Egypt: the Habit of Civilization

advertisement

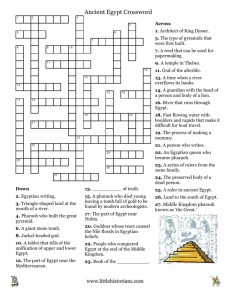

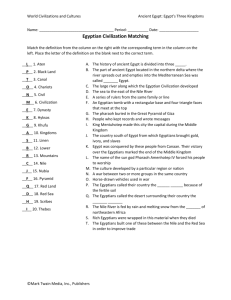

Chapter 7 Egypt: the Endurance of Civilization The Habit of Civilization Pages 113-115 Pattern of History Pages 115-118 Decline and Summary Pages 119-120 New Kingdom Pharaohs and Leadership Page 121 Works Consulted Page 123 Essential concept: How does environment shape a civilization? What are the benefits of continuity? What are the pitfalls of continuity? Ancient Egyptian Timeline 5000 BC First evidence of people settling along the Nile Delta 4400 - 4000 BC People practiced agriculture and domesticated sheep and goats, -- known for pottery 4000 - 3500 BC Amratian Society of Upper Egypt - first signs of hierarchical civilization 3200 BC Hieroglyphics developed 3110 - 2884 BC Menes joined Upper and Lower Egypt into one kingdom with the capitol at Memphis 3000 BC-2125 Old Kingdom Irrigation increased farmland, people worship the sun; age of pyramids (2125-1550) Middle Kingdom Period of chaos and change of capitals 1550-1069 New Kingdom: Era of Thutmose, Hatshepsut, Akhenaton, Tutankhamen and Ramses 712-657) Assyrians invasion. (525-404) The Persian Conquest The Persians invaded and ruled Egypt. They were pushed out in 404 B. C. 343 - 342 BC Artaxerxes I of Persia retakes Egypt 332 BC Alexander the Great invades Egypt 331 BC Alexandria is founded Egypt: The Habit of Civilization Gift of the Nile Geography In the valley of the Nile, the ancient Egyptians created one of the earliest, most magnificent and long-lasting of the world’s civilizations. “The Egyptian Nile “said the great Arab traveler Ibn Battuta, “surpasses all the rivers of the world in sweetness of taste, in length of course and utility. No other river can show such a continuous series of towns and villages along its banks, nor a basin so intensively cultivated.” The civilization of Egypt, like those of Mesopotamia, India, and China, drew its life from a river. Like the Ganges in India, the Nile was worshipped as a divine force itself, as the giver of life. Egypt has been called, the Gift of the Nile. This then was a river like no other; running for six hundred miles between dunes and cliffs, the narrow ribbon of blue water and green fields on average only six mile wide. Egypt’s geography shaped the very character if its civilization and its people. Where the spirit of Iraq was pessimistic, here when the Nile flooded each year, as the ancients said, “the fields laugh, men’s faces light up and God rejoices in his heart.” From the life-renewing soil left by the inundation, the Egyptians drew a cheerful confidence in humanity, in the permanence and stability of things. In striking contrast to Mesopotamia, theirs was always an optimistic civilization. Strong natural frontiers; a rich agricultural soil produced by the natural flooding; tremendous mineral resources in stone and precious metals generated a magical selfconfidence and a unique cultural purity of over three thousand years of Egyptian history. Farming villages appear in the flood plain in the sixth millennium BC, cultivating wheat and barley and domesticating sheep and goats. During the next two millennia, there was a gradual formation of several tiny kingdoms along the valley, and in the Delta, the two regions which still present the fundamental divide in Egyptian history, culture and geography. After 4000BC, there was a substantial increase in population and size of the settlements; developed crafts and technological skills are in evidence, working in stone, bronze, copper, and slate. The first small towns, walled in mudbrick, appear by 3500BC, with the rich tombs of local dynasties. Pre-Dynastic Egypt Beginning just before the Predynastic period, Egyptian culture was already beginning to resemble greatly the Pharaonic ages that would soon come after, and rapidly at that. In a transition period of a thousand years (about which little is still known), nearly all the archetypal characteristics appeared, and beginning in 5500 BC we find evidence of organized, permanent settlements focused around agriculture. Hunting was no longer a major support for existence now that the Egyptian diet was made up of domesticated cattle, sheep, pigs and goats, as well as cereal grains such as wheat and barley. Artifacts of stone were supplemented by those of metal, and the crafts of basketry, pottery, weaving, and the tanning of animal hides became part of the daily life. The transition from primitive nomadic tribes to traditional civilization was nearly complete. 