1.3.6.3. Designing Genes for Insertion

advertisement

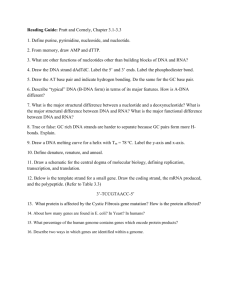

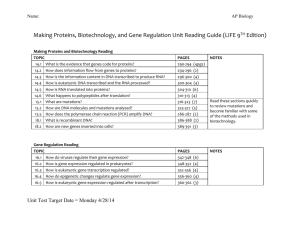

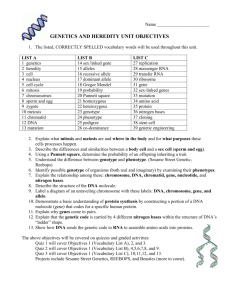

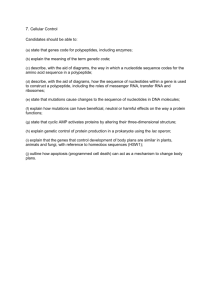

1. TECHNOLOGY OF GENETICALLY MODIFIED FOODS 1.1. What is GM GM, which can stand for genetic modification or genetically modified, is the technique of changing or inserting genes. Genes carry the instructions for all the characteristics that an organism – a living thing – inherits. They are made up of DNA. Genetic modification is done either by altering DNA or by introducing genetic material from one organism into another organism, which can be a variety of either the same or a different species. For example, genes can be introduced from one plant to another plant, from a plant to an animal, or from an animal to a plant. Transferring genes between plants and animals is a particular area of debate. Sometimes the term ‘biotechnology’ is used to describe genetic modification. This also has a wider meaning of using microorganisms or biological techniques to process waste or produce useful compounds, such as vaccines. Throughout this booklet the abbreviation ‘GM’ will be used to stand for ‘genetically modified’. Genetic technique is the amount of techniques to promote the transmission of hereditary material between living organism. Genetic modification has been used for 10,000 years, since agriculture began at the end of the last ice age. However, the term has more recently come to be used for the process of 'genetic engineering', where newly developed processes of molecular biotechnology are employed to insert relatively few genes into an organism's genome. GM using the new technologies is distinguished from GM using traditional techniques by referring to the former as the ‘new GM’. There are at least three traditional methods of genetic modification: a) Selecting for variability within existing populations, derived mainly from genetic recombination. It is noteworthy that most modern crops have been so altered using primarily this technique that it is difficult to identify their wild progenitors. b) Crossing closely related species. For example, modern bread wheat has arisen from two sequential crossings of, in total, three species, accompanied by two chromosome doubling events. 1 c) Isolating mutants. For example, herbicide resistant oilseed rape has been developed from plants that appeared spontaneously in Canadian fields. In addition to these traditional approaches, there is the new GM, involving the modification of specific genes in single cells using recently developed biotechnologies. Essentially, this process involves: 1) The identification and isolation of one or more genes that will direct the synthesis of proteins with particular desirable characteristics. 2) The movement of the desired gene(s) into another organism. Genes are usually moved into other organisms by exploiting natural pathogens whose mode of infection involves the injection into the host of genetic material. This gene transfer occurs into a single cell. 3) An entire plant must be regenerated from the single transformed cell. Thus, transfer into ovules or single-celled embryos is technically desirable, as these are programmed for growth into a multicellular organism. Totipotency, whereby cells from the adult plant have the ability to regenerate into new adults, is, of course, particularly useful in higher plants, as a range of cell types can be used for gene manipulations. Traditional techniques for gene modification limited modifications to those occurring between closely related organisms. The new GM can be used for similar types of gene modifications, but it also enables the transfer of genes between any two organisms (including between a plant and an organism. Thus, although the new GM enables the addition to a crop's genome of just one gene, with a specific trait (unlike traditional breeding programmes, where thousands of genes are transferred at a time), the one gene could come from any organism, or even be created de novo in the laboratory. Overall, the new GM tends to bring in fewer genes, but potentially from further away (evolutionarily), compared to the old GM. Genetic technique is a very young science; in 1973 genes where transfered for the first time from one bacterium to another and later on, in 1977 the soil bacterium Agrobacterium tumefaciens was used to transfer alien genes into the cell of plants, or the Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) has introduced proteins in bt-Maize. The antisense 2 technique indexAntisense technique was developed in 1990. It suppresses some genes, This was used modifying tomato FlavrSavr. The gene producing ripening enzymes is suppressed and the tomato has a long shelf life. Genetic engineering is the technique of removing, modifying or adding genes to a DNA molecule in order to change the information it contains. By changing this information, genetic engineering changes the type or amount of proteins an organism is capable of producing. Genetic engineering is used in the production of drugs, human gene therapy, and the development of improved plants. 