Collocations and Colligations in Translation and Interpreting

advertisement

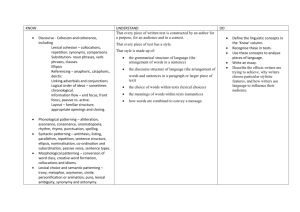

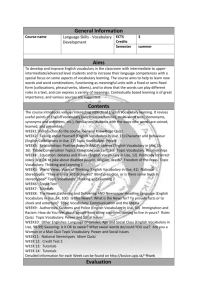

Collocations and Colligations in Translation and Interpreting Profesor universitar doctor Elena CROITORU Antonela DUMITRASCU (coautor) Universitatea « Dunărea de Jos » Galaţi 1. Lexis and grammar are interrelated and indisputably dependent on each other (Sinclair 1991, 1998). Thus, there is a close relationship between lexical strings and grammatical patterning. The language user will have to decide which of the meanings of the words or phrases are appropriate to a certain grammatical statement. As J. Sinclair puts it, “a grammar is a grammar of meanings not of words” (Sinclair 2004:18). In this perspective, collocability refers to sharing meanings between words and between phrases, collocations being the result. In other words, the underlying principle of word selection is that of collocation, according to which the choice of one word conditions the choice of the next, etc. Consequently, the patterning of words includes everything from collocations, through J. R. Firth’s colligations, to the conditioned probability of grammatical choices (id., ibid.). 1.1. Collocations are the systematic co-occurence patterns of a target word with other words (Biber et al. 1998:6; Jantunen 2004:14). The adjacent words around target words are called collocates (Firth 1968; Sinclair 1991). According to J. Sinclair (1991:17), collocations are the recurrent co-occurrences that a word has with its collocates within a given distance of each other (that is a “short space” between a target word, called node, and its collocates) measured in words. Others, Kjellmer (1987), Kennedy (1991), Mauranen (2000), Sinclair (2004) included, define collocations according to the number of occurrences of a lexical combination. However, the difference between collocations and lexical patterns is that the latter have pragmatic and/or discourse functions, whereas the former the former do not have such functions in themselves. They may be associations made by the writer, i.e. restricted or marked collocations in literary prose or in poetry. The fact must be mentioned that the use of collocations seems to be the weakest point of a non-native speaker. This aspect will help a native speaker of the target language (TL) “catch” a non-native translator. Furthermore, the odd collocations “created” by the translator under the source text (ST) influence will be interpreted as unusual collocations in their mother tongue. 1.2. Colligations are defined as co-occurrences between node words and grammatical classes, or as interrelations of grammatical categories, which concern categories such as word classes and sentence classes (Firth 1968:188; Tognini Bonelli 1996:74). A colligation is also an association of a word, “seen as a unique lexical item rather than as a member of its class” (Tognini Bonelli ibid.), with grammatical categories (Hoey 1997:8; Sinclair 1998:15) or with a particular position in a sentence or text (Hoey ibid.; Kennedy 1991:21). The linguistic factors concern lexical and grammatical associations, which also determine and impose constraints on the use of words. 1.3. The most frequent collocations are the nominal collocations built up by means of partitives such as a bar/piece/slab/stick of chocolate → baton/bucată/tablă mare/baton de ciocolată, a lump/piece/slab/slice/wedge of cheese → bucată/calup/felie/triunghi de brânză, which have Romanian symmetrical combinations. Such collocations have similar colligational features, i.e. the node can be marked [U], as in the examples above, or [C], or can take pluralization as in: a clutch/group/web of companies → grup (mic)/reţea de companii. Most partitives express quantity: e.g. a bit/great deal/(big) load of trouble → un pic de/mult necaz/un noian de necazuri (note the dissimilarity consisting in TL pluralization). Although the surface structure may give the impression of synonymy, translation errors may be due to missing the increase or decrease in the meaning intensity: e.g. a hint of trouble → un semn/indiciu despre apariţia unui necaz; a sniff of trouble → semn/indiciu mic despre apariţia unei probleme. Frequent errors are made in mistaking them for a scent of trouble → presimţirea necazului/intuirea apariţiei unei probleme. Most nominal collocations (N+of+N) are to a certain extent horizontal, symmetrical collocations, i.e. similar to the Romanian one: e.g. a school of thought → şcoală/curent de gândire, clarity/depth/freedom of thought → limpezimea/profunzimea/libertatea gândirii (N + genitive N). The collocational and colligational features of most combinations may be labelled nominal and prepositional: e.g. a strong stand against the enemy → o puternică rezistenţă împotriva inamicului. The preposition may change the meaning of both nominal and verbal collocations: (have) a feel for → (a avea) aptitudine pentru, have a feel for (the cloth) → a pipăi materialul. The meaning of the verb feel in collocations may shift from a verb of mental activity to a verb of perception in the verb+adverb