Lesson Plans: The Industrial Revolution in Britain

advertisement

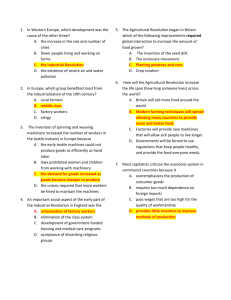

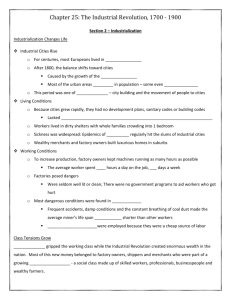

LESSON PLANS THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION IN BRITAIN Kenneth A. Poppe Hall High School West Hartford Public Schools West Hartford, Connecticut 06117 NEH Summer Seminar 2000 Historical Interpretations of the Industrial Revolution in Britain University of Massachusetts Dartmouth at the University of Nottingham Lesson Plans: #1 #2 #3 #4 #5 Analyzing a Textbook Child Labor Southey v. Macaulay Cities and factories Idleness as a Vice 2 LESSON PLAN FORMAT: The Industrial Revolution in Britain Lesson topic: # 1 Analyzing a textbook Main Unit Objective: (from the National Standards for History) The students understand the early industrialization and the importance of developments in England. Specific Lesson Objective(s): (from the National Standards for History) The students (1) will be able to compare different historical narratives of the Industrial Revolution and analyze the different portrayals and perspectives they present and (2) will be able to interrogate historical data to detect and evaluate bias, distortion, and propaganda by omission, suppression or invention of facts. Lesson Design: (This exercise might be utilized at the beginning or at the end of a unit on the Industrialization.) Initiation: In preparation for this lesson, students were given the 'textbook critique' sheet of questions. To begin this class, the teacher might focus on one or two of the key questions on the study sheet to determine whether the students were able to analyze the text. (5-10 minutes) Main Lesson Activities: Students can then be organized into groups of 2 or 3 for the purpose of sharing answers to their worksheets. (10 minutes) Then the teacher can distribute copies of other textbooks to each group. The task for students would be to briefly review those texts for answers to specific questions. For example, what pictures are included? What resources are mentioned in the bibliography? What is the overall message of the text? (15-20 minutes) Closure: Each group should select a spokesperson to share its group findings. Are the textbooks different? Why do you think that is? Which seems the most accurate? (5-8 minutes) Resources: (1) copies of the 'textbook critique' and (2) copies of additional textbooks for the purpose of reviewing. 3 Resource sheet for Lesson # 1: Textbook Critique Sheet on the Industrial Revolution (1) List the title, author, publisher and date of publication. How many pages are devoted to the subject? (2) Does the text have a specific bibliography for the section on the Industrial Revolution? If so, list several of the authors/historians. (3) What pictures are included? What do they show? List title and artist. (4) What inventors/inventions are mentioned? Does the text go into detail about how the inventions or machines actually worked? (5) What specific industries are emphasized in the text? (coal, silk, cotton, wool, lace, etc) (6) How does the author explain the causes of the Industrial Revolution in Britain? Is there a list of causes? Is there a clear statement of what the author believes is the main cause? (7) Does the section only mention Britain or does it deal with other European nations? (8) Are specific cities mentioned in the text? (9) Does the text paint a 'pessimistic and dark side' or an 'optimistic and cheerful side' of the Industrial Revolution? Does the text state that workers' earnings, standard of living and housing conditions improved, stayed the same or declined? (10) Does the text mention poetry, art or fiction dealing with the Industrial Revolution? (11) How does the text describe the factory owners? Favorably or unfavorably? Are any mentioned by name? 4 (12) What does the text say about the impact of the Revolution on the family, the role of women and the development of cities? (13) Does the text say anything about the role of Nonconformist or Dissenter religious groups? (14) Does the text include excerpts from primary sources? If so, which ones? (15) Does the text include the topic of reform and Parliamentary legislation, such as the Chartists, the Luddites, the 1833 Factory Act, the Ten Hours Act, and the New Poor law? 5 LESSON PLAN FORMAT: The Industrial Revolution in Britain Lesson Topic: # 2 Child Labor in England Main Unit Objective: (from the National Standards for History) The students understand the early industrialization and the importance of developments in England. Specific Lesson Objective: (from the National Standards for History) The students will be able to (1) explain how industrialization affected the daily lives of children and (2) compare primary sources about a problem and analyze the different perspectives they present. Lesson Design: Initiation: In preparation for this lesson, students were