End of Fairness At the FTC

advertisement

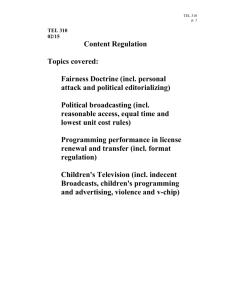

End of Fairness At the FTC? New York Law Journal February 8, 1985 James C. Goodale, former vice chairman of The New York Times, is a partner at Debevoise & Plimpton and an adjunct professor of communications law at New York University School of Law. Robert R. Bruce, former general counsel of the Federal Communications Commission, is also a partner at Debevoise & Plimpton. Repeal Would Cause Tilt in Congress Today, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) concludes two days of hearings in a far-reaching proceeding1 that examines its “Fairness Doctrine” — which requires that broadcasters present balanced coverage of controversial issues.2 The repeal of the Fairness Doctrine would be one of the most significant steps that the Commission could take. It also would be one likely to provoke a donnybrook of major proportions in Congress. Critics of any effort to modify the Fairness Doctrines — who include House Energy and Commerce Committee Chairman John Dingell — contend that only Congress can change it. They believe that Congress codified the doctrine when it passed an opaque amendment to the Communications Act in 1959. The Fairness Doctrine states that a broadcaster — as a “trustee” — must both devote a reasonable percentage of time to the coverage of controversial issues and provide a reasonable opportunity for the presentations of contrasting viewpoints on such 1 See inquiry note §78.1910 of the Commission’s Rules and Regulations Concerning the General Fairness Doctrine Obligations of Broadcast Licensees, 60 Fed. Reg. 20.817 (1984) [hereinafter cited as Fairness Doctrine Inquiry]; Amendment of Part 76, Subpart G of the Commission’s Rules and Regulations Concerning the Fairness Doctrine and Political Cablecasting Requirements for Cable Television Systems, 45 Fed. Reg. 26,472 1983) [hereinafter cited as Cable Fairness Inquiry]. 2 The Fairness Doctrine is found at 47 C.F.R. §73.1010 (1983). The Doctrine is made applicable to cable channels over which the system operator retains editorial control by 47 C.F.R. §76.700 (1983). 60.doc issues.3 This is because a broadcast license is thought to be a user of a scarce resource — spectrum — which it holds “in trust” for the public. A broadcaster — as a “speaker” protected by the First Amendment — retains, however, significant discretion as to precisely what issues should be covered, how they will be presented, and which speakers will be used to provide contrasting viewpoints. This regulatory approach thereby serves the First Amendment goal of minimizing governmental interference with speech. Why Repeal? Supporting repeal of the doctrine in the present FCC proceeding are not only the broadcast groups, but also the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTLA). Their position is that any government intrusion into the editorial decisions of the electronic press is flatly inconsistent with the First Amendment. There is no regulation of the print media so that, they argue, there should be no regulation of the electronic press either. The Fairness Doctrine does not apply to newspapers: in 1974 the Supreme Court struck down as unconstitutional a state statute imposing a rightof-reply obligation on the Miami Herald.4 ABC and Group W have, however, argued for a more “selective pruning” of the doctrine — that the Commission should move “prudently and cautiously” in reassessing its longstanding policy. Advocates of reform or repeal claim that it actually frustrates, rather than furthers, its constitutional purpose. They contend that the doctrine actually “chills” speech and contributes to blandness in programming. Rather than risking violation of the doctrine, or having to devote substantial time to public controversies broadcasters, they claim, simply decline to venture into investigative reporting or coverage of matters of public interest. Finally, the constitutional underpinnings of the doctrine have eroded — largely as a result of technological change. As the number of media outlets to serve the public has increased, it is difficult to distinguish broadcasters from the print media for constitutional purposes. 3 The FCC’s original, and most comprehensive, explanation of the Fairness Doctrine obligations imposed on broadcasters is found in Report on Editorializing by Broadcast Licensees, 18 F.C.C. 1946 (1999). 