Chinese Art: Translation, Adaptation and Modalities

advertisement

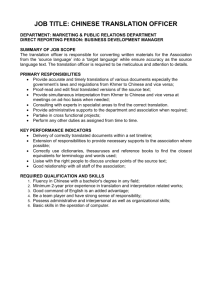

Chinese Art: Translation, Adaptation and Modalities University of Edinburgh, 27-28 October 2011 Thursday, 27 October Venue: Lecture Room 1, School of Arts, Culture and Environment 20 Chambers Street, Edinburgh EH1 1JZ 5.15 – 6.15 Natascha Gentz, Confucius Institute for Scotland in the University of Edinburgh: Introduction Roderick Whitfield, University of London-SOAS Art in Translation: When Buddhism Came to China 6.20 – 9.30 Refreshment and Dinner Friday, 28 October Venue: Teviot Row (Student Union), Dining Room 13 Bristo Square, Edinburgh EH8 9AJ 9.00 – 9.45 Registration and Coffee 9.45 – 10.00 Iain Boyd Whyte, University of Edinburgh Welcome Address: Art in Translation 10.00 – 13.00 SESSION 1: WHY TRANSLATE? Chair: Hsueh-Man Shen, New York University 10.00 – 10.50 Puay-Peng Ho, The Chinese University of Hong Kong Mind the Gap: Will More Translated Works in the Field of Chinese Architectural History Help? 11.00 – 11.50 Michael Nylan, University of California-Berkeley Heritage Issues in Translation: Convergent Preoccupations in Chinese and Western Scholarship 11.50 –12.10 Tea / coffee break 12.10 – 13.00 Chia-Ling Yang, University of Edinburgh Archaic Art and Translated Modernity in China 13.00 – 14.00 Lunch 14.00 – 18.00 SESSION 2: EXOTIC ‘CHINA’ AND EXOTIC ‘WEST’ Chair: Roderick Whitfield, University of London-SOAS 14.00 – 14.50 Youngsook Pak, University of London-SOAS Chaekkori – a Chosŏn Conundrum – 15.00 – 15.50 Alain George, University of Edinburgh China and the Islamic World: Early Encounters in Art and Culture (7th10th century) 16.50 – 16.10 Tea / coffee break 16.10 – 17.00 Yuka Kadoi, Art Institute of Chicago China in Islamic Art after the Mongol Invasions of Eurasia: Centuries of Translations 17.00 – 17.50 18.00 – 21.30 Hsueh-Man Shen, New York University ‘Dragon’ or ‘Long’ in Chinese Art Refreshment and Dinner Each lecture will last for 40 minutes and is followed by 10 minutes for Q&A. Speakers and Abstracts 1. Puay-Peng HO 何培斌 (Professor, Department of Architecture, The Chinese University of Hong Kong) Mind the Gap: Will More Translated Works in the Field of Chinese Architectural History Help? Abstract The development of the field of Chinese and Japanese architectural history, encompassing official and vernacular architectural traditions, cities, gardens and the craft traditions, can be divided into two distinct periods with a significant break between1950-1979. Before the break, Western and Japanese scholars were noted for their pioneering and exploratory research; while Chinese scholars were striving to establish the field with textual and building surveys. Ernst Boerschmann 鮑希曼 (1873-1949), Osvald Sirén 喜仁龍 (1879-1966), Johannes Prip-Møller 艾術華 (18891943), Itō Chūta 伊東忠太(1867-1954), and many others were engaged in discursive studies with reference to art historical methodology from the West, while Liang Sicheng 梁思成 (1901-1972) and Liu Dunzhen 劉敦楨 (1897-1968) who graduated from US and Japanese schools were translating foreign language texts and publishing original research based on first hand materials and adapted methodology. Since late 1970s, there was, on the one hand, a flourish of research in Chinese architectural history within China spearheaded by students of Liang and Liu who applied their methodology to a larger corpus of newly identified architectural monuments. On the other hand, Western and Japanese scholars including Ronald Knapp 那仲良 (1940-), Tanaka Tan 田中淡 (1946-), Frances Wood 吳芳思 (1948-), and Nancy Shatzman Steinhardt 夏南悉 worked tirelessly on a different track and published essentially in English and Japanese. They used first hand information from China through meeting Chinese scholars and visiting buildings and sites. The most likely crossing between Chinese and Western scholarship in Chinese architectural history would be at the intersection of this generation of scholars through the translation of their works. However, this has not been the case. Although the dual edition of Chinese Architecture in English (2002 Yale University Press) and Zhongguo gudai jianzhu 中國古代建築 in Chinese (2004 New World Publishers) seems to go some way to address this gap, there are just a handful of works being translated into either Chinese or English. This paper will explore why translation has never played a major role for scholarly exchanges in shaping the field of Chinese architectural history. One of the major factors might be the perceived lack of interest in translated works in this field because of unequal dominance of research in Chinese. The consequence of such lack of translation has denied both English-reading and Chinese-reading communities access to in-depth research and alternative methodology adopted by scholars in both languages. While the publication of Chinese Architecture in both languages may help to bridge the gap, there are inherent issues involved in the ‘translated’ works which will also be discussed in this paper. Will future generations of researchers in Chinese architectural history become more mindful of the ‘gap’ and see translation as an engaging and necessary exercise to further their field of study? This paper will look into the question of historiography in both Western and Chinese tradition and explore if translation of critical works may help to facilitate exchanges between Chinese and Western scholars in time to come. 2. Michael NYLAN (Professor, Department of History, University of CaliforniaBerkeley) Heritage Issues in Translation: Convergent Preoccupations in Chinese and Western Scholarship My paper will discuss examples from China, Europe, England, and the United States of key figures operating in art history and in the international art markets, whose work was influential in developing, through complex processes of cross-pollination and selection, enduring standards for “East Asian Art” that tended to emphasize certain artistic values in ways we would now characterize as Orientalization and selfOrientalization. 