Ch. 8 Notes - Newsome High School

advertisement

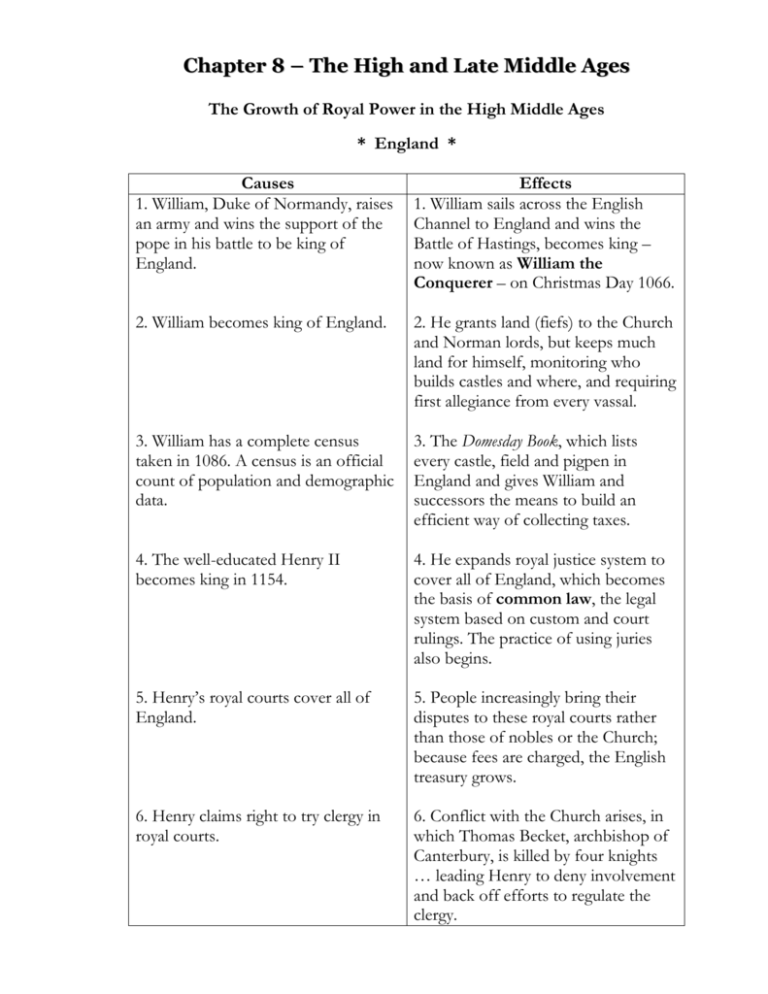

Chapter 8 – The High and Late Middle Ages The Growth of Royal Power in the High Middle Ages * England * Causes 1. William, Duke of Normandy, raises an army and wins the support of the pope in his battle to be king of England. Effects 1. William sails across the English Channel to England and wins the Battle of Hastings, becomes king – now known as William the Conquerer – on Christmas Day 1066. 2. William becomes king of England. 2. He grants land (fiefs) to the Church and Norman lords, but keeps much land for himself, monitoring who builds castles and where, and requiring first allegiance from every vassal. 3. William has a complete census taken in 1086. A census is an official count of population and demographic data. 3. The Domesday Book, which lists every castle, field and pigpen in England and gives William and successors the means to build an efficient way of collecting taxes. 4. The well-educated Henry II becomes king in 1154. 4. He expands royal justice system to cover all of England, which becomes the basis of common law, the legal system based on custom and court rulings. The practice of using juries also begins. 5. Henry’s royal courts cover all of England. 5. People increasingly bring their disputes to these royal courts rather than those of nobles or the Church; because fees are charged, the English treasury grows. 6. Henry claims right to try clergy in royal courts. 6. Conflict with the Church arises, in which Thomas Becket, archbishop of Canterbury, is killed by four knights … leading Henry to deny involvement and back off efforts to regulate the clergy. * France * Causes 1. Nobles elect Hugh Capet to the French throne in 987, believing his power won’t challenge theirs. Effects 1. Hugh and his heirs create a stable, 300-year-long dynasty by making the throne hereditary, passing it from father to son. They win the support of the Church and play rival nobles against one another. 2. The Capetians build an effective bureaucracy. 2. Government officials establish order by collecting taxes and imposing royal law over the king’s lands, thereby increasing their prestige and winning the support of the new middle class. 3. Philip Augustus becomes king of France in 1179. 3. He appoints middle-class officials to government posts rather than nobles, introduces a national tax and quadruples the royal land holdings through trickery, diplomacy and war – becoming the most powerful ruler in Europe by the time he dies in 1223. 4. Louis IX becomes king in 1226. 4. He improves royal government by a) sending roving officials to check on local administrators, b) expanding royal courts, c) outlawing private wars, and d) ending serfdom in his personal domain. 5. Louis’s grandson, Philip IV, extends 5. A dispute with Pope Boniface VIII royal power and tries to collect new develops, in which Philip IV sends taxes from the clergy. troops to capture him. The pope escapes but soon dies. 6. A Frenchman soon after is elected pope. 6. That French pope moves the papal court to Avignon, near France, where French rulers can better control it … which eventually leads to a crisis in the Church when a rival pope is elected in Rome. 7. During the crisis in the Church, Philip rallies French support in 1302 by setting up the Estates General, a representative body of all three classes of French society: clergy, nobles and townspeople. 7. Estates General was from time to time consulted by French kings, but it never gained the power of the purse or otherwise could balance royal power. King John and the Magna Carta Q&A Question: Describe the rule in England of King John. Answer: King John was a cruel and untrustworthy ruler who struggled with various enemies. He lost a war in 1205 to Philip II of France, after which he had to give up lands in France that Norman rulers of England had held ever since William the Conqueror’s days. John was then excommunicated by the pope when he rejected the pope’s nominee for the new archbishop of Canterbury. Finally, he angered his own nobles with various abusive tactics, such as oppressive taxation. Things got so bad that a rebellious group of barons cornered him in 1215 and forced him to sign the Magna Carta, or great charter, which proved to be the first “baby step” toward democracy centuries later. Question: Explain the political significance of the Magna Carta, signed in 1215. Answer: It established two important concepts that shaped English government going forward. First was the basic idea that