given excerpts from EIGHT documents on child labor, three describing positive conditions and three describing negative conditions. They were to complete a worksheet on which they could compare the documents. At the beginning of class, the students would be organized into groups of 2 or 3 for the purpose of sharing their homework charts. (10 minutes) Main Lesson Activities: The teacher would then distribute two additional documents for the students in groups to discuss and add to their chart. (10 minutes) The teacher would lead a large group discussion about the differences that the documents show about child labor and about possible reasons for those differences OR allow the students to role play the authors of those documents and simulate a Parliamentary debate. (15 minutes) Closure: The teacher would briefly introduce the main provisions of the Factory Act (1832), the Coal Mine Act (1842) and the Ten Hours Act (1847) and ask students to explain the connection between those provisions and the documents. Resources: (1) homework chart and (2) copies of primary sources 6 Lesson Plan # 2 Homework Chart AUTHOR OF THE DOCUMENT A B C D E F G H DATE DESCRIPTION OF CHILD LABOR 7 I J Lesson Plan # 2 Primary Sources on Child Labor Document A Michael Sadler, member of Parliament, "A Factory Girl's Last Day", 1832 'Twas on a winter's morning, The weather wet and wild, Three hours before the dawning The father roused his child; Her daily morsel bringing, The darksome room he paced, And cried, 'The bell is ringing, My hapless darling, haste!' 'Father, I'm up, but weary, I scarce can reach the door, And long the way and dreary,-O carry me once more! To help us we've no mother; And you have no employ; They killed my little brother,-Like him I'll work and die!' Her wasted form seemed nothing,-The load was at his heart; The sufferer he kept soothing Till at the mill they part. The overlooker met her, As to her frame she crept, And with his thong he beat her, And cursed her as she wept. 8 Alas! What hours of horror Made up her last day; In toil, and pain, and sorrow, They slowly passed away: It seemed, as she grew weaker, The threads they oftener broke, The rapid wheels ran quicker, And heavier fell the stroke. The sun had long descended, But night brought no repose; Her day began and ended As cruel tyrants chose. At length a little neighbor Her halfpenny she paid, To take her last hour's labour, While by her frame she laid. At last, the engine ceasing, The captives homeward rushed; She thought her strength increasing-'Twas hope her spirits flushed: She left, but oft she tarried; She fell and rose no more, Till, by her comrades carried, She reached her father's door. All night, with tortured feeling, He watched his speechless child; While, close behind her kneeling, She knew him not, nor smiled. Again the factory's ringing Her last perceptions tried; When, from her straw-bed springing, 'Tis time!' she shrieked, and died! That night a chariot passed her, While on the ground she lay; The daughters of her master An evening visit pay; 9 Their tender hearts were sighing, As negro wrongs were told, While the white slave lay dying Who gained their father's gold! Document B James Pattison, silk manufacturer, 1816, testimony in Parliament Q--What is the state of health of the children in your manufactory? A--I may say, from my own experience of nearly forty years, unexceptionally good. Q--Could any system of inspection of the mills be established without inconvenience? A--The visits are inconvenient as the attention of the children was always drawn from their duty by the appearance of any new faces.… Q--Why do you take the children so young? A--Partly to oblige their parents and because at that early age their fingers are more supple, and they are more easily led into the habit of performing the duties of their situation. Q--Are we to understand that children of six or seven are employed ten hours and a half? A--yesQ--Have you ever observed any inconvenience to the health of these very young children? A--I can only state that they enjoy very excellent health. Q--Do you conceive that working in the factories is favourable to the morals of young people? A--It keeps them out of mischief. They are less likely to contract evil habits than if they are idling their time away. Document C C. T. Thackrah, "The Effects of Arts, Trades and Professions, and of Civic States Habits of Living, on Health and Longevity.", 1844 No man of humanity can reflect without distress on the state of thousands of children roused from their beds at any early hour, hurried to the mills, and kept there till a late hour of night…kept in an atmosphere impure loaded with noxious dust. Recreation is out of the question. There is scarcely time for meals…I stood in Oxford-row, Manchester, and observed the streams of operatives as they left the mills. The children were almost universally