Building Concept Maps

advertisement

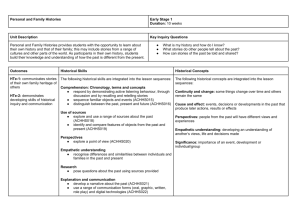

Using Knowledge Vees This is the last in a series of papers on reading and gaining knowledge. In “Rules for Reading”, I discussed how one might go about understanding the reading assignments in technical classes. In “Building Concept Maps”, I defined a concept map as a graphical representation of concepts (the nodes) and the propositions that connect them (the weighted arcs). Concept maps are aids in the learning process. The material in this note comes from [1]. Concepts are a distinct aid to understanding the “local strucuture” of ideas in a technical subject. The final issue is how to integrate these local ideas into a whole. This paper introduces the idea of a knowledge vee. Knowledge: A Quick Review Here are the high points: We divide knowledge into two distinct categories: knowing that and knowing how or explicit and implicit knowledge, respectively. Overarching beliefs are the inherited worldview. These are written about in philosophy texts. Epistemology sets out what one means by the word “truth”. Context is the sum total of ideas inherited through worldview or epistemology. Logical coherence comes from formal structures arising from abstract vocabulary and principles that explain and justify theoretical concepts. Concrete vocabulary is concrete objects and events among concrete events. Abstract vocabulary comes from concepts (generalized objects) and propositions (generalized events). Inherited or grounded concepts and propositions are inherited from previous knowledge and experience. A concept map is a weighed directed, acyclic graph which concepts as nodes and propositions as weights. Knowledge is contextual and consensual. Focus questions set context. The Knowledge Relationship For a general inquiry in science, we can arrange the elements of knowledge in two columns: one for explicit and one for implicit knowledge. The history of any subject in the natural sciences starts at the bottom with objects and events. Constructs and principles are the basis of a theory. At the theory level we pass into the more philosophical aspects of science. What do we claim to know? How do we know it? What is the value of the knowledge? Exercise The discussion probably seems very abstract. A great example of using the knowledge vee is to consider the controversy the theory of evolution. Two of the many possible worldviews are that of the evolutionist and the creationist. The share (I believe) the same objects but differ in the interpretation of the fossil record. How they differ becomes clear by considering the knowledge vee in Table 1. As an exercise, read some articles or books about the controversy and put the information into one of two knowledge vees: one for evolutionists and one for creationists. For more help, see the section “Teaching or Learning with the Knowledge Vee”. Table 1. General Knowledge Vee Conceptual/Theoretical (Explicit) Methodological (Implicit) Focus Question: focus of the inquiry about events/objects World View: General belief Value Claims: Statements system guiding inquiry based on knowledge claims that declare worth of inquiry Philosophy/Epistemology: rules about nature of knowledge and knowing guiding inquiry Theory: General principles that explain why events or objects exhibit observed behavior. Knowledge Claims: Statements answering the focus question and are reasonable interpretations of record. Transformations: Tables, graphs, statistics, etc. Principles: Statements of relationships between concepts that explain events or how objects can be expected to appear or behave. Constructs: Ideas showing specific relationships between concepts without direct origin in events or objects. Concepts: Perceived regularity in events or objects designated by a label Records: Observations of events or objects. Events and/or Objects: Description of the events and/or objects to be studied in order to answer the focus question. Teaching or Learning with the Knowledge Vee 1. Select an event or object that is relatively simple to observe and for which one or more focus questions can readily be identified. Alternatively, a research paper can be used. 2. Begin with a discussion of the event or objects being observed. Be sure that what is identified is the event(s) for which records are made. Sometimes, this is really difficult. 3. Identify and write out the best statement of the focus question(s). Be sure that the focus question(s) relate to the events or objects studied and records to be made. 4. Discuss how the questions serve to focus our attention on the specific features of the events or objects and require that certain kinds of records be obtained if the questions are to be answered. Illustrate how different questions lead to different records. 5. Discuss the source of the questions, or our choice of objects or events to be observed. Help students to see that our relevant concepts, principles or theories guide us in choosing what to observe and what questions to ask. 6. Discuss the validity and reliability of the records. Are the facts (equal to valid, reliable records)? Are there concepts, principles, and theories that relate to our record-making devices that assure their validity and reliability? Are there better ways to gather more valid records? 7. Discuss how we can transform our records to answer our questions. Are there certain graphs, tables, or statistics as useful transformations? 8. Discussion the construction of the knowledge claims. Help students to see that different questions could lead to different records and transformations. The result might be a whole new set of knowledge claims. 9. Discuss value claims. These are values statement such as “X is better than Y” or “X is good”, or we should seek to achieve X. Note that value claims should derive from our knowledge claims, but they are not the same as knowledge claims. 10. Show how concepts, principles, and theories are used to shape our knowledge claims and may influence our value claims. 11. Explore ways to improve a given inquiry by examine which element in the Vee seems to be the weakest link in our chain of reasoning; i.e., in the construction of our knowledge and value claims. 12. Help students see that we operate with a constructivist epistemology to construct claims about how we see the work working, and not an empiricist or positivist epistemology that proves some truth about how the world works. 13. Help students see that a world view is what motivates or guides the investigator in what he or she chooses to try to understand, and controls the energy with which he or she pursues the inquiry. Scientists care about value and pursue better ways to explain rationally how the world works. 14. Compare, contrast, and discuss Vee diagrams made by different students for the same events or objects. Discus how the variety helps to illustrate the constructed nature of knowledge. Bibliography [1] Joseph D. Novak. Learning, Creating, and Using Knowledge: Concept Maps as Facilitative Tools in Schools and Corporations. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers. 1998.