113 The Chalcolithic period, also called the "Primitive" Predynastic, marks the beginning of the true Pre-dynastic cultures both in the north and in the south. The southern cultures, particularly that of the Badarian, were almost completely agrarian (farmers), but their northern counterparts, such as the Faiyum who were oasis dwellers, still relied on hunting and fishing for the majority of their diet. Predictably, the various craftworks developed along further lines at a rapid pace. Stoneworking, particularly that involved in the making of blades and points, reached a level almost that of the Old Kingdom industries that would follow. Furniture too, was a major object of creation; again, many artifacts already resembling what would come. Objects began to be made not only with a function, but also with an aesthetic value. Pottery was painted and decorated, particularly the black-topped clay pots and vases that this era is noted for; bone and ivory combs, figurines, and tableware, are found in great numbers, as is jewelry of all types and materials. It would seem that while the rest of the world at large was still in the darkness of primitivism, the Pre=dynastic Egyptians were already creating a world of beauty. Uniting Egypt No time of the Pre-dynastic offers as many questions as the period of unification of southern and northern Egypt. Exactly who conquered whom is the first. Many sources point to the event as the victory of the south over the north, yet the resulting social system resembles more that of the north than the south. Exactly who the first king of unified Egypt is also difficult to say, or even when the actual unification occurred. The most powerful piece of data on this event is the Narmer Palette, a triangular piece of black basalt depicting a king whose name is given as Nar-Mer in the hieroglyphs. On the obverse, he is shown wearing the white crown of the south and holding a mace about to crush the head of a northern foe, and on the reverse, the same figure is shown wearing the red crown of the north while a bull (a symbol of the pharaoh's power) rages below him, smashing the walls of a city and trampling yet another foe. Another artifact, the "Scorpion" Macehead, depicts a similar figure, only this time the name is given by the pictogram of a scorpion. This king-figure is called in many documents alternatively Narmer, or Aha, and if the historian Eratosthenes is to be believed, this is the legendary King Meni, or Menes. Whether "King Scorpion" is the same person as Narmer is a bit of contention, but the two are widely accepted to be the same. If these two artifacts, and others like them from the same period, do in fact depict this as the first king of unified Egypt, then the date for the Unification can be placed sometime between 3150 and 3110 BC. Kingship and Divinity 114 Out of prehistoric tribal struggles, the “great tradition” emerged: the first true state in the world. The ideological basis of prehistoric kingship, its symbols and myths, proved uniquely longlasting, indeed it lay at the heart of Egyptian civilization. The temple was a symbolic representation of the original mound of creation, with the simple reed shrine surrounding the perch on which the hawk had landed. A whole theory of society was bound up with this myth. For the temple was not only a depiction of the first place, but of the first time, the time when the pattern of a stable society was handed down to humankind; a pattern to be maintained by kingship, law, religion, and ritual, and which it was believed, would suffice for eternity as long as the rituals were correctly performed. The universe and civil society were conceived of as static. Progress, change, new questions, new answers were simply not needed. And they would not be needed for three millennia Mainstays And Themes The Pyramid Age So in the pre-dynastic period, the mainstays of later Egypt: efficient farming, metalworking, centrally organized irrigation, pottery, stone-working, ceremonial and monumental architecture, elaborate burials, and long-distance trade were all established. For the Egyptians then, divine kingship was the guarantee of a stable cosmos. And so the key themes of Egyptian history were laid down very early; centralized power, royal rituals, and the cult of the dead intertwined to form the ideology of the world’s first state. Where the narrow Nile valley meets the green expanse of the Delta, close by today’s capital of Cairo, Menes built his royal city Memphis. Slightly to the south of Memphis, at Saqqara the mudbrick architecture of Abydos was turned into stone: the world’s first large-scale stone architecture. The necropolis of Saqqara extends for miles. Overshadowing the whole area was a new innovation, a gigantic stepped tomb, 200 feet high: the first of the pyramids. This idea of Zoser and his architect Imhotep ( who was later deified for his accomplishments) caught on in an extraordinary fashion. In a handful of generations around 2500Bc, a series of gifted Kings Senefru, Khufu, Khafre built bigger and bigger as each seemed to try to outdo his predecessor, created the greatest series of funeral monuments the world has ever seen. Djedefre, son of Khufu, is currently credited with the construction of the sphinx. Primary Source There are many myths surrounding the building of the pyramids. In the Hollywood biblical epic version, slave gangs were