1.2. What is biotechnology Although "biotechnology" and "genetic modification" commonly are used interchangeably, GM is a special set of technologies that alter the genetic makeup of such living organisms as animals, plants, or bacteria. Biotechnology, a more general term, refers to using living organisms or their components, such as enzymes, to make products that include wine, cheese, beer, and yogurt. Contrary to its name, biotechnology is not a single technology. Rather it is a group of technologies that share two (common) characteristics -- working with living cells and their molecules and having a wide range of practice uses that can improve our lives. Biotechnology can be broadly defined as "using organisms or their products for commercial purposes." As such, (traditional) biotechnology has been practices since he beginning of records history. (It has been used to:) bake bread, brew alcoholic beverages, and breed food crops or domestic animals. But recent developments in molecular biology have given biotechnology new meaning, new prominence, and new potential. It is (modern) biotechnology that has captured the attention of the public. Modern biotechnology can have a dramatic effect on the world economy and society. 3 One example of modern biotechnology is genetic engineering. Genetic engineering is the process of transferring individual genes between organisms or modifying the genes in an organism to remove or add a desired trait or characteristic. Through genetic engineering, genetically modified crops or organisms are formed. These GM crops or GMOs are used to produce biotech-derived foods. It is this specific type of modern biotechnology, genetic engineering, that seems to generate the most attention and concern by consumers and consumer groups. 1.3. What is DNA All organisms are made up of cells that are programmed by the same basic genetic material, called DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid). Each unit of DNA is made up of a combination of the following nucleotides -- adenine (A), guanine (G), thymine (T), and cytosine (D) -- as well as a sugar and a phosphate. These nucleotides pair up into strands that twist together into a spiral structure call a "double helix." This double helix is DNA. Segments of the DNA tell individual cells how to produce specific proteins. These segments are genes. It is the presence or absence of the specific protein that gives an organism a trait or characteristic. More than 10,000 different genes are found in most plant and animal species. This total set of genes for an organism is organized into chromosomes within the cell nucleus. The process by which a multicellular organism develops from a single cell through an embryo stage into an adult is ultimately controlled by the genetic information of the cell, as well as interaction of genes and gene products with environmental factors. Locating genes for important traits—such as those conferring insect resistance or desired nutrients—is one of the most limiting steps in the process. However, genome sequencing and discovery programs for hundreds of different organisms are generating detailed maps along with data-analyzing technologies to understand and use them. For the earliest geneticists, genes were fairly distinct traits or characteristics which could be observed in the whole organism. For the modern molecular biologist or molecular geneticist a more chemical definition of a gene is used which brings in a 4 number of additional concepts. The molecular gene is a definite sequence of bases in the DNA chain which together code for the production of a particular protein. The above diagram is an artist's symbolic impression using a false perspective of structures supposed to be present on a microscopic and molecular scale. The expert would notice that the diagram shows a great deal of artistic license. Nobody knows what these structures actually 'look' like in a living organism. Organisms are made up of single cells. The figure shows at the top a cross-section of a typical cell from an animal. At the centre of the cell is a nucleus which contains nearly all the genetic material. This genetic material is 'packaged' into organised structures called chromosomes, named after the way they take up coloured stain when prepared for examination by light microscopy at a particular stage of the cell's cycle of growth and reproduction. The diagram shows a chain of DNA (desoxyribosenucleic acid) unravelling out of one of the chromosomes. Note its double helical geometric structure shown as two intertwining ribbons. Lying between the two backbones of the double-helix are chemical substances known as bases: guanine (G), thymine (T), cytosine (C) and adenine (A). Through the chemical nature of the bases they pair up with each other in the following specific way: G with C, and T with A. 5 The process of genetic engineering is known by many different names such as gene, or DNA manipulation, gene splicing, transgenics and many others. However the underlying processes all have the same aim and that is: "To isolate single genes of a known function from one organism and transfer a copy of that gene to a new host to introduce a desirable characteristic" Scientists are able to extract DNA from any organism and can then isolate a specific gene through the use of restriction endonucleases, which cut DNA strands at specific points. The gene is then copied billions fold in readiness for transfer to another organism. Fig. 1 The structure of DNA as a double helix with the phosphate backbone in yellowgreen and the bases in white or teal green. The blue and red figures represent the 3-D structure of a restriction enzyme (EcoR1) which recognizes and cuts the DNA at a specific region of the DNA. Other enzymes known as ligases join the ends of two DNA fragments. These and other enzymes enable the manipulation and amplification of DNA, essential components in joining the DNA of two unrelated organisms. 