4 Miami Herald Publishing Co. v. Tornillo, 615 U.S. 241 (1974). 2 60.doc Since 1980, the FCC has moved aggressively to license a variety of new media — the proverbial alphabet soup of low power television (LPTV), multipoint distribution service (MDS), and direct broadcast satellite (DBS). It also has increased the use of UHF frequencies5 and added more slots for ratio and televisions outlets.6 Finally, cable television has been left relatively free to expand the number and kind of services that it may offer.7 Taken together, these media outlets have provided critics of the Fairness Doctrine with strong arguments that the electronic media are far less scarce today than before and, indeed, far surpass the print media in number. Although the number of newspapers has declined steadily, from 1,772 in 1950, to 1,712 in 1982, the number of radio and television stations alone has exploded, going from 2,965 in 1950, to 10,422 in 1983.8 FCC Finds Few Violations Since 1979, the Commission has found just one broadcaster to have violated the Fairness Doctrine by presenting an “imbalanced” view of a controversial issue.9 In that case, involving the airing of editorial advertisements advocating construction of a nuclear power plant, the FCC found that WTVH-TV, Syracuse, N.Y., showed more than 187 minutes of news and advertising that heralded the plant as a “sound investment,” while allotting just twenty-two minutes for the contrasting viewpoints. Much of this record has been achieved, however, by side-stepping many thorny political disputes. For example, last month the Commission rejected a complaint by the CIA that ABC had violated the Fairness Doctrine by inaccurately discussing an issue that 5 See, e.g., Improvements to UHF Television Reception, 67 Fed. Reg. 36,976 (Aug. 18, 1992) 6 See, e.g., Modification of FM Broadcast Station Rules to Increase the Availability of Commercial FM Broadcast Assignments, 94 F.C.C. 31 168 (1995), modified in part, 97 F.C.C. 2d 370 (1963), (“District 89-99”); Petition to Add New VHF Stations in the Top 100 Markets and to Assure that the New Stations Maximize Diversity of Ownership, Control and Programming, 90 F.C.C. 2d 100 (1988) (“VHF Drop-Ins”). 7 See, e.g., Cable Television Syndicated Program Exclusivity Rules, 79 F.C.C. 2d 683 (1999). 8 Fairness Doctrine Inquiry, supra note 1, at 20,899-94. 9 In re Syracuse Peace Counsel, 87 Red. Reg. 24 (P&F) 810 (1994). 3 60.doc the complainant characterized as “the participation by the Central Intelligence Agency in illegal acts, including assassination.”10 the Commission, in noting that it is not the “national arbiter” of truth in news programming, stated that the CIA’s complaint was deficient in a number of procedural aspects. As the CIA’s complaint was being dismissed, the conservative, Washington-based American Legal Foundation (ALF), brought another complaint against ABC on the same grounds. The ALF contends that it has the evidence needed to rouse the Commission into taking action, including statements from regular viewers of ABC News. Jumping FCC Hurdles The ALF complaint — as have others — has to jump a series of procedural barriers to provoke the FCC into sanctioning a licensee. A complainant must demonstrate that (1) it has presented the broadcaster with its complaint and that the broadcaster responded unreasonably; (2) the issue being treated by the broadcaster is one of controversy and public importance in the viewing community; (3) there is a lack of balance in the broadcaster’s overall programming on the issue; and (4) the complainant, or its members, regularly view the broadcaster’s programming at all times of the day.”11 These hurdles have allowed the FCC to avoid assessing most controversial programming and have guaranteed that government regulation be as unintrusive as possible. At the same time, they raise the question of whether the doctrine, at present, is really effective. The dearth of complaints may well mean that broadcasters can and do satisfy their fairness obligations, and that coverage of controversial issues is balanced. It is equally possible, however, that the lack of violations stems from the broadcasters’ fear of violating the doctrine, which results in an infrequent airing of programs on matters of public controversy. Discretion to Abolish the Doctrine? The Fairness Doctrine, even in its already weakened incarnation, still has many supporters. Not only “public interest groups,” but also groups as diverse as the Democratic National Committee, the ACLU, and Phyllis Schlafly’s Eagle Forum all contend that the policy is an important check on the power of broadcasters to mold public opinion. 