illlooking, small, sickly, barefoot, and ill-clad. Document D Andrew Ure, THE PHILOSOPHY OF MANUFACTURES, 1835 Ill-usage of any kind is a very rare occurrence. I have visited many factories, both in Manchester and in the surrounding districts…and I never saw a single instance of corporal chastisement inflicted on a child, nor indeed did I ever 10 see children in ill-humour. They seemed to be always cheerful and alert, taking pleasure in the light play of their muscles. The scene of industry was always exhilarating. It was delightful to observe the nimbleness with which they pieced the broken ends. The work of these lively elves seemed to resemble a sport, in which habit gave them a pleasing dexterity. As to exhaustion by the day's work, they evinced no trace of it on emerging from the mill in the evening. They immediately began to skip about any neighbouring playground and to commence their little amusements with the same alacrity as boys issuing from a school. They thrive better when employed in our modern factories than if left at home in apartments too often ill-aired, damp, and cold. Document E James Myles, "Dundee Republic of Letters", 1850 About a week after I became a mill boy, I was seized with a strong, heavy sickness, that few escape on first becoming factory workers. The cause of this sickness which is known by the name of 'mill fever', is the pestiferous atmosphere produced by so many breathing in a confined place, together with the heat and exhalations of grease and oil. All these causes are aggravated in the winter time by the immense destruction of pure air by the gas that is needed to light the establishment. This fever does not often lay the patient up. It is slow, dull, and painfully wearisome in its operation. It produces a sallow and debilitated look, destroys rosy cheeks, and unless the constitution be very strong, leaves its pale impress for life. Document F Nassau Senior, Letters on the Factory Act , 1830 The factory work-people in the country districts are the plumpest, best clothed, and healthiest looking persons of the labouring class that I have ever seen. The girls, especially, are far more good-looking (and good looks are fair evidence of health and spirits) than the daughters of agricultural labourers. The wages earned per family are more than double those of the south….Parliament got up a frightful and an utterly unfounded picture of the ill-treatment of the children. Document G John Fielden , THE CURSE OF THE FACTORY SYSTEM, 1836 I well remember being set to work in my father's mill when I was little more than ten years old; my associates, too, in the labour and in recreation are fresh in my memory. Only a few of them are now alive; some dying very young, others living to become men and women; but many of those who live have died off before they attained the age of fifty, having the appearance of being much older, a premature appearance of age which I verily believe was caused by the nature of the employment in which they had been brought up. For several years 11 after I began to work in the mill, the hours of labour in our works did not exceed ten hours. Document H Peter Gaskell, 1833 So long as home education is not found for them, they are to some extent better situated when engaged in light labour, and the labour generally is light which falls to their share. However, the bringing together numbers of the young of both sexes in factories has been a prolific source of moral delinquency. The stimulus of a heated atmosphere, the contact of opposite exes, the example of license upon the animal passions--all have conspired to produce a very early development of sexual appetencies. Document I Abraham Whitehead, clothier, Testimony to Parliament, 1832 I can tell you what a neighbour told me six weeks ago; she is the wife of Jonas Barrowcliffe, near Scholes; her child works at a mill nearly two miles from home, and I have seen that child coming from its work this winter between 10 and 11 in the evening; and the mother told me that one morning this winter the child had been up by two o'clock in the morning, when it had only arrived from work at eleven; it had then to go nearly two miles to the mill, where it had to stay at the door till the overlooker came to open it…They had no clock; and she believed, from what she afterwards learnt from the neighbours, that it was only 2 o'clock when the child was called up and went to work; but this has only generally happened when it has been moonlight, thinking the morning was approaching. Document J: anonymous, A Letter to Parliament on the Factories Bill, 1832 The first and immediate consequence of limiting the ages of children employed, to under 9 years will be to throw out of employment all that class of hands. This is perhaps the most cruel stroke to the poor man which could have been inflicted…this threatened invasion of the rights of the parent over the child is an infringement of the liberty of the subject, and a direct violation of the homes of Englishmen…and the quantity of goods produced in mills and factories will be diminished in direct proportion to the curtailment of the hours of labour. 