with organisational requirements surrounding the education, and are using an indirect method for evaluating or improving quality. Brennan (1999, p.231), drawing on both a study of effects on quality assessments in the UK (Brennan, Frederiks & Shah 1997) and an OECD study investigating impacts of quality assessment procedures in institutional governance and management structures (Shah, 1997; Brennan & Shah, 2000), argues that EQM has effects other than raising the profile of teaching and learning in higher education institutions. Not least these studies have found that EQM may have an impact on organisation and management issues. More centralisation in procedures and in organisational decision-making is one trend. A more autonomous role for the institutional management, including giving managers greater responsibility for taking actions to follow up external evaluations is another trend. Other observers have noted similar changes in organisation and management as a consequence of various EQM schemes. In several countries, studies have concluded that a greater centralisation in higher education institutions seem to be a rather common result of external evaluations (Stensaker, 1996; Askling, 1997; Stensaker, 1999a, 1999b). Not least, various forms of EQM seem to have raised institutional awareness when it comes to strategic questions (Askling, 1997, p. 24). As a side-effect, institutions put more effort in their external image where they try to make their output more impressing and ‘visible’ (Stensaker, 1996). A much-related effect of increasing centralisation is the tendency noted that higher education institutions have become more ‘bureaucratic’. One study from Norway (Gornitzka et al., 1996) shows that, for example, university administration is changing its profile and functioning where simple tasks and positions are removed and replaced by administrators performing more complex and strategic tasks. Even if it can be argued that this trend is not caused by EQM systems alone, a large comparative study of change processes in higher education in the UK, Sweden and Norway during the 1990s, found that EQM is an important contributor to increased ‘bureaucratisation’ (Kogan et al., 2000). Linked with the bureaucratisation issue is also the question whether the EQM system is an efficient instrument for checking and improving higher education. In economic terms this is a little researched topic. However, studies have indicated that as much as 10 percent of educational programme cost in the US could be related to various kinds of evaluation processes (Alkin & Stecher 1983). A recent study from England estimate that EQM costs higher education institutions between 45–50 million pound in attributed administrative and academic time, approximately 100 million pound when it comes to information gathering and processing, and an additional 100 million pound of so-called unmeasured costs (unattributed 6 staff time and non-staff costs) (PA Consulting,2000). The conclusion that followed stated that EQM schemes in England was a ‘patchwork of legacy requirements from different stakeholders responding to different concerns at different times, with little overarching design, co-ordination or rationale. In consequence, the current régime represents poor value for money both for stakeholders and for institutions’ (PA Consulting, 2000, p. 7). Has quality been improved? The studies reviewed do not provide the reader with the full picture of the many effects related to EQM, not least since differences in various countries are downplayed in the analysis. Thus, the review should rather be seen as an attempt to draw up some general tendencies when it comes to the impact of EQM in higher education, tendencies that display a rather mixed picture. Even if positive claims are made that EQM trigger, for example, increased attention towards teaching and learning and signs of a cultural change in the attitudes of the academic staff, other studies show that EQM also contributes to more ambiguous or even negative outcomes, for example, that money spent on EQM outweighs the potential benefits for institutions (and for the system as a whole), and that various evaluations and monitoring systems trigger greater centralisation and more ‘bureaucratisation’ in higher education institutions. Related to the latter tendencies it can be claimed that increased institutional transparency is the most noticeable effect of EQM in higher education. It seems that evaluations have made the ‘black box’ more open and quantifiable. More information than ever before are published about higher education and its outcomes, and EQM systems are the main driver behind this development. The most apparent consequence of this growth of information is that activities at the department and study level are more vulnerable to institutional and governmental interference. The many cultural effects noticed have not produced the same amount of hard evidence when it comes to organisational change. Actually it is hard to find studies that clearly establish a causal link between cultural change and student learning (even if it is possible to establish such links theoretically, (Barnett, 1994)). Due to this fact, numerous authors have pointed to the need to link EQM systems closer to student needs (Harvey & Knight, 1996; Newton, 2002). Claiming that transparency is the dominant impact of EQM suggests that institutions have not been very active in relating their