10 In re Central Intelligence Agency, 87 Red. Reg. 2d (P&F) – (1996). 11 See The Managing of Public Issues Under the Fairness Doctrine and the Public Interest Standards of the ?????? Act, ?? F.C.C. 2d 1 (1974). 4 60.doc The doctrine was originally framed in a set of obligations promulgated in 1949.12 The FCC had interpreted the “public interest” standards of the 1934 Communications Act (1934 Act) to require that broadcasters serve the public by presenting controversial issues in a balanced way. In 1959, however, Congress amended Section 315 of the 1934 Act (which dealt with the so-called “equal time” requirement with respect to airtime for political candidates). The amendment stated that nothing in the statute should relieve broadcasters from the obligation imposed upon them under the 1934 Act “to operate in the public interest and to afford reasonable opportunity for the discussion of conflicting views on issues of public importance.”13 If this phrase is read as having directly and statutorily imposed the Fairness Doctrine on broadcasters, then the Commission’s discretion is quite limited. There are significant scholarly arguments for this view.14 Supporters of this reading of the statute point to Red Lion Broadcasting Co. v. FCC,15 in which the Supreme Court said that Congress, through the 1959 amendment, had itself announced that the “public interest” standard imposed certain duties on broadcasters to discuss both sides of controversial issues.16 Others, apparently including the FCC, believe that the 1959 amendment did not codify the doctrine, thus leaving intact the Commission’s discretion to modify or to abolish it. In two ongoing proceedings the FCC has stated that the legislative history, coupled with the thrust of congressional intent, may warrant a liberal reading of the statute.17 Under this view, it is argued, Congress meant only to impose Fairness Doctrine obligations in the political “equal time” context; which is the subject of Section 315 attention, and did not intend to codify the doctrine. 12 See supra note 8. 13 Act of Sept. 14, 1999, §1, Pub. 1. Mo. 69-874, 73 Stat. 966 (1999) (codified at 47 U.A.C. §311(a)). 14 See Fairness Doctrine Inquiry, supra note 1, at 20,241-42. 15 366 U.S. 367 (1999). 16 14 at ????. 17 See Fairness Doctrine Inquiry, supra note 1, at 30,837-41; Cable Fairness Inquiry, supra note 1, at m.91 & Id. 5 60.doc Doctrine Applied to New Technologies That the Commission’s decision in the current proceeding may be fore-ordained is not surprising, given how it has applied the Fairness Doctrine to a variety of new electronic media. The FCC’s approach to these media clearly reflects its growing skepticism toward the Fairness Doctrine. With respect to cable television, the FCC has said that cable’s lack of use of the “scarce” spectrum was not a bar to application of the doctrine. However, it applied the doctrine only to certain cable channels. To protect the public interest, the FCC requires cable operators to comply with the Fairness Doctrine only for channels over which they retain editorial control (thereby excluding public access channels and retransmitted broadcast signals).18 Allowing cable operators to surround retransmitted broadcast signals with channels of biased and unfair programming would, according to the FCC, “destroy the signals’ integrity and defeat the purposes” of the Fairness Doctrine.19 So few cable channels are now programmed by cable operators that the doctrine’s application to cable has raised much less furor than in the broadcast arena. Nonetheless, concurrently with its review of the Fairness Doctrine as applied to broadcasters, the Commission is also considering a repeal of the doctrine as it applies to cable television.20 When the Commission authorized direct broadcast satellite (DBS) service, a technology for distributing programming from satellites directly to subscribers, it declared that the Fairness Doctrine would apply only where the DBS operator acted like a broadcaster — programming its own channels. Where it acted like a common carrier, allowing third parties to distribute programming to subscribers on a first-come, firstserved basis, there would be no Fairness Doctrine obligations.21 This decision, however, was recently overturned by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, which held that DBS operators are broadcasters and must be subjected to all broadcast regulations — including the Fairness Doctrine.22 The court did not believe that the Commission had the 18 See supra note 2. 