Social and demographic changes and their spatial effects – the

advertisement

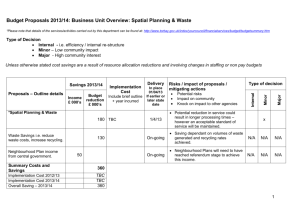

Social and demographic changes and their spatial effects – the Czech experience Karel Maier Czech Technical University in Prague The paper uses the outcomes of the research projects supported by the Czech Ministry for regional development: WD-07-07-4 Koncepce územního plánování a disparity v území – Planning concepts and territorial disparities (Czech Technical university in Prague) WD-40-07-1 POLYREG – Podpora polycentrického regionálního rozvoje – Support for polycentric development (Masaryk University in Brno) Presently existing patterns of spatial change While the spatial change in the period of state-controlled economy was entirely subordinated to central government, since 1990 onwards virtually all spatial change is driven by individual choices wherever planning environment has been rather weak and often without clear vision, mission and objectives. The change from overall control to individual choice was abrupt, which did not allow for developing relevant institutional environment, and also awareness of the significance of the issue. Selected accessibility has become a new phenomenon typical both for certain remote areas and also newly emerging sprawled suburbia, and for a newly emerging disprivileged poor and elderly people who cannot drive. The changes have been towards the existing spatial pattern of current west-European cities and as such they would not have deserved special attention. However, there are several features that may make the changes worth deeper consideration. First, this is the relative size and speed of the change, which expose the affected areas and communities to various challenges and pressures: Second, the absorbing capacity of the country, its economy and 1 society may be severely burdened as the external frameworking conditions are different from what framed the spatial change in western Europe in the period between the end 1950s and the 1980s (nowadays there is less capacity and also willingness to compensate the affected people and regions than it was in the case of Western Europe). It is quite easy to prove these changes by empirical (quantitative) research – e.g. by demographic statistics, census, planning permissions. Upcoming changes Demographic change have increasingly influenced spatial pattern of urban areas since the 1990s, consisting in ageing of the population, caused by several factors, namely: • increased life expectation • delayed marriages and births • low birth rates The population decline has not been significant yet as it is compensated by migration mostly from • outside EU (Vietnam, Ukraine, Russia, Mongolia) • inside EU from outside CZ (Slovakia) • inside CZ (in fact, the move from rural parts to cities almost stopped in the 1990s and since it is not significant in numbers of people) Beside the demographic change, the economic liberalisation since the mid-1990s resulted in varied prosperity between • metropolitan area of Prague • prosperous regional centres • rural country • old industrial parts 2 Qualitative spatial change increased spatial disparities This change stems from societal change from rather homogeneous, middle-class based society towards much more contrasted pattern of social groups with new rich as well as new poor on the account of shrinking middle class. However, the very term of middle class was not used for the mainstream societal group in the so-called socialist countries, and also the living standards of the “socialist middle-class” were quite different from what would be considered middle-class in the West. The diversification and polarisation of the society is accompanied with increasing part of elderly people (owing to decreasing birth ratios, postponing births and increasing average life expectation). Elderly people are much more frequently also poor people. Migrants from abroad are new phenomenon in the East-Central Europe, coming from Eastern Europe, Balkans, some countries of the former Soviet Union, Vietnam, China and Mongolia. They also mostly belong to rather poor but also rich people can be found among them, often considered to be connected with grey and even illegal economy. RICH RICH MIDDLE CLASS elderly migrants elderly MIDDLE CLASS POOR POOR 1990 towards 2020 The spatial imprint of the social polarisation follows in certain respect the spatial pattern of western European city regions but it still retains some specific features. Housing estates which accommodate remarkable percentage of national population (30% in the Czech Republic) have changed from middle-class mostly young family housing, as they were at time of their origins in the 1960s to 1980s, in residences of elderly and, increasingly, migrants and other transitory population. Exclusion enclaves emerged especially in old working-class districts and housing estates in declining old industrial regions. On the other side, gentrification is changing certain attractive historical cores as well as certain selected inner-city districts. 