12 LESSON PLAN FORMAT: The Industrial Revolution in Britain Lesson Topic: # 3 intervention Southey v. Macaulay on the wisdom of government Main Unit Objective: (from the National Standards for History) The students understand the early industrialization and the importance of developments in England. Specific Lesson Objective: (from the National Standards for History) The students will be able to (1) analyze connections between industrialization and movements of reform, (2) understand the arguments of those who believed in laissez-faire principles, and (3) compare and contrast differing sets of ideas and values. Lesson Design: Initiation: In preparation for this lesson, students would be assigned the task of defining the term 'laissez-faire' in their notebook. The teacher would begin class by making sure students understood the concept (3-5 minutes) and then introduce the three student participants for the debate. Main Lesson Activities: Three students would be assigned to roles for this activity. One would be the host of a radio/TV show, one would role-play Robert Southey, and one would role-play Thomas Macaulay. The students would 'perform' in their roles (15-20 minutes), followed by questions and discussion. Closure: The teacher would conclude the class by asking which of the two points of view (Southey or Macaulay) the students most agreed with and why. It might also be appropriate to ask how the points of view were also evident in American political debates today. (10-15 minutes) Resources: Role-play materials. ROLE-PLAY # 1 The host of the radio/TV show: Script Hello--and welcome to England's favorite morning talk show, GOOD MORNING, NOTTINGHAM ! 13 My name is Macro Economics, and I will serve as your host in another of our series of topics on the Industrial Revolution. Other topics we have explored in past shows have been child labor, standard of living controversies, famous inventors and the connection of industrialization with imperialism. Today's discussion will focus on the Role of Government during the Industrial Revolution. That is, should the government by playing a greater role in the affairs of the country by regulating or controlling the economy. Our guests are Robert Southey and Thomas Babington Macaulay, two citizens of Britain who symbolize the on-going debate about the Industrial Revolution. Here is our format: --Each of our guests will make a brief introductory statement. --Each will then present a more detailed statement about their position on the topic. --Finally, we will give each of them the opportunity to exchange views in a more informal manner and to entertain questions from the audience. ROLE-PLAY # 2 Robert Southey OPENING STATEMENT: Good morning. I am Robert Southey, poet laureate of England since 1813. I am proud to be one of the so-called 'lake poets' along with my friends William Wordsworth and Samuel Coleridge. I have written an article on the negative aspects of the Industrial Revolution entitled "Sir Thomas More: Colloquies on the Progress and Prospects of Society." (1829) In this work, I used the literary device of a conversation between a real historical figure from England's past, Sir Thomas More, and a fictional character called Montesino. More, as you will recall, was executed by Henry VIII in the 1530s for defending his religious beliefs. Like More, I have been savagely attacked by Mr. Macaulay, whose ego and narrow-mindedness is like that our obstinate former king. I am here today to respond to Macaulay's charges, although, frankly, I would rather by walking the moors or tending to my roses. POSITION STATEMENT: I strongly believe that our people are worse off than ever before. Our cities are crowded and filthy. The exploitation of children is a national shame. It is, 14 therefore, my belief that our government has a responsibility to do more to help the needy and working poor. It should, for example, provided public work jobs for the unemployed, establish a national system of education under the guidance of the Anglican Church, and assist those who wish to emigrate from England. We cannot presume that progress is evitable. Misery is often the cause of wickedness. Ignorance, vice, crime and poverty are flourishing in what was once the garden of civilization. Many people wake up every morning without knowing how they are to eat or where they will lay their heads at night. Some of our leaders cry about Negro slavery in the colonies but yet are blind to problems here at home. Our problems are such that we must be wary of revolution. The masses of people could appear in the streets. Lava floods from a volcano would be less