19 See Amendment of Part 74, Subpart 8C, of the Commission’s Rules and Regulations Relative to Community Antenna Television Systems, 30 F.C.C. 2d 301, 220-21 (1999). 20 Cable Fairness Inquiry, supra note 1. 21 See Inquiry into the Development of Regulatory Policy in Regard to Direct Broadcast Satellites, 90 F.C.C. 2d 676 (1983). 22 National Ass’n of Broadcasters v. FCC, 740 F. 2d 1190 (D.C. Cir. 1994). 6 60.doc discretion to license a broadcast technology and then exempt it from certain statutory broadcast regulations. The most troublesome technology for the FCC has been teletext, which has been exempted from the Fairness Doctrine completely. Most often, teletext operates as a kind of electronic newspaper. For example, stories from The New York Times could be carried on teletext. If the Fairness Doctrine does not apply to The New York Times in print form, it would be difficult to find a rationale for applying it to the same information when it is transmitted electronically. Not surprisingly, then, the Commission avoided applying the doctrine to teletext because it was virtually indistinguishable from the print media.23 Analogously, and with respect to the use of cable channels used to transmit similar information, the Commission recently stated that it had neither the “desire” nor the “constitutional authority” to apply the Fairness Doctrine. It has, therefore, proposed to exempt such cable channels from fairness obligations.24 Constitutional Basis Undermined The decision to refrain from applying the doctrine to the new technologies is an outgrowth of the welter of new voice, data, and video outlets that are available to the public. This wealth of information from various sources, by its very existence, undermines the rationale for applying the Fairness Doctrine to only one of those technologies — broadcasting. Last July the Supreme Court noted in a footnote in FCC v. League of Women Voters, that scarcity was the constitutional predicate for the Fairness Doctrine.25 Thus, added the Court, if Congress or the FCC were to conclude that technological developments had altered the broadcast market so much, it might reconsider its holdings that the scarcity of spectrum justified government regulation of the electronic media. In the next footnote, Justice Brennan, for the Court, turned specifically to the Fairness Doctrine, saying that the Court would be “forced to reconsider” its decision in Red Lion Broadcasting — which, the Court said, affirmed the constitutionality of the 23 See Amendment of Parts 2, 73 and 76 of the Commission’s Rules to Authorize the Transmission of Teletext by TV Stations, 48 Fed. Reg. 27,054 (June 18, 1983), petitions for reconsideration granted on other grounds, 80 Fed. Reg. 4676 (Feb. 1, 1965). 24 See Cable Fairness Inquiry, supra note 1, at n.70. 25 — U.S. — 104 S. Ct. 3165, 3116 n.11 (1994). 7 60.doc Fairness Doctrine — if the FCC showed that the doctrine “has the effect of reducing rather than enhancing speech.”26 Although the League of Women Voters decision was not expressly directed at the Fairness Doctrine, it may well presage a judicial affirmance of any Commission determination that the doctrine frustrates speech and should, therefore, be abolished. If the Commission should reach this conclusion and eliminate the doctrine, it will be up to the courts to determine whether the agency had the statutory power or discretion to do so. In any event, the immediate fate of the Fairness Doctrine will be up to Congress. It is possible that Congress will acquiesce in the Commission’s decision; however, it may react vehemently and move swiftly and assertively to undertake a vigorous role in directing the future course of broadcast regulation. Ultimately, though, the Supreme Court may have the last word. As it suggested in the League of Women Voters decision, the Court may reconsider the constitutionality of the Fairness Doctrine in light of the current media marketplace. Should it do so, the controversy in Congress and at the FCC could simply be laying the groundwork for its decision. 26 Id. at 3117 n.12. 8 60.doc