nobles had certain rights … and over time, these rights filtered down to the lower classes as well. Secondly, this document made it clear that the monarch must obey the law. Question: Explain the important legal provisions established by the Magna Carta. Answer: It established “due process of law,” which protected freemen from arbitrary arrest and imprisonment, and the right of habeas corpus, which was the principle that no person can be held in prison without first being charged with a specific crime. Question: The Great Council of lords and clergy evolved over time into Parliament, England's legislature. Explain how this body could limit the power of the monarch. Answer: By signing the Magna Carta, King John agreed not to raise new taxes without first consulting the Great Council. Over time, as this body became a two-house legislature – featuring a House of Lords with nobles and high clergy, and a House of Commons with lower-class knights and middleclass citizens – it gained the critical “power of the purse,” or right to approve any new taxes. This was in stark contrast to France’s legislature – the Estates General – which never gained this ability to check the power of the monarch. The Holy Roman Empire What came to be called the Holy Roman Empire covered much of central and eastern Europe by the late-10th century. You can think of it as essentially Germany, because that’s what it was at its core. But Germany didn’t unify into the modern nation-state that it now is until the 19th century. It remained a collection of hundreds of city-states, or principalities. Rulers who took the title of Holy Roman Emperor were not nearly as powerful as the name implies. The German emperors could not control their hundreds of vassals, including nobles and Church officials. This is why the French philosopher Voltaire later said of the Holy Roman Empire: “It was neither holy, nor Roman, nor an empire.” Holy Roman Emperors, however, did become involved in a notable clash with the Roman Catholic Church – something that illustrates the rising tension between monarchs and the pope. Things first came to a head in the 11th century when the German king Henry IV challenged Pope Gregory VII’s ban on lay investiture. Gregory wanted to make the Church independent of secular rulers, so he banned this practice of emperors or other lay individuals (people who are not members of the clergy) “investing,” or presenting bishops with the ring and staff symbolizing their office. Henry and Gregory exchanged insulting letters, and Gregory excommunicated Henry in 1076. This struggle over the issue of lay investiture lasted for more than 50 years before it was finally settled with the compromise of the Concordat of Worms, a treaty that declared that the Church alone could elect and invest bishops with spiritual authority, while allowing the emperor to still invest them with fiefs. The Crusades The Crusades were a series of wars between Christians and Muslims for control of Mideast lands (including those of modern-day Israel) on which both sides considered to have holy sites important to their religions. They began in 1096 and lasted for about 200 years. The First Crusade began after the Byzantine emperor (we’ll learn more about the Byzantine Empire in the next chapter, but for now understand that it was the eastern half of the old Roman Empire that continued to exist until 1453) urged Pope Urban II to send Christian knights to help him fight Muslim Turks, who had taken over Byzantine lands in modern-day Turkey and now controlled the Holy Land, which included Jerusalem and other places in Palestine where Christians believed Jesus lived and preached. Urban agreed, even though the Roman and Byzantine churches had earlier in the 11th century split into two branches of Christianity. Thousands of crusading knights – as well as other men, women and even some children – set off from Europe to the Middle East. They were motivated by religious zeal, but many knights hoped to win wealth, land and prestige. Others were fleeing troubles at home or simply yearning for adventure. Only the First Crusade came close to achieving its goals, from the European perspective. Christian knights captured Jerusalem in 1099, in the process massacring Muslim and Jewish residents in the city. The crusaders divided their captured lands into four small states, called crusader states, which surrounding Muslim armies repeatedly tried to destroy … which in turn led Europeans to launch new crusades. In 1187 Jerusalem fell to the Muslim leader Saladin. Subsequent crusades