whipped along by tyrannical masters. But though slavery existed in ancient Egypt, this was not a slave society. When the Greek historian Herodotus visited Egypt in the fifth century B.C., he was told by his guides that 100,000 workers had labored for 20 years to build Khufu's pyramid. Even 20,000 workers, a number closer to recent estimates, is comparable to the populations of large cities in the Near East during the third millennium B.C. From hieroglyphic inscriptions and graffiti we infer that skilled builders and craftsmen probably worked year round at the pyramid construction site. Peasant farmers from the surrounding villages and provinces rotated in and out of a labor force organized into competing gangs with names such as "friends of Khufu" and" Drunkards of Menkaure". The pyramid projects must have been a tremendous socializing force in the early Egyptian kingdom-young conscripts from hamlets and villages far and wide departing for Giza where they entered their respective gangs. 115 Legitmation of authority Old Kingdom An enormous support system must have existed at Giza for at least 67 years, the combined minimum lengths of Khufu, Khafre and Menkaure's reigns. such support would have included production facilities for food, ceramics and building materials (gypsum mortar, stone, wood and metal tools); storage facilities for food, fuel and other supplies, housing for workmen, their families and priests responsible for services in pyramid Nine temples that remained in use long after the main building phase was completed, and a cemetery for workers who died in the employ of the royal necropolis. The pyramid builders were not slaves but peasants conscripted on a rotating part-time basis, working under the supervision of skilled artisans and craftsmen who not only built the pyramid complexes for the kings and nobility, but also designed and constructed their own, more modest tombs. Dr. Zahi Hawass , Former Minister of Antiquities, Egypt The Egyptian word for pyramid means ‘a place of ascension’. All civilizations have sought validation for their power over the masses by creating great public symbols. And what more awe-inspiring demonstration could there by of the real power of kings who could command such memorials? Scholars now believe that in the Egyptian pyramid the dead King becomes a manifestation of the Sun God himself. In the step pyramid at Saqqara one can see the transitional stage in the idea: a stair case on which the king’s spirit could ascend to heaven and then go back to his tomb. The true pyramid is simply an extension of this idea. It is both an image of the rays of the Sun God coming down to ear and a celestial ramp for the ascension of the soul: a typical piece of Egyptian imagination, in which an immaterial concept is represented in a material form. On winter days in Giza, it is often possible to see the sun breaking through the clouds and shining down at the same angle as the pyramids: a stairway to heaven, formed by the rays on which the king, ‘nimble and wise, could ascend to the indestructible stars.’ Pattern of History For much of its ancient history Egypt remained extraordinarily stable for long periods as typified in the unchanging style of its art. The Old Kingdom (c2700-2100 BC) whose zenith was the Pyramid age, saw a big increase in population. This placed great reliance on maximizing the use of the land flooded and fertilized each year by the inundations. Around 2200-2100 BC, the same prolonged dry period which caused such problems for the Ur III kings in Mesopotamia, brought a series of consistently low floods and precipitated half a century of famine. However, during Pepi II's reign, we find increasing evidence of the power and wealth of high officials in Egypt, with decentralization of control away from the capital, Memphis. 116 These nobles built huge, elaborate tombs at Akhmin, Abydos, Edfu and Elephantine, and it is clear that their wealth enhanced their status to the detriment of the king's. Because the positions of these officials was now hereditary, they now owned considerable land which was passed from father to son. Therefore, their allegiance and loyalty to the throne became very casual as their wealth gave them independence from the king. Administration of the country became difficult and so it was Pepi II who divided the position of vizier so that now there was a vizier of Upper Egypt and another of Lower Egypt. Yet the power of these local rulers continued to flourish as the king grew ever older, and probably less of an able ruler. Middle Kingdom During the interregnum after the Old Kingdom, a small independent kingdom had grown up around the town of Thebes in Upper Egypt. The Theban Mentuhotep II restored the unity of the two lands in 2130 BC, and the Theban tradition tended to view him as a second founder of a united Egypt comparable to Menes. Thebes itself became the southern ‘capital’ which it remains today. Through both the Middle Kingdom (1991-1786 