collocations: e.g. feel keenly/strongly/deeply → a crede cu toaă tăria, feel dimly/vaguely → a simţi vag. 1.4. In collocations derived from current usage, the meaning interpretation is based on the “core” meanings of the two words: e.g. to be true to one’s word → a fi credincios cuvântului dat/aşi ţine cuvântul, whereas with the idiomatic ones, there is no such interpretation, but metaphorical extension is to be made: e.g. be true to one’s salt → a-şi sluji cu credinţă/devotament stăpânul, which also marks a change from collocation to colligation by the to-dative that is different from the temporal to in be true to the last → a nu-şi dezminţi niciodată loialitatea/devotamentul. Nominal collocations such as true feelings, true nature may be considered common ones not idiomatic like ill-feelings → resentiment, true bill → verdict de punere sub acuzare, true love → iubit, ibovnic, amant, or true penny (fig) → om dintr-o bucată/băiat de zahăr. The dictionary meaning of true is “genuine, real, authentic”. There may be contextual strong colligation with a possessive adjective (his true feelings/nature), or with of-genitive (the true feelings/nature of), or with a verb such as disguise, deny, hide, mask with a semantic preference of reluctance. The semantic preference of feel/feeling is that of “expression” which is prevailing. Therefore, the semantic preference controls the collocational and colligational patterns. With the nominal collocations, the adjective can turn a collocation from a common one, derived from current usage, into a marked, restricted one. For example, the adjective sneering will make the collocation sneering response a marked one. The translator will seek an adjective in the semantic field of “unpleasant”, with variants such as “sharp, grumpy, impudent”. Every Romanian equivalent will miss the very unpleasant element of scorn and insult in sneer, which will lead to a downtoning effect on the TT. The aspect mentioned above about collocations as the weak point of a non-native translator may hold valid about the syntactic features: a structure-preserving translation may or may not lead to an ungrammatical or unacceptable sentence in Romanian. 2. Translation strategies are often mistaken for some techniques used by a professional to give an “improved” or “incremental” TL version using clues emerging from inference, or from either knowledge, or from his linguistic skill, just “to fall on his feet”, which R. Setton (1994) calls syntacrobatics. In Setton’s (1999), opinion, this will often entail deviations from the ST grammatical structures and lexical combinations, as well as dilutions of meaning which experts usually correct discreetly. He insists on this idea as regards simultaneous interpreting (SI) and considers the interpreting task to be a combination of the following sub-skills and competences: a) comprehension of the SL at all levels (including pragmatic clues); b) context-acquisition, off and on line: preparation, awareness, alertness; c) metarepresentation, or empathy and acting; d) syntactic agility and a rich vocabulary in the TL. We would suggest two further competences: collocational and colligational competences, i.e. a good command of the combining capacity of words in the TL and the ability to use them in TL correct grammatical structures and constructions. 2.1. Both the translator and the interpreter need the capacity of clarifying text-specific sources of difficulty by controlling other variables that are considered factors in performance. Such variables may be: The translator’s (interpreter’s) linguistic competence and cognitive experience for the decoding and encoding phases of comprehension and production; Collocational and colligational competences both in the language for general purposes (LGP) and in the language for special purposes (LSP); The translator’s (interpreter’s) capacity of giving accurate and adequate representations in the TL, which depends on the properties of the discourse and on his/her background knowledge. 2.2. In case of SI, the interpreter’s ease of recognizing and retrieving combinations of words and grammatical structures and of quickly rendering them in the TL should be considered. In addition, external factors (like acoustics and visibility), which affect perception, and reduce contextual clues, are also factors of performance. 2.3. In translating and interpreting collocations and colligations, we would suggest two strategies: the form-based strategy and the meaning-based strategy. The form-based strategy, which is used with the structural, horizontal, parallel, or symmetrical combinations, consists in a more or less direct rendering of the ST collocations and colligations by corresponding combinations and grammatical structures in the TL. The meaningbased strategy, which is conceptual, vertical, non-symmetrical, consists in producing TL combinations and structures only on the basis of a conceptual representation of the ST meaning. This holds valid especially with the non-equivalence situations, where there are no equivalents with the same structure in the TL. The two strategies differ from each other