English Audio Guide - Folkestone Triennial

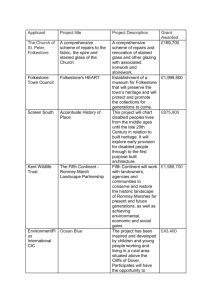

advertisement

Folkestone Triennial 2014 Audio Guide Introduction The lookout is integral to Folkestone's history as a port. A lookout is a structure from which to keep watch - for invasion, for weather, for fish, fortune or friends coming home. A lookout is also the person keeping watch, who can tell us what's coming over the horizon. Either way, a lookout is focused on the future. And in this exhibition, the figure of the lookout stands for the artist – because the artist's act of imagination always involves change, and proposes change. The dynamo of Folkestone's economy in the past has always been the movement of people, whether travellers, or armies going to war or tourists seeking pleasure. Boats, trains and hovercraft have been replaced by the Channel Tunnel (a kind of Folkestone bypass – 2014 will be its 20th anniversary). What comes next? LOOKOUT is an exhibition (outdoors - in the urban environment) that invites you to visit some key points in high places, mainly around the old town of Folkestone, to join artists in questioning what is going on, and see whether you can share a long view on the future. The word 'LOOKOUT' is functional but it's also symbolic. It has a certain psychic weight - it's about expectation: hope and fear. Its warning edge is the point of balance between what we hope we might get, and what we fear might be landed on us. It engages the future of economics, demography and migration, environmentalism and climate change, technology and communication, urban design for social engineering, food security etc Kurt Vonnegut said, “I want to stand as close to the edge as I can without going over. Out on the edge you see all the kinds of things you can't see from the center.” Folkestone’s position at the edge of Britain closest to Eurasia offers unique viewpoints on what's going on in the world today. It's an ideal place to present global issues in a local context. LOOKOUT makes the town the perfect host to these concepts, debates and explorations. Folkestone Triennial 2014 is an invitation to join artists in imagining futures whileexperiencing the present – head in the clouds (or the Cloud), feet on the ground. I would like to encourage all our visitors to immerse themselves in the urban fabric and 'read' it through the eyes of the artists. In a globalised world, these readings will inevitably conjure up all our futures. I hope you find lots to enjoy in the experience. Yoko Ono SKYLADDER and Earth Peace Yoko Ono’s thought-provoking work challenges people’s understanding of art and the world around them. From the beginning of her career, she was a 'conceptualist' whose work encompassed performance, instructions, film, music, and writing. Born in Tokyo in 1933, Ono then moved to New York in 1953, following her studies in philosophy in Japan. By the late 1950s, she was contributing to the cityʼs vibrant contemporary art activities. In 1960 she opened her Chambers Street loft, where she hosted a series of radical performances and exhibited realizations of some of her early conceptual works. By the mid 1960s, her work had become associated with the artistic movement called Fluxus, and in the summer of 1966 she was invited to take part in the Destruction in Art Symposium in London. During this period, she also performed a number of concerts throughout England, which included one at the Metropole Art Centre in Folkestone. In 1969, together with John Lennon, she realized Bed-In, and the worldwide campaign for peace called War Is Over! (if you want it). For Folkestone Triennial 2014, she has contributed two specially composed artworks, SKYLADDER and Earth Peace. SKYLADDER 2014 is an 'instruction' – an invitation to viewers to complete an artwork initiated by the artist. (Her first exhibition of 'instruction paintings' took place in New York in 1961). Sometimes these works are written like a musical score, with the artist taking the place of the composer and the viewer interpreting the score in the way that a musician plays a composition. SKYLADDER 2014 has been written on the wall for everyone to read and enjoy in two of Folkestone's buildings that are generally accessible to the public, the Public Library on Grace Hill and the Quarterhouse in Tontine Street. It doesn't matter who writes it on the wall – like a poem, it's the thought that counts, not the writing. Step ladders have appeared frequently in Ono's work since the mid 1960s as an image of aspiration (climbing higher) and of imagination (taking us nearer the sky, a wonderful open space onto which we can project our desires and dreams). The image of the ladder or stepladder is particularly appropriate for the present exhibition, Lookout, which invites the public to take up different positions around the town in order to imagine the future in different perspectives. Ono's campaign for peace is very important to her as an artist and activist. In 2007, she created a permanent monument to peace, the IMAGINE PEACE TOWER on Viðey Island, Iceland. And In 2011 she was honoured with the prestigious 8th Hiroshima Art Prize for her dedication to peace activism. Her second contribution to Folkestone Triennial 2014 is Earth Peace. This appears on billboards in prominent locations: on a stone slab on the Leas near the Metropole (where she performed in 1966), and is transmitted in Morse Code in a light beam over the Channel towards France. The text is also available as a poster for people to put in their windows to show their support for peace. If you allow your mind to engage with the phrase, it's hard to imagine two tiny words brought together in this way having a greater impact. At the time of the 2008 financial crisis (18 October), Yoko Ono wrote: "If you want to know what your thought processes were like in the past, just examine your body now. And if you want to know what your body will look like in the future, examine your thought processes now. Your body is the scar of your mind." The urban environment of every town is a description of how the people of that town thought and imagined in the past. Strange Cargo The Luckiest Place on Earth Strange Cargo was established in Folkestone in 1995 and operates as a company limited by guarantee and registered charity. Initially focusing on celebratory outdoor arts projects and carnivals, Strange Cargo has developed a reputation for its portfolio of imaginative public and visual arts projects, special celebratory events and programmes with large groups of people. Glance up as you walk under Folkestone Central Railway Bridge and you might be intrigued to see four colourful figures looking down at you. These watchful ‘lookouts’ are Strange Cargo’s idea for Folkestone’s icons of good fortune. Positioned vigilantly on the imposing edifice of the bridge, high above passing pedestrians, each figure is a digitally scanned likeness of a lucky Folkestonian, their luckiness captured in a 3D printed sculpture. Each figure is representative of their age group, stood atop their stone plinth, a fundamental part of The Luckiest Place on Earth. Swathed in symbolic lucky colours; the icons