3. Chia-Ling YANG (Lecturer in Chinese Art, University of Edinburgh) Archaic Art and Translated Modernity in China Within China, nationalistic sentiments notably inhibit objective analysis of SinoJapanese and Sino-Western cultural exchanges during the end of the Qing throughout the Republican period. Despite the fact that China was occupied by external and internal powers, that China was not governed or united by one political body; their contemporary concept of ‘China’ as ‘one nation’ and how ‘Chinese art’ is defined, translated and adopted by the Chinese and non-Chinese readers are still in debate. Furthermore, the on-going archaic movement brought by influential artists, whose advocacy of 'traditional' culture seemed be inspired by the Western discipline of archaeology, yet antithetical to European-inspired modernist movements. Taking the cultural production in foreign colonized cities of Chinese coast-boarders as example, this paper questions how polarisation of ‘indigenous tradition versus translated modernity in visual production’ has been promoted during the subsequent Republican era (1911-1949). Central to this is the position of the artists and intellectuals in cultural history of early twentieth-century China, and in a wider context, the transnational and translingual art and the cultural heritage in global East Asia. 4. Youngsook PAK (Reader in Korean Art, University of London (SOAS), Emeritus) Chaekkori – a Chosŏn Conundrum Abstract A screen depicting bookshelves (in Korean chaekkori 책거리, drives from chaekka 冊 架) starts to appear in the eighteenth century in Korea. In the shelves one finds not just books neatly stacked, but all kinds of fine objects, ink stone and brush, seal and papers, flowers in pot in bonsai style, antique bronze vessels, porcelains, fans, exquisitely arranged, almost like a still-life. The intriguing fact is that although the genre is unmistakably Korean, the objects found in chaekkori were all from China. The paper will analyze the iconography and function of such chaekkori and the phenomenon of the sudden appearance of and preference for Chinese items in the environment of Korean Confucian scholars in the latter period of the Chosŏn Dynasty (1392-1910). 5. Alain GEORGE (Lecturer in Islamic Art, University of Edinburgh) China and the Islamic World: Early Encounters in Art and Culture (7th-10th century) Between the 7th and 10th centuries, China and the Islamic world concurrently reached a peak in their political and cultural power. The territorial expansion of the Tang and Abbasid empires gave them a shared frontier in Central Asia. The stability and wealth which these two empires mustered for much of the period also favoured the development of direct sea trade between Iraq and the South China sea. For about two centuries, both ends of the Asian continent thus came to be linked on an unprecedented scale, notably through extensive trade in luxury goods. Underlying this pattern of exchange were human networks primarily driven by commerce, and also by religion and politics, which enabled the transmission and translation of artistic forms, technologies, and possibly written words, across Asia. In the present paper, I will outline the parameters of this fascinating phase of cultural exchange that reached far beyond the level of courtly circles, and engage in a reflection about the barriers, filters and facilitators involved. 6. Yuka KADOI (Curator of Department of Asian and Ancient Art, Art Institute of Chicago) China in Islamic Art after the Mongol Invasions of Eurasia: Centuries of Translations This paper looks at the cycle of translating and retranslating Chinese art traditions in the arts of Islam from the 7th century to early modern times, especially the case of the Iranian world which historically went into a close contact with East and Central Asian cultures through trades and diplomatic exchanges. This serves to offer a unique insight into the pattern of translating an apparently homogeneous art form, such as that of Chinese art, into other visual languages. The paper also highlights the portability and translatability of the ‘object’ in the transmission of ideas across different cultures. 7. Hsueh-Man SHEN (Assistant Professor, Institute of Fine Art, New York University) Dragon’ or ‘Long’ in Chinese Art For this conference I propose to do a case study on ‘long (dragon)’ images in Chinese art. I will look at the ways in which the Chinese term ‘long’ is being applied to archaeologically excavated objects (such as neolithic jades) that may not have been associated with the mythical creature ‘long’ in the first place. I will argue that our understanding or interpretation of such objects is very much mediated by the terms we use to describe them. I will also use Lü Dalin’s Kao gu tu as an example to see how (illustrated) texts could manipulate our knowledge of ancient bronzes and jades. Moreover, when the Chinese term ‘long’ is translated into ‘dragon’ in English, it immediately forms a visual image in our mind that pairs the two groups of mythical creatures, East and West. I shall discuss the advantage and disadvantage of such translation in art historical writings.