1.3.1. Restriction Enzymes Restriction enzymes are DNA-cutting enzymes found in bacteria (and harvested from them for use). Because they cut within the molecule, they are often called restriction endonucleases. 6 A restriction enzyme recognizes and cuts DNA only at a particular sequence of nucleotides. For example, the bacterium Hemophilus aegypticus produces an enzyme named HaeIII that cuts DNA wherever it encounters the sequence 5'GGCC3' 3'CCGG5' The cut is made between the adjacent G and C. This particular sequence occurs at 11 places in the circular DNA molecule of the virus phiX174. Thus treatment of this DNA with the enzyme produces 11 fragments, each with a precise length and nucleotide sequence. These fragments can be separated from one another and the sequence of each determined. HaeIII and AluI cut straight across the double helix producing "blunt" ends. However, many restriction enzymes cut in an offset fashion. The ends of the cut have an overhanging piece of single-stranded DNA. These are called "sticky ends" because they are able to form base pairs with any DNA molecule that contains the complementary sticky end. Any other source of DNA treated with the same enzyme will produce such molecules. 7 Mixed together, these molecules can join with each other by the base pairing between their sticky ends. The union can be made permanent by another enzyme, DNA ligase, that forms covalent bonds along the backbone of each strand. The result is a molecule of recombinant DNA (rDNA). The ability to produce recombinant DNA molecules has not only revolutionized the study of genetics, but has laid the foundation for much of the biotechnology industry. The availability of human insulin (for diabetics), human factor VIII (for males with hemophilia A), and other proteins used in human therapy all were made possible by recombinant DNA.. 1.3.2. Nucleotides Nucleic acids are linear, unbranched polymers of nucleotides. Nucleotides consist of three parts: 1. A five-carbon sugar (hence a pentose). Two kinds are found: Deoxyribose, which has a hydrogen atom attached to its #2 carbon atom (designated 2') Ribose, which has a hydroxyl group atom there Deoxyribose-containing nucleotides, the deoxyribonucleotides, are the monomers of DNA. Ribose-containing nucleotides, the ribonucleotides, are the monomers of RNA. 8 2.A nitrogen-containing ring structure called a base. The base is attached to the 1' carbon atom of the pentose. In DNA, four different bases are found: 1. two purines, called adenine (A) and guanine (G) 2. two pyrimidines, called thymine (T) and cytosine (C) RNA contains: The same purines, adenine (A) and guanine (G). RNA also uses the pyrimidine cytosine (C), but instead of thymine, it uses the pyrimidine uracil (U). 1.3.3. The Purines & Pyrimidines Pyrimidine Purine 9 The combination of a base and a pentose is called a nucleoside. 3.One (as shown in the first figure), two, or three phosphate groups. These are attached to the 5' carbon atom of the pentose. Both DNA and RNA are assembled from nucleoside triphosphates. For DNA, these are dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP. For RNA, these are ATP, CTP, GTP, and UTP. In both cases, as each nucleotide is attached, the second and third phosphates are removed. The nucleosides and their mono-, di-, and triphosphates Base Nucleoside Nucleotides Adenine (A) Deoxyadenosine dAMP dADP dATP DNA Guanine (G) Deoxyguanosine dGMP dGDP dGTP Cytosine (C) Deoxycytidine dCMP dCDP dCTP Thymine (T) Deoxythymidine dTMP dTDP dTTP RNA Adenine (A) Adenosine AMP ADP ATP Guanine (G) Guanosine GMP GDP GTP Cytosine (C) Cytidine CMP CDP CTP Uracil (U) UMP UDP UTP Uridine 1.3.4. Base Pairing 10 The rules of base pairing (or nucleotide pairing) are: A with T: the purine adenine (A) always pairs with the pyrimidine thymine (T) C with G: the pyrimidine cytosine (C) always pairs with the purine guanine (G) This is consistent with there not being enough space (20 Å) for two purines to fit within the helix and too much space for two pyrimidines to get close enough to each other to form hydrogen bonds between them. Only with A & T and with C & G are there opportunities to establish hydrogen bonds (shown here as dotted lines) between them (two between A & T; three between C & G). These relationships are often called the rules of Watson-Crick base pairing, named after the two scientists who discovered their structural basis. The rules of base pairing tell us that if we can "read" the sequence of nucleotides on one strand of DNA, we can immediately deduce the complementary sequence on the other strand. The rules of base pairing explain the phenomenon that whatever the amount of adenine (A) in the DNA of an organism, the amount of thymine (T) is the same (called Chargaff's