ISS research paper template

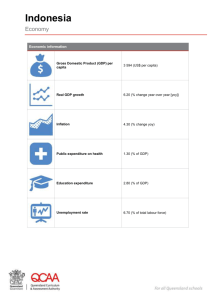

advertisement