were unsuccessful: The Third Crusade failed to retake Jerusalem, and the Fourth Crusade saw Christians fighting Christians. The Fourth Crusade weakened the Byzantine Empire so deeply it never recovered, shrinking to a mere city-state before being taken over by invading Muslims in 1453. After European knights helped merchants from the northern Italian city of Venice defeat their Byzantine trade rivals in 1204, they looted the Byzantine capital city of Constantinople. The Crusades came to an end in 1291, when Muslims overran the last Christian outpost in the Mideast, massacring Christians in the process. The impacts of the Crusades were significant: The economy of western Europe picked up as trade increased. This was due to crusaders bringing back fabrics, spices and perfumes from the Mideast (and thereby increasing demand for more of them), and the large fleets of Italian city-states – built initially to carry crusaders to the Holy Land – now being used to facilitate trade between western Europe and the rest of Eurasia via the Mediterranean. The resulting money economy also hastened the end of serfdom. The power of monarchs increased because they had won prestige from their Christian subjects and new rights to collect taxes to support the Crusades. The division and resentment between the eastern and western branches of Christianity (the Eastern, or Greek Orthodox Church and the Roman Catholic Church) deepened. Contacts with the Muslim world led Christians in western Europe to a greater curiosity about the outside world. They were re-exposed to the classic works of the Greeks and Romans – which Muslim scholars helped to preserve – and soon began traveling to India and China. The long-term animosity between Christians and Muslims, sadly, continues to this day. The Reconquista and Spanish Inquisition Even after the Crusades ended, the crusading spirit continued on the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal). North African Muslims called Moors had conquered most of present-day Spain in the 700s, and the campaign by Christians to drive them from Spain became known as the Reconquista, or “reconquest.” This lasted through much of the High and Late Middle Ages, finally being completed in 1492 by the monarchs of Spain, Ferdinand and Isabella. In contrast to the relative peace under Muslim rule, Ferdinand and Isabella presided over a very intolerant time of persecution of Jews and Muslims, forcing them to convert to Christianity. Under the Inquisition, a Church court set up to try people accused of heresy, those found guilty of practicing a religion other than Christianity could be tortured or burned at the stake. This imposition of religious unity was very costly for Spain, because about 150,000 Muslims and Jews fled the country – and many were skilled, educated individuals who had contributed much to Spain’s economy and culture. Learning and Culture As economic and political conditions began to improve in the High Middle Ages, the need for education expanded. The Church wanted better educated clergy and monarchs needed literate men for their growing bureaucracies. By the 1100s, schools sprung up around the great cathedrals of Europe, and these eventually evolved into the first universities. One important boost to this new emphasis on learning came from Muslim scholars, who had translated the ancient works of Aristotle and other Greek thinkers into Arabic. In Muslim Spain, Jewish and Christian scholars translated these works into Latin – and these translations reached western Europe by the 1100s, reintroducing classical ideas that had all but been forgotten there. The writings of Aristotle, however, posed a problem for Christian scholars. Aristotle had taught that people should use reason and logic to discover basic truths, yet Christians relied on faith and believed the Church had the final authority on all questions. So scholars tried to resolve this conflict between faith and reason through the philosophy of scholasticism, the father of which was Anselm of Canterbury. Under scholasticism, reason was used ultimately to find justifications or support for Christian beliefs. The most famous scholastic was Thomas Aquinas, who concluded that faith and reason exist in harmony and lead to the same truth – that God rules over an orderly universe. Because scholars believed all true knowledge must fit with Church teachings, then, science made little real progress in Europe during the Middle Ages, though some advancements were made in studying the physical world. One notable feature of medieval