Social functions of emotions

advertisement

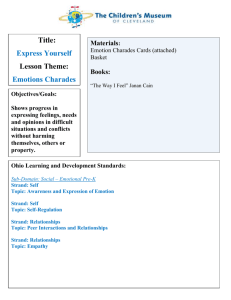

Social Functions 1 Social Functions of Emotions Dacher Keltner University of California-Berkeley Jonathan Haidt University of Virginia [Full reference: Keltner, D., & Haidt, J. (2001). Social functions of emotions. In T. Mayne & G. A. Bonanno (Eds.), Emotions: Current issues and future directions. New York: Guilford Press. (pp. 192-213).] Please address correspondence to: Dr. Dacher Keltner, Department of Psychology, 3210 Tolman Hall, University of California, Berkeley CA, 94720. Internet: keltner@socrates.berkeley.edu. Social Functions 2 Social Functions of Emotions The primary function of emotion is to mobilize the organism to deal quickly with important interpersonal encounters (Ekman, 1992, p.171). Emotions are a primary idiom for defining and negotiating social relations of the self in a moral order (Lutz & White, 1986, p.417). Emotion theorists disagree in many ways, but most share the assumption that emotions help humans solve many of the basic problems of social living. For evolutionary theorists, emotions are universal, hard-wired affect programs that solve ancient, recurrent threats to survival (Ekman, 1992; Lazarus, 1991; Plutchik, 1980; Tomkins, 1984; Tooby & Cosmides, 1990). For social constructivists, emotions are socially learned responses constructed in the process of social discourse according to culturally specific concerns about identity, morality, and social structure (Averill, 1980; Lutz & White, 1986). These contrasting approaches conceive of the defining elements, origins, and study of emotions in strikingly different ways, but both ascribe social functions to emotion. In this chapter we present a social-functional account of emotions that attempts to integrate the relevant insights of evolutionary and social constructivist theorists. Our account can be summarized in three statements: 1) Social living presents social animals, including humans, with problems whose solutions are critical for individual survival; 2) Emotions have been designed in the course of evolution to solve these problems; 3) In humans, culture loosens the linkages between emotions and problems so that cultures find new ways to solve the problems for which emotions evolved, and cultures find new ways of using emotions. In the first half of the chapter we synthesize the positions of diverse theorists in a taxonomy of problems of social living, and then consider how evolution-based, primordial emotions solve those problems by coordinating social interactions. In the second half of the chapter we discuss the specific processes according to which culture transforms primordial emotions, and how culturally shaped, elaborated emotions help solve the problems of social living. Primordial Emotion Evolutionary theorists concern themselves with universal, biologically based, genetically encoded emotion-related patterns of appraisals and responses observed across species and cultures, which we will refer to as primordial emotions. Primordial emotions are shaped by evolutionary forces, genetically encoded, embedded in the human psyche, linked to biological maturation, and they involve coordinated physiological, perceptual, communicative, and behavioral processes that are meant to produce specific changes in the environment. They occur most typically within the context of immediate face-to-face interactions, and they are brief, lasting seconds to perhaps minutes, but not hours or days (Ekman, 1992). Although functional analyses have been a mainstay of evolutionary theorizing about emotion (e.g., Campos, Campos, & Barrett, 1989; Darwin, 1872; Izard, 1977; Plutchik, 1980), it is only recently that theorists have begun to systematically link specific emotions to social functions. This recent theoretical development can be attributed to several sources (Barrett & Social Functions 3 Campos, 1987). Advances in ethology and behavioral ecology have illuminated the specific advantages and problems posed by group living (Krebs & Davies, 1993). Working within different traditions, theorists have begun to characterize the connections between specific emotions and attachment (e.g., Kunce & Shaver, 1987), mate selection and protection (Buss, 1992), game theoretical characterizations of altruism, cooperation, competition, and interpersonal commitment (Frank, 1988; Nesse, 1990; Trivers, 1971), and dominance and submissiveness (e.g., Keltner & Buswell, 1997; Ohman, 1986). We believe these recent developments can be summarized in a social functional approach to emotion (Frijda & Mesquita, 1994; Keltner & Haidt, 1999; Keltner & Kring, 1998). Social functional accounts operate at multiple levels of analysis, specifying the social benefits emotions bring about for the individual, dyad, group, and culture. Across diverse methods and levels of analysis, social functional accounts share certain assumptions. Most notably, social functional accounts assume that group living, which has been characteristic of humans and other species for millions of years, confers many advantages over solitary living. These advantages include more proficient food gathering, responses to predation, and raising of offspring. Group living also creates new problems requiring the coordination of group members. To meet these problems and opportunities, humans have evolved a variety of complex systems. Each system is organized according to a specific goal (e.g., to protect offspring or maintain cooperative alliances) that is served by multiple subsystems. These include specific perceptual processes, higher order cognition, central and autonomic nervous system activity, as well behavioral responses, both intentional and reflex-like. For example, theorists have observed that humans form reproductive relationships with the help of an attachment system (e.g., Bowlby, 1969; Kunce & Shaver, 1987). The attachment system involves perceptual sensitivities to potential mates, representations of relationships, autonomic and hormonal activity related to affiliative, sexual, and intimate behavior, behavioral routines such as flirtation, courtship, and soothing, and specific emotions as we discuss below. Within each system, primordial emotions serve two general functions (see also JohnsonLaird & Oatley, 1992). First, primordial emotions signal that action is necessary, either because of a deviation from an ideal state of social relations, or because an opportunity presents itself. Primordial emotions therefore involve perceptual, appraisal, and experiential processes that monitor the conditions of ongoing relations, detecting disturbances (e.g., an infant’s distress) or opportunities (a potential mate). Once activated, emotion-related perception and experience interrupt ongoing cognitive processes and direct information processing to features of the social environment that allow for the restoration or establishment of desirable social relations (Clore, 1994; Lazarus, 1991; Lerner & Keltner, in press; Schwarz, 1990). Second, primordial emotions motivate behavior that establishes (or reestablishes) more ideal conditions of social relations. Primordial emotions involve autonomic, hormonal, and central nervous system activities that are tailored to specific social actions, such as fighting, copulating, offering comfort, and signaling dominance (Davidson, 1980, 1993; Frijda, 1986; Levenson, 1994; Le Doux, 1996; Porges, 1995; Sapolsky, 1989). Primordial emotions also involve