present to onlookers their golden objects of good fortune. Everyone has their own idea of what luck is, it is a universal concept. Strange Cargo invites visitors to pass through this special place and consider what luck means to them. Is it possible that through our own thoughts and actions we can unlock our own luck reserves? Just think what life would be like if we all believed ourselves to be the master of our own good fortune. The symbols held by the statues were suggested hundreds of times over by local people as the most recognisable lucky objects, and they are there to remind us that luck is a universal language. It is these symbols of the horseshoe, wishbone, cat, crossed fingers, four leaf clover, touch wood and lucky mascot that have emerged here as the most identifiable ways to signify good luck. Even the flying seagull, whose random lucky deposits are known to shower down on many a blessed walker, is understood to be a popular seaside bringer of good fortune. By visiting The Luckiest Place on Earth, Strange Cargo suggests it is possible to learn to be lucky. Folkestone is in the throes of being regenerated, but it is its people that have the capacity to make the greatest impact. If we all take the time to spot new opportunities, meet new people and seek out the silver lining, these simple actions can make a big difference to how lucky life appears to be, affecting not just how lucky we feel, but the luck of our town. Take a moment to contemplate what luck means to you, and carry that lucky thought with you throughout your day. Before you leave The Luckiest Place on Earth, don’t miss the opportunity to place a penny in the world’s first Recycling Point for luck and wishes found on the bridge wall. Your wish will mix with the thousands of others, adding to the lucky aura of this place. But the best bit is, that as well as making a wish, you can remove and recycle someone else’s lucky penny. This means you can carry a bit of shared good fortune with you as you go on your way; a reminder that you have visited Folkestone and spent some time at The Luckiest Place on Earth. Diane Dever & Jonathan Wright Pent Houses Dever was born in 1974 in County Mayo, Ireland. Wright was born in 1961 in London, UK. Both live and work in Folkestone. For Folkestone Triennial 2014 they use 5 sculptural installations to invite reflection on the global and growing importance of water in the future. Their work rediscovers the hidden waterways of the Pent Stream, an untapped and unseen resource that flows from the hills to the harbour that was a foundation of Folkestone's past prosperity. Folkestone’s geology is of rift and river valley. The town, in part, owes its existence to many years ago when the watercourse (now called the Pent Stream) broke its way through the hills that surround Folkestone. Bronze Age pottery was found near the banks of the Pent on Folkestone’s golf course located below Junction 13 of the M20. Archeological finds show that by late medieval times Folkestone had grown from around the mouth of the Pent to straddle the banks of the Pent Valley. Early maps show the watercourse as St Eanswythe’s Water. But, by the middle of the18th century, it becomes known as the Pent Stream. The watercourse has been continually re-routed and adjusted over the years to irrigate fields, crops and nurseries before supplying the domestic needs of the old town. Its canalisation brought water to the Bayle and may well be the origin of the myth attributed to St Eanswythe who made water run up hill. It was the powerhouse of the late 18th and 19th century town, supporting three Mills, the Gun Brewery, and the Silver Spring Water Company before supplying the needs of a Tannery in the bottom of the Pent ravine - where Tontine Street meets Dover Road today. At this point, full of filth, its flow reduced such that it stagnated in its lower reaches between Tontine Street and Harbour Street, where again it was filled with waste from houses and inns before flowing out to sea. Pent Houses is a series of 5 stations that reveal the route of the Pent Stream as it travels hidden in concrete tunnels beneath the streets of East Folkestone. The works are reminiscent of New York water towers. They are hybrid objects –part tower, part tank and part shelter and are made of materials not necessarily associated with such structures. The first Pent house marks the outer limits of the town, the site of a long forgotten tower and an early 17th Century chalybeate water spring, said to have health-giving properties. The second marks the tidal reach of the sea and location of the later Pent Bridge. The third Penthouse is on the route of the watercourse that enabled boats to come up Tontine Street. The fourth is nearby an ancient crossing point. And the final, cantilevered structure is where fresh water continuously meets salt water in the Harbour. Their works consider a global ‘lookout’ by focusing on water as a commodity; its scarcity in other lands has caused and will continue to cause friction and war. Global warming may force us to rethink our waste of our water resources. rootoftwo Whithervanes: a Neurotic Early Worrying System rootoftwo is the name of the partnership between American artists John Marshall and Cezanne Charles, who describe themselves as 'hybrid designers'. They combine the skills required for product design with design on a symbolic level, especially in relation to new technology in which much of the design addresses cultural rather than more practical issues. rootoftwo have redesigned weathervanes for the 21st century, and brought these to Folkestone. These are visible on five rooftops around central Folkestone. rootoftwo’s Whithervanes are headless-chicken-shaped weathervanes that are controlled by the climate of fear on the Internet. The five buildings that host the Whithervanes were selected mainly for their height and their distribution within the central area of Folkestone. Because they are also naturally among the more prominent buildings in their neighbourhoods, to some extent they also 'represent' various actual or potential 'communities'. The host buildings are: The Red Cow Public House at the top of Old Foord Road; The Cube (Adult Education College) at the top of Tontine Street; Rocksalt restaurant - overlooking the Harbour; the Martello 3 tower, which looks out over Eastcliff and the Warren; and the Leas Cliff Hall, a music venue sited on The Leas in Folkestone's West End. Whithervanes react to bad news from around the world as journalists to Reuters submit it in real-time. Reuters is an international news agency headquartered in Canary Wharf, London. The level of reaction to the newsfeed is determined by the frequency of the use of keywords. The keywords selected are those that are used for monitoring purposes by the US Department of Homeland Security, as well as words suggested by local residents of Folkestone – words describing conditions that cause concern locally. The degree that the chickens turn away from world news events is determined by the relative threat these pose and their distance from Folkestone. At night, the chickens also illuminate different colours indicating