both in term of the underlying cognitive processes and in terms of the final product, i.e. the TT. In term of process, the meaning-based strategy involves processing at a deeper semantic level (Gernsbacher and Schlesinger 1997:123; Lonsdale 1997:96), whereas the form-based strategy involves processing at a surface level. In terms of the final product, by using the former, The TT will have a lexical and morpho-syntactic form different from that of the ST, whereas by using the latter, the TT will be formally similar to the ST. 2.4. Generally, the procedure involved in form-based (simultaneous) interpreting is frequently called transcoding, whereas the one involved in meaning-based interpreting is considered to be a process of deverbalization. Interpreters choose either the meaning-based strategy or the form-based one function of the difficulty of collocations and colligations, as well as function of the specificity of the interpreting situation. As H. V. Dam puts it, “the more difficult the source text, the more the interpreter tends to deviate from the meaning-based approach and to interpret on the basis of source text form” (Dam 2001:29). However, interpreters consider the meaning-based interpreting to be the standard strategy. Most often, the form-based strategy is made use of with technical terms, in general, and with the collocations whose component elements are technical words, in particular. These may be real sources of translation and interpreting difficulties. 3. Both in translation and interpreting, focus is laid on ST patterns recognition and TT patterns retrieval within the decoding and encoding phases. 3.1. Figure 1 makes it obvious that the box including the cognitive processes is superimposed on the box including the language aspects, and that the cognitive processes influence the translating and interpreting strategies: Language Grammar ↓ Colligation Collocation recognition recognition ↓ → Lexicon ↓ Decoding ↓ ← ↓ Higher cognitive functions and processes The speaker’s (interpreter’s) knowledge and cognitive experience ↓ Comprehension Categorization Pattern-matching Reasoning and decision-making Deduction – inference, representation Metarepresentation of shared meaning Negotiation of meaning ↓ Encoding ↓ ↓ Form-based strategy Meaning-based strategy ↓ ↓ Word-for-word translation Reconceptualizing strategy ↓ ↓ Parallel, symmetrical Conceptual, nonsymmetrical combinations and structures combinations and structures Linguistic and cognitive processes in translating and interpreting collocations and colligations metarepresentation of shared meaning in SI: S(peaker), and A(ddressee) through I(nterpreter). There is interaction between linguistic and higher cognitive processes. For example, metarepresentation as a higher cognitive function allows for the representation of abstract and hypothetical events or states of affairs called irrealis. The linguistic expressions of the irrealis dimansion are negation, epistemic and deontic modalities in modal verbs, phrases and idioms, conditional, subjunctive and verb tenses. Therefore, metarepresentation and language are thoroughly interrelated. “In addition to the lexical and syntactic equipment to formulate simple firstorder statements and descriptions of state of affairs, all human languages comprise devices to communicate degrees of reality, possibility, probability, and desirability or to attribute elements or descriptions to another source”, as Setton mentions (Setton 2001:13). Furthermore, even with texts having a simple syntax, many errors are made in expressing possible, hypothetical, and conditional events or facts (irrealis). Moreover, a lot of mistakes are registered in correlating the right modality with the right facticity (hypothesis vs fact), and even more with implicit negation: more or less is negated as compared to the original. 3.2. Experienced translators and interpreters usually develop some strategies which are to a certain extent internalized, based on recognition of recurrent patterns and combinations. However, since lexical choice always needs some resources, it cannot be automatic. Besides, “odd” collocations and wrong grammatical structures, as well as an awkward discourse structure will make the native “catch” a non-native translator/interpreter. 3.3. The context, the syntactic complexity (e.g. embedded clauses), the lexical combinations and, in the TT, the lexical retrieval in the appropriate style and register, the discourse structure and the grammatical sequencing are essential elements in the decoding processes as it is obvious in the following table: Language knowledge and language use context situation collocations discourse structure grammatical structures and sequencing/ colligations embedded clauses referential cohesion connectors word order Decoding processes Semantics - reference assignment - disambiguation - conceptual enrichment pragmatics pragmatics Translating and interpreting strategy form-based strategy meaning-based strategy (using the intentionality in the words,in negotiating the meaning of collocations) form-based strategy (avoiding morpho-syntactic inference from the