vocal, facial, and postural communication that: provide quick and reliably identified information to others (Ekman, 1984, 1993; Izard, 1977; Scherer, 1986), which shapes social interactions as we detail in a section that follows. We now consider how different emotions might help solve the different problems of group living. Social Functions 4 The Problems of Group Living and Primordial Emotions Functional accounts begin with an analysis of the problems emotions were presumably designed to solve, either by evolution or cultural construction (Keltner & Gross, 1999). Our review of the theorizing on the social functions of emotion identifies three classes of problems related to group living to which emotions are intimately linked, and we would argue, have been designed to solve. Table 1 summarizes the nature of these problems, the general systems that have evolved to meet these problems, as well as related emotions and their specific functions. We note that Table 1 does not include all states we consider emotions (e.g., amusement does not fit neatly into the taxonomy); rather it lists the emotions that seem well suited to solving specific social problems. Additionally, although Table 1 describes how emotions are linked to prototypical social objects (e.g., sympathy for vulnerable family members), we believe emotions generalize to related social objects (e.g., sympathy for downtrodden members of society). Several theorists have commented on the flexibility of the associations between emotions and their intentional objects (e.g., Tomkins, 1984), which we discuss in an ensuing section. The problems of Physical Survival First, individuals must solve the problems of physical survival, including avoiding death by predation, violence, and disease. Fear is the primordial emotion at the heart of the “fightflight” system (Ohman, 1986), which helps individuals avoid death by predation or other physical attacks. Much is understood about the physiology of fear (LeDoux, 1996). On the appraisal side, the amygdala contains specialized areas that scan incoming sensory information for patterns that have been associated with danger. The amygdala can trigger a fear response even before the incoming information has been sent to the occipital cortex for full processing, and even before an individual knows what an object is (LeDoux, 1996; see chapter XX for further elaboration). On the output side, primordial fear involves triggering the hypothalamicpituitary-adrenocortical axis, which pumps a quick dose of cortisol and other stress hormones into the bloodstream, to ready the organism for fight or for flight. Primordial fear can be seen as the heart of a system that includes a variety of cognitive and behavioral mechanisms that make it more effective, e.g., vicarious learning, and the preparedness of animal phobias (Mineka & Cook, 1988). Disgust can similarly be seen as the primordial emotion at the heart of the “foodselection” system (Rozin, 1976b), which helps humans choose a balanced and safe diet. Unlike fear, disgust is not found in other animals; only a simpler precursor, distaste, can be seen in rats, and other generalist animals. Co-evolving with the tremendous expansion of cognitive ability in humans, the distaste response has expanded to become the disgust response (Rozin, Haidt & McCauley, in press). In humans, food rejections are not based primarily on the sensory properties of the object, but rather on a knowledge of what it is, or what it has touched (Rozin & Fallon, 1987). Potential foods elicit disgust if they resemble, or have come in contact with, certain powerful elicitors of disgust, such as feces and decaying animal bodies. The food selection system is further expanded by the addition of learning mechanisms, such as one-trial learning for nausea-inducing foods (Seligman, 1971), and by cultural mechanisms, such as cuisine, which marks prepared foods with a reassuringly familiar blend of spices or flavors (Rozin, 1996). The Problems of Reproduction Social Functions 5 Evolutionary and attachment theorists have speculated how a variety of emotions solve the problems of reproduction, which include procreation and the raising of offspring to the age of reproduction. The problems of finding and keeping a mate are in part met by emotions of romantic love and desire, which facilitate the identification, establishment, and maintenance of reproductive relations. These emotions involve appraisals, perceptions, and experiences that are sensitive to cues related to potential mate value. These include beauty, fertility, chastity, social status, and character (Buss, 1992; Ellis, 1992), expressive behaviors that signal interest and commitment (Frank, 1988) and evoke desire and love, and hormonal and autonomic responses that facilitate sexual behavior (Davidson, 1980). In table 1 we also contend that the experience and display of emotions related to the loss of a partner provoke succorance in others, and eventually helps individuals establish bonds with new mates. We label this emotion sadness (for similar analysis of distress, see Dunn, 1977; for analysis of grief, see Lazarus, 1991). The protection of potential mates from competitors is equally critical. Jealousy, the literature shows, relates to mate protection, and is triggered by cues that signal potential threats to the relationship, such as possible sexual or emotional involvement of the mate with others (Buss, 1992). Jealousy motivates possessive and threat behaviors that discourage competitors and prevent sexual opportunities for the mate (Wilson & Daly, 1996). Mammalian neonates are extremely dependent and vulnerable to predation, and continue to be so for much longer periods of time compared to other species. As a consequence, social species have evolved caregiving-related emotions of parental and child love and sympathy, which facilitate protective relations between parent and offspring (Bowlby, 1969; Kunce & Shaver, 1987). The caregiving system involves perceptions and experiences that sensitize parents to infantile cues (e.g., of neotany, distress) and infants to vocal and visual cues of parenthood (Fernald, 1992). Filial love and sympathy are characterized by experiences and expressive behavior such as mutual smiles and gaze patterns. These are elements of interactions that strengthen loving bonds, and physiological responses that help caretakers respond to others’ distress (e.g., Eisenberg, et al., 1989). The Problems of Group Governance Finally, theorists have argued that emotions help solve two subclasses of problems related to group governance, which arise in several contexts, including the allocation of resources and distribution of work (Fiske, 1991). First, to avoid the problems of cheating and defection and to encourage cooperation, in particular among non-kin, humans reciprocate cooperative and non-cooperative acts towards one another (Trivers, 1971). Reciprocity is a universal social norm (Gouldner, 1960), and is evident in gift giving, eye-for-an-eye punishment, quid-pro-quo behavior in other species (de Waal, 1996), and the tit-for-tat strategy (Axelrod, 1984). Several emotions signal when reciprocity has been violated and motivate reparative behavior (de Waal, 1996; Frank, 1988; Nesse, 1990; Trivers, 1971). Guilt occurs following violations of reciprocity and is expressed in apologetic, remedial behavior that re-establishes reciprocity (Keltner & Buswell, 1996; Tangney, 1991). Moral anger motivates the punishment of individuals