Roman Folkestone - reading activity

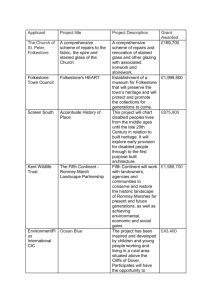

advertisement

Roman Folkestone The Romans invaded Britain in 2 waves, first in 55 BC under the leadership of Julius Caesar and then under the Emperor Claudius in AD 43. Folkestone, with its proximity to the Continent, would have borne the brunt of these invasions and local tribes did all they could to defend their territory. The earthworks at Caesar’s Camp reveal the outline of the hill fort they built on one of the most prominent positions along the hills behind the town. There was probably another hill fort in the areas known as the Bayle. Erosion and subsequent occupation have removed much of this evidence. It is likely that Celts from settlements around Folkestone joined those who massed on the cliffs above Dover to defend their island against the Romans. They put up stiff resistance, throwing javelins, and shooting arrows at the Romans, until the hopeful invaders were forced to move further up the coast to Richborough, where they could land their troops more easily and against less resistance from local tribes. Following the invasion, local tribes would have quickly become used to the site of Roman legions marching along the coastline and setting up villas and military outposts around the area. There is substantial evidence to show that Folkestone was an important trading and military site for the Romans. Evidence of coins and Roman building have been found for generations around the town. The biggest discovery came in the 1920s, when the archaeologists SE Winbolt discovered two enormous Roman villas at East Cliff on the Warren. The villas had over 50 rooms, some of which were decorated with fine Roman mosaics. The site remained open to the public for many years, due to weather, erosion and souvenir hunters it was decided to cover it up again in 1954. The outline of the villa, however, is still visible from above as parched ground over the foundations darkens to reveal the dimensions of the building below. It is quite possible that other buildings were constructed near the villa. In Dover the Romans built a lighthouse or pharos to keep local shipping from crashing into the rocky outcrops below the cliffs and help them safely steer into harbour. The geography of Folkestone is very similar and some historians believe it once stood to the West of the present harbour, but evidence of it has been lost due to land slippages. The villa is in fact two separate buildings. The largest is shaped like the letter ‘E’ and probably would have had two floors, with a total of 56 rooms. In common with Roman architecture at the time, the rooms would have had underfloor heating called hypocaust heating. There is even evidence of a bath in one of the villas. The buildings were faced with locally quarried ragstone. Dating evidence from the finds suggest the site was occupied from AD 100 to AD 350. Finds included Samianware – the most expensive pottery, finely decorated with scenes from Roman life of ancient mythology, and specially imported from abroad. There were coins dating from the Emperor Augustus to the Emperor Maxentius. The largest were from the period of the Christian Emperor Constantine. There were many quern stones – some of which may well have been produced local tribesmen. Archaeologists have found a host of artefacts on the site, which can tell us much about Roman technology and life in the villa. Finds include window glass, iron nails, tools and some bronze and silver objects. In the grounds were remnants of earlier Celtic occupation, including burials urns, coins and bronze and silver ornaments. Some of the tiles for the hypocaust were stamped with the initials CL:BR which suggests there were marines living in the villa serving in the Roman Fleet, the Classis Britannica. Similar tiles have been found at Studfall Castle, the Roman port at Lympne. It is unclear what was the purpose of this settlement. There was a range of hill forts built along the southern coast, including Dover and Lympne, but Folkestone is not listed among them in Roman records. Some historians think that Folkestone way have served as a lookout post or as the site of a beacon which could be used to pass messages along the coast between Dover and Lympne and beyond. Folkestone lacked the deep water anchorages needed for larger Roman trading ships and galleys, so Dover and Lympne remained as important harbours, whilst Folkestone was used to defend the strip of coastline in between. Adapted from Paul Harris, ‘Folkestone a history and celebration’ & C.H. Bishop, ‘Folkestone, the Story of a Town’ Your task Read the article and make a list of the positive changes the Romans would have made to Folkestone. Which changes would local tribes have found most threatening? Imagine you are the owner of the villa at Folkestone. Make a speech to local people emphasising the positive changes Roman occupation will bring. Try to allay some of the fears of local tribes people as well.