destructive than the hordes that our great cities and manufacturing districts would vomit forth. Our morals have declined. The desire to gain has eaten into the core of the nation. All men are oppressing their neighbors, preying like wild beasts upon their fellow creatures. Surely, a degree of wholesome restraint and regulation is needed. In conclusion, I feel that a more peaceful and a more beautiful England existed at one time. Weren't people happier and better provided for when the land was open before enclosure? Can we not do something to restore that time--a time of rose bushes and weather-stained cottages, of unspoiled lakes and of a happy and healthy people? I think we can and must, but not with the leaders of the ilk of Mr. Macaulay who is unable or unwilling to see what is happening to dear old England. ROLE-PLAY # 3: Thomas Macaulay OPENING STATEMENT: My name is Thomas Babington Macaulay. I am a lawyer, writer for THE EDINBURGH REVIEW, member of Parliament, colonial official in India, and author of the famous HISTORY OF ENGLAND, which focuses on the Glorious Revolution of 1688. I did indeed write a 37-page review of Mr. Southey's COLLOQUIES in 1830 and found it to be pathetic and laughable. Southey may be a good poet, but he is surely not a good economist or historian. He has no right to lecture the public on economic and political matters of which he has still the very alphabet to learn. I have no idea why Mr. Southey brings Sir Thomas More back to life in his COLLOQUIES. Perhaps this device would be appropriate in a traditional epic poem, but it makes for lousy economics. What I want, Mr. Southey, is facts! In my review and again today, I charge that you do not bring forward a single fact in support of your view. I challenge you to prove that the great and beneficial Industrial Revolution has been a disaster. To my way of thinking, it has brought 15 wonderful progress and prosperity. So, I look forward to our debate this morning. POSITION STATEMENT: As I stated in my introductory comments, I question the source of Mr. Southey's opinion. He surely has not studied bills of mortality or statistical tables. He obviously does not stoop to study the history of the system he abuses or to compare districts or generations. Rather, it seems that Mr. Southey's methodology is this: he stands on a hill to look at a cottage and a factory to decide which is prettier. Does he really think that the English people ever lived in substantial and ornamental cottages with box-hedges, flower gardens, bee-hives and orchards? He believes that a government nears perfection as it interferes more and more with the habits of individuals. I, for one, do not want an omnipresent and omniscient state. I believe that nothing is worse than a meddling government, one that tells people what to read, say, eat, drink and wear. Mr. Southey is a pessimist. He fears revolution instigated by the poor masses, who will invade the streets like volcanic lava. I look, however, on the state of England with much greater hope and satisfaction. Southey asserts that people were better off than before. Perhaps he would have been better suited for the first twenty years of the sixteenth century when More lived. But people are better off now and certainly better off that people in Russia and Poland. The fact is that medicine and medical care is better, that life expectancy is longer, and that we are making more products at lower cost. The serving man, the artisan, and the farmer have more food and better clothing and furniture than their ancestors. Merchants and shopkeepers are richer. We are not, in a word, sir, the wretched of the earth. I am not a prophet, but can anyone deny that in a hundred years--say by 1930-we will be even better fed, clothed and houses? And it is clear that the prudence and energy of our people will continue to carry us forward. In conclusion, in contrast to Mr. Southey, our government should confine itself to its legitimate duties, which are: --leave capital to find its most lucrative course. --leave commodities to find their fair price. --leave industry and intelligence to find their natural reward. --leave idleness and folly to find their natural punishment. --maintain the peace and defend property. --observe strict economy in every department 16 AND THEN, LET THE PEOPLE DO THE REST. Thank you. 17 LESSON PLAN FORMAT: The Industrial Revolution in Britain Lesson Topic: # 4 Descriptions of cities and factories in the Industrial Revolution Main Unit Objective: (from the National Standards for History) The students understand the early industrialization and the importance of developments in England. Specific Lesson Objective: (from the National Standards for History) The students will be able to (1) compare primary sources about a problem and analyze the different perspectives they present and (2) evaluate the quality of life in cities