own quality improvement initiatives to the external procedures. Brennan & Shah (2000) have also documented that EQM schemes usually are decoupled from other measures institutions implement to improve quality. This may, of course, have external causes stemming from intrusive and rigid EQM systems with little opportunity for institutional adjustments and adaptation. However, the main point is that greater transparency is an indication of a procedure that only to a small extent has motivated, engaged 7 and stimulated institutions internally. It is tempting to claim that EQM has rather led to a state of institutional trance — the external stimuli offered has mainly led to a compliance culture. However, due to the fact that EQM systems are difficult to ignore in that they must be responded to, but in a rather formalistic and predictable way, one could also question whether such a procedure really has managed to open the black box of higher education. Higher education institutions are good at playing ‘games’ and have a long history when it comes to protecting their core functions against external threats (Dill 2000). Even if this strategy may pay off in the short run are there some obvious dangers associated with this sort of response. First, growing interest in organisational performance by different external stakeholders, increased pressure for organisational accountability, and the sheer number of EQM systems introduced to higher education during he last decade, could imply that a strategy of ‘keeping up appearance’ in the long run may be difficult to maintain. To protect the organisational core is not easy when organisational autonomy and organisational borders are constantly challenged and penetrated by outside agencies and authorities. Second, the notion of symbolic responses also makes the implicit assumption that groups and actors inside an organisation all have the interest in preventing change, that change seldom occurs, and that higher education organisations, in general, try to ‘cheat’. The image associated with higher education should be something completely different. Also for the academic staff would this position be problematic. Who, in the long run, wants to belong to an organisation that is constantly cheating? Thus, when trying to identify ways to respond to EQM systems symbolic responses represents a danger to organisational survival and prosperity, not least because it is hard to see how symbolic responses may improve quality in the long run. On the other hand, accepting a compliance culture is perhaps not a better alternative. The transformative potential of EQM So far the answer to the question whether EQM has transformed higher education has been ambiguous and not very positive when it comes to quality improvement. The findings support claims from the organisational theorist Henry Mintzberg in that change in professional organisations ‘does not sweep in from (…) government techno-structures intent on bringing professionals under control. Rather, change seeps in by the slow process of changing the professionals (…)’ (Mintzberg, 1983, p. 213). The statement is a very interesting one, especially if one relates it to studies that indicate that EQM, or governmental technostructures in Mintzberg’s terminology, seems to be de-coupled from internal initiatives to improve quality in higher education institutions (Brennan & Shah 2000). Does this mean that EQM has little impact on quality improvement and that only internal initiatives matter? Even if it may be tempting to answer yes would an implication unfortunately be that one creates a picture of intrinsic oriented institutions, unable to relate to a changing environment. It also suggests that it is easy to differentiate between external and 8 internal initiatives and ideas. Echoes of the latter dichotomy can be identified in the ‘accountability vs. improvement’ debate that in an unfortunate way dominated higher education during the major parts of the 1990s. This heated debate, fuelled by EQM developments in the UK, and with a strong ideological and normative bias, contributed to a simplified view on how change in higher education takes place. Instead of seeing change as a dynamic process where interaction between actors and stakeholders take place in a continuum, the accountability vs. improvement distinction actually paved the way for a simple cause-effect model of organisational change, implying that internal initiative always should be associated with improvement, while external initiatives always are related to accountability. However, as Brown (2000) has argued, those who work in higher education have, for a long time, been accountable to students, to disciplines and to their professions. In other words, accountability can be handled internally. Furthermore, there are a number of studies indicating that institutional self-evaluation processes taken on as a part of an EQM process are very useful processes for higher education institutions (Saarinen, 1995; Thune, 1996; Smeby & Stensaker, 1999; Brennan & Shah, 2000). Thus, quality improvement can indeed have external origin. In trying to capture this complexity several authors have argued for the need to balance accountability and improvement (van Vught & Westerheijden 1994). Even if the arguments above support such a balance it is usually those responsible for designing and implementing various EQM systems that have been given the responsibility for taking care of