3 Emerging new pattern of functional city region 4 Population ageing: selective problem of places on local scale Czech Republic – cities of Praha, Plzeň, České Budějovice, Hradec Králové, Pardubice big housing estates in selected Czech cities (Praha, Plzeň, České Budějovice, Hradec Králové, Pardubice) 5 On regional and national scale, move of young, educated people can be estimated (but not proved, owing to lack of the data until the next census in 2011) from eastern part of the country and from peripheral, rural and old industrial regions to Prague and, to lesser degree, also to other large centres especially in western and southern part of the country. While the quantitative changes in terms of population numbers are not big except for the relative growth in suburban satellites of big cities, the “qualitative” change of population in different parts of urban regions and nationally seems to be significant. As there is lack of a less empirical (quantitative) evidence, these are rather hypotheses based on some evidence of case studies. The “less-measurable” issues may prove to be essential but the contemporary science (and science-driven policies) tends to underestimate the “dubious” observations / opinions without scientific proofs. The research should therefore focus on the less palpable, “soft” evidences. All these hitherto / recent changes in the physical urban space are extremely controversial vis-à-vis the upcoming change of external constraints in the respect of urban spatial pattern. 6 Issues, challenges and their management Newly emerged issues • • • • • • control and safety • released control increased unsafety • personal • property (from pickpockets to burglary) privatisation of safety control • real emergence X perception of crime risk climate hazards floods accessibility services jobs Upcoming challenges • ageing population • decreasing social cohesion • peak oil? Arena for management of the changes • poorly pronounced public interest • national strategies & frameworks follow EU guidance • weak role of regional governance local decisions under control of local power groups and developers • development-oriented public opinion • civic groups treated as problem-makers X NIMBY Diversified impact of the challenges on particular • regions • cities • neighbourhoods • SOCIAL GROUPS WINNERS X LOSERS Which game? • • • win – win? zero sum? lose – lose? 7 Recommendations planning • • Top-down side of planning is still very important in the environment which inherited the continental (Napoleonic, Bismarck, Habsburg) style of governance. Top-down approach is necessary wherever individual and particular interests would prevent from implementation of changes that are desirable for the whole • inward-oriented development policy instead of the laissez-faire approach towards development • internalisation of service costs – the principle of collection of a “service charges / taxes” should be expanded and differentiated according to site of a user; in the case of new developments, the developers should be obliged to provide the site with relevant infrastructures (paradoxically, this had existed in Czechoslovak planning before 1989) • enforcement of standards for new residential design (included any changes of existing urban areas) o passable neighbourhoods – to prevent from physical fragmentation of urban environment as a precondition for any other actions towards accessibility and openness o small-grained rather homogeneous units – a compromise instead of the ideal of social mix, which is impossible to achieve – but certain grain of the mix should be enforced, even against particular interests of “market” represented by developers, communities and local politicians in municipalities and boroughs o compact cities – this concept of urban life is traditional for most of the continental Europe and the living in close proximity to other people, services, facilities and jobs has been appreciated by many central Europeans. New technologies make possible to avoid some problems connected with closeness (e.g. privacy by noise insulation) but the essential precondition for the desirable form of compactness rests in providing feeling of safety and security both in public and private space o small-distance cities – apparently the only concept that can respond the challenge of peak energy and low carbon economics in urban environment; however it should expand from the relationships between housing, services, facilities and jobs to provision of goods and products (urban agriculture, local / regional markets) „soft“ • campaign for better awareness of long-term impact of social fragmentation o Sustainable Cities is a very good example governance • new supra-municipal tier of governance • management of spatial changes – particularly urban sprawl / suburbanization, increasingly also of social spatial fragmentation / polarization • co-ordinated development / provision of services and facilities – vis-a-vis diminishing resources this needs to be closely coordinated with the abovementioned spatial management • co-ordinated development of transportation infrastructure – the same reasoning as above 8 9