the threat level of events, ranging from low (green), guarded (blue), elevated (yellow), high (orange) to severe (red). The public can interact with the Whithervanes via Twitter to increase or decrease the amount of fear in the system by tweeting using the hashtags: #keepcalm or #skyfalling. With wit, eccentricity and humour the project seeks to undermine and draw attention to the use of fear as an instrument used by the news media on behalf. Jyll Bradley Green/Light (for M. R.) Jyll Bradley was born in Folkestone in 1966, the same year that the Old Gas Works were decommissioned. Since then, the site has been become closed to locals and fallen into disrepair. Her installation created for Folkestone Triennial 2014, Green/Light, is inspired by its story and symbolism as well as by Bradley’s own personal connection to the town. Green/Light (for M. R.) is a major new sculptural light installation by Bradley, which transforms the neglected, historic site of the Old Gas Works in Foord Road North. It was here, in Victorian times, that the first electric light was generated for Folkestone and, for almost a hundred years, the place was a hub of energy and industry. Bradley’s sculpture, designed to catch and reflect the light, is positioned in a south-facing amphitheatre created by the embrace of a remnant red-brick wall of the Gas Works. Her work is positioned precisely on the footprint of one of the gasometers, its form 'remembering' and proposing a different kind of energy in its place – the green energy of growing plants. The sculpture is set out as a hop garden with an inter-connecting field of poles, wirework and twine drawing upon this important part of Kent's historical agriculture. Working with structural engineer Ben Godber, Green/Light (for M. R.) represents a feat of engineering, coupling the centuries’ old technology of hop gardens with the latest in anchorage systems and LED lighting. Green/Light (for M. R.) is an immersive ‘drawing to inhabit’ (to borrow the words of artist Fred Sandback), where visitors are invited to walk through the work, its myriad uprights catching their own reflections and lifting their eyes to the sky and the chalk Downs beyond. As night falls, the work becomes a green beacon for passers by as well as rail commuters travelling home across the adjacent viaduct. Bradley’s installation seeks to connect the beauty of both site and tradition: not as a nostalgic lament, but as a very modern celebration of local industry and energy. As the Old Gas Works awaits development, Green/Light (for M. R.) it creates a space to consider its past, present and future – inviting thoughts about the regeneration of the site for the local community. Marjetica Potrč and Ooze architects The Wind Lift The creators of the Wind Lift, Slovenian artist Marjetica Potrč and Dutch architects, Ooze (Eva Pfannes and Sylvain Hartenberg), have been working together on on-site projects across Europe since 2008. Their laboratory of urban practice is both educational and experimental, inviting residents to participate in creating a new culture of living in public spaces. They use hi-tech knowledge to build low-tech solutions that inspire people to envision cities as built ‘from below’ by the local residents themselves. Visitors are invited to ride the Wind Lift to the top of the Foord Railway Viaduct, where you can enjoy a splendid view of Folkestone’s seafront and the Creative Quarter. The Foord Viaduct, which brought the railway – and prosperity – to Folkestone a hundred and seventy years ago, is the kind of monumental infrastructure project typical of the nineteenth century. By comparison, the Wind Lift is a small enterprise on a human scale. It transforms one of Folkestone’s viaduct arches into a wind funnel. A turbine big enough to fill the upper part of the arch harvests wind energy, which powers the passenger lift. In a sense, we can say it pulls energy from thin air. People take the lift to reach a lookout 25 metres high, where they have a splendid view of the seafront. But the real attraction here is the ride itself. Why? The Wind Lift uses only energy harvested from wind passing through the viaduct and thus creates a closed loop of harvest and use. When enough wind energy is collected, the lift can ascend. But if too little energy has been harvested, the lift will not operate. So the number of rides depends entirely on the strength and volume of the wind in the viaduct. On our visits to Folkestone we asked ourselves what kind of infrastructure project residents would be keen on today. The railway connects Folkestone with the world, but what if we look at the town itself? What about the local connection, the energy harvested right here? When you take the seemingly precarious ride up to enjoy the view out over Folkestone harbour, you put yourself in a position that is totally dependent on the wind. You are directly experiencing the give-and-take relationship between humanity and nature, from a 21st-century lookout on life on earth. The Wind Lift is a small-scale, personal laboratory, where people can get an immediate feeling for humanity’s co-existence with nature. The ‘lookout’ also opens up a view on the new geological age in the earth’s history – the Anthropocene. This is when human activities are having a significant global impact on the earth’s ecosystems – leading to the awareness that we humans are part of nature, not its adversary. When you ride the Wind Lift, you take part in a performative action: you become not only an observer but also a performer who is collaborating with nature. Emma Hart Giving It All That Emma Hart (b. 1974) lives and works in London. She has presented exhibitions and performances both in the UK and internationally. Hart believes that sculpture, most recently ceramics, provides a way to physically corrupt and 'dirty' images in order to forcefully squeeze more life out of them. Her installation for Folkestone Triennial 2014 Giving It All That occupies a two-storey apartment looking out onto Tontine Street. It consists of a series of sculptural works and videos that aim to undermine the power relationship between viewer and artwork. Hart’s radical aesthetic upends and disrupts the viewing process, capturing the confusion, stress and nausea of everyday experience. Hart reflects on feeling under pressure, and how external social forces can push around our fragile internal moods. Set within the domestic interior of a house, the work draws on the hidden anxiety, which inhabits the gap between our public and private selves. The way things look, masks the way things really are. A series of ceramic sculptures requires the viewer to get into various positions. For example, being served or being monitored manufactures different emotional states. Hart has discovered that a tray and a clipboard are essentially the same thing - a small flat surface. However, one is held vertically acting like a shield to conceal private information, whilst the other is held horizontally, reaching out to offer something. Hart serves up outlines of ceramic vessels - empty gestures that have nothing on the inside. Photographic images in the installation, whether moving or still, are fragmented, reflected, multiplied or concealed. Hart says, “The overwhelming real we stumble through is split from the way life is captured on camera. Life looks good in images, or if not good, far away enough for us to manage and control. Photographs can only provide us with a superficial visual reference: they cannot tell us how something really felt.