the balancing act (Westerheijden, Brennan & Maassen 1994). Is it here something went wrong? Clearly, establishing EQM schemes that are also related to institutional needs must be a problem for any agency at the system level. The fact that EQM systems have been altered quite regularly during the 1990s is perhaps not only a sign of (design) progress but maybe also frustration? One could argue that a more viable solution could be a more profiled, daring and firm institutional adjustment of the various EQM systems, not least since ‘institutional needs’ tends to differ radically between institutions. Thus, when discussing the transformative impact of EQM in higher education, one also needs to highlight the option that transformation and change is a two-way street. The role of the institutional leadership should here be mentioned in particular as those responsible for mediating between various interests. Arguing for leadership involvement is an old issue highlighted in the EQM literature: the role of leaders is seen as important for introducing and promoting EQM schemes at their own institution (Kells, 1992; Vroeijenstijn, 1995). The problem with such recommendations is not the argument for leadership involvement in the EQM process, but that involvement in itself is seen as sufficient. Studies from Norway show various outcomes of leadership involvement during EQM processes, for example, where the institutional leadership certainly introduces EQM schemes at their institutions, but where they are not able to add anything to the process, leading to disappointing outcomes when it comes to internal quality improvements (Stensaker 2000). On the other hand, the same study also showed the importance of institutional leaders when they displayed a range of strategic and interpretative skills for fitting together the formal objectives 9 related to EQM and the mission and history of their own institution. In this ‘translation’ process they contributed to change in both their own institutions and the external evaluation systems. Thus, a dynamic interaction was created between the EQM systems and the development needs of the institutions. Conclusion To conclude, the transformative impact of EQM for improving higher education cannot be isolated from the relationship it creates with higher education institutions. Disappointing results of EQM so far can, as a consequence, not be blamed on the design and implementation of EQM systems alone, even if many ill-designed systems exist. This conclusion calls for a more dynamic view on how EQM and higher education institutions interact and also for how impact is measured and should be interpreted. It calls, in particular, upon the institutional leadership in higher education institutions to act as ‘balancers’ of the many claims, demands and expectations related to higher education. This role should not be interpreted as a cry for ‘strong’ (autocratic) leadership in the New Public Management understanding of the term (Askling & Stensaker, 2002). However, greater autonomy and increased centralisation of higher education institutions have, in general, given the institutional leadership more visibility and power to play a more important role in policy implementation and organisational change processes as an interest negotiator, a policy translator and as a creator of meaning. Massy (1999) and Dill (2000) have shown how some audit procedures in Europe and in Asia are developed through practical experience and by active consultation between different stakeholders. These systems are in other words created during implementation. Such a procedure represents a break away from a mechanic understanding of the roles and responsibilities of agencies behind EQM and of the institutions supposed to adapt to such schemes, and would represent an adjustment to the complexity that characterises policy implementation and organisational change. References Alkin, M. C. & Stecher, B., 1983, ‘A study of evaluation costs’ in Alkin, M. C. & Solmon, L. C. (Eds.) The Cost of Evaluation (London, Sage). Askling, B., 1997, ‘Quality monitoring as an institutional enterprise’, Quality in Higher Education, pp. 17–26. Barnett, R., 1994, ‘Power, enlightenment and quality evaluation’, European Journal of Education, 29, pp. 165–79. 10 Brennan, J., 1997, ‘Authority, legitimacy and change: the rise of quality assessment in higher education’, Higher Education Management, pp. 7–29. Brennan, J., Frederiks, M. and Shah, T., 1997, Improving the Quality of Education: The Impact of Quality Assessment on Institutions (Milton Keynes, Quality Support Centre and Higher Education Funding Council for England). Brennan, J., de Vries, P. and Williams, R., 1997, Standards and Quality in Higher Education (London, Jessica Kingsley). Brennan, J., 1999, ‘Evaluation of higher education in Europe’, in Henkel, M. & Little, B. (Eds.) Changing Relationships Between Higher Education and The State (London, Jessica Kingsley). Brennan, J. & Shah, T., 2000, Managing Quality in Higher Education. An international perspective on institutional assessment and change. (Buckingham, OECD/SRHE/Open University Press). Brown. R., 2000, ‘Accountability in higher education: have we reached the end of the road? The case for a higher education audit commission’ speech at University of Surrey Roehampton, 24 October. Dill, D. D., 2000, ‘Designing academic audit: lessons learned in Europe and Asia’, Quality in Higher Education, 6, pp. 187–207. Frazer, M., 