who have violated rules of reciprocity, and is defined by the sensitivity to issues of justice and unfairness (Keltner et al., 1993). Gratitude at others’ altruistic acts is a reward for adherence to the contract of reciprocity (Trivers, 1971). Envy motivates individuals to derogate others whose favorable status is unjustified, thus preserving equal relations (Fiske, 1991). Second, humans must solve the problem of group organization. Status hierarchies Social Functions 6 provide heuristic solutions to the problems of distributing resources, such as mates, food, and social attention, and the labor required of collective endeavors (Fiske, 1990; de Waal, 1986, 1988). Hierarchies are dynamic processes, and require continual negotiation and redefinition. The establishment, maintenance, and preservation of status hierarchies is in part accomplished by emotions related to dominance and submission (de Waal, 1996; Ohman, 1986). Embarrassment and shame appease dominant individuals and signal submissiveness (Keltner & Buswell, 1996; Miller & Leary, 1992), whereas contempt is defined by feelings of superiority and dominance vis-a-vis inferior others. Awe tends to be associated with the experience of being in the presence of an entity greater than the self (Keltner & Loew, 1996). In some cases, awe is elicited by nature or art (Shin, Keltner, Shiota, & Haidt, 2000). In other instances, awe is elicited by the presence of higher status others, and thereby endows higher status individuals with respect and authority (Fiske, 1991; Weber, 1957). Primordial emotions and social interaction We believe that emotions most typically solve the problems of social living in the context of ongoing face to face interactions (e.g., Frijda & Mesquita, 1994; Keltner & Kring, 1998). This view has typically been espoused by those who argue that emotions are constructed within social relationships, and by implication, are not biologically based or universal (e.g., Lutz & Abu-Lughod, 1991). Evolutionary theorists, however, have long suggested that humans evolved adaptive responses to the emotional responses of others (e.g., Darwin, 1872; Ohman & Dimberg, 1978), consistent with the claim that communicative behavior of senders and receivers coevolved (Eibl-Eibesfeldt, 1989; Hauser, 1996). From this perspective, one individual's emotional expression serves as a "social affordance" which evokes "prepared" responses in others. Primordial emotions structure social interactions in at least three ways. First, emotional displays evoke complementary emotional responses in others (for more complete review, see Keltner & Kring, 1998). These complementary emotions are core elements of interactions such as courtship, bonding, appeasement, and reconciliation (Eibl-Eibesfeldt, 1989). Thus, soothing interactions involve sympathetic responses to another’s distress. Some socialization interactions involve angry responses to another’s transgression, followed by a shamed or guilty response to the anger (Ausubel, 1955; Gibbard, 1990). Appeasement interactions involve displays of submissive emotions, such as embarrassment and shame, that evoke reconciliation related emotions in the observer, such as amusement (in the case of embarrassment) and sympathy (in the case of shame) (Keltner, Young, & Buswell, 1997). Displays of love and desire coordinate the flirtatious interactions of potential romantic partners (Eibl-Eibesfeldt, 1989). Second, emotional communication conveys information about the sender’s mental states, intentions, and dispositions, which are critical to social interactions (Fridlund, 1992). The empirical literature suggests that emotional displays provide rapid, fairly reliable cues of the sender’s emotion, intentions, and disposition (for review, see Keltner & Kring, 1998). Contagious emotional responses provide a more direct route to the understanding of others’ mental states, leading individuals to experience similar responses to objects or events in the environment, coordinating individuals’ perception and action (Hatfield, Rapson, & Cacioppo, 1994). Finally, emotions serve as incentives for others’ social behavior: an individual’s Social Functions 7 expression and experience of emotion may reinforce another individual’s social behavior within ongoing interactions (e.g., Klinnert et al., 1983). For example, the display of positive emotion by both parents and children rewards desired behaviors and shifts in attention, thus increasing the frequency of those behaviors (e.g., Tronick, 1989). The literature on social referencing indicates that displays of more negative emotions deter others from engaging in undesirable behavior (Klinnert et al., 1983). To summarize, we have argued that group living presents humans with the problems of physical survival, reproduction, and group governance. Humans have evolved complex systems to meet these problems and opportunities, and emotions serve important functions within these systems by signaling that problems or opportunities exist and by coordinating the actions of interacting individuals. We now consider how culture elaborates upon primordial emotions. Culture and the social functions of elaborated emotions Evolutionary perspectives on emotion have always included a role for culture. Darwin begins The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872) with a description of a cross-cultural study in which he sent questionnaires to missionaries around the world, asking them to comment on the facial and bodily expressions of emotions shown by non-Western people. He concluded that some expressions are highly universal, whereas others are more variable, a conclusion that has withstood the test of time (Haidt & Keltner, 1999). Ekman has also always included an important role for culture in his “neuro-cultural” theory of emotions (1972). Ekman built on Tomkins’ (1963) notion of universal “affect programs”, suggesting that culture plays its role as a modulator of both inputs (what counts as an insult, or a loss?) and outputs (display rules about which emotions can be expressed in which circumstances). While Ekman’s critics have often ignored his writings about culture (e.g., Ekman, 1972), they have also pointed out ways in which culture may play a more profound role in human emotional life. Impressed by how culture and language give humans flexibility and creativity in designing their lives and societies, social constructivists concern themselves with the total package of meanings, social practices, norms, and institutions that are built up around emotions in human societies (Lutz, 1988; Lutz & Abu-Lughod, 1990; Shweder, 1993; White, 1990). We refer to these complex meanings as elaborated emotions. Elaborated emotions are shaped by social discourse and interaction, and by concepts of the self, morality, and social order (Markus & Kitayama, 1991; Shweder & Haidt, in press). Elaborated emotions vary across cultures, they cannot be experienced by infants, and they can last for years or centuries. For example, the hatred felt towards an historical enemy, although at any one moment in time comprised of brief emotional experiences, is made up of values, beliefs, images, action tendencies, and affective dispositions or sentiments that can pass from one generation to the next and last for extended periods of time1. In human beings, culture alters the use and expression of many evolved traits or systems, including primordial emotions, in several ways. Childhood instruction, culturally