and factories in early 19th century England. Lesson Design: Initiation: In preparation for this lesson, students were assigned four primary sources. (poems by E. Jones and J. Jones, readings by Taylor and Trollope) They were to read and compare the points of view. At the beginning of class, the teacher will organize the students into groups of 2 or 3 to share their work. (10 minutes) Main Lesson Activities: The teacher will then distribute copies of Wordsworth's poem "The Excursion" and ask the groups to compare it with the four sources they already have. Spokespersons from each group will share their reactions. (20 minutes) Closure: The teacher will distribute copies of Blake's poem , ask one student to read it aloud, and then ask students how Blake fits in with the other sources. Resources: copies of primary sources Lesson Plan # 4 Primary sources Document A "The Cotton Mill", John Jones, 1821 Now see the Cotton from the town convey'd To Manchester, that glorious mart of trade: Hail splendid scene! The Nurse of every art, That glads the widow's and the orphan's heart! Thy mills, like gorgeous palaces, arise, And lift their useful turrets to the skies! See Kennedy's stupendous structure join'd To thine M'Connell--friends of human kind! Whose ready doors for ever wide expand To give employment to a numerous band, Murray's behold! That well deserves a name,-And Lee's and Houldsworth's our attention claim,-And numerous others, scattered up and down, The sole supporters of this ample town. Document B "The Factory Town", Ernest Jones, 1847 The night had sunk along the city, It was a bleak and cheerless hour; The wild winds sang their solemn ditty To cold grey wall and blackened tower. The factories gave forth lurid fires From pent-up hells within their breast; E'en Etna's burning wrath expires, But man's volcanoes never rest. Women, children, men were toiling, Locked in dungeons close and black, Life's fast-failing thread uncoiling Round the wheel, the modern rack! E'en the very stars seemed troubled With the mingled fume and roar; The city like a cauldron bubbled, With its poison boiling o'er. For the reeking walls environ 19 Mingled groups of death and life: Fellow-workmen, flesh and iron, Side by side in deadly strife. There, amid the wheels' dull droning And the heavy, choking air, Strength's repining, labour's groaning, And the throttling of despair… Stood the half-naked infants shivering With heart-frost amid the heat; Manhood's shrunken sinews quivering To the engine's horrid beat!… Yet their lord bids proudly wander Stranger eyes thro' factory scenes; 'Here are men, and engines yonder'. 'I see nothing but the machines!'… Thinner wanes the rural village, Smokier lies the fallow plain-Shrinks the cornfields' pleasant tillage, Fades the orchard's rich domain; And a banished population Festers in the fetid street:-Give us, God, to save our nation, Less of cotton, more of wheat. Take us back to lea and wild wood, Back to nature and to Thee! To the child restore the childhood-To the man his dignity. Document C excerpt from THE LIFE AND ADVENTURES OF MICHAEL ARMSTRONG, THE FACTORY BOY, Francis Trollope, 1840 The party entered the building…The ceaseless whirring of a million hissing wheels seizes on the tortured ear; and while threatening to destroy the delicate sense, seems bent on proving first, with a sort of mocking mercy, of how much suffering it can be the cause. The scents that reek around, from oil, tainted water, and human filth, with that last worst nausea, arising from the host refuse of atmospheric air, left by some hundred pairs of labouring lungs, render the act 20 of breathing a process of difficulty, disgust and pain. But what the eye brings home to the heart of those, who look round upon the horrid earthly hell, is enough to make it all forgotten; for who can think of villainous smells, or heed the suffering of the ear-racking sounds, while they look upon hundreds of helpless children, divested of every trace of health, of joyousness, and even of youth! Assuredly there is no exaggeration in this: for except only in their diminutive size, these suffering infants have no trace of it. Lean an distorted limbs--sallow and sunken cheeks--dim hollow eyes, that speak unrest and most unnatural carefulness, give to each tiny trembling, unelastic form, a look of hideous premature old age. Document D "Notes of a Tour in the Manufacturing Districts of Lancashire", W.C. Taylor, 1842 How a painter would have enjoyed the sight which broke upon my waking eyes this morning!