culture was the construction of impressive cathedrals using the Gothic style of architecture, the most important feature of which was the flying buttresses, or stone supports that stood outside the church (study the illustration of p. 82). Gothic churches had vaulted ceilings that soared to incredible heights because the flying buttresses allowed builders to construct higher, thinner walls and leave space for large stained-glass windows that allowed in light as if from the heavens. A Time of Crisis: the Black Death and Hundred Years’ War Q&A Question: What weakened Europe’s population in the early 14th century and made the people there especially susceptible to the Black Death in the middle of the century? Answer: The Great Famine of 1315-1317 – caused by heavy rains and severe weather – led to mass starvation and undernourished, unhealthy urban workers. Question: The Black Death was an especially severe case of the bubonic plague that killed many millions of people, including one in three in Europe. How did this epidemic disease spread? Answer: It was spread by a bacteria carried by the fleas on rats, which got into the packs of merchants traveling trade routes from Asia to Europe. Question: Where did the Black Death originate? Answer: It originated in China. Question: How did people react to the Black Death? Answer: People fled to the countryside or hid in their homes to avoid contact with their neighbors. Some turned to magic and witchcraft in a futile attempt to find a cure for the disease. Some Christians unjustly accused Jews of starting the plague by poisoning wells. Survivors demanded higher wages, which led to inflation and a ruined economy, which in turn led angry peasants to rampage across England, France, Germany and elsewhere. Question: Describe what divided the Church during the upheaval of the 14th century. Answer: Many priests and monks died during the Black Death, and the Church could not provide answers for all the death and misery across European society. The power of the Church was further weakened by a schism, or split, caused by a pope moving the papal court from Rome to Avignon, outside the border of southern France. For about 70 years the French dominated the court, living in luxury – which caused critics to lash out against the Church’s worldly, pleasure-loving papacy. Reformers in 1378 elected their own pope to rule the Church from Rome, and French cardinals responded by choosing a rival pope. For decades there were two and sometimes three rival popes claiming to be the true “vicar of Christ.” All this contributed to an increase in anticlerical sentiment. Question: Who fought in the Hundred Years’ War, and what was the source of the conflict? Answer: England and France fought in this war, which was a series of offand-on conflicts spanning 1337 to 1453. It broke out initially when King Edward III of England claimed the French crown because his mother had been a French princess. The two countries fought for control of French lands that had been held for centuries by the Norman ancestors of William the Conqueror. Question: Summarize the course of war, including which side won early victories (and why) … and which side ultimately prevailed (and why). Answer: The English won a string of early victories using a new weapon, the longbow. The tide began to turn for two reasons. First, a young French girl named Joan of Arc – who’d been having visions and hearing in her head the voices of saints (or so she believed) urging her to drive the English from French lands and hand the French crown to the true French king, Charles VII. When she appeared at his court, he authorized her to lead an army against the English. She led France to a string of victories, but was then captured by allies of the English, who tried her for witchcraft and then burned her at the stake. The French saw her as a martyr, took the offensive, and then – with the help of another new weapon, the canon – drove the English from French territory, thereby winning the Hundred Years’ War. Question: Explain the impact of the Hundred Years’ War. Answer: The war created a rising sense of national pride in the French, which allowed the French kings to expand their power. The rulers in England, meanwhile, had turned repeatedly to Parliament for funds to fight the war – so kings there were kept in check by a representative body of the people. England soon turned toward overseas trade ventures. The war’s introduction of the canon, meanwhile, brought to an end medieval warfare and its reliance on armored knights and castles.