SL) meaning-based strategy (using syntax to provide information) form-based strategy Language, decoding processes and translating strategies The table above may offer a proper grounding in syntax, semantics and pragmatics in applying the translating strategies to collocations and colligations. With interpreters, especially in SI, automacity is to be considered with its three degrees: automatic, automatable and controlled/strategic (Setton 2001:7). A complex task is expected to include elements of all three. This is the first important input in SI. The intentionality in the words, in negotiating the meaning of collocations, the resistance to the language interference, and the knowledge of the TL norms in terms of grammar and collocability are very important in translation. Moreover, satisfactory pragmatic processing depends on the correct interpretation of collocations and colligations, and on the inputs at the semantic level (basic word meanings, context). With the non-symmetrical combinations and structures, the decoding processes may go from reference assignment, through disambiguation, to conceptual enrichment, function of the translational context and interpreting situation. However, deviations and dilutions may occur which need to be corrected. Therefore, adjustments of context may be possible before achieving an equilibrium which meets the “expectations” of relevance. 3.4. As far as the form-based strategy is concerned, the fact must be mentioned that a wordby-word rendering can be misleading and may result in a “pragmatic failure”, i.e. the inability to understand what is meant by what is said. In addition, word-to-word transcoding may not always be appropriate, sometimes even entirely inappropriate. The Paris school recommendation is to “strive always to reformulate, and with the exception of some technical terms, be wary of ‘equivalents’” (Marslen-Wilson and Welsh 1978). Consequently, after reading and comprehension, with the other steps of the translating process, and after listening to the speech in interpreting, respectively, the conceptual/linguistic processing of both collocations and grammatical structures is decisive for the final product. 4. An experiment was made to study some aspects of translating collocations and colligations. Six fragments from Henry James’ novel What Maisie Knew and Joseph Conrad’s Typhoon belonging to different levels of difficulty were selected for analysis. Space will allow for only two of them (see Appendix). The basic method was a comparative one. Thus, a comparative analysis of the ST and the TT was made, focus being laid on the similarities and dissimilarities of such combinations and structures to identify the translating strategies, associated with the notion of difficulty. The subjects were 24 participants in the “Translation and interpreting” master programme at the “Dunărea de Jos” University of Galaţi. The major tasks were to identify the collocations and colligations in the texts and distinguish between the form-based and meaning-based translation strategies. Such sub-skills as pattern recognition and lexical retrieval in the decoding and encoding phases were allocated very much attention. The subjects were requested to pay special attention to such cognitive processes as comprehension, pattern-matching and metarepresentation. Considering the cognitive process of reasoning, they were required to bring forward arguments for their final choices. The students and I also agreed to make this process a “think-aloud” method. Thus, the decion-making phase was widely debated, especially within the reconceptualizing strategy. The findings were quite interesting. Firstly, the allocation of attention to (a) certain process(es) or subskill(s) may lead to much more reliable results. Secondly, in translating difficult texts, or at least difficult combinations and structures, the form-based strategy is used. Thirdly, it was 70% of the subjects that identified the collocations and colligations in the texts, but only 40% could distinguish between the two translation strategies. Less than 40% were able to point out the dissimilarities and argue about them. The conclusion may be drawn that more attention needs to be paid to such combinations both in teaching translation syllabus and in translator training, considering the great differences between English and Romanian, on the one hand, and the fact that it is collocability that is decisive in “catching” a non-native translator into English, on the other. Thus, besides the need for some further dictionary of collocations, besides the two already published, i.e. Dicţionar de colocaţii nominale englez-român (Pârlog and Teleagă, coord. 1999), and Dicţionar englez-român de colocaţii verbale (Pârlog and Teleagă, coord. 