specific environmental conditions, and personal experiences determine culture specific elicitors of emotions, and shape the manner in which primordial emotions develop and are expressed. We will analyze cultural variation in emotion by applying our functionalist perspective to the sorts of objects that anthropologists and social constructivists are concerned with: meaning systems and emergent social phenomena such as institutions and practices. Social Functions 8 Modern approaches to culture often focus on how humans create the symbolic and material worlds that then shape, constrain, and enable them, as in Shweder’s (1989) succinct formulation, ”culture and psyche make each other up”. Cultures draw on many sources to create their symbolic worlds, including the human body and the phenomenological experiences it provides (Geertz, 1973; Lakoff, 1987). All cultures have noticed that people experience hunger, fatigue, illness, and sexual arousal, and all cultures have developed ethnotheories, customs, and practices that explain the origins and govern the interpretation of these experiences. Primordial emotions, we propose, provide universally available patterns of perception, experience, and action that cultures work into their ethnotheories, values, practices, and institutions. The primordial emotion of anger, for example, might be elaborated into a codified defense of the social-moral order, linked to satisfying feelings of righteousness, and valued as a prosocial force (e.g., the Ifaluk emotion of song, Lutz, 1988). Conversely, anger might be elaborated as a childish and destructive response whose expression is suppressed, leading to the use of other methods to solve interpersonal disputes (Briggs, 1970). Culture and the elaboration process loosen the link between a primordial emotion and the social problem it was designed to solve in two ways, as we elaborate below. First, cultures find new solutions to the ancient problems that emotions were designed to solve. Second, cultures find new uses for old emotions that have little to do with their “original” function. Once this loosening is recognized it becomes easier to reconcile evolutionary approaches (which focus on primordial emotions, and therefore find universality) and social constructionist approaches (which focus on elaborated emotions and therefore find cultural variation). New solutions to old problems: Artifacts and institutions Humans have developed an enormous variety of artifacts and technological solutions to the problems of survival, reproduction, and group governance. Cole (1995, p.32) writes that “the basic function of these artifacts is to coordinate human beings with the environment and each other." For example, the invention of weaponry, walls, and towns largely solves the problem of predator-avoidance and reduces the need for primordial fear reactions towards non-human animals, although such technological developments may then create new reasons to fear other people. Social institutions are a related means by which humans solve ancient problems. How do evolved artifacts, institutions, social structures, and technologies change the emotional profile of a culture? We perceive at least two possibilities. First, social institutions may work together with emotional systems, formalizing their functions and extending them into new domains. For example, the institution of marriage can build upon sexual and attachmentrelated emotions in cultures that practice love-based marriage, to create stable environments for child-rearing. Or marriage can build upon the emotions of the reciprocal altruism system in cultures that practice arranged marriages, to bind families together that trade daughters. Other social institutions formalize the functions of emotions. For example, Moore (1993) has observed how court related mediations between defendant and victim formalize exchanges of shame and forgiveness, and forge bonds following transgressions. Goffman (1967) likewise observed how group based status rituals that revolve around social practices, such as teasing and manners of dress and diction, ritualize displays of embarrassment and pride. In these circumstances, emotions may serve their original social functions in more pronounced, consistent, and consciously recognized ways. Second, innovations in technology, social structure, or social institutions may bypass Social Functions 9 certain emotional mechanisms, making those emotions less prevalent in a society. For example, cultures must address the problem that young women can become pregnant in their mid-teens, and that men who are not bound by marriage often do not help to raise their offspring. Many cultures therefore make girls marry right after their first menses. But another common solution is to delay female sexual activity by making a virtue of chastity, and by linking female sexuality outside of marriage to shame. This linkage was clearly in place in the United States until recently. The word “modesty” used to connote a feminine virtue in which properly socialized women felt shame when confronted by issues of sexuality, particularly their own. In this way American women experienced deferential, modesty related feelings such as embarrassment and shame that are comparable to the experience of lajya of Oriya women (Mennon & Shweder, 1994) and hasham of Awlad-Ali women (Abu-Lughod, 1986). But new technology (birth control), new social and economic facts (women working, and reducing the power differential with men), and new institutions (women’s groups and magazines) have greatly reduced the association of sexuality with shame. We cannot be certain, but it seems quite likely that the frequency of sexual shame/modesty experiences has greatly diminished for American women, as has the link between shame/modesty and appeasement or submissiveness functions in the context of sexuality. New problems for old solutions: Pre-adaptation and the creativity of culture In the course of evolution physical structures and behavioral patterns evolve under selection pressures for one purpose, but often are serviceable for a different purpose (Mayr, 1960; Rozin, 1976a). For example, the human tongue evolved as a mechanism to select and handle food, but it was pre-adapted to play a role in speech production, which has affected its current form. If the re-use of such a pre-adapted feature gives an advantage to certain individuals, the new use will become more common in succeeding generations, guided by a new set of selection pressures. This process can happen in biological evolution over the course of thousands of generations, or in cultural evolution over the course of a few years or decades. The process of cultural pre-adaptation is visible in the transition from primordial emotions to their elaborated forms. As a general principle, we suggest that primordial emotions will be recruited for new uses when features of their antecedents, appraisal patterns, or behavioral patterns match characteristics of the new domain where a solution to a similar social problem is needed. Certain emotion-related appraisals can be extended into new domains with slight changes. For example, because ideas can spread quickly from person to person, like germs, primordial disgust and its defense against microbial contagion is easily recruited and elaborated into a defense against ideological contagion, such as communist infiltration during the cold war. Once ideas are seen as “contaminating”, the solution to the