1997, ‘Report on the modalities of external evaluation of higher education in Europe: 1995–1997’, Higher Education in Europe, 12(3), pp. 349–401. Frederiks, M., Westerheijden, D. F. & Weusthof, P., 1994, ‘Effects of quality assessment in Dutch higher education’, European Journal of Education, 29, pp. 181–99. Gornitzka, Å., Kyvik, S. & Larsen, I. M., 1996, Byråkratisering av universitetene? Dokumentasjon og analyse av administrativ endring, NIFU rapport 3/96. Hackman, R. J. & Wageman, R., 1995, ‘Total quality management, conceptual and practical issues’, Administrative Science Quarterly, 40, pp. 309–342. Harvey, L., 1995, ‘Beyond TQM’, Quality in Higher Education, 1, pp. 123–146. Harvey, L. & Knight, P., 1996, Transforming Higher Education (Buckingham, SHRE/Open University Press). Henkel, M., 2000, Academic Identities and Policy Change in Higher Education (London, Jessica Kingsley). Jordell, K. Ø., Karlsen, R. & Stensaker, B. 1994, ‘Review of quality assessment in Norway: the first national self–evaluation process’, in Westerheijden, D. F., Brennan, J. & Maassen, P. A. M. (Eds.) Changing Contexts of Quality Assessment: Recent Trends in West European Higher Education (Utrecht: Lemma). Kells, H.R., 1992, Self–Regulation in Higher Education. A multi–national perspective on collaborative systems of quality assurance and control (London, Jessica Kinsley). 11 Kells, H., 1999, ‘National higher education evaluation systems: methods for analysis and some propositions for the research and policy void’, Higher Education, 38, pp. 209–232. Kogan, M., 1989, ‘An introductory note’, in Kogan, M. (Ed.), Evaluating Higher Education (London, Jessica Kinsley). Kogan, M., Bauer, M., Bleilie, I. & Henkel, M., 2000, Transforming Higher Education. A comparative study (London, Jessica Kinsley). Massy, W., 1999, Energizing Quality Work. Higher education quality evaluation in Sweden and Denmark (Stanford, Stanford University, National Center for Postsecondary Improvement). Mintzberg, H., 1983, Structure in Fives: Designing effective organizations. (London, Prentice–Hall). Neave, G., 1988, ‘On the cultivation of quality, efficiency and enterprise: an overview of recent trends in higher education in Western Europe’ European Journal of Education, 23, pp. 7–23. Neave, G., 1996, ‘On looking both ways at once: scrutinies of the private life of higher education’, in Maassen, P. A. M. & van Vught .F. A. (Eds.), Inside Academia. New challenges for the academic profession (Utrecht, De Tijdstroom). Newton, J., 2002, From policy to reality: enhancing quality is a messy business. LTSN Generic Centre/The learning and teaching support network, (www.ltsn.ac.ukgenericcentre/projects/qaa/enhancement) PA Consulting, 2000, Better Accountability FOR Higher Education (London, Higher Education Funding Council for England, report 00/36). Reeves, C. A. & Bednar, D. A., 1994, ‘Defining quality: Alternatives and implications’, Academy of Management Review, 19, pp. 419–445. Saarinen, T., 1995, ‘Systematic higher education assessment and departmental impacts: translating the effort to meet the need’, Quality in Higher Education, 3, pp. 223–234. Smeby, J. C. & Stensaker, B., 1999, ‘National quality assessment systems in the Nordic Countries: developing a balance between external and internal needs?’ Higher Education Policy, 12, pp. 1–12. Stensaker, B., 1996, Organisasjonsutvikling og ledelse – Bruk og effekter av evalueringer på universiteter og høyskoler (Organisational Development and Management – The Use and Effects of Evaluations in Universities and Colleges). Report 8/96, (Oslo: NIFU). Stensaker, B., 1999a, ‘User surveys in external assessments: problems and prospects’, Quality in Higher Education, 5, pp. 255–64. Stensaker, B., 1999b, ‘External quality auditing in Sweden: are departments affected?’ Higher Education Quarterly, 53, pp. 353–68. 12 Stensaker, B., 2000, Høyere utdanning i endring. Dokumentasjon og drøfting av kvalitetsutviklingstiltak ved seks norske universiteter og høyskoler 1989–1999 (Transforming higher education. Quality improvement initiatives and institutional change at six universities and colleges 1989–1999). (Oslo, NIFU, report 6/2000). Thune, C., 1996, ‘The alliance of accountability and improvement: the Danish experience’, Quality in Higher Education, 2, pp. 21–32. van Vught, F. A. & D. Westerheijden, 1994, ‘Towards a general model of quality assessment in higher education’, Higher Education, 3, pp. 355–71. Vroeijenstijn, A.I., 1995, Improvement and Accountability, Navigating Between Scylla and Charybdis, Guide for quality assessment in higher education, (London, Jessica Kingsley). Westerheijden, D. F., 2001, ‘Ex oriente lux?: national and multiple accreditation in Europe after the fall of the Wall and after Bologna’, Quality in Higher Education, 7, pp. 65–75. Westerheijden, D.F., Brennan, J. & Maassen, P.A.M. (Eds.), 1994, Changing Contexts of Quality Assessment: Recent Trends in West European Higher Education (Utrecht, Lemma). Weusthof, P. J. M., 1995, ‘Dutch universities: an empirical analysis of characteristics and results of self–evaluation’, Quality in Higher Education, pp. 235–48. Wright, A., 1995, ‘Teaching improvement practices: international perspectives’, in Wright, A (Ed.). Successful Faculty Development: strategies to improve university teaching (Bolton, Anker). Zbaracki, M. J., 1998, ‘The rhetoric and reality of total quality management’, Administrative Science Quarterly, 43, 602–36. 13