Full Text (Final Version , 727kb)

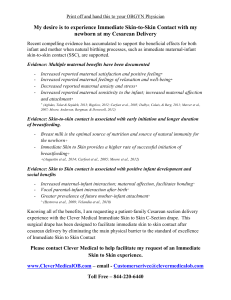

advertisement