“ For Hart, clay provides a way of working beneath the surface of pictures, and revealing the raw, crude inner state of things that images screen off. 'Giving it all that' is a phrase used to put someone down who is talking excessively and exaggerating. Hart’s sculptures deliver excess through spillages and sweat. Both are physical marks of too much energy bursting through attempts to appear cool. In public settings, both can be embarrassing. In order to eliminate embarrassment, we might need to privately rehearse who we are, and keep ourselves contained. Handily, Hart has provided support; metal structures create an opening for a laptop from which PowerPoint videos enable the viewer to rehearse a presentation of the self. The audio might create a base line of worry, but if we can just keep to the script then we might actually conceal our rising anxiety and doubt. Andy Goldsworthy Clay Window, Clay Steps Born in Cheshire in 1956, Andy Goldsworthy has lived and worked in southwest Scotland for over twenty years. Goldsworthy is interested in how nature and buildings share similar states, and similar fates. He believes that landscapes don’t stop where buildings start – that the forces of erosion and change that occur in landscapes are also at work in towns. As nature degenerates, re-cycles and revives, so do buildings become a part of that powerful moment when things grow out of decay. For Folkestone Triennial 2014 Goldsworthy has made 2 new works, Clay Window and Clay Steps. Both are situated in one of the shops in the Creative Quarter. Clay Window is first encountered from walking down the Old High Street, where a shop window might be mistaken as having been whitewashed or papered over. However, on closer inspection, the surface behind the glass could be a number of things - Stone? Cement? Clay? Plaster? Observers are asked to consider possibilities, and imagine whether the surface might crack in unpredictable ways. Over time, the surface will break into fine black veins that will increasingly allow darkness to cut through from inside. The interior of the shop might at first be in total darkness. But here, the surface will break into piercing white fissures, gradually revealing the light and life from the street, with passing shadows that become silently present in the room. The window surface of Clay Window has been coated in white china clay. This has been chosen for its brilliant translucence and its ability to transform from dense mass to falling fragments. A video of this cracking sequence of the clay can be seen in a nearby location at 64 Tontine Street. This video will record the passing of time, the (economic) tide and the cycle of urban regeneration and decay. Clay Steps is situated in the doorway to the right of Clay Window. In contrast to the clay used in Clay Window, the heavy, grey gault clay of Clay Steps is solid and strong. The stairs have been covered with gault clay, which was collected from local beaches by people living or working in Folkestone. It was refined and mixed by them over several weeks and they assisted in the sculptures’ installation. This direct connection with the local clay and the local community ensures that the energy of the story continues, and the ideas are kept alive. Gault clay once provided widespread employment for Folkestone brick makers, and still attracts fossil collectors from around the world. It is as diverse in its history and rich in its composition as the town of Folkestone itself. Goldsworthy’s use of the different clays - refined white clay and raw gault clay - opens up a further dialogue about the people who have historically inhabited the town. The flat above 48 The Old High Street is now inhabited by plant life – nature taking over. Nature is already invading the derelict building in the Old High Street and the two installations Clay Window and Clay Steps intentionally make visitors think about the progress of nature and how it affects the social nature of the street. Amina Menia Undélaissé – To Reminisce the Future by sharing Bread and Stories Amina Menia was born in 1976 in Algiers, where she still lives and works today. Her work questions the relation between architecture and places with historical significance – questioning and challenging beliefs of the conventional use of spaces through the instrument of the exhibition. Menia is passionate about the margins of a city, what is left over and unexpressed. For Folkestone Triennial 2014, she has specifically chosen an empty, deserted site in the heart of Tontine Street that hides a poignant episode in Folkestone’s history in the First World War. During the war, a bomb fell on this site (situated directly next to the Brewery Tap in Tontine Street), killing and injuring a number of people queuing for food. All that remains today is a small, commemorative plaque that can easily be passed by that retells this event: ‘this tablet marks the place where on May 25th 1917 a bomb was dropped from a German aeroplane killing 60 persons and injuring many others.’ There remains no physical evidence of this fateful tragedy, only an emptiness of remembrance. Menia was moved and drawn to the sobriety of this commemoration and chose to base her artwork on a discreet site-specific intervention aiming to keep the spirit and essence of this ‘fertile emptiness’ alive. A number of differing accounts of this historical event exist. The widespread belief is that the shop was a bakery or grocers called Stokes Brothers. Menia wanted to tap into this urban myth by weaving in some peoples’ personal narratives alongside fragments of politics, geography and immigrant bread recipes. Menia sees bread as a metaphor for separation and gathering. There is nothing more communal that the sharing of bread, which also brings back memories of childhood. Menia spent time meeting and talking to different immigrant families brought together by Folkestone Migrant Support Group. This helped her to explore and understand the mosaic composition of the population of Tontine Street as well as Folkestone’s history. The sharing of different bread recipes was a form of storytelling, uniting the different migrant groups, their different routes to Folkestone and their life stories. It was like opening a family album, revealing symbols and many memories. The recorded sound installation captures and recounts the memories provided by the participants as a response to this project. In addition to acknowledging the centenary commemorations for the First World War, Menia intends to took towards and celebrate the future by means of this intervention that has strong resonance with both Folkestone’s past and present. The title is a mix, or mélange, of French and English words. ‘Délaissé’ in French means ‘derelict’ or ‘deserted’, whereas the English prefix, ‘un’ refers to ‘undoing’ this situation. Therefore, this work aims to create a sharing community that thinks about a common future where this empty space is no longer deserted. Menia hopes that visitors to this site will be inspired both to reminisce about the past but also think about the future though becoming informed about local immigrants’ shared bread recipes and the stories of arrival associated with them. muf architecture/art Payers Park muf architecture/art is a collaborative practice established in 1995 with the specific intention to work in the public realm. The renovation of Payer’s Park creates a ‘Lookout’, an open-air belvedere with views across to the East Folkestone Downs, and yet conversely responds to the Lookout theme as taking counsel, to take care, be mindful and make space for the unknown. Set on a steep, sloping valley the park is set out as a series of open-ended invitations - welcoming visitors to occupy and appropriate structures that allude to what may be real or fictitious relics of the past. Theses relics of the past include: fields of hemp grown along the banks of the Pent Stream that used to provide ropes for passing ships, a place where the yards in which cattle waited in line to be slaughtered and market gardens slowly encroached on by the workshops of the travelling artisans. The design process for Payer’s Park was driven by a series of temporary events with locals in 2013. These included a silent disco, an archaeological dig, an open-air museum, tattooing, bread baking and rapping. These events traced, enacted, and revealed past occupations of the Payer’s Park site as snap shots of the future, and informed the design of a place where more than one thing can happen. A space for difference, and for play, and for uses that are yet unknown. The materials palette and formal language has been developed to point to these past uses of the site, whilst also providing a robust platform for appropriation and future uses. A boardwalk, a plateau, and a number of shortcuts are the main components inviting a number of uses. The boardwalk envelops the site, and acts as a loge, a stage, a site for parkour, and open air gallery. The plateau provides a destination at the centre of the site. The shortcuts connect the boardwalk with the plateau at the centre, providing meeting points, and opportunities for adventurous play, and places for rest. Power is provided to allow events to be held at Payer’s Park, for example by the adjoining Quarterhouse theatre. Seating both formal and informal is provided throughout. The biodiversity of Payer’s Park has been increased through shrub and wild meadow planting. A variety of trees have been planted to complement the existing Sycamore trees, and call attention and frame the park from its various entry points. Roads and parking along the edge of the site have been re-arranged to expand the park further. Street lighting has been re-located away from the edge of the park, with pedestrian-friendly and atmospheric lighting introduced throughout instead. Something & Son Amusefood Something & Son is a London based practice founded by British artists Andrew Merritt and Paul Smyth. Their work is rooted in an inquisitiveness and experimentation and reflects their varied backgrounds and shared passion for art, engineering, social systems, and the environment. Situated on the rooftop of the Glassworks (Folkestone Academy’s sixth form building in the heart of Folkestone town) artists and inventors Something & Son have designed Amusefood. This new rooftop installation mixes innovative green technology with playful, interactive design. The idea for the installation is a reaction to the decline of the English seaside as a holiday destination combined with the experiments from the artists' project FARM:shop in London where food is both grown indoors and then sold on the premises. The installation investigates both the future of food production by growing the ingredients for the British national dish of fish and chips along with the idea of bringing back new kinds of seaside amusements. This was a prominent feature of Folkestone until 2003 when the famous seaside Rotunda was demolished. At first, the structure appears to be a simple polytunnel-style greenhouse. But, as visitors approach the entrance, the facade begins to recall the town's past as a major holiday destination, deceptively resembling a traditional seaside fish and chip shop. However, once inside, there are no deep fat fryers and no tantalising smell of a fish and chip supper. Instead, visitors are confronted with an alternative idea for producing that very same meal. A system of aquaponics fills the polytunnel. This is a closed-loop growth system for fish, chips and minted mushy peas. The fish live in tanks on the floor of the greenhouse. Their nitrogen-rich wastewater is pumped through a series of pipes through vertical hanging columns where the potato, pea and mint plants are growing. The columns allow for maximum crop yield from smaller spaces. This offers an alternative to the customary manner of soil grown plants, which require a great deal of floor space. The plants clean and naturally recycle the water, which is then pumped back into the fish tanks. Unlike traditional greenhouses, the system is automated and requires a minimal amount of effort to look after. As the nights draw in, the greenhouse illuminates with low-energy LED lighting providing essential light for the plants and echoing Folkestone's splendid past as a popular tourist hot spot, glittering with the bright lights of the funfair and amusement arcades. The idea is entirely experimental, but if it works it will create a template for food production that the artists will share freely. So, it can be easily replicated the world over, and can be used as a way for a community with limited space and limited means to produce their own food sustainably. During Folkestone Triennial 2014, the greenhouse will be a focal point for educating people about sustainable methods of food production, engaging local school pupils, residents and visitors from far and wide. Gabriel Lester The Electrified Line (Cross-track Observation-deck) Gabriel Lester was born in 1972 in Amsterdam where he still lives and works. He is an artist and film director who works in a range of media. Performance has always been an important part of his practice, from his youth when he made hip-hop music to more recent constructed environments utilising film, which immerse the audience within the installation. For Folkestone Triennial 2014, Gabriel Lester has constructed a large bamboo structure over the Harbour Railway viaduct. This is a site at the heart of Folkestone’s history as a place of embarkation, and a location from which to look out across the harbour to the open sea. The harbour rail viaduct was opened in 1844 and the line electrified in 1961; but no train has run on it since 2009, and its future remains uncertain. Bamboo is widely used as a strong, easily accessible material for scaffolding in China, where Lester lived and worked for a number of years. Lester’s use of bamboo to build an elevated lookout, on the site of a former