problem is clear: infected individuals must be isolated, or expelled from the community. (See Lakoff, 1987, for more on the importance of metaphor in human thought.) Thus, the food rejection of primordial disgust (or core disgust, Rozin, Haidt & McCauley, 1993) is easily adaptable to social rejection, and most cultures seem to have some form of socio-moral disgust in response to certain classes of “offensive” social violations (Haidt et al., 1997). Pre-adaptation can occur at the level of emotion-related behavior as well, according to similar principles of similarity and generalization. Thus, many contexts requiring politeness, such as more formal interactions or those involving strangers, resemble those involving individuals in social hierarchies: the interactions are defined by potential threat. Theorists have Social Functions 10 argued that appeasement-related behaviors, including submissive displays and embarrassment, have been elaborated into more complex politeness and deference rituals (Eibl-Eibesfeldt, 1989; Visser, 1991). As one example, negotiating locations of limited space (e.g., doorways) often involve polite smiles, gaze aversion and specific gestures (head bows in other cultures) that draw upon the nonverbal cues of embarrassment. Emotion-related displays can be extended into new domains, thereby developing new uses. It will be important for future research to establish the extent to which the different components of primordial emotion are activated when one component of emotion (appraisals, display behavior) are generalized to a new domain. In sum, primordial emotions are universal, biologically based, coordinated response systems that have evolved to enable humans to meet the problems of physical survival, reproduction, and group governance. The creative process of culture, however, loosens the link between the primordial emotions and their functions, finding new solutions to old problems and new uses for old emotions. Evolutionary theorists are therefore right when they document high degrees of cross-cultural similarity in (primordial) emotion and emotion based preferences, interactions, and practices (e.g., Buss, 1992; Eibl-Eibesfeldt, 1989; Ekman, 1992). Social constructionists are also right when they document striking cultural variation in the uses and functions of (elaborated) emotions in human societies. We now apply this framework to a discussion of the biologically and culturally determined social functions of two specific emotions, disgust and embarrassment. Two case studies of primordial and elaborated emotion Disgust The dangers of parasites and bacteria are particularly acute for humans, who live in close quarters and eat a great variety of potentially dangerous foods. Humans are aided by a variety of food-related emotions, strategies and learning mechanisms, which work together as a functional system to achieve the right balance between exploration of new foods and the avoidance of dangerous foods (Rozin, 1996). Humans show neophobia, nibbling, and preparedness to associate nausea with new foods, even after a long delay (Seligman, 1971; Rozin, 1996). In humans, disgust is at the center of the food-selection system, having evolved from the more primitive reaction of distaste into a way of making people concerned about the contact history and nature of their potential foods, rather than just their sensory properties (Rozin, Haidt & McCauley, 1993). Disgust pushes against sensation seeking as part of the “omnivore’s dilemma”: the simultaneous interest in and fear of new foods (Rozin, 1976b). Human societies have developed diverse ways to safeguard their food supplies and to minimize the threats of bacteria and parasites. These solutions include technological innovations (cooking or curing meat, boiling or filtering water), institutions (government food inspectors), and cultural norms and food taboos whose violation triggers disgust or outrage. More recently, newspapers and television reports offer consumers advice from experts on what foods to eat, and how to prepare them. Perhaps because it has been partially freed from its original mission -- as a guardian of the mouth against dangerous foods -- disgust has been put to a variety of new uses. Its eliciting conditions have expanded so much that disgust may now be described as a social emotion whose function is to guard the social order against certain forms of deviance, and to guard the soul against certain forms of debasement (Rozin, Haidt and McCauley, in press). The link between Social Functions 11 material progress and the expansion of disgust in European history has been pointed out by Elias (1978). Disgust and its associated cognitions about contamination and purity are recruited into the maintenance of social groups with distinct boundaries, (e.g., the Indian caste system, upper class attitudes towards the lower class). Disgust is used in initiation rites (e.g., of American college fraternities) in which new members are forced to touch or eat the body products of others, thereby deliberately courting the risk of disease, yet simultaneously marking individuals as members of a communal sharing group. Embarrassment The establishment, maintenance, and preservation of status hierarchies is in part accomplished by dominance and submissive emotions (de Waal, 1996; Ohman, 1986). Embarrassment is a primary example. The primordial form of embarrassment involves submissive related behavior (Keltner, 1995) much akin to the appeasement displays of other species (e.g., gaze aversion, head movements down, controlled smiles) and submissive phenomenology (e.g., feelings of smallness and weakness) (Keltner & Buswell, 1996; Miller & Leary, 1992). Empirical evidence indicates that displays of embarrassment appease dominant individuals by evoking affiliative emotion and forgiveness (Keltner & Buswell, 1997). Several interactions that systematically recruit and revolve around embarrassment and other submissive emotions reinforce status hierarchies and status based relations. Status demarcating rituals, such as greeting and teasing, involve the ritualized display and elicitation of embarrassment (Goffman, 1967; Keltner, Young, Heerey, Oemig, & Monarch, 1998; de Waal, 1986, 1988), thus signaling the hierarchical relations between interacting individuals. Culture has evolved several new solutions to the problem of coordinating hierarchies. These include class and caste systems, aristocracy, status arrangements in groups and organizations, status signaling clothing (e.g., the length of a doctor’s lab coat in medical hospitals), linguistic practices (Brown & Levinson, 1987), status determinant, role-related norms for women and men, and moral codes dictating the individual’s place within a community (Shweder et al., in press). Status-related emotions have also been coopted in several more recent human social practices. Politeness systems, including table manners and conversational pragmatics, incorporate submissive emotion and gesture (Brown & Levinson, 1987; Keltner, Young, & Buswell, 1997). In many Hindu and Islamic cultures the expression of submissive emotions demonstrates feminine virtue (Abu-Lughod, 1986; Menon & Shweder, 1994). Flirtation and courtship involve submissive smiles of embarrassment (Eibl-Eibesfeldt, 1989) and dominant displays (Fisher, 1992). Conclusions and Future Prospects We have argued that emotions are part of systems that solve problems related to physical survival, reproduction, and group