rule). Similarly, whatever the amount of guanine (G), the amount of cytosine (C) is the same. Relative Proportions (%) of Bases in DNA Organism A T G C Human 30.9 29.4 19.9 19.8 Chicken 28.8 29.2 20.5 21.5 Grasshopper 29.3 29.3 20.5 20.7 Sea Urchin 32.8 32.1 17.7 17.3 Wheat 27.3 27.1 22.7 22.8 Yeast 31.3 32.9 18.7 17.1 E. coli 24.7 23.6 26.0 25.7 11 1.3.5. The Double Helix: The double helix of DNA has these features: It contains two polynucleotide strands wound around each other. The backbone of each consists of alternating deoxiribose and phosphate groups. The phosphate group bonded to the 5' carbon atom of one deoxyribose is covalently bonded to the 3' carbon of the next. The two strands are "antiparallel"; that is, one strand runs 5′ to 3′ while the other runs 3′ to 5′. The DNA strands are assembled in the 5′ to 3′ direction and, by convention, we "read" them the same way. The purine or pyrimidine attached to each deoxyribose projects in toward the axis of the helix. Each base forms hydrogen bonds with the one directly opposite it, forming base pairs (also called nucleotide pairs). 3.4 Å separate the planes in which adjacent base pairs are located. The double helix makes a complete turn in just over 10 nucleotide pairs, so each turn takes a little more (35.7 Å to be exact) than the 34 Å shown in the diagram. There is an average of 25 hydrogen bonds within each complete turn of the double helix providing a stability of binding about as strong as what a covalent bond would provide. The diameter of the helix is 20 Å. The helix can be virtually any length; when fully stretched, some DNA molecules are as much as 5 cm (2 inches!) long. The path taken by the two backbones forms a major (wider) groove (from "34 A" to the top of the arrow) and a minor (narrower) groove (the one below). 12 The identity of a gene and the function it performs are determined by the number of nucleotides and the particular order in which they are strung together on chromosomes – this is known as the ‘sequence’ of the gene. Chromosomes are the structures in cells that carry DNA. 1.3.6. Gene Expression: Transcription: The majority of genes are expressed as the proteins they encode. The process occurs in two steps: Transcription = DNA → RNA Translation = RNA → protein Taken together, they make up the "central dogma" of biology: DNA → RNA → protein. Here is an overview. 13 1.3.6.1. Gene Transcription: DNA → RNA DNA serves as the template for the synthesis of RNA much as it does for its own replication. The Steps: Some 50 different protein transcription factors bind to promoter sites, usually on the 5′ side of the gene to be transcribed. An enzyme, an RNA polymerase, binds to the complex of transcription factors. Working together, they open the DNA double helix. The RNA polymerase proceeds down one strand moving in the 3′ → 5′ direction. In eukaryotes, this requires — at least for protein-encoding genes — that the nucleosomes in front of the advancing RNA polymerase (RNAP II) be removed. A complex of proteins is responsible for this. The same complex replaces the nucleosomes after the DNA has been transcribed and RNAP II has moved on. As the RNA polymerase travels along the DNA strand, it assembles ribonucleotides (supplied as triphosphates, e.g., ATP) into a strand of RNA. Each ribonucleotide is inserted into the growing RNA strand following the rules of base pairing. Thus for each C encountered on the DNA strand, a G is inserted in the RNA; for each G, a C; and for each T, an A. However, each A on the DNA guides the insertion of the pyrimidine uracil (U, from uridine triphosphate, UTP). There is no T in RNA. Synthesis of the RNA proceeds in the 5′ → 3′ direction. As each nucleoside triphosphate is brought in to add to the 3′ end of the growing strand, the two terminal phosphates are removed. When transcription is complete, the transcript is released from the polymerase and, shortly thereafter, the polymerase is released from the DNA. At any place in a DNA molecule, either strand may be serving as the template; that is, some genes "run" one way, some the other (and in a few remarkable cases, the same segment of double helix contains genetic information on both strands!). In all cases, however, RNA polymerase proceeds along a strand in its 3′ → 5′ direction. 14 1.3.6.1.1. Types of RNA Several types of RNA are synthesized: messenger RNA (mRNA). This will later be translated into a polypeptide. ribosomal RNA (rRNA). This will be used in the building of ribosomes: machinery for synthesizing proteins by translating mRNA. transfer RNA (tRNA). RNA molecules that carry amino acids to the growing polypeptide. small nuclear RNA (snRNA). DNA transcription of the genes for mRNA, rRNA, and tRNA produces large precursor molecules ("primary transcripts") that must be processed within the nucleus to produce the functional molecules for export to the cytosol. Some of these processing steps are mediated by snRNAs. small nucleolar RNA (snoRNA). These RNAs within the nucleolus have several functions (described below). microRNA (miRNA). These are tiny (~22 nts) RNA molecules that appear to regulate the expression of messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules. 1.3.6.1.2. RNA Processing: pre-mRNA → mRNA All the primary transcripts produced in the nucleus must undergo processing