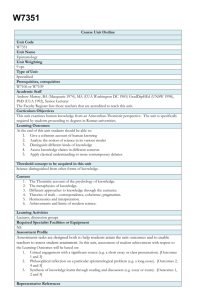

What to do in epistemology

advertisement

What to do with epistemology Federico Pailos A metaphilosophy and its consequences What makes of an idea a good philosophical idea? Or, more specifically: what is the right criterion to evaluate philosophical thesis? One answer could be the following, an insight that Bilgrami seems to have read in Wittgenstein: philosophy must bear certain restrictions in order to avoid confusions, distortions and misrepresentations. If this is so, it would be very useful to acquire a way of limiting the appearance of confusions and misrepresentations. One possible way to do this could be the commitment tot the following restrictive principle: nothing that doesn’t make a difference in practice must make a difference in philosophy. It is inferred from this that whenever a concept lacks a counterpart in the relevant practice, it is not justified. Let’s move now to a certain particular philosophical discipline: epistemology. Which is the relevant practice that would legitimize good epistemological theses? Bilgrami answers: inquiry, and by ‘inquiry’ he refers (he must be referring, as we will see later) to scientific investigation. The justification of this assertion seems reasonable: the only practice unquestionably producing knowledge is scientific research (strictly speaking, the theories resulting from it). Bilgrami rules out as ‘relevant epistemological practice’ the common sensical mental ‘assertive’ states associated to ‘ordinary talk’, because it isn’t clear whether we find knowledge in that sphere. He also rules out philosophical practice as a source of knowledge, that is to say, as a practice relevant to epistemology. With that criterion in mind, Bilgrami underlines the unsatisfactory character of some of the epistemological theses presented by Davidson and Rorty. In particular, Bilgrami objects two davidsonian or rortian conclusions: (1) truth is neither a goal nor a norm of inquiry; (2) we can never tell which of our beliefs is true. Let’s begin with Bilgrami’s rejection of (1). The thesis (1) asserts that the norm compelling inquirers to reach as many truths as one can, and to accept as part of his world’s theory only true propositions, doesn’t make any difference from the norm compelling to search as many justified propositions as one can, and to accept as part of one’s world’s theory only justified propositions. If this is a correct epistemological thesis, it should have a reflection in the relevant practice, that is to say, in what inquirers do and believe. And Bilgrami points out that this is not the case. Inquirers make a difference between propositions that they accept as firmly established, and those which aren’t yet so firmly established, which still admit doubts about their status. The first ones are called ‘truths’. The lasts ones are only hypotheses. How do you evaluate hypotheses? By way of the set of well established propositions. Beliefs are mental ‘assertive’ states directed to firmly established propositions. The set of believed propositions constitutes our global theory, our theory of the world. Truth, then, is a norm of inquiry, that is, a norm of scientific empirical investigation. If our epistemology doesn’t reflect this fact, then it isn’t as good as it could be. If our epistemology denies this fact, as Davidson’s and Rorty’s epistemology does, then it is a bad epistemology. Let’s move to the other assertion that Davidson and Rorty make: we can never tell which of our beliefs is true. Bilgrami maintains that Davidson is forced to make this move because of his defense of what Bilgrami calls ‘the objectivity of truth’: the idea that the truth of a proposition doesn’t depend on any interesting aspect of any kind of epistemic relations in which the proposition could be involved. The idea that we can never tell of any particular empirical proposition that it is true is, according to Bilgrami, a bad idea. And it is a bad idea because it doesn’t have a counterpart in the relevant practice, in empirical inquiry: inquirers don’t admit any doubt about those propositions which are part of their theory of the world. Bilgrami doesn’t deny that all empirical propositions have the logical possibility of being false. But that idea doesn’t play any role in inquiry, nor determines any specific doubt for inquirers in the beliefs constituting their world’s theory. So we must reject the alleged justification of this idea. What can be said once we accept that metaphilosophy. If we accept the metaphilosophical norm that Bilgrami proposes, then we can have some objections to Bilgrami -objections that could be not that interesting. (I) we could ask, for example, justification for the idea that empirical beliefs have the logical possibility of being false. If every epistemological concept of the thesis must have a counterpart in empirical inquiry, and this idea doesn’t have it: what is then its justification? An answer that Bilgrami may give is this: that idea is not part of a good epistemology. Which is its justification, then? It is not an epistemological thesis, but it is a philosophical nonepistemological assertion. It does have a counterpart in a certain relevant practice: the logical practice. Logic qualifies every proposition which is neither true nor false just by the meanings of its concepts, as possibly true and possibly false. Fallibilism is a good philosophical idea, and it belongs to the philosophy of logic. (II) Another objection: it seems reasonable to accept that propositions constituting our own theory of the world are taken by inquirers as true, but also as justified. They think they have good reasons for admitting them in their global theory. If this is the case, then inquirers doesn’t make a difference between true and justified beliefs. So: what is the basis for distinguishing them in epistemology, as Bilgrami does? But Bilgrami thinks that there is a good reason to distinguishing between truth and justification. And he finds that reason in the process of belief revision. As a result of that process, some beliefs constituting our world’s theory ceases to be part of it. Those processes can have good or bad results. Bilgrami thinks that an adequate and intuitive name for good revision processes is ‘justified processes’. Justification is a property of changes of belief, and not of beliefs itself. Attributing justification to beliefs is therefore