BC) and the New Kingdom (1587-1085 BC), the once small country town of Thebes was adorned with a series of gigantic shrines and a series of huge mortuary temples. There is no evidence in this long period that people seriously considered alternative forms of government to that of rule by a diving king: indeed evidence for revolts against the Pharaonic state is virtually non-existent. In modern terms, theirs was a provider state, providing a basic standard of living to its entire people through control of the resources of the Nile In return, enormous surpluses could be spent by the rulers on tombs, temples, and palaces. Through these great buildings the state expressed its ideologies of power: its belief in the indivisibility of divine and earthly rule, and in the need of a stable cosmos. Such ideas may have been essential requirements for the creation of civilization initially. Economics Without a system of money at the local level, Egypt needed an elaborate system of redistribution of surpluses to sustain the huge elite and the entire service sector. It was patriarchal and to a degree authoritarian; but it is not far from many modern Near Eastern countries today. But the arbitrariness had to be matched by responsibility. God, as king, had consented to guide the nation. Societies had a pledge that the unpredictable forces of nature would be well disposed and bring prosperity and peace, which generally they did, for three thousand years. Nor did the Egyptian view lack ethical content, for truth and justice, known as Ma’at, were ‘what the gods live by’ and were an essential element in the established order. As the great Egyptologist Henri Frankfort said, “Pharaoh was not in our sense a tyrant, nor was his service slavery”. 117 Ma’at Egyptians believed that the universe was above everything else an ordered and rational place. It functioned with predictability and regularity; the cycles of the universe always remained constant; in the moral sphere, purity was rewarded and sin was punished. Both morally and physically, the universe was in perfect balance. The Egyptian word for this balance was the word for "truth," ma'at; this is perhaps the single most important aspect of Egyptian culture. Ma’at was the philosophy of justice, law, and ethics, concepts that the ancient Egyptians believed to be the foundation of universal order, truth, and harmony. Personified as a goddess, Ma’at is depicted as a woman wearing an ostrich feather on her head, a symbol of the principles she represents. Controlling the movement of the stars and the seasonal flooding of the Nile River, Ma’at also dictated codes of tradition and customs. Ma’at was central to funerary practices in which the heart of the deceased, considered the center of intellect and memory, was weighed against a feather and judged worthy of eternal life Role of Pharaoh The pharaoh was the living representation of Ma’at in which Egypt held the position of highest regard in the world. The pharaoh was not simply a priest-king. He was the upholder of the universal order. As long as the pharaoh and the people honored the gods and obeyed the law set down for them, Ma’at would be in balance and all would be well. But should the pharaoh fail, not only the people but the whole world would suffer, for Ma’at formed the basis of all things. Thus, the pharaoh was the center of order and controlled every facet of Egyptian life. Deviation from the tenets of ma’at could prove disastrous for the pharaoh whose responsibility it was to maintain order throughout the kingdom. In line with the utopian order of Ma’at, the pharaoh was always depicted as a perfectly handsome, athletic male – regardless of his appearance in real life. It was also important that the pharaoh was seen as a powerful and invincible leader and so he was often depicted smiting the enemy. Even those who did not set foot on the battlefield were keen to exploit this symbolism. The mediator between humans and gods was the king. The crowning of a new king transformed him into a living god; What is the king of Upper Egypt? What is the king of Lower Egypt? It is a god by whose guidance you live the Father and the Mother of all humans, Alone by himself The one who is unique (Rekhmire) The most important task for the king was to serve the gods and by that making it possible to maintain order and structure in society. He is seen as the son of several gods, not just one; Ramesses III as the son of Amon, Atum, Ptah, Shu, Thoth, Osiris, Horus and others. 