2000), special attention should be paid to such combinations during the translation lectures, seminars and practical courses. Furthermore, evidence is obvious for the superiority of a qualified and competent translation and interpreting training, as a component task, followed by integration, over the simple “practice makes perfect training”. Appendix This was odd justice in the eyes of those who still blinked in the fierce light projected from the tribunal […] → Acest mod de a face dreptate părea ciudat în ochii celor care încă mai clipeau orbiţi de lumina necruţătoare ce venea dinspre tribunal […] (H. James, What Maisie Knew) Her lurches had an appalling helplessness […] → Zbuciumul lui [vasului] dovedea o neputinţă înspăimântătoare […] The gale howled and scuffed about gigantically in the darkness […]. At certain moments the air streamed against the ship as if sucked through a tunnel with a concentrated solid force of impact […] → Vântul puternic urla şi bătea năprasnic în beznă […]. În răstimpuri, curenţii de aer loveau vasul de parcă l-ar fi tras în jos printr-o pâlnie uriaşă cu o cumplită forţă de impact care izbea vasul cu înverşunare […] And again he heard that voice […] with a penetrating effect of quietness in the enormous discord of noises, as if sent out from some remote spot of peace beyond the black wastes of gale; again he heard a man’s voice – the frail and indomitable sound that can be made to carry an infinity of thought, resolution and purpose […] → Şi din nou auzi glasul acela slab […] cu un puternic efect liniştitor în vacarmul acela asurzitor, venind parcă din vreun loc îndepărtat, dintr-o oază de pace de dincolo de rafalele ce se năpusteau din întuneric; din nou auzi glasul unui bărbat – vocea fragilă dar stăruitoare ce e în stare să exprime o infinitate de gânduri, hotărâri şi speranţe […] (J. Conrad, Typhoon) REFERENCES Biber, D. Et al. (1998). Corpus Linguistics: Investigating Language Structure and Use, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Croitoru, E. (2004). English Through Translations, Galaţi: Editura Fundaţiei Universitare ”Dunărea de Jos”. Dam, H. (2001). “On the option between form-based and meaning-based interpreting: the effect of source text difficulty on lexical target text form in simultaneous interpreting”, in The Interpreters’ Newsletter, Università degli Studi di Trieste, Scuola Superiore di Lingue Modernii per Interpreti e Traduttori, No. 11, pp. 27-54. Firth, J. R. (1968). “A synopsis of linguistic theory 1930-1955”, in F. R. Palmer (ed.), Selected Papers of J. R. Firth 1952-1959, pp. 168-205, London: Longman. Gernsbacher, M. A. and Schlesinger, M. (1997). “The proposed role of suppression in simultaneous interpretation”, in Interpreting 2 (1-2), pp. 119-140. Hoey, M. (1997). “From concordance to text structure: new uses for computer corpora”, in P. Melia and B. Lewandowska-Tomaszczyk (eds.), Proceedings of the Practical Application of Linguistic Corpora Conference, pp. 2-23, Poland: Lodz University Press. Jantunen, J. H. (2004). “Untypical patterns in translations”, in A. Mauranen and P. Kujamäki (eds.), Translation Universals, Amsterdam-Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 101-126. Kennedy, G. (1991). “Between and through: The company they keep and the functions they serve”, in K. Aijmer and B. Altenberg (eds.), English Corpus Linguistics. Studies in Honour of Jan Svartvik, pp. 95-110, London and New York: Longman. Kjellmer, G. (1987). “Aspects of English Collocations”, in W. Meijs (ed.), Corpus Linguistics and Beyond. Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on English Language Research on Computerized Corpora, pp. 133-140, Amsterdam: Rodopi. Lonsdale, D. (1997). “Modelling cognition in SI: Methodological issues”, in Interpreting 2 (1-2), pp. 91-117. Marslen-Wilson, W. and Welsh, A. (1978). “Processing interactions during word recognition in continuous speech”, in Cognitive Psychology 10, pp. 29-63. Mauranen, A. (2000). “Strange strings in translated language: A study on corpora”, in M. Olohan (ed.), Intercultural Faultlines. Research Models in Translation Studies 1. Textual and Cognitive Aspects, pp. 119-141, Manchester and Northampton: St. Jerome Publishing. Pârlog, H. And Teleagă, M. (coord.). (1999). Dicţionar de colocaţii nominale englez-român, Timişoara: Editura Mirton. Pârlog, H. And Teleagă, M. (coord.). (2000). Dicţionar englez-român de colocaţii verbale, Iaşi: Editura Polirom. Setton, R. (1994). “Experiments in the application of discourse strategies to interpreter training”, in C. Dollerup and A. Lindegaard, Teaching Translating and Interpreting 2: Insights, Aims, Visions, pp. 183-198, Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins. Setton, R. (1994). A Cognitive-Pragmatic Analysis of Simultaneous Interpretation, Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins. Setton, R. (2001). “Deconstructing SI: a contribution to the debate on component processes”, in The Interpreters’ Newsletter, Università degli Studi di Trieste, Scuola Superiore di Lingue Modernii per Interpreti e Traduttori, No. 11, pp. 1-26. Sinclair, J. (1991). Corpus, Concordance, Collocation, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Sinclair, J. (1998). “The lexical item”, in E. Weigand (ed.), Contrastive Lexical Semantics, pp. 1-24, Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins. Sinclair, J. (2004). Trust the Text. Language, Corpus and Discourse, London: Routledge. Tognini Bonelli, E. (1996). Corpus Theory and Pracitce, TWC.