not counterintuitive, but it provokes confusions, because it is difficult to get a clear idea of what exactly is that strange property possessed by both beliefs and changes of beliefs. It is a much more straightforward option to distinguish justification from truth. What can be said once we reject that metaphilosophy. Several questions arise when Bilgrami’s metaphilosophical norm is examined. The first one is: what is the right way to determine which is the relevant epistemological practice? We may think that this is not a good way of pondering over the issue. First we have the practice and then we produce a philosophical theory to explain it (or to describe it, or to explicit its norms, or to whatever you think a philosophical theory should do). So first we have empirical inquiry, and not formal inquiry nor ordinary talk. (If we had formal inquiry, then the idea that all empirical beliefs can be false would be a good idea, and, as we have seen, it is not.) Why restrict ourselves to make a philosophical theory about empirical inquiry and only about that sort of inquiry? Well, because we want to do that and not other things. The problem with this assertion is why we should call this discipline ‘epistemology’, and not ‘philosophy of empirical inquiry’. Epistemology should focus on knowledge, and some people might defend the idea that formal (mathematical or logical) knowledge exists, and epistemology should refer to it as well as it refers to empirical knowledge. Others might think that you can find knowledge in common sense (that lets us know, for example, that this is my hand, or that there are more than 10 human beings in the world), or in (other disciplines of) philosophy, and so epistemology should refer to them as well. Other people might claim that not all empirical inquiry provides us with knowledge; for example, this people could argue that only physics provides real knowledge. What is then the correct way of distinguishing the relevant epistemological practice, and thus determine that that practice is empirical inquiry? Bilgrami doesn’t give us this norm. Bilgrami’s position sustains another metaphilosophical norm. That norm claims that we must accept only those philosophical theses which are most useful. Bilgrami thinks his epistemology is the most useful for it produces fewer confusions and misrepresentations than any other different epistemology. And it respects a bigger number of important intuitions: it follows from Bilgrami’s epistemology that truth is a goal and a norm of inquiry, and that we can tell of a number of specific beliefs that they are true. And it explains in the most satisfactory way the process of belief change. The only disadvantage of this position is that it implies the counterintuitive claim of denying the objectivity of truth. But Bilgrami argues that a true proposition corresponds to our world view, and that accepting the objectivity of truth forces to renounce to the advantages mentioned before. In particular, the Davidson-Rorty position looses truth as a goal of inquiry, and claims that we can never tell which of our beliefs is true, two important counterintuitive propositions. Rorty disagrees with Bilgrami here. He argues that it is not clear that the most useful standpoint is the one that respects the higher number of important intuitions and desires of most of the inquirers at a certain point and a certain community. This standpoint favors the status quo and discourages new ideas, theories and concepts, leaving aside traditional positions. With this idea of what is useful, Descartes’ ideas would never have had a place (displacing the tomist ideas, popular at that time) , and a similar thing could be said of Kant’s ideas (counter-intuitive when formulated) and of Hegel’s ideas (counter-intuitive at Hegel’s time). This norm cannot be a correct norm to assess the disputes between more traditional positions, as Bilgrami’s, and other non-traditional positions, as Rorty’s. Rorty himself can argue that his ideas make a difference in a future community, in some specific epistemic community better than the present one. What is the reason for relativizing usefulness to the opinion of the actual community, and not to the opinion of a better epistemic community? Actual counterintuitive theses might make a difference in long term practices. Besides, Rorty can claim that his position only argues that when he says that we cannot tell which of our beliefs is true, this only means that we cannot be sure of which of our beliefs is true. But we can and do certainly know of many particular propositions that they are true, and we can know that we know that many particular beliefs are true, because knowledge is just true justified belief, and doesn’t demand any kind of certainty. Rorty’s position is a fallibilist one, which nowadays is an intuitive position, while its negation is not. Bilgrami denies fallibilism, and that makes it, in Bilgrami’s terms, a less useful position, and so a bad epistemology (this is an internal critic). A similar thing can be said of the fact that Rorty’s position doesn’t separate the entities that admit justification from those that admit truth, and Bilgrami’s position does separate them. This is counter-intuitive, and that is not a virtue, according to Bilgrami’s criterion. All this define two different ways of thinking what should be the philosophical practice. One way thinks philosophy as not exceeding the actual practice, trying to reflect it in the theory. This is Bilgrami’s conception. The other one sees philosophy as a way of modifying practices as a way of developing more useful practices. This is how Rorty sees philosophy, and this conception might lead to rebut actually held beliefs and desires (as the desire of answering the esceptic, as the belief that we can tell which of our beliefs are true). One might think that a better metaphilosophical norm is the one that combines the two mentioned above: a good philosophical thesis is the one that makes a difference in a useful practice. This norm allows us to illuminate what is a useful belief (and constitutes a way of answering to those who say that the ‘useful’ norm is not clear, or that it is confused, or that it is not useful), and besides it is not a conservative criterion, as the one defended by Bilgrami. This norm provides philosophy with more freedom to create new vocabularies, not limiting philosophers to an explicative work.