steps to produce functional RNA molecules for export to the cytosol. We shall confine ourselves to a view of the steps as they occur in the processing of pre-mRNA to mRNA. 15 The steps: Synthesis of the cap. This is a modified guanine (G) which is attached to the 5′ end of the pre-mRNA as it emerges from RNA polymerase II (RNAP II). The cap protects the RNA from being degraded by enzymes that degrade RNA from the 5′ end. Step-by-step removal of introns present in the pre-mRNA and splicing of the remaining exons. This step is required because most eukaryotic genes are split. It takes place as the pre-mRNA continues to emerge from RNAP II. Synthesis of the poly(A) tail. This is a stretch of adenine (A) nucleotides. When a special poly(A) attachment site in the pre-mRNA emerges from RNAP II, the transcript is cut there, and the poly(A) tail is attached to the exposed 3′ end. This completes the mRNA molecule, which is now ready for export to the cytosol. (The remainder of the transcript is degraded, and the RNA polymerase leaves the DNA.) As a summary; genes are discrete segments of DNA that encode the information necessary for assembly of a specific protein. The proteins then function as enzymes to catalyze biochemical reactions, or as structural or storage units of a cell, to contribute to expression of a plant trait. The general sequence of events by which the information encoded in DNA is expressed in the form of proteins via an mRNA intermediary is shown in the diagram below. The transcription and translation processes are controlled by a complex set of regulatory mechanisms, so that a particular protein is produced only when and where it is needed. Even species that are very different have similar mechanisms for converting 16 the information in DNA into proteins; thus, a DNA segment from bacteria can be interpreted and translated into a functional protein when inserted into a plant. 1.3.6.2. Locating Genes for Plant Traits Identifying and locating genes for agriculturally important traits is currently the most limiting step in the transgenic process. It is still known relatively little about the specific genes required to enhance yield potential, improve stress tolerance, modify chemical properties of the harvested product, or otherwise affect plant characters. Usually, identifying a single gene involved with a trait is not sufficient; scientists must understand how the gene is regulated, what other effects it might have on the plant, and how it interacts with other genes active in the same biochemical pathway. Public and private research programs are investing heavily into new technologies to rapidly sequence and determine functions of genes of the most important crop species. These efforts should result in identification of a large number of genes potentially useful for producing transgenic varieties. 1.3.6.3. Designing Genes for Insertion Once a gene has been isolated and cloned (amplified in a bacterial vector), it must undergo several modifications before it can be effectively inserted into a plant. Simplified representation of a constructed transgene, containing necessary components for successful integration and expression. A promoter sequence must be added for the gene to be correctly expressed (i.e., translated into a protein product). The promoter is the on/off switch that controls when and where in the plant the gene will be expressed. To date, most promoters in transgenic crop varieties have been "constitutive", i.e., causing gene expression throughout the life cycle of the plant in most tissues. The most commonly used constitutive promoter is CaMV35S, from the cauliflower 17 mosaic virus, which generally results in a high degree of expression in plants. Other promoters are more specific and respond to cues in the plant's internal or external environment. An example of a light-inducible promoter is the promoter from the cab gene, encoding the major chlorophyll a/b binding protein. Sometimes, the cloned gene is modified to achieve greater expression in a plant. For example, the Bt gene for insect resistance is of bacterial origin and has a higher percentage of A-T nucleotide pairs compared to plants, which prefer G-C nucleotide pairs. In a clever modification, researchers substituted A-T nucleotides with G-C nucleotides in the Bt gene without significantly changing the amino acid sequence. The result was enhanced production of the gene product in plant cells. The termination sequence signals to the cellular machinery that the end of the gene sequence has been reached. A selectable marker gene is added to the gene "construct" in order to identify plant cells or tissues that have successfully integrated the transgene. This is necessary because achieving incorporation and expression of transgenes in plant cells is a rare event, occurring in just a few percent of the targeted tissues or cells. Selectable marker genes encode proteins that provide resistance to agents that are normally toxic to plants, such as antibiotics or herbicides. As explained below, only plant cells that have integrated the selectable marker gene will survive when grown on a medium containing the appropriate antibiotic or herbicide. As for other inserted genes, marker genes also require promoter and termination sequences for proper function. 18