governance. Biologically based, universal primordial emotions involve experience, perception, physiology, and communication that solves these problems in the context of ongoing social interactions. Elaborated emotions are the total package of meanings, behaviors, social practices, and norms that are built up around primordial emotions in actual human societies. This approach integrates the insights of evolutionary and social constructionist approaches and points to the systematic role of emotion in social interactions, relationships, and cultural practices. We have intentionally focused on classes of emotions that solve specific social problems. Social Functions 12 Other emotions are likely to serve more context-general social functions: amusement may relate to the transformation of dangerous situations into safe ones (Keltner & Bonanno, 1997); interest may motivate general exploratory behavior and learning; happiness or contentment may signal to the individual her or his general level of social functioning (Nesse, 1990). These sorts of issues await further investigation. Our hope in this article is to prompt researchers to continue to examine the social functions of emotions, both in their universal and culturally elaborated forms. Towards this end, we make the following recommendations for future research. A first is to study emotion within theoretically relevant relationships. Many studies of emotion and social interaction have looked at strangers or, in more ambitious cases, friendships. We would suggest that the net needs to be cast more broadly, that researchers need to study emotion in different kinds of relationships. The study of embarrassment and shame may be most appropriate in interactions between superiors and subordinates. Love, desire, and jealousy are most fruitfully examined in interactions between actual or potential romantic partners. We further suggest, following our functional analysis, that empirical research may be most revealing when it focuses on the nature and consequences of emotions when relationship relevant problems (e.g., the maintenance of reciprocity between friends) are most salient, for example when stances towards them are being established, negotiated, or changed. The functions of love and desire are likely to be most clearly documented during initial stages of courtship or when a romantic bond is threatened. The manner in which shame and embarrassment help define status related roles is likely to be most illuminated when studying groups during dynamic times of status negotiation. Our second recommendation follows quite closely from the first: namely, study emotion in the context of social interactions and practices. A great deal of the study of emotion, even of the more social nature of emotion, examines the individual’s response to controlled stimuli. This sort of work is no doubt necessary; the understanding of emotion in social interaction rests upon the understanding of individual emotional response. Yet given the advances in the study of emotion, it may be time to study social interactions and practices that revolve around emotions. In the course of this review we have identified ways that cultural practices elaborate upon more primordial emotions (e.g., appeasement rituals), and ways in which primordial emotions are generalized to new practices (e.g., disgust related to unsavory ideologies). These different social practices have begun to be and should continue to be a focus of emotion research. The emphasis on emotions within social practice raises difficult conceptual issues. In studies of emotion related interactions, such as teasing, it will be necessary to treat the dyad or group as the unit of analysis (see comments below). Studies of how culture elaborates upon emotion will direct researchers to cultural objects and practices, such as etiquette manuals, religious texts, or institutions, that do not appear, from the traditional point of view, to involve emotion. Yet it is precisely in looking at these sorts of interactions and practices where one will find culturally elaborated emotion. Finally, a functional approach suggests that it is important to study systematic consequences. The functions of a specific emotion will in part be revealed by its regular consequences (e.g., Keltner & Gross, 1999). This view shifts the emphasis from looking at emotion as an outcome or dependent measure to the view that emotions themselves have important outcomes. As a field we know all too little about the systematic consequences of Social Functions 13 emotions, and this remains a very important line of inquiry. Relevant research can proceed at multiple levels of analysis. At the individual level of analysis, one would expect the disposition to experience and express specific emotions, for example anger or the lack of embarrassment, to be associated with specific social consequences. In moving to the dyad as the unit of analysis, one might look at how patterns of emotional expression and experience lead to specific consequences for ongoing interactions. Thus, we would expect timely displays of love and desire to predict more interest and intimacy in ongoing interactions between potential romantic partners. One could look at the long term consequences of patterns of emotional experience and expression for relationships. For example, following the analysis offered in this chapter, one might expect frequent displays of gratitude to predict the long term sense of fairness in friendships. Finally, it will be important for researchers to document the consequences of emotion for groups and cultures. Ritualized displays and experiences of embarrassment may contribute to the stability of group hierarchy. The culturally elaborated experience of disgust may correlate at the cultural level with specific stereotypes and outgroup prejudices. Emotion researchers have long moved across and around discipline specific theoretical inclinations and methodological practices. This tradition has led to great debate in the study of emotion (is emotion universal or culturally specific?), and great advances. The study of the social functions of emotion, we contend, depends vitally on the integration of ideas and evidence from different disciplines. Footnotes 1. An example may clarify the distinction: Is motherhood universal? We might speak of primordial motherhood as a system of tightly coordinated physical and psychological processes (involving gestation, parturition, and hormones that increase attachment) that is universal to humans and similar to motherhood in many nonhuman species. On the other hand, many researchers have documented cross-cultural variation in elaborated motherhood, e.g., single versus multiple mothering, breast versus bottle feeding, and valuation versus devaluation of the role of the mother (Kurtz, 1992). Social Functions 14 References Abu-Lughod, L. (1986). Veiled Sentiments. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. Ausubel, D.P. (1955). Relationships between shame and guilt in the socializing process. Psychological Review, 62, 378-390. Averill, J.R. (1980). A constructivist view of emotion. In R. Plutchik & H. Kellerman (Eds.), Emotion: Theory, research, and experience (pp. 305-339). New York: Academic Press. Axelrod, R. (1984). The evolution of cooperation. New York: Basic Books. Barrett, K.C., & Campos, J.J. (1987). Perspectives on emotional development II: A functionalist approach to emotions. In J.D. Osofsky (Ed.), Handbook of infant development (2nd ed.) (pp. 555-578). New York: Wiley-Interscience. Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment. New York: Basic Books. Briggs, J. L. (1970). Never in anger. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Brown, P., & Levinson, S.C. (1987). Politeness. New York: Cambridge University Press. Buss. D. (1992). Male preference mechanisms: Consequences for partner choice and intrasexual competition. In J.H. Barkow, L. Cosmides, & J. Tooby (Eds.). The adapted mind. (pp. 267-288). New York: Oxford University Press. Campos, J.J., Campos, R.G., & Barrett, K.C. (1989). Emergent themes in the study of emotional development and emotion regulation. Developmental Psychology, 25, 394-402. Clore, G. (1994). Why emotions are felt. In P. Ekman & R.J. Davidson (Eds.), The nature of emotion (pp.103-111). New York: Cambridge University. Cole, M. (1995). Culture and cognitive development: From cross-cultural research to creating systems of cultural mediation. Culture and Psychology, 1, 24-54. Darwin, C. (1872). The expression of emotions in man and animals. New York: Philosophical Library. Davidson, J.M. (1980). The psychobiology of sexual experience. In J. Davidson, & R. Davidson (Eds.), The psychobiology of consciousness. New York: Plenum Press. Davidson, R.J. (1993). Parsing affective space: Perspectives from neuropsychology and psychophysiology. Neuropsychology, 7, 464-475. Dunn, J. (1977). Distress and comfort. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Eibl-Eibesfeldt, I. (1989). Human Ethology. New York: Aldine de Gruyter Press. Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R.A., Miller, P.A., Fultz, J., Shell, R., Mathy, R.M. & Reno, R.R. (1989). Relation of sympathy and distress to prosocial behavior: A multimethod study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 55-66. Ekman, P. (1972). Universals and cultural differences in facial expressions of emotion. In J. Cole (Ed.). Nebraska Symposium of Motivation, 1971 (pp. 207-283). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. Ekman, P. (1984). Expression and the nature of emotion. In K. Scherer and P. Ekman (Eds.) Approaches to Emotion. (pp. 319-344). Hillsdale NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Ekman, P. (1992). An argument for basic emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 6, 169-200. Ekman, P., (1993). Facial expression and emotion. American Psychologist, 48, 384-392. Elias, N. (1978). The History of Manners. New York, NY: Pantheon Books. Social Functions 15 Ellis, B. (1992). The evolution of sexual attraction: Evaluative mechanisms in women. In J.H. Barkow, L. Cosmides, & J. Tooby (Eds.). The adapted mind. (pp. 267-288). New York: Oxford University Press. Fernald, A. (1992). Human maternal vocalizations to infants as biologically relevant signals: An evolutionary perspective. In J.H. Barkow, L. Cosmides, & J. Tooby (Eds.). The adapted mind. (pp. 391-428). New York: Oxford University Press. Fiske, A. P. (1991). Structures of social life. New York: Free Press. Fiske, A. P. (1990). Relativity within Moose culture: Four incommensurable models for social relationships. Ethos, 18, 180-204. Fisher, H. E. (1992). Anatomy of love. New York: Norton. Frank, R. H. (1988). Passions Within Reason. New York: Norton. Fridlund, A.J. (1992). The behavioral ecology and sociality of human faces. In M.S. Clark (Ed.) Emotion. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Frijda, N. (1986). The Emotions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Frijda, N. H., & Mesquita, B. (1994). The social roles and functions of emotions. In S. Kitayama & H. Marcus (Ed.), Emotion and culture: Empirical studies of mutual influenced. (pp. 5187). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures . New York: Basic Books. Gibbard, A. (1990). Wise choices, apt feelings. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. Goffman, E. (1967). Interaction Ritual: Essays on face-to-face behavior. Garden City, NY: Anchor. Gouldner, A.W. (1960). The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. American Sociological Review, 25, 161-178. Haidt, J., & Keltner, D. (In press). Culture and facial expression: Open ended methods find more faces and a gradient of universality Cognition and Emotion. Haidt, J., Koller, S., & Dias, M. (1993). Affect, culture, and morality, or is it wrong to eat your dog? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 613-628. Haidt, J., Rozin, P., McCauley, C. R., & Imada, S. (1997). Body, psyche, and culture: The relationship between disgust and morality. Psychology and Developing Societies, 9, 107131. Hatfield, E., Cacioppo, J.T., & Rapson, R.L. (1994). Emotional contagion. New York: Cambridge University Press. Hauser, M.D. (1996). The evolution of communication. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Izard, C.E. (1977). Human emotions. New York: Plenum Press. Johnson-Laird, P. N., & Oatley, K. (1992). Basic emotions, rationality, and folk theory. Cognition and Emotion, 6, 201-223. Keltner, D. (1995). The signs of appeasement: Evidence for the distinct displays of embarrassment, amusement, and shame. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 441454. Keltner, D. & Buswell, B. (1996). Evidence for the distinctness of embarrassment, shame, and guilt: A study of recalled antecedents and facial expressions of emotion. Cognition and Emotion, 10 (2), 155-172. Keltner, D., & Buswell, B.N. (1997). Embarrassment: Its distinct form and appeasement functions. Psychological Bulletin, 122, 250-270. Social Functions 16 Keltner, D., Ellsworth, P.C., & Edwards, K. (1993). Beyond simple pessimism: Effects of sadness and anger on social perception. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 740-752. Keltner, D., & Gross, J.J. (1999). Functional accounts of emotion. Cognition and Emotion, 13 (5) 467-480. Keltner, D., & Haidt, J. (1999). Social functions of emotions at multiple levels of analysis. Cognition and Emotion, 13 (5), 505-522. Keltner, D., & Kring, A. (1998). Emotion, social function, and psychopathology. Review of General Psychology, 2, 320-342. Keltner, D., Young, R., & Buswell, B.N. (1997). Appeasement in human emotion, personality, and social practice. Aggressive Behavior, 23, 359-374. Keltner, D., Young, R.C., Oemig, C., Heerey, E., & Monarch, N.D. (1998). Teasing in hierarchical and intimate relations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 12311247. Klinnert, M., Campos, J., Sorce, J., Emde, R., & Svejda, M. (1983). Emotions as behavior regulators: Social referencing in infants. In R. Plutchik & H. Kellerman (Eds.), Emotion theory, research, and experience: Vol. 2. Emotions in early development (pp. 57-68). New York: Academic Press. Krebs, J.R., & Davies, N.B. (1993). An introduction to behavioural ecology. Oxford, England: Blackwell press. Kurtz, S. (1992). All the mothers are one. New York: Columbia University Press. Lakoff, G. (1987). Women, fire, and dangerous things. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Lakoff, G. (1996). Moral politics: What conservatives know that liberals don't. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Emotion and adaptation. New York: Oxford University Press. LeDoux, J. (1996). The Emotional Brain. New York: Simon & Schuster. Lerner, J.S., & Keltner , D. (In press). Beyond valence: Toward a model of emotion specific influences on judgment and choice. Cognition and Emotion. Levenson, R.W. (1994). Human emotions: A functional view. In P. Ekman & R.J. Davidson (Eds.) The nature of emotion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Lutz, C.A. (1988). Unnatural emotions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Lutz, C.A., & Abu-Lughod, L. (1990). Introduction: Emotion, discourse, and the politics of everyday life. In C.A. Lutz & L. Abu-Lughod (Eds.). Language and the politics of emotion (pp. 1-23). New York: Cambridge University Press. Lutz, C.A. & White, G. (1986). The anthropology of emotion. Annual Review of Anthropology . Palo Alto, CA: Annual Reviews. Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98, 224-253. Mayr, E. (1960). The emergence of evolutionary novelties. In S. Tax (Ed.), Evolution after Darwin: Vol. 1. The evolution of life (pp. 349-380). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Menon, U., & Shweder, R. A. (1994). Kali's tongue: Cultural psychology, cultural consensus and the meaning of "shame" in Orissa, India. In H. Markus & S. Kitayama (Eds.), Culture and the Emotions (pp. 241-284). Washington DC: American Psychological Association. Social Functions 17 Miller, R.S. & Leary, M.R. (1992). Social sources and interactive functions of embarrassment. In M.Clark (Ed.) Emotion and Social Behavior. New York: Sage. Mineka, S., & Cook, M. (1988). Social learning and the acquisition of snake fear in monkeys. In T. R. Zentall & J. B. G. Galef (Eds.), Social learning: Psychological and biological perspectives (pp. 51-74). Hillsdale, N. J.: Lawrence Erlbaum. Moore, D.B. (1993). Shame, Forgiveness, & Juvenile Justice. Criminal Justice Ethics, 12, 3-25. Nesse, R. (1990). Evolutionary explanations of emotions. Human Nature, 1, 261-289. Oatley, K., & Johnson-Laird ** Ohman, A. (1986). Face the beast and fear the face: Animal and social fears as prototypes for evolutionary analysis of emotion. Psychophysiology, 23, 123-145. Ohman, A., & Dimberg, U. (1978). Facial expressions as conditioned stimuli for electrodermal responses: A case of “preparedness?”. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 36, 1251-1258. Plutchik, R. (1980). Emotion: A psychobioevolutionary synthesis. New York: Harper & Row. Porges, S.P. (1995). Orienting in a defensive world: Mammalian modifications of our evolutionary heritage. A polyvagal theory. Psychophysiology, 301-317. Rozin, P. (1976a). The evolution of intelligence and access to the cognitive unconscious. In J. A. Sprague & A. N. Epstein (Eds.), Progress in Psychobiology and Physiological Psychology, Vol. 6 (pp. 245-280). New York: Academic Press. Rozin, P. (1976b). The selection of food by rats, humans, and other animals, Advances in the study of behavior (pp. 21-76). New York: Academic Press. Rozin, P. (1996). Towards a psychology of food and eating: from motivation to module to model to marker, morality, meaning, and metaphor. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 5, 18-24. Rozin, P., & Fallon, A. (1987). A perspective on disgust. Psychological Review, 94, 2341. Rozin, P., Haidt, J., & McCauley, C. (1993). Disgust. In M. Lewis & J. Haviland (Eds.), Handbook of emotions ). New York: Guilford Press. Sapolsky, R. M. (1989). Hypercortisolism among socially subordinate wild baboons. Archives of General Psychiatry, 46, 1047-1051. Scherer, K.R. (1986). Vocal affect expression: A review and a model for future research. Psychological Bulletin, 99, 143-165. Schwarz, N. (1990). Feelings as information: Informational and motivational functions of affective states. In E.T. Higgins & R.M. Sorrentino (Eds.), Handbook of motivation and cognition, Volume 2 (pp. 527-561). New York: Guilford Press. Seligman, M. E. P. (1971). Phobias and preparedness. Behavior Therapy, 2, 307-320. Shin, M., Keltner, D., Shiota, L., & Haidt, J. (2000). The realm of positive emotion: Studies of lexicon and narrative. Manuscript in preparation. Shweder, R. (1989). Cultural psychology: What is it? In J. Stigler, R. Shweder, & G. Herdt (Eds.), Cultural psychology: The Chicago symposia on culture and human development New York: Cambridge University Press. Shweder, R.S. (1993). The cultural psychology of the emotions. In M. Lewis & J. M. Haviland, (Eds.), Handbook of Emotions (pp. 417-431). New York: Guilford Publications. Social Functions 18 Shweder, R.S., Much, N.C., Mahapatra, M., & Park, L. (In press). The “big three” of morality (autonomy, community, and divinity), and the “big three” explanations of suffering, as well. In A. Brandt & P. Rozin (Eds.). Morality and health. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Tangney, J.P. (1991). Moral affect: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 598-607. Tomkins, S.S. (1963). Affect, Imagery, & Consciousness. Volume II. The Negative Affects. New York: Springer-Verlag. Tomkins, S.S. (1984). Affect theory. In K. Scherer & P. Ekman (Eds) Approaches to emotion. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Tooby, J. & Cosmides, L. (1990). The past explains the present: Emotional adaptations and the structure of ancestral environments. Ethology and sociobiology, 11, 375-424. Trivers, R.L. (1971). The evolution of reciprocal altruism. Quarterly Review of Biology, 46, 35-57. Tronick, E. Z. (1989). Emotions and emotional communication in infants. American Psychologist, 44, 112-119. Visser, M. (1991). The Rituals of Dinner. New York: Grove Weidenfeld. de Waal, F.B.M. (1986). The integration of dominance and social bonding in primates. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 61, 459-479. de Waal, F.B.M. (1988). The reconciled hierarchy. In M.R.A. Chance (Ed.) Social Fabrics of the Mind (pp. 105-136). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. de Waal, F. B. M. (1996). Good Natured. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press Weber, M. (1957). The theory of social and economic organization. New York: The Free Press. White, G.M. (1990). Moral discourse and the rhetoric of emotions. In In C.A. Lutz & L. Abu-Lughod (Eds.). Language and the politics of emotion (pp. 46-68). New York: Cambridge University Press. Wilson, M.I., & Daly, M. (1996). Male sexual proprietariness and violence against wives. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 5, 2-6. Social Functions 19 Table 1. A taxonomy of problems and the functional systems and emotions that solve them. Social Functions 20 PROBLEM FUNCTIONAL SYSTEMS EMOTIONS SPECIFIC FUNCTIONS ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Problems of Physical Survival Predation Fight-Flight Fear Rage Avoidance of threat to self Removal of threat to self Disease Food-Selection Disgust Interest Avoid microbes/parasites Learn about new foods/resources Finding a mate Attachment Desire Romantic Love Sadness Increase likelihood of sexual contact Commit to long term bond Replace loss of mate Keeping mate Mate protection Jealousy Protect mate from rivals Protecting vulnerable children Caregiving Filial love Sympathy Increase bond between parent, offspring Reduce distress of vulnerable individuals Cooperation & Defection Reciprocal Altruism Guilt Moral Anger Gratitude Envy Repair own transgression of reciprocity Motivate other to repair transgression Signal, reward cooperative bond Reduce unfair differences in equality Group Organization Dominance-Submissive Problems of Reproduction Problems of Group Governance Shame & Pacify likely aggressor Embarrassment Contempt Reduce status of undeserving other Awe Endow entity greater than self with status _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________