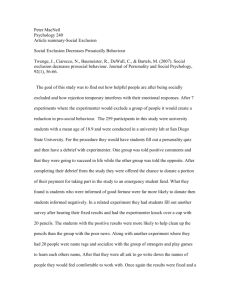

Evidence for the link between emotional and physical pain

advertisement