…The valley is studded with factories and bleachworks. Thank God, smoke is rising from the loftey chimneys of most of them! For I have not traveled thus far without learning that the absence of smoke from the factory-chimney indicates the quenching of the fire on many a domestic hearth, want of employment to many a willing labourer, and want of bread to many an honest family. The smoke too creates no nuisance here--the chimneys are too far apart; and it produces variations in the atmosphere and sky which, to me at least, have a pleasing and picturesque effect. I visited the interior of Mr. Ashworth's Turton Mill, which does not differ materially from that of many other well-regulated mills which I have visited. I was pleased to find that great care had been bestowed upon the 'boxing up' of dangerous machinery. I learned that accidents were very rare, and that, when they did occur, they were the result of the grossest negligence or of absolute willfulness. I mention this circumstance because the burst of sentimental sympathy for the condition of the factory-operatives which, a few years ago, frightened the isle from its propriety, appealed largely to the number of accidents which happened from machinery, and I was myself for a time fool enough to believe that mills were places in which young children were, by some inexplicable process, ground--bones, flesh, and blood together--into yarn and printed calicoes. I remember very well when first I visited a cotton-mill feeling something like disappointment at not discovering the hoppers into which the infants were thrown. The conditions in the mill are exceedingly favourable. The working rooms are lofty, spacious, and well ventilated, kept at an equable temperature, and scrupulously clean. There is nothing in sight, sound, or smell to offend the most fastidious sense. I should be very well contented to have as large a proportion of 21 room and air in my own study as a cotton-spinner in any of the mills of Lancashire. The toil is not very great, nor is it incessant. The heaviest part of the labour is executed by the steam-engine or water-wheel; and there are so many intervals of rest, that I am under the mark when I assert than an operative in a cotton-factory is at rest one minute out of every three during the period of his nominal employment. Document E excerpt from "The Excursion", William Wordsworth, 1814 Meanwhile, at social Industry's command How quick, how vast an increase. From the germ Of some poor hamlet, rapidly produced Here a huge town, continuous and compact Hiding the face of earth for leagues-and there, Where not a habitation stood before, Abodes of men irregularly massed Like trees in forests,-spread through spacious tracts. O'er which the smoke of unremitting fires Hangs permanent, and plentiful as wreaths Of vapour glittering in the morning sun. And, wheresoe'er the traveler turns his steps He sees the barren wilderness erased, Or disappearing; triumph that proclaims How much the mild Directress of the plough Owes to alliance with these new-born arts! -Hence is the wide sea peopled,-hence the shores Of Britain are resorted to by ships Freighted from every climate of the world With the world's choicest produce. Hence that sum Of keels that rest within her crowded ports Or ride at anchor in her sounds and bays; That animating spectacle of sails That, through her inland regions, to and fro Pass with the respirations of the tide, Perpetual, multitudinous!… …I grieve, when on the darker side Of this great change I look; and there behold Such outrage done to nature as compels The indignant power to justify herself; Yea, to avenge her violated rights. For England's bane. Document F "And Did Those Feet In Ancient Time", William Blake, 1808 22 And did those feet in ancient time Walk upon England's mountains green? And was the Holy Lamb of God On England's pleasant pastures seen? And did the Countenance Divine Shine forth upon our clouded hills? And was Jerusalem builded here Among these dark Satanic mills? Bring me my bow of burning gold: Bring me my arrows of desire: Bring me my spear: O clouds unfold! Bring me my chariot of fire. I will not cease from mental fight, Nor shall my sword sleep in my hand Till we have built Jerusalem In England's green and pleasant land. 23 LESSON PLAN FORMAT: The Industrial Revolution in Britain Lesson Topic: # 5 Idleness as a Vice: Values during the Industrial Revolution Main Unit Objective: (from the National Standards for History) The students understand the early industrialization and the importance of developments in England. Specific Lesson Objective: (from the National Standards for History) The students will be able to (1) explain how industrialization affected the daily live of men, women and children, (2) describe the attitudes towards the concept of 'idleness', and (3) analyze primary sources for the information they reveal. Lesson Design: Initiation: In preparation for this lesson, students will be assigned three primary sources (A, B, C) that deal with the concept of 'idleness'. They are to compare the three sources by writing similarities and differences in their notebooks. At the beginning of class, the teacher will organize the students in groups of 2 or 3 for the