wooden watchtower, plays with the geometric shapes created by this organic material. This is in sharp contrast to the brick viaduct, with the remnants of the rail-line visible. Visitors are invited to climb into the installation, to take a new perspective on the future for the harbour area, and the opportunities presented by the elevated position, suggestive of a new pedestrianised gateway to the harbour area. Lester invites the visitor to ‘perform’ within the space, with areas for seating to while away time with friends and lovers, or reading a book with a coffee or shell fish from the local kiosks. Or, to spend a quiet, contemplative time listening to the sea breeze through the bamboo chimes. Lester explains his thought process when creating installations “when you do theatre or music or any other stage-related form of art you can feel the dynamic of the audience you are working with …. Installations function to be an experience. It's something that has a sense of time or has a sense of occurrence. You wander through and it transforms itself as you look. You become aware of something as you engage with it. This is still very much connected with the idea of performance”. Sarah Staton Steve Sarah Staton was born in 1971 in London. She divides her time between Sheffield and London and is a senior lecturer at the Royal College of Art in London Her practice is informed by architecture and design leading to collaborations with architectural studios including muf, who have designed Payers Park for this year’s Triennial. Staton’s work has been included in exhibitions at Tate Modern, The V&A, The Serpentine Gallery and the Crucible Theatre in Sheffield. THE SCHTIP is her most recent collaborative project representing ‘an artist’s space as artwork’ devised with RCA alumni Giles Round. For Folkestone Triennial 2014, Staton spent a year working with an architectural studio and steel fabricators to develop Steve, which she describes as a ‘monument to a person of the future’. Steve is constructed in articulated plates of Corten steel, known as ‘weathering steel’. This type of steel was developed to eliminate the need for painting, and to form a stable rust-like appearance if exposed to the weather for several years. To the casual observer it can look suspiciously unfinished. Despite this, it has many fans in the world of art and architecture and is popularly used in outdoor sculptures, such as Antony Gormley's 'Angel of the North' near Gateshead. It is also widely used in marine transportation. The Stade, where Steve is situated, is still a working area for ships to berth in the harbour, although there are fewer ships than there used to be, and mostly The Stade is given over to leisure and tourism. In recent years, it has hosted a pitch and putt and a bingo hall, both popular leisure activities in traditional English seaside towns. Local fishermen still use the open public space to lay out their nets and happily pass the time of day with locals and tourists alike taking a stroll along the Stade. Steve, and his associated satellite ‘children’ form a new seating area on The Stade inviting passers-by to stop, sit and ‘look out’, at the harbour - or consider their future! Locally grown coastal and edible plants have been planted alongside Steve to contrast with the hard, industrial steel. It is expected that local residents and the Rocksalt restaurant will use them as a food source. Staton has purposely placed a simple, concrete plinth in the middle of Steve, an invitation for you, the visitor, to propose your own ‘monument to the future’. Alex Hartley Vigil Alex Hartley was born in West Byfleet, Surrey in 1963. He is an internationally renowned artist who is known for working with photography and architecture, often incorporating it into both sculpture and installation. Hartley’s work frequently suggests how we might think differently about our constructed surroundings, and how we occupy landscape. Hartley is a keen climber and is interested in looking at alternative ways to use and interact with the built environment. As part of the London 2012 Cultural Olympiad, Alex was selected to create a new work for the South West. His response, Nowhereisland, was a new island he had discovered after it had been revealed from within the melting ice of a retreating glacier. Over its year-long status as a new nation, it accrued over 23,000 citizens, travelled 2,500 miles accompanied by its mobile Embassy and was greeted by thousands in ports and harbours around the south west coast of England. For Folkestone Triennial 2014 Hartley has made a new work, Vigil. His response to the Triennial’s ‘Lookout’ theme is inspired by the prominent and statuesque architecture of the Grand Burstin Hotel. The hotel echoes that of an ocean liner and looks across at the site, which from the 1840s until 2000 was a vibrant and active ferry port and which now sits in stasis awaiting change and development. Standing as it does in the centre of Folkestone and from its topmost rooms, the hotel provides a unique vantage point from which to look out over the sea and back over the town. Five sets of fragile climber’s portaledges are suspended outside the uppermost rooms of the hotel and are inhabited by a lone onlooker, who witnesses everything that passes below. Those carrying out the vigil were drawn from members of the public and the climbing and artistic community. Hartley will be the first and last occupant. At the heart of Vigil is a theme of watchfulness that taps into narratives of removal and isolation, in the main benign but allowing for a darker side, an edge of menace and threat as to what the lookout is watching for, and for whom is he doing the watching. These fragile and dangerous structures refer to the camps of refugees and protestors as well as crow’s nests, lookouts and the isolated retreats of hermits. Hourly recordings document the unfolding events as witnessed by the lone onlookers: weather, sea state, the comings and goings of boats. Human activities will also be considered and noted. Notebooks are kept and the jottings are posted on-line. At night, lights in the tents give the sculptural glow you get from campsites at night. Tim Etchell Is Why the Place Born in 1962, Tim Etchells is a British artist and performance maker based in Sheffield and London. For Folkestone Triennial 2014 his two-part neon sculpture Is Why the Place invites viewers to think about Folkestone’s historical connection to travel and trade - with the everyday processes of arrival and departure which, for many years, moved goods and people via sea, road and railways. Occupying the two platforms of the abandoned Harbour station Etchells work refers both to its specific location and also to Folkestone’s origins and development as a settlement. Etchells work invokes the importance of the harbour for fishing, trade and travel - celebrating Folkestone’s past role as a staging post; a point of transit or passing through for tourists, soldiers, workers, commuters and travellers. The connection is, in short, between place (stability) and movement. Starting as a performance maker, Etchells has developed a practice that is extremely