118 He becomes in fact their incarnation on earth. By observing and obeying the will of the gods he upholds Ma´at, the principle of order, justice and harmony, which is necessary for existence to continue. Here the daily Temple Cult plays an important part. As the living king was a Horus, when he died, his successor became the new living image of Horus and the dead king became Osiris, Horus' father. The cyclic renewal of the creation was thus ensured by the constantly renewing monarchy. As the heir of Osiris, Horus also represents all that is just and right. Myth and Authority Second Intermediate period After Osiris was murdered by his brother Seth, his heritage was claimed by Seth, who tried to cast aside Osiris' legal heir. With the help of his mother Isis, Horus demands justice and attacks his uncle. When Horus emerges victoriously from his battles with Seth, Osiris' heritage is given to him, ending the chaos and uncertainty of Seth's rule. Because of his battles against injustice, Horus is also seen as a protector-god, a god who attacks and destroys evil where- and whenever he can. As the god of the heavens, he is often represented as a falcon or as a man with the head of a falcon. As such, he is the protector of the heaven and of the sun god Re. The Egyptian, then believed that he or she understood how the universe operated; all phenomena could be explained by an appeal to this understanding of the rationality of the universe. The Middle Kingdom fell because of the weakness of its later kings, which lead to Egypt being invaded by an Asiatic, desert people called the Hyksos. These invaders made themselves kings and held the country for more than two centuries. The word Hyksos goes back to an Egyptian phrase meaning "ruler of foreign lands". The Hyksos, sometimes referred to as the Shepherd Kings or Desert Princes, sacked the old capital of Memphis and built their capital at Avaris, in the Delta. The dynasty consisted of five possibly six kings, the best-known being Apepi I, who reigned for up to 40 years. Looking back over what the contemporary sources have revealed concerning the humiliating Hyksos occupation we find truth and falsity in almost equal measure. R. Weill was the first to insist on the distortion due to a type of literary fiction which became an established convention of Egyptian historical writing. A period of desolation and anarchy is painted in exaggeratedly lurid colors, usually for the glorification of a 119 monarch to whom the salvation of the country is ascribed. It is not to be believed that a mighty host of Asiatic invaders descended upon the Delta like a whirlwind and, occupying Memphis, inflicted upon the natives every kind of cruelty. The rare remains of the Hyksos kings point rather to an earnest endeavor to conciliate the inhabitants and to ape the attributes and the trappings of the weak Pharaohs whom they disodged. The Hyksos episode was not without effecting certain changes in the material civilization of Egypt. Their rule brought many technical innovations to Egypt, from bronze working, pottery and looms to new musical instruments and musical styles. New breeds of animals and crops were introduced. But the most important changes was in the area of warfare; composite bows, new types of daggers and scimitars, and above all the horse and chariot. In many ways the Hyksos modernized Egypt, and ultimately, Egypt was to benefit from their rule. New Kingdom The 18th Dynasty began a period of unprecedented success in international affairs for Egypt. There was a succession of extraordinary and able kings and queens who laid the foundations of a strong Egypt and bequeathed a prosperous economy to the kings of the 19th dynasty. There was Ahmose who expelled the Hyksos, followed by Thutmose I's conquest in the Near East and Africa. Queen Hatshepsut and Thutmose III who made Egypt into an ancient super power. The magnificent Amenhotep III, who began an artistic revolution. Akhenaton and Nefertiti who began a religious revolution - the concept of one god. Finally there was Tutankhamen who is so famous in our modern age. In the 19th dynasty, Seti I's reign looked for its model to the mid-18th dynasty and was a time of considerable prosperity. He restored countless monuments. His temple at Abydos exhibits some of the finest carved wall reliefs. His son Rameses II is the major figure of the dynasty. Around this time the Hittites had become a dominant Asiatic power. An uneasy balance of power developed between the two kingdoms, which was punctuated by wars and treaties. Although brave in battle, Rameses was an inept military strategist and spent the rest of his life bolstering his image with huge building projects. His name is found everywhere on monuments and buildings in Egypt, and he frequently usurped the works of his predecessors and inscribed his own name on statues which do not represent him. The smallest repair of a sanctuary was sufficient excuse for him to have his name inscribed on every prominent part of the building. His greatest works were the rock-hewn temple of Abu Simbel, dedicated to Amun, Ra-Harmachis, and Ptah; its length is 185 feet, its height 90 feet, and the four colossal statues of the king in front of it - cut from the living rock - are 60 feet high. He also added to the temple of Amenhotep III at Luxor and completed the hall of columns at Karnak - still the largest columned room of any building in the world. After Rameses’ death Egypt fell into decline. Luckily for Egypt, her prestige and preeminence as a world superpower was such that this process took a long time. Only one other king, Rameses III (1184 - 1153 BC), was able to temporarily halt this process. 