Notes - Nature

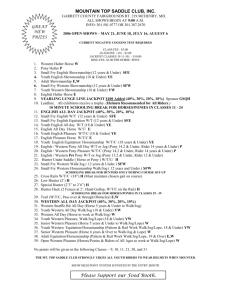

advertisement

Horse performance and the history of express postal systems (540 BCE – 1861 AD). Supplementary information Notes i. HISTORICAL SOURCES: Persian Empire - Xenophon, Cyropaedia, Book VIII, 6.17-18, and Herodotus, Histories, Book V, Terpsichore 5.52-53; China - des Rotours, R. Traité des fonctionnaires et Traité de l’armée, (Chap.XLVI, du Xingtangshu), Brill, Leiden, tome 1, p. 111 (1947); Mongol Empire - D’Ohsson, Histoire des Mongols, Van Cleef, vol IV, p. 402403 (1834); Mamelouk Sultanate - Sauvaget, J. La Poste aux Chevaux dans l’Empire des Mamelouks, A. Maisonneuve, Paris, (1941); Italy - Fedele, C. & Gallenga, M. Per Servizio di Nostro Signore, Mucchi Editore, Prato, p. 53 (1988) and Dallmeier, M. Il casato principesco dei Thurn und Taxis e le poste in Europa (1490-1806). In: Le Poste dei Tasso, un’Impresa in Europa, Comune di Bergamo ed., Bergamo Italy (1984); France - Vaillé, E. Histoire Generale des Postes Francaises, PUF, Paris, tome 2, p. 26 (1947); North America www.xphomestation.com/facts.html. ii. HISTORICAL INFORMATION. One of the most remarkable feats in the history of express postal system is William Cody’s (Buffalo Bill) ride as an Overland Pony Express employee when he was only 14 years old. Due to a killed relay rider and other troubles on the route, he rode from Red Buttes Station to Rocky Ridge Station and back, a distance of 518 km, in 21 hours and 40 minutes, at an average speed of 24 km/h. William Cody used 22 horses (thus he passed through 21 ‘swing’ stations). 1 From the number of horses utilized and the scheduled delivery time, it can be calculated that in Overland Pony Express horses rested for about 3 days between successive runs. We know today (Snow D. H. et al. In: Equine Exercise Physiology 2, Gillespie J. R. and Robinson N. E. (eds), Davies CA, ICEEP Publications p 701-710, 1987) that a low energy diet (hay used at that time) is associated to glycogen replenishment, after a race, lasting 2-3 days. A modern diet can do that in 24 hours. iii. RIDERS’ PERFORMANCE. The endurance capability of riders can be addressed by analysing the data from the Overland Pony Express (1860-1861), the most recent and documented horse-based mail system. Riders aged 22.8 ± 6.0 years, with a mass of about 50 kg, could rely (Armstrong and Welsman, Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 22, 435, 1994) on a maximum metabolic power ( VÝO2,MAX ) of 3.2 LO2/min. When galloping normally or ‘in suspension’, the metabolic power of riding (Devienne and Guezennec, Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 82, 499-503, 2000) ranges from 1.9 to 2.4 LO2/min, respectively, the average corresponding to 66.4% of VÝO2,MAX . That fraction of the maximum aerobic power can be sustained for up to 276 minutes (Saltin, in: Limiting Factors of Physical Performance. J. Keul Ed., Georg Thieme, Stuttgard, 235-252, 1973) which, at a horse speed of 20 km/h, is equivalent to 92 km, or 4-5 stations. Thus, we conclude that riders’ performance was limited by their aerobic capacity. iv. PHYSIOLOGICAL REMARKS. Horses’ cardiac rate has a scope from 25-30 to 260 beats per minute and their body mass is 55% made by muscles. This implies a high specific VÝO2,MAX even without the blood boost caused by the spleen emptying, which contributes, when operating, a maximum specific metabolic power twice as much as in humans. Also, the lactic acid concentration can reach a maximum of about 20-30 mM/L, 2 The horse is the largest athletic species in mammals and, because of the high specialization for speed, is penalized during endurance events. Apart from the extreme design of the musculo-skeletal system (the mechanical internal work needed to accelerate limbs is kept to a minimum – Minetti J. Biomech. 31 (5): 463-468, 1998), which is prone to wear and damage in very long journeys, the main limitation is the cooling capacity with respect to the massive heat generation. The fact that larger animals show better thermal insulation because of the unbalanced ratio between heat conductance and surface area (Schmidt-Nielsen, Scaling: why is animal size so important? Cambridge University Press 1984) is a disadvantage for the athletic horse. Autologous blood transfusion in humans elevates VÝO2,MAX of 12.8% when the hematocrit (Ht) changes from 43 to 55 % (Robertson, J. Appl. Physiol. 53: 490, 1982). The self blood produce a more substantial boost in the doping in horses (Ht from 40 to >65%) could maximum aerobic power (about 25-30%). Horse maximum aerobic power has been shown to be dependent on exercise Ht (Kearns et al. Equine Vet J Suppl. 34: 485-90, 2002). In order to discourage blood doping and to preserve athletes’ health, the International Cycling Union and the International Ski Federation introduced an upper limit of 50% for Ht (Ashenden, Haematologica 87 (3): 225-234, 2002; Kazlauskas et al. Clin. J. Sports Med. 12 (4): 229-235, 2002) above which athletes are disqualified. Long term gallop induces hyperthermia in horse tendons, with risks of degenerative lesions (Wilson and Goodship, J. Biomech. 27(7): 899-905, 1994). While only 5-10% of the stored elastic energy is dissipated by (in vitro) tendons (Ker, Dimery and Alexander, J. Zool. 208: 417-428, 1986), the absolute amount of energy is such that a consistent quantity of heat is 3 generated. While further research is needed, it seems that a threshold speed for gallop could be associated to a threatening departure from a thermal stability of the tendon core. Top performance in horse locomotion resembles the response of a turbo charged car where the cooling fluid has been removed or become very dense and viscous. Starting a cold engine, high speeds using most of the available power (turbo charge) can be sustained for short distances. The hotter the engine, the slower the speed, in order to cope with the impaired cooling system (no turbo charge). A long journey in those conditions can be sustained if the generated motion allows the necessary passive air cooling. Further details are available at www.cheshire.mmu.ac.uk/exspsci/research/biomex/Minetti.htm and at www.cheshire.mmu.ac.uk/exspsci/research/biomex/biomres1.htm 4