varied – from theatre works to installations, videos and sound compositions as well as novels and short stories. In the evocative setting of the abandoned harbour station, the phrase that makes up his new work is repeated, running in two parallel directions, as if the text is both entering and departing the station. Thus, playfully mirroring the arrival and departure of so many trains, goods and travellers in Folkestone’s past. Since 2008, Etchells neon pieces have been shown all over the world, both in galleries and in relation to landscape or particular contexts. Etchells often uses a line or two of text to colour the way we look, to make a small intervention in the way that we see or think about a particular location. Etchells also explores what we might think of as contradictory aspects of language – relishing the speed, clarity and vividness with which it communicates narrative, image and ideas. But, at the same time, enjoying its amazing capacity to create spaces of reflection, ambiguity and uncertainty for the viewer on encounter, especially in the context of landscape. Installed on the platforms of the now derelict train station at Folkestone Harbour – which was a focal point for war-time shipments and logistics connects the playfully doubled phrase of his work to its immediate surroundings. Thus, his work places it in dialogue with the low-key daily comings and goings of the present time, evoking previous eras of arrival and departure as well as encouraging a focus on the future of Folkestone that is so connected to the processes of human movement and change. Ian Hamilton Finlay Weather is a Third to Place and Time Ian Hamilton Finlay (1925-2006) was one of the greatest British artists active in the second half of the last century. He exercised enormous influence on other artists of his own and subsequent generations. His work is notable for a number of recurring themes including a concern with fishing and the sea, and a continual revisiting of World War II. Both of themes are relate easily to Folkestone. Hamilton Finlay published his first work referencing the sea, The Sea Bed and Other Stories, in 1958. In 1963, Finlay published Rapel, his first collection of concrete poetry (poetry in which the layout and typography of the words contributes to its overall effect). It was as a concrete poet that he first gained wide renown. Much of this work was issued through his own Wild Hawthorn Press. Eventually, he began to compose poems to be inscribed into stone, incorporating these sculptures into the natural environment. Most notably, at his farmhouse Stonypath in the Lanarkshire Hills, also called Little Sparta, and its five-acre garden that he created with his wife Sue Finlay. Since the artist's death in 2006, Little Sparta has been maintained by a Trust. Hamilton Finlay’s work can be seen in many public and private collections around the world. The functioning lighthouse on Folkestone Pier was built and electrified in 1860 and is of a similar design to the tower on Dover's Prince of Wales Pier. The 9 metre high tower, built into the breakwater, can be seen from several points in the town and by walking along the pier from a flight of stairs at the end of the abandoned railway station's platform. The inscription on its inland façade has been commissioned from the estate of Hamilton Finlay. It is one of a number of 'detached sentences' written by Finlay, and has not previously been exhibited. This sentence ‘Weather is a third to a place and time’ honours the importance of the weather to people at sea by adding it as a ‘third' coordinate to the usual ones of place and time. John Harle, Tom Pickard, Luke Menges with the Folkestone Futures Choir Lookout! Folkestone Futures Choir invited people to come together to share their complaints about, and aspirations for, their local town, and to sing them out loud. Based on a ‘complaints choir’ concept conceived by Finnish artists, Tellervo Kalleinen and Oliver Kochta Kalleinen, this project links Folkestone with other cities around the world that adopted this model through complaints choirs of their own. These cities include Birmingham, Edinburgh, Helsinki, St. Petersburg, Hamburg, Chicago, Singapore, Copenhagen and Tokyo. This project with its global associations, links to the Lookout theme of the Triennial and encourages the people of Folkestone to look beyond their local community for inspiration and influence. Folkestone Futures Choir was managed by, and conducted in association with the Sidney De Haan Research Centre for Arts and Health, who have been researching the health and wellbeing impact of singing for older people with chronic health conditions since 2001. Singers from a number of community and health choirs in the area submitted their complaints and aspirations on coloured postcards. These were then sent to the composers, John Harle and Tom Pickard, to craft a brand new piece. The piece they have written is a suite of 5 songs entitled ‘Lookout’ that takes listeners on a journey through the complaints and concerns about the welfare of inhabitants in Folkestone through to an ending that emphasises faith and hope in the future. The 164 singers were recruited from 10 different choirs and included 30 primary school children and around 40 singers who suffer from Parkinson’s disease. Rehearsals took place in May 2014, and a whole day of rehearsals and performances took place on the 29th May at the Leas Cliff Hall in Folkestone. This was captured on film by documentary filmmaker Luke Menges, whose film of the project is on display during Folkestone Triennial 2014. John Harle lives in East Kent and was once described as ‘serving his apprenticeship in the late 20th Century context of expanding horizons and a growing willingness for musicians of all backgrounds to share knowledge’. But, he is also one of its most innovative contributors and seemed the natural choice for the role of composer. Tom Pickard’s words capture the essence of the singer’s observations. But, whilst being necessarily accessible, his eccentric sense of humour, resentment, hope and glory contributed to the appeal of taking part for those that did. It is never easy persuading amateur singers to perform new music, but Harle and Pickard understood that and have delivered something memorable. Pablo Bronstein Beach Hut in the Style of Nicholas Hawksmoor Pablo Bronstein was born in Buenos Aires in 1977 and now works in London. He experiments with a range of media to pursue his interest in architecture, such as drawing, sculpture and installation to performance. He is interested in the ways in which architecture can intervene in personal identity, inform our movements, behaviours, and social customs. Standing ten metres tall, Bronstein’s Beach Hut in the Style of Nicholas Hawksmoor appears like a tall church steeple surrounded by a village of other brightly coloured beach huts on the Folkestone beachfront. Beach Hut in the Style of Nicholas Hawksmoor imagines what a lighthouse might have looked like were it to have been designed by Nicholas Hawksmoor, the early 18th Century Baroque architect, responsible for Spitalfields Church among other landmarks. Hawksmoor (1661-1736) was a British architect who was famous for his church and university architecture, such as Westminster Abbey’s west towers in London. The first lighthouses we would recognise as being similar to our own were 19th century inventions. In the 18th Century the use of the ‘heroic style’, that has come to be defined as quintessentially English, was common along the South East coast because of the defensive nature of the line of ports and castles from Hastings to Dover. This architecture no longer exists in Folkestone. Therefore, Bronstein’s work takes the form of a lighthouse, filling a gap in the town’s history. Beach Hut in the Style of Nicholas Hawksmoor lays spurious claim to being the ‘first’ lighthouse - re-imagining the history of the lighthouse from a hundred years earlier. There is a clear difference between the references used in this ‘monument to architecture’ and its presence as a beach hut in Folkestone. This is to deliberately encourage a sense of folly or of the ridiculous and fantastic, referencing the nature of exotic pleasure architecture in beach towns - the most fantastic and oriental example in the UK being the Brighton Pavilion. Krijn de Koning Dwelling, (for Margate / for Folkestone) Krijn de Koning was born in 1963 in Amsterdam where he still lives and works. He builds labyrinthine architectural structures that invite a dialogue with the environment in which they are placed. His site-specific works – part architecture, part sculpture – challenge the viewer’s understanding, offering new possibilities to navigate and experience the space that the works inhabit. Often brightly coloured and typically constructed using simple materials, his playful structures connect inside and outside spaces and invite direct interaction on the part of the audience. De Koning’s interventions reference the traditions of 20th century art, such as geometric abstraction and Minimalism, but are equally engaged with architecture and 3-dimensional space. Although de Koning has often made work for conventional gallery spaces, he is particularly drawn to ‘ruined’ environments, such as wastelands and abandoned funfairs. Dwelling, (for Margate / for Folkestone) is his first public commission in England, conceived for two locations in Kent: Turner Contemporary in Margate and the zig-zag pathway in Folkestone as part of Folkestone Triennial 2014. Described by de Koning as a ‘dwelling’, it combines a framework of brightly painted wooden beams with a series of voids suggestive of architectural features such as doors, walls and windows to create a space to be walked through, into and around. In Margate, the sculpture is inserted between the external walls of the gallery and the site boundary walls, an area that is used as a walkway for visitors and the general public. De Koning’s interest in this particular area is as an ‘in between’ and somewhat overlooked space on the gallery site where a number of architectural features conjoin and collide in what he has referred to as a ‘strange encounter’. In Folkestone, the second version of the structure is inserted into the network of Victorian caves. It is carved into the zig-zag pathway on the seafront, as though buried within them and only partially visible as a result. De Koning is interested in the impossibility of literally making his work the same in both sites, playing with the notion of repetition and seriality in conceptual art practice. The different characters and uses of the two sites add another layer of interpretation to the works. Both sites attempt to provide some sort of protection or shelter: the fake Victorian caves or grottoes on the one hand, versus the hard-edged contemporary architecture of Turner Contemporary on the other. Both sites lend themselves to this notion of a ‘dwelling’, which in turn plays with the traditional idea of seaside pavilions and beach huts, a common feature of the UK coast. Will Kwan Apparatus #9 (The China Watchers: Oxford University, MI6, HSBC) Will Kwan was born in 1978 in Hong Kong and now lives and works in Toronto, Canada. With this background, it's not surprising that his work as an artist is grounded in social and political awareness, with a keen eye for cultural difference and the power structures encoded in the many forms of culture. Kwan’s art questions the visual and material culture of globalisation – the ironing out of cultural differences by multi-national businesses in favour of a bland diversity in the name of consumer choice. He examines the sociopolitical and cultural consequences of how the ‘global’ is represented visually, and how this affects us all, our sense of taste and aesthetic acceptability no less than our understanding of power structures. Kwan has worked with video, photography, performance and installation while regarding his work as fundamentally sculptural. For Folkestone Triennial 2014, he has created a sculpture for The Vinery. This is a sitting area with fantastic views over the English Channel, perched on the edge of the Leas Cliff. Originally, the Vinery's structure was roofed with glass and it provided shelter for growing grapes, as the name suggests; some vines still grow here. Kwan's sculpture takes the form of three timber screens, their materials and design crafted to fit in with the existing wooden structure. Kwan’s sculpture Apparatus #9 (The China Watchers: Oxford University, MI6, HSBC) picks up the forms of the latticework in the Vinery. In doing so, it plays on the style of a (mainly interior) design called ‘chinoiserie’. This popular Western aesthetic is characterised by motifs and techniques more or less derived from Chinese sources. This style has been present in English architecture, and especially buildings designed for leisure, since the midth 17 Century. The Royal Pavilion in Brighton is perhaps the most famous example. Kwan's screens frame views over the English Channel, a sea route busy with Chinese container vessels plying between the United Kingdom and China, and which still carries a huge volume of traffic. However, the latticework design of the three screens is not purely decorative. While mimicking the effects of 'chinoiserie', each screen is in fact based on an organisational diagram of one of the UK based corporate structures known as 'China Watchers', represented in Kwan's work by the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank, Oxford University and MI6. These bodies continuously monitor any information that has any bearing on China and its relations with other states around the world, reflecting not only the current 'positioning' of China, but also its expected role in the national and international consciousness of the future. Chinoiserie as a motif flattered the taste of the English leisured classes from the 17th to the 20th centuries, at a time that the UK was 'the workshop of the world'. Kwan's sculpture leaves us with the consciousness that in this century, China has taken over this role. And now there are whole quarters of cities in China being built 'in the European style' to provide homes for the new leisured middle classes – estimated to be more numerous than the entire population of Europe.