purpose of sharing homework comparisons. (10 minutes) Main Lesson Activities: The teacher will distribute copies of Hogarth's entitled "Industry and Idleness". In groups, students will be instructed to (1) list all the details in the picture and (2) explain what Hogarth is trying to show. (15 minutes) Closure: The teacher will (1) ask students to compare Hogarth's print with the articles that they read and (2) read a brief selection of Smiles' SELFHELP--and ask: What is the similarity between Smiles and Hogarth? How would factory owners feel about these two sources? (10-15 minutes) Resources: primary sources Lesson # 5: Primary Sources Document A: "The Farmer's Tour Through the East of England", Arthur Young, 1771 The weaving man and his boy, who now earn in general 7s. a week, could earn with ease 11s. if industrious. But it is remarkable, that those men and their families who earn but 6s. a week, are much happier and better off than those who earn 2s. or 3s. extraordinary; such extra earnings are mostly spent at the alehouse, or in idleness, which prejudice their work. This is precisely the same effect as they have found when the prices of provisions have been very cheap; it results from the same cause. And this city (Norwich) has been very often pestered with mobs and insurrections under the pretence of an high price of provisions, merely because such dearness would not allow the men that portion of idleness and other indulgence which the low rates throw them into. Document B: "A Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain", Daniel Defoe, 1724 The whole country is full of people near Halifax. Those people all full of business; not a beggar, not an idle person to be seen, except here and there an alms-house, where people antient, decrepid and past labour, might perhaps be found; for it is observable, that the people here, however labourious, generally live to a great age, a certain testimony to the goodness and wholesomeness of the country…Among the manufacturers houses are likewise scattered an infinite number of cottages in which dwell the workmen who are employed, the women and children of whom, are always busy carding, spinning, etc. so that no hands being unemploy'd, all can gain their bread. This is the reason also why we saw so few people without doors; but if we knock'd at the door of any of the master manufacturers, we presently saw a house full of lusty fellows, some at the dyefact, some dressing the cloths, some in the loom, some one thing, some another, all hard at work, and full employed upon the manufacture, and all seeming to have sufficient business. Document C: "The Weaver's Pocket- Book", 1766, anonymous Once more, methinks I cannot but observe, how the wisdom of divine providence hath made work for all the children of men…That we are full of scandalous beggars, is not because the providence of God hath not laid out work enough…but because parents are suffered to bring up children in idleness. O England! Spit out they flegm, shake off thy sloth, honour God in the substance and increase which he hath given thee. It is nothing but lust and sloth that fills 25 thee with such prodigious wickedness and beggary…an advantage of work is the little time it giveth for idleness. Idleness (especially in youth) is the source and fountain of almost all the debauchery that polluteth the world, and all the beggary with which we abound…It is the idle person that proves the gamester, the drunkard…the lesser the time for idleness any trade allows, the better it is. Document D: see Hogarth's print Document E: SELF-HELP, Samuel Smiles, 1859 [This book sold 20,000 copies in the first year, 55,000 by 1864, 150,000 by 1889, and about a quarter of a million by the time of Smile's death in 1904.] 'Heaven helps those who help themselves' is a well-tried maxim, embodying in a small compass the results of vast human experience. The spirit of self-help is the root of all genuine growth in the individual; and it constitutes the true source of national vigour and strength. Help from without is often enfeebling in its effects, but help from within invariably invigorates. Whatever is done for men or classes, to a certain extent takes away the stimulus and necessity of doing for themselves; and where men are subjected to over-guidance and over-government, the inevitable tendency is to render them comparatively helpless…the value of legislation as an agent in human advancement has always been greatly over-estimated…[legislation] can exercise but little active influence upon any man's life and character…the function of government is the protection of life, liberty and property…But there is no power of law that can make the idle man industrious, the thriftless provident, or the drunken sober; though every individual can be each and all of these if he will, by the exercise of his own free powers of action and self-denial. 26