120 Fall and Summary In the first millennium BC, there were no fundamental changes: the overall impression was of continuity of ancient practice with no question of a radical restructuring of Egypt’s institutions. Their state was now stuck in the past, surrounded by powerful neighbors who were no longer theocratic states. Perhaps the greatest change though was the idea that the king was no longer divine; no longer the repository of righteousness, truth and justice, or the ally of the gods. The first millennium BC was a time of great brutality and upheaval across the Near East, and it may be that the ideological basis of Egyptian civilization was already undermined before it fell to the Greeks in the 4th century BC. In the late 14th century, those questions of continuity were examined by the great Islamic historian Ibn Khaldun. His concerns were the nature of civilization, its rise and decline. He considered that settled co-operative human life was the goal of civilization; that it went in cycles of growth and decay like all forms of life. He thought that over-consumption in society was an inevitable cause of decline. But he believed that under certain favorable conditions of geography and climate, of the character and customs of the people, of their sense of group identity, culture could acquire a rootedness that he called the ‘habit of civilization’. And in all history, Egypt was perhaps the best example of that habit. The pharaohs had political power for three thousand years. ‘So the habit of civilization was continuous here, nowhere else in the world was it more firmly rooted.’ And such an idea helps explain Egypt’s continuing cultural leadership in the Arab world. At the beginning lay the early Egyptian state, the first comprehensive attempt in human history to satisfy the needs of men and women to live together an ordered state with a degree of happiness and material well- being. And so far it has been one of the most successful. 121 New Kingdom Pharaohs Quotes "The task of the leader is to get his people from where they are to where they have not been." — Henry Kissinger "The leader is one who mobilizes others toward a goal shared by leaders and followers. ... Leaders, followers and goals make up the three equally necessary supports for leadership." — Gary Wills "The leader has to be practical and a realist, yet must talk the language of the visionary and the idealist." — Eric Hoffer The very essence of leadership is its purpose. And the purpose of leadership is to accomplish a task. That is what leadership does–and what it does is more important than what it is or how it works. ~Colonel Dandridge M. Malone Don't tell people how to do things, tell them what to do and let them surprise you with their results. George S. Patton Essay. Read through the quotes above. Pick a quote that you feel reflects genuine leadership and also pertains to the pharaohs of Ancient Egypt. Use the criteria in the quote to measure the leadership of three (3) of the pharaohs. Pick two that live up to the standard and one that does not. Make sure to show with specific facts from your notes how each pharaoh lives up to or falls short of your selected quote. You may use a pharaoh who is not on the list for one of your choices. Pepys II Hatshepsut Thutmose III Akenhenaten Ramses the Great (II) Write the quote at the beginning of your paper as a kind of thesis on the idea of leadership. Your essay should be three (3) paragraphs long. It should start with the quote and end with a concluding sentence about the idea of leadership. 122 Works Consulted "Eighteenth Dynasty." Egypt: History. Tour Egypt, 20 June 2011. Web. 14 Feb. 2013. <http://www.touregypt.net/hdyn18a.htm>. Hawass, Zahi, Dr. "The Pyramid Builders." The Plateau: The Website of Dr. Zahi Hawass. 19952008. Guardian's Egypt. 4 June 2008<http://www.guardians.net/egypt/>. Path: The Plateau; Sphinx and Pyramids; The Pyramid Builders. Hooker, Richard. World Civilizations. 9 July 1999. Washington State University. May 2008 http://www.wsu.edu:8080/%7Edee/WORLD.HTM. Kinnear, Jacques. “Horus.” Gods and Religion in Ancient Egypt. 23 January 2007. The Ancient Egypt Site. 16 June 2009http://www.ancient-egypt.org/index.html. Millmore, Mark. "Kings and Queens." Discovering Ancient Egypt. Mark Millmore, 2013. Web. 14 Feb. 2013. <http://www.eyelid.co.uk/index.htm>. "Predynastic (5,500 - 3,100 BC)." Egypt: History - Predynastic Period. Tour Egypt, 20 June 2011. Web. 13 Feb. 2013. <http://www.touregypt.net/ebph5.htm>. "Second Intermediate Period." Egypt: History. Tour Egypt, 20 June 2011. Web. 14 Feb. 2013. <http://www.touregypt.net/hsecin1a.htm>. Wood, Michael. Legacy: The Search for Ancient Civilizations. New York: Sterling Publishing,1992. Out of Print. 123